Highway 3 Corridor Economic Impact Study Draft Final Report October 7, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporting Marks

Lettres d'appellation / Reporting Marks AA Ann Arbor Railroad AALX Advanced Aromatics LP AAMX ACFA Arrendadora de Carros de Ferrocarril S.A. AAPV American Association of Private RR Car Owners Inc. AAR Association of American Railroads AATX Ampacet Corporation AB Akron and Barberton Cluster Railway Company ABB Akron and Barberton Belt Railroad Company ABBX Abbott Labs ABIX Anheuser-Busch Incorporated ABL Alameda Belt Line ABOX TTX Company ABRX AB Rail Investments Incorporated ABWX Asea Brown Boveri Incorporated AC Algoma Central Railway Incorporated ACAX Honeywell International Incorporated ACBL American Commercial Barge Lines ACCX Consolidation Coal Company ACDX Honeywell International Incorporated ACEX Ace Cogeneration Company ACFX General Electric Rail Services Corporation ACGX Suburban Propane LP ACHX American Cyanamid Company ACIS Algoma Central Railway Incorporated ACIX Great Lakes Chemical Corporation ACJR Ashtabula Carson Jefferson Railroad Company ACJU American Coastal Lines Joint Venture Incorporated ACL CSX Transportation Incorporated ACLU Atlantic Container Line Limited ACLX American Car Line Company ACMX Voith Hydro Incorporated ACNU AKZO Chemie B V ACOU Associated Octel Company Limited ACPX Amoco Oil Company ACPZ American Concrete Products Company ACRX American Chrome and Chemicals Incorporated ACSU Atlantic Cargo Services AB ACSX Honeywell International Incorporated ACSZ American Carrier Equipment ACTU Associated Container Transport (Australia) Limited ACTX Honeywell International Incorporated ACUU Acugreen Limited ACWR -

March 2007 News.Pub

WCRA NEWS MARCH 2007 AGM FEB. 27, 2007 WESTERN RAILS SHOW MARCH 18, 2007 WCRA News, Page 2 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING NOTICE Notice is given that the Annual General Meeting of the West Coast Railway Association will be held on Tuesday, February 27 at 1930 hours at Rainbow Creek Station. The February General Meeting of the WCRA will be held at Rainbow Creek Station in Confederation Park in Burnaby following the AGM. ON THE COVER Drake Street Roundhouse, Vancouver—taken November 1981 by Micah Gampe, and donated to the 374 Pavilion by Roundhouse Dental. Visible from left to right are British Columbia power car Prince George, Steam locomotive #1077 Herb Hawkins, Royal Hudson #2860’s tender, and CP Rail S-2 #7042 coming onto the turntable. In 1981, the roundhouse will soon be vacated by the railway, and the Provincial collection will move to BC Rail at North Vancouver. The Roundhouse will become a feature pavilion at Expo 86, and then be developed into today’s Roundhouse Community Centre and 374 Pavilion. Thanks to Len Brown for facilitating the donation of the picture to the Pavilion. MARCH CALENDAR • West Coast Railway Heritage Park Open daily 1000 through 1700k • Wednesday, March 7—deadline for items for the April 2007 WCRA News • Saturday, March 17 through Sunday, March 25—Spring Break Week celebrations at the Heritage Park, 1000—1700 daily • Tuesday, March 20—Tours Committee Meeting • Tuesday, March 27, 2007—WCRA General Meeting, Rainbow Creek Station in Confederation Park, Burnaby, 1930 hours. The West Coast Railway Association is an historical group dedicated to the preservation of British Columbia railway history. -

Contract Specialist Teck Resources Ltd – Sparwood Shared Services, Sparwood, BC Posting Date: July 23, 2021

