Edgar G. Ulmer's Film the Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

HUNGARIAN STUDIES 14. No. 2. (2000)

BELA LUGOSI - EIN LIEBHABER, EIN DILETTANT HARUN MAYE Universität zu Köln, Köln, Deutschland I. „I am Dracula". So lautete der erste Satz, den ein Vampir in einem amerikani schen Tonfilm sagen mußte, und der auch seinen Darsteller unsterblich machen sollte. Bei dem Namen Dracula bedürfen wir weder der Anschauung noch auch selbst des Bildes, sondern der Name, indem wir ihn verstehen, ist die bildlose einfache Vorstellung einer Urszene, die 1897 zum ersten Mal als Roman erschie nen, und dank dem Medienverbund zwischen Phonograph, Schreibmaschine, Hypnose, Stenographie und der Sekretärin Mina Harker schon im Roman selbst technisch reproduzierbar geworden ist.1 Aber ausgerechnet über ein Medium, das im Roman nicht erwähnt wird, sollte Draculas Wiederauferstehung seitdem Nacht für Nacht laufen. Weil Vampire und Gespenster Wiedergänger sind, und im Gegensatz zu Bü chern und ihren Autoren bekanntlich nicht sterben können, müssen sie sich neue Körper und Medien suchen, in die sie fahren können. Der Journalist Abraham Stoker hat den Nachruhm und die Wertschätzung seines Namens zusammen mit dem Medium eingebüßt, das ihn berühmt gemacht hatte, nur damit fortan der Name seines schattenlosen Titelhelden für immer als belichteter Schatten über Kinoleinwände geistern konnte. Aber Spielfilme kennen so wenig originale Schöpfersubjekte wie Individuen. Dracula ist eben bloß ein Name, und als solcher ein „individuelles Allgemeines" wie die Bezeichnung der Goethezeit, jener Epo che und Dichtungskonzeption, der auch Dracula poetologisch noch angehörte, für sogenannte Individuen und Phantome gleichermaßen lautete. Es ist in diesem Namen, daß wir Bela Lugosi denken.2 IL Seit Tod Brownings Dracula von 1931 braucht dieser Name um vorstellbar zu sein, nicht mehr verstanden werden, weil er selbst angefangen hatte, sich vorzu stellen. -

Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9

RIVERCREST PREPARATORY ONLINE SCHOOL S P E C I A L I T E M S O F The River Current INTEREST VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 DECEMBER 16, 2014 We had our picture day on Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9. If you missed it, there will be another opportunity in the spring. Boris Karloff, the voice of the narrator and the Grinch in the Reserve your cartoon, was a famous actor yearbook. known for his roles in horror films. In fact, the image most of us hold in our minds of Franken- stein’s monster is actually Boris Karloff in full make up. Boris Karloff Jan. 12th – Who doesn’t love the Grinch Winter Break is Is the reason the Grinch is so despite his grinchy ways? The Dec. 19th popular because the characters animated classic, first shown in are lovable? We can’t help but 1966, has remained popular with All class work must adore Max, the unwilling helper of children and adults. be completed by the Grinch. Little Cindy Lou Who The story, written by Dr. Seuss, the 18th! is so sweet when she questions was published in 1957. At that the Grinch’s actions. But when the I N S I D E time, it was also published in Grinch’s heart grows three sizes, THIS ISSUE: Redbook magazine. It proved so Each shoe weighed 11 pounds we cheer in our own hearts and popular that a famous producer, and the make up took hours to sing right along with the Whos Sports 2 Chuck Jones, decided to make get just right. -

The Horror Film Series

Ihe Museum of Modern Art No. 11 jest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Saturday, February 6, I965 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art Film Library will present THE HORROR FILM, a series of 20 films, from February 7 through April, 18. Selected by Arthur L. Mayer, the series is planned as a representative sampling, not a comprehensive survey, of the horror genre. The pictures range from the early German fantasies and legends, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (I9I9), NOSFERATU (1922), to the recent Roger Corman-Vincent Price British series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe, represented here by THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (I96IO. Milestones of American horror films, the Universal series in the 1950s, include THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), FRANKENSTEIN (1951), his BRIDE (l$55), his SON (1929), and THE MUMMY (1953). The resurgence of the horror film in the 1940s, as seen in a series produced by Val Lewton at RR0, is represented by THE CAT PEOPLE (19^), THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (19^4), I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (19*£), and THE BODY SNAT0HER (19^5). Richard Griffith, Director of the Film Library, and Mr. Mayer, in their book, The Movies, state that "In true horror films, the archcriminal becomes the archfiend the first and greatest of whom was undoubtedly Lon Chaney. ...The year Lon Chaney died [1951], his director, Tod Browning,filmed DRACULA and therewith launched the full vogue of horror films. What made DRACULA a turning-point was that it did not attempt to explain away its tale of vampirism and supernatural horrors. -

