The Labasa Strike, 1907

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WIF27 09 Vuki.Pdf

SPC • Women in Fisheries Information Bulletin #27 9 Changing patterns in household membership, changing economic activities and roles of men and women in Matokana Village, Onoilau, Fiji Veikila Vuki1 Introduction Vanua The Ono-i-Lau group of islands is located Levu EXPLORING in the southern section of the Lau archi- MAMANUCA I-RA-GROUP ISLES pelago in the east of Fiji at 20˚ 40’ S and Koro Sea 178˚ 44’ W (Figure 1). MAMANUCA Waya I-CAKE-GROUP LAU GROUP The lagoons, coral reefs and islands of the Viti Ono-i-Lau group of islands are shown in Levu Figure 2. There are over one hundred islands in the Ono-i-Lau group, covering a total land area of 7.9 km2 within a reef system of 80 km2 MOALA (Ferry and Lewis 1993; Vuki et al. 1992). The GROUP two main islands – Onolevu and Doi – are inhabited. The three villages of Nukuni, South Pacific Ocean Lovoni and Matokana are located on Onolevu Island, while Doi village is located on Doi Island. A FIJI The islands of Onolevu, Doi and Davura are volcanic in origin and are part of the rim of A• Map of Fiji showing the location a breached crater. Onolevu Island is the prin- of Ono-i-Lau cipal island. It is an elbow-shaped island with two hills. B• Satellite map of Ono-i-Lau group of islands showing the main Tuvanaicolo and Tuvanaira Islands are island of Onolevu where located a few kilometres away from the the airstrip is located and Doi islands of Onolevu but are also part of the Island, the second largest island in Ono-i-Lau group. -

Suva/Nadi/Nausori/Labasa Reporting To: Team Leader Fleet Objectives

JOB DESCRIPTION Position: Driver Location of position: Suva/Nadi/Nausori/Labasa Reporting to: Team Leader Fleet Objectives: Provide full-time driving and administration support to all staff. Duties and Responsibilities: Drive vehicle for official travel and business, or as requested by head driver • Maintain high standard of customer service to both internal and external guests. • Ensure punctuality and safe transporting of all staff to their respective destinations • Observing the road and traffic laws and regulations and ensures that safe driving practices are adhered to • Conducts weekly inspection of company fleet and ensures the vehicles at all times has a current warrant of fitness and arranges for vehicle fitness renewal Ensures vehicle is given regular/day-to-day maintenance checks: check oil, water, battery, brakes, tyres, etc. Conduct minor repairs eg replace bulbs, change tyres etc. Report defects to head Team Leader Fleet promptly and ensures that vehicles are serviced regularly • Ensures all FRA vehicles is secured at all times • Assist the Team Leader Fleet to ensure vehicle insurance and registration is updated according to schedule • Maintain a Log of all trips, daily mileage, oil changes, etc; • Assists in Photocopying, filing, handling mail, delivering goods and correspondences, carrying parcels, packages, and delivery and collection of official documents as per required • Provides assistant to the Admin team in the time working at the office 1 • Ensures safety of passengers • Require to travel outside working hours • Other duties assigned by Line Manager as and when require • Arrange FRA fleet service • Assist technical staff and inspectors in field work • Attend to vehicle breakdowns • Assist in purchasing and banking • Assist in vehicle allocation • Arrange registration renewals • Deliveries of Board Paters and Contract documents for signing. -

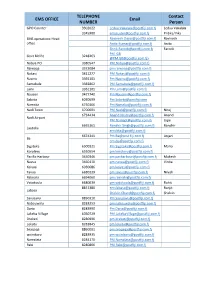

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Nausori Town Council Has Limited Assets Confined Mainly to the Bus Suva Or Elsewhere