Teck Coal Limited Recruiting Centre RR #1, Highway #3 +1 250 425 8800 Tel Sparwood, B.C. Canada V0B 2G0 www.teck.com Job Opportunity Contract Specialist Teck Resources Ltd – Sparwood Shared Services, Sparwood, BC Posting Date: July 23, 2021 Closing Date: August 22, 2021 Reporting to the Purchasing Supervisor, the Contract Specialist, (known at Teck as the Purchasing Agent) is responsible for acquiring the best total value in the acquisition of materials and services to meet ongoing needs and support initiatives. To be successful, we are looking for someone capable of working under minimal direction and who functions best in a high-performance atmosphere; someone who has strong interpersonal and communication skills, who can mentor others. Excellent negotiating, problem-solving, and decision-making skills are vital. You will have the opportunity to implement procedural improvements to streamline business practices and be instrumental in the successful execution of contracts. You will also have the ability to interact with both operations and support and contract groups throughout our company, gaining knowledge of our mining business. Join us in the breathtaking Elk Valley of British Columbia. Here you will find outdoor adventure at your fingertips. Whether it's biking and skiing, or the laid- back atmosphere of fishing and hiking, there is something for everyone! With an attractive salary, benefits, and Earned Day Off schedule, come experience what work life balance is all about! Responsibilities: • Be a courageous safety leader, adhere -

Convention 2012 News in This Issue!

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association APRIL 2012 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers Watching TV Outside on a Rare Warm Evening in March SEE SOME REALLY NICE CENTRAL AMERICAN DX PHOTOS IN THIS MONTH’S PHOTO NEWS MORE CONVENTION 2012 NEWS Visit Us At www.wtfda.org IN THIS ISSUE! THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info _______________________________________________________________________________________ Welcome to the April VUD! It seems that summer has kicked into gear in many parts of North America a little early. The grass is turning green, the trees are beginning to bud and the snow shovels are put away for the season. There’s been a little bit of tropo. There’s been a little bit of skip in the south. There’s also been some horrible storms and tornados in places. We hope everyone is okay and stayed out of danger. This month we find that Ken Simon (Lake Worthless, FL) has rejoined the club. -

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia

Indigenous Experiences Guide to British Columbia Immerse yourself in the living Traditions Indigenous travel experiences have the power to move you. To help you feel connected to something bigger than yourself. To leave you changed forever, through cultural exploration and learning. Let your true nature run free and be forever transformed by the stories and songs from the world’s most diverse assembly of living Indigenous cultures. #IndigenousBC | IndigenousBC.com Places To Go CARIBOO CHILCOTIN COAST KOOTENAY ROCKIES NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TRADITIONAL LANGUAGES: TŜILHQOT’IN | TSE’KHENE | DANE-ZAA | ST̓ÁT̓IMCETS KTUNAXA | SECWEPEMCSTIN | NSYILXCƏN SM̓ALGYA̱X | NISG̱A’A | GITSENIMX̱ | DALKEH | WITSUWIT’EN SECWEPEMCSTIN | NŁEʔKEPMXCÍN | NSYILXCƏN | NUXALK NEDUT’EN | DANEZĀGÉ’ | TĀŁTĀN | DENE K’E | X̱AAYDA KIL The Ktunaxa have inhabited the rugged area around X̱AAD KIL The fjordic coast town of Bella Coola, where the Pacific the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers on the west side of Ocean meets mighty rainforests and unmatched Canada’s Rockies for more than 10 000 years. Visitors Many distinct Indigenous people, including the Nisga’a, wildlife viewing opportunities, is home to the Nuxalk to the snowy mountains of Creston and Cranbrook Haida and the Tahltan, occupy the unique landscapes of people and the region’s easternmost point. The continue to seek the adventure this dramatic landscape Northern BC. Indigenous people co-manage and protect Cariboo Chilcotin Coast spans the lower middle of offers. Experience traditional rejuvenation: soak in hot this untamed expanse–more than half of the size of the BC and continues toward mountainous Tsilhqot’in mineral waters, view Bighorn Sheep, and traverse five province–with a world-class system of parks and reserves Territory, where wild horses run. -

2016 Kettle Valley Express Adventure Travel Guide Is We Could Bring It to Life

Hope: Embrace the Journey.............................................................................2 Princeton Welcomes the Adventurer in You!...................................................3 Okanagan Similkameen Click Hike & Bike™ ..............................................4 Escape to Osoyoos................................................................................................5 Penticton & Wine Country, Take Time to Breathe.......................................6, 7 Okanagan Cycle Tourism...................................................................................8 Thompson Okanagan Remarkable Experience...........................................9 Discover Naramata............................................................................................10 Historic Myra Canyon.......................................................................................11 Boundary Country Wanderlust and Golden Dreams........................12, 13 CONCEPT/ PRODUCTION/ ADVERTISING SALES ....................................................................................................14 LAYOUT/DESIGN/EDITOR MANAGER West Boundary Brian McAndrew: Publisher Lisa Cartwright Ahhhh Fishing......................................................................................................15 [email protected] [email protected] Floating Your Cares Away...............................................................................16 It is with great appreciation to all our advertisers, contributors and Midway -