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare. Julius Caesar The Shakespeare Ralph Richardson, Anthony SRS Caedmon 3 VG/ Text Recording Society; Quayle, John Mills, Alan Bates, 230 Discs VG+ Howard Sackler, dir. Michael Gwynn Anthony And The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cleopatra Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 235 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Great Scenes The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, TC- Caedmon 1 VG/ Text from Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 1183 Disc VG+ Anthony And Howard Sackler, dir. Cleopatra Titus The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Maxine SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Andronicus Recording Society; Audley, Michael Horden, Colin 227 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Blakely, Charles Gray Pericles The Shakespeare Paul Scofield, Felix Aylmer, Judi SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Dench, Miriam Karlin, Charles 237 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Gray Cymbeline The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Boris Karloff, SRS- Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Pamela Brown, John Fraser, M- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Alan Dobie 236 The Comedy The Shakespeare Alec McCowen, Anna Massey, SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Of Errors Recording Society; Harry H. Corbett, Finlay Currie 205- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. S Venus And The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Max Adrian SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Adonis and A Recording Society; 240 Discs Lover's Howard Sackler, dir. Complaint Troylus And The Shakespeare Diane Cilento, Jeremy Brett, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cressida Recording Society; Cyril Cusack, Max Adrian 234 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. King Richard The Shakespeare John Gielgud, Keith Michell and SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text II Recording Society; Leo McKern 216 Discs Peter Wood, dir. -

BEYOND the BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100

BEYOND THE BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100 BEYOND THE BASICS – Contents Page 1 of 37 CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................. 4 FOR FULL ORCHESTRA ................................................................. 5 Bernstein on Broadway ........................................................... 5 Bernstein and The Ballet ......................................................... 5 Bernstein and The American Opera ........................................ 5 Bernstein’s Jazz ....................................................................... 6 Borrow or Steal? ...................................................................... 6 Coolness in the Concert Hall ................................................... 7 First Symphonies ..................................................................... 7 Romeos & Juliets ..................................................................... 7 The Bernstein Beat .................................................................. 8 “Young Bernstein” (working title) ........................................... 9 The Choral Bernstein ............................................................... 9 Trouble in Tahiti, Paradise in New York .................................. 9 Young People’s Concerts ....................................................... 10 CABARET.................................................................................... 14 A’s and B’s and Broadway .................................................... -

Conyers Old Time Radio Presents the Scariest Episodes of OTR

Conyers Old Time Radio Presents the Scariest Episodes of OTR Horror! Playlist runs from ~6:15pm EDT October 31st through November 4th (playing twice through) War of the Worlds should play around 8pm on October 31st!! _____________________________________________________________________________ 1. OTR Horror ‐ The Scariest Episodes Of Old Time Radio! Fear You Can Hear!! (1:00) 2. Arch Oboler's Drop Dead LP ‐ 1962 Introduction To Horror (2:01) 3. Arch Oboler's Drop Dead LP ‐ 1962 The Dark (8:33) 4. Arch Oboler's Drop Dead LP ‐ 1962 Chicken Heart (7:47) 5. Quiet Please ‐ 480809 (060) The Thing On The Fourble Board (23:34) 6. Escape ‐ 491115 (085) Three Skeleton Key starring Elliott Reid, William Conrad, and Harry Bartell (28:50) 7. Suspense ‐ 461205 (222) House In Cypress Canyon starring Robert Taylor and Cathy Lewis (30:15) 8. The Mercury Theatre On The Air ‐ 381030 (17) The War Of The Worlds starring Orson Welles (59:19) 9. Fear on Four ‐ 880103 (01) The Snowman Killing (28:41) 10. Macabre ‐ 620108 (008) The Edge of Evil (29:47) 11. Nightfall ‐ 800926 (13) The Repossession (30:49) 12. CBS Radio Mystery Theater ‐ 740502 (0085) Dracula starring Mercedes McCambridge (44:09) 13. Suspense ‐ 550607 (601) Mary Shelley's Frankenstein starring Stacy Harris and Herb Butterfield (24:27) 14. Mystery In The Air ‐ 470814 (03) The Horla starring Peter Lorre (29:49) 15. The Weird Circle ‐ 450429 (74) Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde (27:20) 16. The Shadow ‐ 430926 (277) The Gibbering Things starring Bret Morrison and Marjorie Anderson (28:24) 17. Lights Out ‐ 470716 (002) Death Robbery starring Boris Karloff (29:16) 18. -

