Lancaster Gatehouse - the Gatehouse Revealed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Place-Names in and Around the Fleet Valley ==== D ==== Daffin Daffin Is a Farm at the Head of the Cleugh of Doon Above Carsluith

Place-names in and around the Fleet Valley ==== D ==== Daffin Daffin is a farm at the head of the Cleugh of Doon above Carsluith. There is a Daffin Tree marked on the 1st edition OS map at Killochy in Balmaclellan parish, and Daffin Hill in this location on current OS maps, across the Dee from Kenmure Castle; Castle Daffin is a hill in Parton parish and a house by Auchencairn. This is likely to be Gaelic *Dà pheiginn ‘two pennylands’. Peighinn is ‘a penny’, but in place-names it refers to a unit of land, based on yield rather than area. It probably originated in the Gaelic-Norse context of Argyll and the southern Hebrides, and was introduced into the south-west by the Gall- Ghàidheil (see Ardwell above). It occurs in place-names in Galloway and, especially, Carrick as ‘Pin- ‘ as first element, ‘-fin’ with ‘softened ‘ph’ after a numeral or other pre-positioned adjective. Originally a pennyland was a relatively small division of a davoch (dabhach, see Cullendoch above), but in the south-west places whose names contain this element appear in mediaeval records as holdings of relatively substantial landowners, comprising good extents of pasture, meadow and woodland as well as the arable core, and yielding much higher taxes than the pennylands further north. Indeed, peighinn may have come to be used more generally in the region for a fairly substantial estate without implying a specific valuation. *Dà pheiginn ‘two pennylands’ would, then, have been a large and productive landholding. However, a Scots origin is also possible, or if the origin was Gaelic, reinterpretation by Scots speakers is possible: daffin or daffen is a Scots word for ‘daffodil’, but as a verb, daffin(g) is ‘playing daft, larking about’. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area

I Contrebis 2000 The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area. Phil Hudson Introduction This paper hopes to provide a chronological outline of the events which were important in creating the landscape changes in the Quernmore forest area. There was movement into the area by prehistoric man and some further incursions in the Anglo- Saxon and the Norse periods leading to Saxon estates and settled agricultural villages by the time of the Norman Conquest. These villages and estates were taken over by the Normans, and were held of the King, as recorded in Domesday. The Post-Nonnan conquest new lessees made some dramatic changes and later emparked, assarted and enclosed several areas of the forest. This resulted in small estates, farms and vaccaries being founded over the next four hundred years until these enclosed areas were sold off by the Crown putting them into private hands. Finally there was total enclosure of the remaining commons by the 1817 Award. The area around Lancaster and Quernmore appears to have been occupied by man for several thousand years, and there is evidence in the forest landscape of prehistoric and Romano-British occupation sites. These can be seen as relict features and have been mapped as part of my on-going study of the area. (see Maps 1 & 2). Some of this field evidence can be supported by archaeological excavation work, recorded sites and artif.act finds. For prehistoric occupation in the district random finds include: mesolithic flints,l polished stone itxe heads at Heysham;'worked flints at Galgate (SD 4827 5526), Catshaw and Haythomthwaite; stone axe and hammer heads found in Quernmore during the construction of the Thirlmere pipeline c1890;3 a Neolithic bowl, Mortlake type, found in Lancaster,o a Bronze Age boat burial,s at SD 5423 5735: similar date fragments of cinerary urn on Lancaster Moor,6 and several others discovered in Lancaster during building works c1840-1900.7 Several Romano-British sites have been mapped along with finds of rotary quems from the same period and associated artifacts. -