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity in the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity May 2010 Prepared with the: support of: Galvin Family Fund Kayak Foundation HIGHWAY 3: TRANSPORTATION MITIGATION FOR WILDLIFE AND CONNECTIVITY IN THE CROWN OF THE CONTINENT ECOSYSTEM Final Report May 2010 Prepared by: Anthony Clevenger, PhD Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University Clayton Apps, PhD, Aspen Wildlife Research Tracy Lee, MSc, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Mike Quinn, PhD, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Dale Paton, Graduate Student, University of Calgary Dave Poulton, LLB, LLM, Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative Robert Ament, M Sc, Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .....................................................................................................................................................iv List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................................v Executive Summary .........................................................................................................................................vi Introduction........................................................................................................................................................1 Background........................................................................................................................................................3 -

Avalanche Information for Subscribers

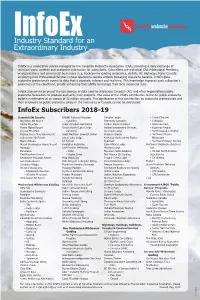

InfoEx Industry Standard for an Extraordinary Industry InfoEx is a cooperative service managed by the Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA), providing a daily exchange of technical snow, weather and avalanche information for subscribers. Subscribers are individual CAA Professional Members, or organizations and commercial businesses (e.g. backcountry guiding companies, ski hills, BC Highways, Parks Canada) employing CAA Professional Members whose operations require actively managing avalanche hazards. InfoEx gives avalanche professionals access to data that is accurate, relevant and real time. This knowledge improves each subscriber’s awareness of the conditions, greatly enhancing their ability to manage their local avalanche risks. InfoEx also serves as one of the key sources of data used by Avalanche Canada’s (AC) and other organizations public avalanche forecasters to produce and verify their products. The value of the InfoEx contribution to the AC public avalanche bulletin is estimated at an excess of $2 million annually. The significance of this contribution by avalanche professionals and their employers to public avalanche safety in the mountains of Canada cannot be overstated. InfoEx Subscribers 2018-19 Downhill Ski Resorts KPOW! Fortress Mountain Dezaiko Lodge • Coast/Chilcotin Big White Ski Resort Catskiing Extremely Canadian • Columbia Castle Mountain Great Canadian Heli-Skiing Golden Alpine Holidays • Kootenay Pass Fernie Alpine Resort Gostlin Keefer Lake Lodge Hyland Backcountry Services • Kootenay Region Grouse Mountain Catskiing Ice Creek Lodge • North Cascades District Kicking Horse Mountain Resort Great Northern Snowcat Skiing Kokanee Glacier • Northwest Region Lake Louise Ski Resort Island Lake Lodge Kootenay Backcountry Guides Ningunsaw Marmot Basin K3 Cat Ski Kyle Rast • Northwest Region Terrace Mount Washington Alpine Resort Kingfisher Heliskiing Lake O’Hara Lodge Northwest Avalanche Solutions Norquay Last Frontier Heliskiing Mistaya Lodge Ltd. -

Ski Resorts (Canada)

SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] ALBERTA • WinSport's Canada Olympic Park (1988 Winter Olympics • Canmore Nordic Centre (1988 Winter Olympics) • Canyon Ski Area - Red Deer • Castle Mountain Resort - Pincher Creek • Drumheller Valley Ski Club • Eastlink Park - Whitecourt, Alberta • Edmonton Ski Club • Fairview Ski Hill - Fairview • Fortress Mountain Resort - Kananaskis Country, Alberta between Calgary and Banff • Hidden Valley Ski Area - near Medicine Hat, located in the Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park in south-eastern Alberta • Innisfail Ski Hill - in Innisfail • Kinosoo Ridge Ski Resort - Cold Lake • Lake Louise Mountain Resort - Lake Louise in Banff National Park • Little Smokey Ski Area - Falher, Alberta • Marmot Basin - Jasper • Misery Mountain, Alberta - Peace River • Mount Norquay ski resort - Banff • Nakiska (1988 Winter Olympics) • Nitehawk Ski Area - Grande Prairie • Pass Powderkeg - Blairmore • Rabbit Hill Snow Resort - Leduc • Silver Summit - Edson • Snow Valley Ski Club - city of Edmonton • Sunridge Ski Area - city of Edmonton • Sunshine Village - Banff • Tawatinaw Valley Ski Club - Tawatinaw, Alberta • Valley Ski Club - Alliance, Alberta • Vista Ridge - in Fort McMurray • Whispering Pines ski resort - Worsley British Columbia Page 1 of 8 SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] • HELI SKIING OPERATORS: • Bearpaw Heli • Bella Coola Heli Sports[2] • CMH Heli-Skiing & Summer Adventures[3] • Crescent Spur Heli[4] • Eagle Pass Heli[5] • Great Canadian Heliskiing[6] • James Orr Heliski[7] • Kingfisher Heli[8] • Last Frontier Heliskiing[9] • Mica Heliskiing Guides[10] • Mike Wiegele Helicopter Skiing[11] • Northern Escape Heli-skiing[12] • Powder Mountain Whistler • Purcell Heli[13] • RK Heliski[14] • Selkirk Tangiers Heli[15] • Silvertip Lodge Heli[16] • Skeena Heli[17] • Snowwater Heli[18] • Stellar Heliskiing[19] • Tyax Lodge & Heliskiing [20] • Whistler Heli[21] • White Wilderness Heli[22] • Apex Mountain Resort, Penticton • Bear Mountain Ski Hill, Dawson Creek • Big Bam Ski Hill, Fort St. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Community Profile: New Denver,British Columbia

C OMMUNITY PROFILE: NEW DENVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA FALL 2015 The Columbia Basin Rural Development Institute, at Selkirk College, is a regional research centre with a mandate to support informed decision-making by Columbia Basin-Boundary communities through the provision of information, applied research and related outreach and extension support. Visit www.cbrdi.ca for more information. CONTENTS LOCATION...................................................................................................................................................... 1 New Denver - British Columbia ................................................................................................................. 1 Distance to Major Cities ............................................................................................................................ 1 Coordinates, Elevation and Area .............................................................................................................. 2 New Denver Municipal Website ............................................................................................................... 2 DEMOGRAPHICS............................................................................................................................................ 2 Population Estimates 2014 ....................................................................................................................... 2 Age Characteristics 2011 .......................................................................................................................... -

Nhmbbk 4. Ainswoeth, British Columbia, Ootobeb 3, 1891

^p NHMBBK 4. AINSWOETH, BRITISH COLUMBIA, OOTOBEB 3, 1891. TEU CBHT& PAVOK& THE PRKR ADMISSION OP OUR ORES. Blue Bell and Kootenay Chief on the east side WILD OVER A K12W DISCOVERY. of the lake and a score or two on the west side— The free admission into the United States of are practically-dry ore propositions, and produce The reports circulated and stories told by Jack the lead ores of British Columbia is a question just the ores \hat are needed on this side, of the Sea ton, the Henuessy boys, Prank Flint, and that is receiving considerable attention, both in line to making smelting a success. Nearly all John McGuygan on their return from the this section and in the neighboring sections to the lead claims in Hot Springs district are owned Kaslo-Slocan divide, on Thursday, set the town by Americans, and the wages paid miners and of Ainsworth wild with excitement. Even G. the* south of the boundary line. The people of other employes ai-e the same as paid in Montana B. Wright felt as if he was young enough to Spokane generally favor the admission, while and Idaho. pack his blankets over the range to the new find. those of iho Occur d'Alenes are in opposition. "Were the lead ores of British Columbia Bill Hennessy, who has bar) considerable-ex allowed to flow into the United States as freely perience both as a miner and a prospector in The following are the opinions of a well-known as the waters^pf the Columbia river, it would not Spokane, business man, and are copied from the detract one particle from the income of a single Colorado, says the croppings are fully as large Chronicle of Sept cm her 30th: Cceur d'Alene mine owner.