1.0BACKGROUND OF NAUSORI TOWN 1.1 Introduction Nausori is a town that has evolved from what was once a thriving sugar industry in the 19th century for the colony of Fiji, to a rural backwater town on the banks of the Rewa from 1937 onwards to the present. It is historic in the sense that it was the first sugar mill established by the Colonial Sugar Refining Co of Australia in 1881. It also hosted the first major influx of Indian labourers in Viti Levu in 1881 to come and work on the sugar plantations in the Rewa Delta. The descendants of those labourers have remained in Nausori an or have moved to other parts of the country. A lot of the relic of Nausori’s colonial past still stand today as a postmark of what was once Nausori’s golden age between 1881 – 1959. It ceased operations in early 1960’s and the company and its workers left with a town in limbo. A distinct physical character of the town in the 1960’s was the abundance of open spaces for sporting and cultural activities. Over the years these have become eroded by the conversion of some of those spaces into development lots where buildings have begun to establish themselves undermining the order and coherence that once marked the old town. Nausori has grown rapidly in the last few years because of the addition of the Naulu/Nakasi and Davuilevu Housing areas. In the 1996 census the town’s population was 17,000. By 2007 the population was 24,950. -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

Great Sea Reef

A Living Icon Insured Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it Fiji’s Great Sea Reef Foreword Fiji’s Great Sea Reef (GSR), locally known as ‘Cakaulevu’ or ‘Bai Kei Viti’, remain one of the most productive and biologically diverse reef systems in the Southern Hemisphere. But despite its uniqueness and diversity it remains the most used with its social, cultural, economic and environmental value largely ignored. A Living Icon Insured Stretching for over 200km from the north eastern tip of Udu point in Vanua Levu to Bua at the north- Sustain-web of life creating it-livelihoods woven in it west edge of Vanua Levu, across the Vatu-i-ra passage, veering off along the way, to hug the coastline of Ra and Ba provinces and fusing into the Yasawa Islands, the Great Sea Reef snakes its way across the Fiji’s Great Sea Reef western sections of Fiji’s ocean. Also referred to as Fiji’s Seafood Basket, the reef feeds up to 80 percent of Fiji’s population.There are estimates that the reef system contributes between FJD 12-16 million annually to Fiji’s economy through the inshore fisheries sector, a conservative value. The stories in this book encapsulates the rich tapestry of interdependence between individuals and communities with the GSR, against the rising tide of challenges brought on by climate change through ocean warming and acidification, coral bleaching, sea level rise, and man-made challenges of pollution, overfishing and loss of habitat in the face of economic development. But all is not lost as communities and individuals are strengthened through sheer determination to apply their traditional knowledge, further strengthened by science and research to safeguard and protect the natural resource that is home and livelihood. -

Identified Gaps & Proposed Solutions & Logistics Planning

FIJI LOGISTICS PLANNING OVERVIEW Identified Gaps & proposed Solutions & Logistics Planning GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP PROGRAM FUNDED BY: 1 | P a g e A. LOGISTICS PLANNING OVERVIEW a. IDENTIFIED GAPS & PROPOSED SOLUTIONS Organizing emergency logistics operations for delivery and distribution may be a real challenge in Fiji due to the remoteness of outer Islands, access conditions to affected locations on the main Islands and operational constraints in entry ports facilties. All actors agree that logistics is one of the major bottlenecks in past emergency responses. On the whole, both logistics infrastructures and services are in place in Fiji. Technical agencies in charge of those infrastructures and services are dedicated and competent. Emergency Logistics operations are generally organized, efficient and adequate. Nevertheless, some areas of improvement have been identified. These areas are detailed here under together with propositions to address those gaps. A separate “Logistics Preparedness Plan” has been drafted to implement those propositions of improvement. LOGISTICS RELATED GAPS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: The logistics gaps identified concern the following subjects: o Coordination & Preparedness o Networking o Human Resources o Capitalization o Information Management o Storage o Commodities tracking o Operational and access challenges Coordination & Preparedness Cyclones / Floods seasons need to be prepared, also regarding logistics issues. The logistics coordination needs to meet before the wet season to prepare for potential emergencies, revise everybody’s roles and responsibilities, etc. Stand-by agreements / protocols could be established and agreed upon prior to emergencies with key emergency actors, including customs, RFMF, Police, private companies, etc. Formalize transport options ahead of the cyclone season. Sectors concerned are: customs, transport (land, sea, and air), and storage, dispatching and tracking. -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Ministry of Employment, Productivity & Industrial Relations NATIONAL