Research Issues1 Wybrane Zespoły Bramne Na Śląsku

TECHNICAL TRANSACTIONS 3/2019 ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING DOI: 10.4467/2353737XCT.19.032.10206 SUBMISSION OF THE FINAL VERSION: 15/02/2019 Andrzej Legendziewicz orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-296X [email protected] Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Technology Selected city gates in Silesia – research issues1 Wybrane zespoły bramne na Śląsku – problematyka badawcza Abstract1 The conservation work performed on the city gates of some Silesian cities in recent years has offered the opportunity to undertake architectural research. The researchers’ interest was particularly aroused by towers which form the framing of entrances to old-town areas and which are also a reflection of the ambitious aspirations and changing tastes of townspeople and a result of the evolution of architectural forms. Some of the gate buildings were demolished in the 19th century as a result of city development. This article presents the results of research into selected city gates: Grobnicka Gate in Głubczyce, Górna Gate in Głuchołazy, Lewińska Gate in Grodków, Krakowska and Wrocławska Gates in Namysłów, and Dolna Gate in Prudnik. The obtained research material supported an attempt to verify the propositions published in literature concerning the evolution of military buildings in Silesia between the 14th century and the beginning of the 17th century. Relicts of objects that have not survived were identified in two cases. Keywords: Silesia, architecture, city walls, Gothic, the Renaissance Streszczenie Prace konserwatorskie prowadzone na bramach w niektórych miastach Śląska w ostatnich latach były okazją do przeprowadzenia badań architektonicznych. Zainteresowanie badaczy budziły zwłaszcza wieże, które tworzyły wejścia na obszary staromiejskie, a także były obrazem ambitnych aspiracji i zmieniających się gustów mieszczan oraz rezultatem ewolucji form architektonicznych. -

September-November—2012 Saturday October 6, 2012 Santanoni Farm Newcomb a Short Walk of Just Over a Mile Will Bring Us to the Farm Complex on the Santanoni Preserve

Northern New York Audubon Serving the Adirondack, Champlain, St.Lawrence Region of New York State Mission: To conserve and restore natural ecosystems in the Adirondacks, focusing on birds, other wildlife, and their habitats for the benefit of humanity and the Earth's biological diversity. Volume 40 Number 3 September-November—2012 Saturday October 6, 2012 Santanoni Farm Newcomb A short walk of just over a mile will bring us to the farm complex on the Santanoni Preserve. The 12,500 acre preserve is home to the Santanoni Lodge, built from 1892-93. While we won't be hiking the 4 miles into the Lodge, there are some old buildings at the farm including a beautiful creamery and some great old fields and orchards that we can explore. After the hike, participants can visit the Gatehouse Moose River Plains building that houses a small museum with photos and information about the history 1 Santanoni Farm—Field Trip and renovation efforts at the Lodge. 1 MassawepieArbutus Lake—Field Mire Trip Time: 9 a.m. Meet: At the Adirondack Interpretive Center, 5922 St Rte 28N Newcomb, NY 2 Westport Boat Launch Leader: Charlotte Demers 2 CoonWestport/Essex—Field Mountain Trip Registration: Email to [email protected] or call the AIC at (518) 582-2000 Azure Mountain—Field Trip Saturday, November 3, 2012 2 Wilson Hill to Robert Moses State Arbutus Lake 3 Park—LouisvilleNABA’s Lake Placid & Massena Butterfly (St.Count Lawrence County) Newcomb Participants will hike a 2 mile loop around the shore of Arbutus Lake in the Hunt- President’s Message ington Wildlife Forest. -

The Story of a Man Called Daltone

- The Story of a Man called Daltone - “A semi-fictional tale about my Dalton family, with history and some true facts told; or what may have been” This story starts out as a fictional piece that tries to tell about the beginnings of my Dalton family. We can never know how far back in time this Dalton line started, but I have started this when the Celtic tribes inhabited Britain many yeas ago. Later on in the narrative, you will read factual information I and other Dalton researchers have found and published with much embellishment. There also is a lot of old English history that I have copied that are in the public domain. From this fictional tale we continue down to a man by the name of le Sieur de Dalton, who is my first documented ancestor, then there is a short history about each successive descendant of my Dalton direct line, with others, down to myself, Garth Rodney Dalton; (my birth name) Most of this later material was copied from my research of my Dalton roots. If you like to read about early British history; Celtic, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Knight's, Kings, English, American and family history, then this is the book for you! Some of you will say i am full of it but remember this, “What may have been!” Give it up you knaves! Researched, complied, formated, indexed, wrote, edited, copied, copy-written, misspelled and filed by Rodney G. Dalton in the comfort of his easy chair at 1111 N – 2000 W Farr West, Utah in the United States of America in the Twenty First-Century A.D. -