A Survey of the Right of Publicity: an Overview

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 1 Number 1 Article 10 1-1-1981 A Survey of the Right of Publicity: An Overview Ronald G. Rosenberg Gregory S. Koffman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ronald G. Rosenberg and Gregory S. Koffman, A Survey of the Right of Publicity: An Overview, 1 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 165 (1981). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol1/iss1/10 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY: AN OVERVIEW I. INTRODUCTION This comment surveys the development of California law concern- ing the right of publicity. Although its roots are found in the right of privacy, the right of publicity has become a distinctly different cause of action which has evolved in a relatively short period of legal history. This phenomenon suggests that the expansion of the right of publicity is a response to the growing needs in this century to protect the public personality. Whether the status was attained voluntarily or by some incident deemed newsworthy, the right of privacy previously had not proven to afford the necessary safeguards nor the appropriate remedies. -

1931 FRANKENSTEIN Film Set for Screening with New Score by UT

⌂ BWW MEET THE TEAM Log In Register Now TV TODAY TV NETWORKS SCOOPS RECAPS INTERVIEWS Enter Search... ! MUSIC FOOD+WINE BOOKS ART COMEDY DANCE CLASSICAL OPERA TRAVEL FITNESS THEATER 1931 FRANKENSTEIN Film Set for Screening TV VIDEOS with New Score by UT Wind Ensemble Tonight 12:30 $ by TV News Desk Print Article October 29 2015 Email Link Like Share 0 Tweet 0 Texas Performing Arts presents a screening of the1931 film VIDEO: Carrie Underwood Talks Music, FRANKENSTEIN, starring Boris Karloff as the Frankenstein Motherhood and Her Idol monster, featuring a new film score by composer Michael Shapiro performed by The University of Texas Wind Ensemble, Jerry F. Junkin, conductor. The first half of the program features the UT Wind Ensemble performing Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor and Dukas' The Sorcerer's Apprentice, with video projections designed by UT graduate Stephanie Busing. Unlike The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) with its lush score by Franz Waxman, the 1931 FRANKENSTEIN was produced without a movie score. Movie critics have remarked that Frankenstein is badly in need of music, and American composer Michael Shapiro was up to the task with a commission for a new film score from the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Mr. Shapiro's 70-minute score is orchestrated for wind ensemble and will be performed by UT's renowned wind ensemble. For modern day moviegoers, Mr. Shapiro's haunting music adds significantly to the emotional impact of the film. Michael Shapiro's works, which in the aggregate address nearly every medium, have been performed widely throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe -- with broadcasts of premieres on National Public Radio, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Israel Broadcasting Authority, Sender Freies Berlin, WQXR, and WCBS-TV. -

Boris Karloff in British Columbia by Greg Nesteroff

British Columbia Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation | Vol.39 No.1 2006 | $5.00 This Issue: Karloff in BC | World War One Mystery | Doctors | Prison Escapes | Books | Tokens | And more... British Columbia History British Columbia Historical Federation Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation A charitable society under the Income Tax Act Organized 31 October 1922 Published four times a year. ISSN: print 1710-7881 !online 1710-792X PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 British Columbia History welcomes stories, studies, and news items dealing with any aspect of the Under the Distinguished Patronage of Her Honour history of British Columbia, and British Columbians. The Honourable Iona Campagnolo. PC, CM, OBC Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia Please submit manuscripts for publication to the Editor, British Columbia History, Honourary President Melva Dwyer John Atkin, 921 Princess Avenue, Vancouver BC V6A 3E8 e-mail: [email protected] Officers Book reviews for British Columbia History,, AnneYandle, President 3450 West 20th Avenue, Jacqueline Gresko Vancouver BC V6S 1E4, 5931 Sandpiper Court, Richmond, BC, V7E 3P8 !!!! 604.733.6484 Phone 604.274.4383 [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] First Vice President Patricia Roy Subscription & subscription information: 602-139 Clarence St., Victoria, B.C., V8V 2J1 Alice Marwood [email protected] #311 - 45520 Knight Road Chilliwack, B. C.!!!V2R 3Z2 Second Vice President phone 604-824-1570 Bob Mukai email: [email protected] 4100 Lancelot Dr., Richmond, BC!! V7C 4S3 Phone! 604-274-6449!!! [email protected]! Subscriptions: $18.00 per year Secretary For addresses outside Canada add $10.00 Ron Hyde #20 12880 Railway Ave., Richmond, BC, V7E 6G2!!!!! Phone: 604.277.2627 Fax 604.277.2657 [email protected] Single copies of recent issues are for sale at: Recording Secretary Gordon Miller - Arrow Lakes Historical Society, Nakusp BC 1126 Morrell Circle, Nanaimo, BC, V9R 6K6 [email protected] - Book Warehouse, Granville St. -