Ministry of Employment, Productivity & Industrial Relations NATIONAL OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY SERVICE PUBLIC NOTICE BUSINESS LICENSE - OHS COMPLIANCE INSPECTION HEALTH AND SAFETY AT WORK ACT 1996 The National Occupational Health and Safety Service of the Ministry of Employment, Productivity and Industrial Relations is required under the Health and Safety at Work Act (HASAWA) 1996 to ensure health and safety compliance of workplaces in Fiji. In ensuring this, the National OHS Service would like to inform all business owners and occupiers of workplaces that the conduct of OHS compliance inspection for the renewal of existing business license for the year 2020 will commence from Monday, 14th October till Tuesday, 31st December 2019. The OHS inspection of workplaces for the issuance of new business licences will be conducted as and when required. The relevant general workplace inspection application forms can be accessed on the Ministry’s website: www.employment.gov.fj. The documentations required for submission with the application form are copies of: a. National Fire Authority (NFA) Certificate / Report b. Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Policy c. Emergency Evacuation Plan For further information please contact the following: CENTRAL / EASTERN DIVISION Lautoka Office NORTHERN DIVISION Suva Office Level 1, Tavaiqia House Labasa Office Level 6, Civic House Tavewa Avenue, Lautoka Level 2, Ratu Raobe Building Townhall Road, Suva Phone: (679) 6660 305 / 9907 343 Jaduram Street, Labasa Phone: (679) 3316 999 / Contact Person – Osea -

Fiji, Macuata Province Learning Site

Macuata Province Learning Site MACBIO Introductory Field Visit to the Mali District MACBIO | | September 12, 2016 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Objectives .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Methods ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Findings ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Interviews ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Success Stories .................................................................................................................................... 9 WWF ................................................................................................................................................ 9 Strong Leadership ........................................................................................................................... 9 Strong Sense of Ownership ........................................................................................................... 10 Tabu Surveillance ......................................................................................................................... -

TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall

Pacific Islands - Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 125 Country Name: Fiji TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall Station (include data period) January 2018 November December Total 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking 2017 2017 Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall Total Total (mm) (mm) (mm) Western Division Penang Mill 187.2 134.1 393.6 228.6 388.4 296.4 73/109 (1910-2017) Lautoka Mill (1900- 131.0 187.3 268.7 172.2 364.6 258.5 79/118 2017) Nadi Airport 138.8 202.4 335.2 220.1 354.7 298.5 50/77 (1942-2017) Viwa - 88.6 191.0 105.6 312.7 206.2 17/37 (1978 -2017) Central Division Laucala Bay (Suva) 661.5 411.3 265.2 252.6 378.5 311.2 31/77 (1942-2017) Nausori Airport 487.4 340.7 413.8 261.0 383.6 312.5 46/62 (1957-2017) Tokotoko (Navua) 871.5 347.9 355.9 273.9 412.5 342.8 38/73 (1945-2017) Eastern Division Lakeba 381.5 114.2 152.3 173.0 305.8 242.2 19/68 (1950-2017) Vunisea (Kadavu) 555.6 172.4 167.7 167.6 280.8 227.8 29/83 (1931-2017) Ono-i-Lau 174.6 124.0 272.9 124.3 223.0 180.0 57/71 (1943-2017) Northern Division Labasa Airport 267.1 213.0 166.8 242.2 464.2 382.3 12/61 (1946-2017) Savusavu Airfield 235.5 197.2 157.7 204.8 319.0 254.1 16/59 (1956-2017) Rotuma 369.3 192.0 267.0 286.3 409.2 336.9 33/106 (1912-2017) Period: *below normal/normal/above normal M - Missing TABLE 2: Three-monthly Rainfall November 2017 to January 2018 Predictors and Period used: NINO3.4 SST Anomalies: August to September 2017 Station Three- 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking Forecast probs.* Verification* month Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall (include LEPS) (Consistent, Total (mm) (mm) (mm)