List of Shows Master Collection

Classic TV Shows 1950sTvShowOpenings\ AdventureStory\ AllInTheFamily\ AManCalledShenandoah\ AManCalledSloane\ Andromeda\ ATouchOfFrost\ BenCasey\ BeverlyHillbillies\ Bewitched\ Bickersons\ BigTown\ BigValley\ BingCrosbyShow\ BlackSaddle\ Blade\ Bonanza\ BorisKarloffsThriller\ BostonBlackie\ Branded\ BrideAndGroom\ BritishDetectiveMiniSeries\ BritishShows\ BroadcastHouse\ BroadwayOpenHouse\ BrokenArrow\ BuffaloBillJr\ BulldogDrummond\ BurkesLaw\ BurnsAndAllenShow\ ByPopularDemand\ CamelNewsCaravan\ CanadianTV\ CandidCamera\ Cannonball\ CaptainGallantOfTheForeignLegion\ CaptainMidnight\ captainVideo\ CaptainZ-Ro\ Car54WhereAreYou\ Cartoons\ Casablanca\ CaseyJones\ CavalcadeOfAmerica\ CavalcadeOfStars\ ChanceOfALifetime\ CheckMate\ ChesterfieldSoundOff\ ChesterfieldSupperClub\ Chopsticks\ ChroniclesOfNarnia\ CimmarronStrip\ CircusMixedNuts\ CiscoKid\ CityBeneathTheSea\ Climax\ Code3\ CokeTime\ ColgateSummerComedyHour\ ColonelMarchOfScotlandYard-British\ Combat\ Commercials50sAnd60s\ CoronationStreet\ Counterpoint\ Counterspy\ CourtOfLastResort\ CowboyG-Men\ CowboyInAfrica\ Crossroads\ DaddyO\ DadsArmy\ DangerMan-S1\ DangerManSeason2-3\ DangerousAssignment\ DanielBoone\ DarkShadows\ DateWithTheAngles\ DavyCrockett\ DeathValleyDays\ Decoy\ DemonWithAGlassHand\ DennisOKeefeShow\ DennisTheMenace\ DiagnosisUnknown\ DickTracy\ DickVanDykeShow\ DingDongSchool\ DobieGillis\ DorothyCollins\ DoYouTrustYourWife\ Dragnet\ DrHudsonsSecretJournal\ DrIQ\ DrSyn\ DuffysTavern\ DuPontCavalcadeTheater\ DupontTheater\ DustysTrail\ EdgarWallaceMysteries\ ElfegoBaca\ -

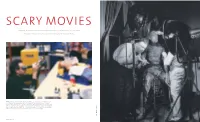

Fright—In All of Its Forms—Has Always Been an Essential Part of the Moviegoing Experience

SCARY MOVIES Fright—in all of its forms—has always been an essential part of the moviegoing experience. No wonder directors have figured out so many ways to horrify an audience. FINAL TOUCHES: (opposite) Director Karl Freund and makeup artist Jack P. Pierce spent eight hours a day applying Boris Karloff’s makeup in The Mummy (1932). This was the first directing job for the noted German cinematographer Freund, who was hired two days before production started. (above) John Lafia scopes out Chucky, a doll possessed by the RES soul of a serial killer, in Child’s Play 2 (1990). Lafia made the 18-inch, half-pound plastic U ICT doll seem menacing rather than silly by the clever use of camera angles. P PHOTOS: UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL PHOTOS: 54 dga quarterly dga quarterly 55 BLOOD BATH: Brian De Palma orchestrates the scene in Carrie (1976) in which UNDEAD: George A. Romero, surrounded by his cast of zombies on Dawn of the Carrie throws knives at her diabolical mother, played by Piper Laurie. De Palma Dead (1978), saved on production costs by having all the 35 mm film cast Laurie because he didn’t want the character to be “the usual dried-up old stock developed in 16 mm. He chose his takes, then had them developed crone at the top of the hill,” but beautiful and sexual. in 35. Romero convinced the distributor to release the film unrated. PHOTOFEST PHOTOFEST ) ) RIGHT BOTTOM VERETT; (boTTOM right) right) (boTTOM VERETT; E RTESY: RTESY: U O RES/DREAMWORKS; ( RES/DREAMWORKS; C U NT/ ICT U P NT NT U ARAMO P ARAMO P ) ) LEFT ; (boTTOM left) © © left) (boTTOM ; BOTTOM ; ( ; MGM EVERETT OLD SCHOOL: The Ring Two (2005), with Naomi Watts, was Hideo Nakata’s first CUt-rATE: Director Tobe Hooper got the idea for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre PIONEER: Mary Lambert, on the set of Pet Sematary (1989) with Stephen GOOD LOOKING: James Whale, directing Bride of Frankenstein (1935), originally American feature after directing the original two acclaimed Ring films in Japan.