Naval Dockyards Society

20TH CENTURY NAVAL DOCKYARDS: DEVONPORT AND PORTSMOUTH CHARACTERISATION REPORT Naval Dockyards Society Devonport Dockyard Portsmouth Dockyard Title page picture acknowledgements Top left: Devonport HM Dockyard 1951 (TNA, WORK 69/19), courtesy The National Archives. Top right: J270/09/64. Photograph of Outmuster at Portsmouth Unicorn Gate (23 Oct 1964). Reproduced by permission of Historic England. Bottom left: Devonport NAAFI (TNA, CM 20/80 September 1979), courtesy The National Archives. Bottom right: Portsmouth Round Tower (1843–48, 1868, 3/262) from the north, with the adjoining rich red brick Offices (1979, 3/261). A. Coats 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the MoD. Commissioned by The Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England of 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, EC1N 2ST, ‘English Heritage’, known after 1 April 2015 as Historic England. Part of the NATIONAL HERITAGE PROTECTION COMMISSIONS PROGRAMME PROJECT NAME: 20th Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth (4A3.203) Project Number 6265 dated 7 December 2012 Fund Name: ARCH Contractor: 9865 Naval Dockyards Society, 44 Lindley Avenue, Southsea, PO4 9NU Jonathan Coad Project adviser Dr Ann Coats Editor, project manager and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Davies Editor and reviewer, project executive and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Evans Devonport researcher David Jenkins Project finance officer Professor Ray Riley Portsmouth researcher Sponsored by the National Museum of the Royal Navy Published by The Naval Dockyards Society 44 Lindley Avenue, Portsmouth, Hampshire, PO4 9NU, England navaldockyards.org First published 2015 Copyright © The Naval Dockyards Society 2015 The Contractor grants to English Heritage a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, perpetual, irrevocable and royalty-free licence to use, copy, reproduce, adapt, modify, enhance, create derivative works and/or commercially exploit the Materials for any purpose required by Historic England. -

Signal Hill National Historic Park

Newfoundland Signal Hill National Historic Park o o o o S2 o r m D Brief History Signal Hill, a natural lookout commanding theapproachesto St. John's harbour played a significant role in the history of Newfound land. Although the island became a military stronghold in the 1790's, Vikings probably landed as early as the 10th century, when they were carried there by wind and current. Later, the island's existence was common knowledge among European fishermen, who called the land on their maps Bacca- laos (cod) in tribute to the silvery fish which drew them across the Atlantic Ocean. Fishing expeditions were greatly encour aged by the voyages of exploration at the end of the 15th century. John Cabot from England in 1497 and 1498, and Jacgues Cartier, from France in 1534, acclaimed the natural wealth of the Grand Banks off New foundland. As the fishing industry grew its methods changed. Fleets had been leaving Europe in the spring and returning in the autumn, but in the 16th century some fishermen began to winter in Newfoundland, building smaii settlements along the coast. The was used as a signalling station. To aiert 1713), France was permitted to continue French settled around Placentia and the the town, cannons were fired at the ap fishing off Newfoundland, but the island English near St. John's. Even without the proach of enemy or friendly ships heading became England's property. support of their governments these first for St. John's or neighbouring Quidi Vidi. During the Seven Years' War between colonists felt the areas they occupied be Unfortunately the warning system and France and England (1756-63), France ex longed to their countries and they under new defences proved ineffective against perienced a number of severe reverses in took to fortify their settlements. -

MA Dissertatio

Durham E-Theses Northumberland at War BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST How to cite: BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST (2016) Northumberland at War, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11494/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT W.E.L. Broad: ‘Northumberland at War’. At the Battle of Towton in 1461 the Lancastrian forces of Henry VI were defeated by the Yorkist forces of Edward IV. However Henry VI, with his wife, son and a few knights, fled north and found sanctuary in Scotland, where, in exchange for the town of Berwick, the Scots granted them finance, housing and troops. Henry was therefore able to maintain a presence in Northumberland and his supporters were able to claim that he was in fact as well as in theory sovereign resident in Northumberland. -

Lochranza Castle Statement of Significance

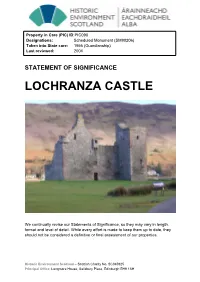

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC090 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90206) Taken into State care: 1956 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE LOCHRANZA CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH LOCHRANZA CASTLE BRIEF DESCRIPTION Lochranza Castle occupies a low, gravelly peninsula projecting into Loch Ranza on the north coast of Arran and was constructed during the late 13th or early 14th centuries as a two-storey hall house. -

Please Allow 28 Days for the Dispatch of All Goods

Visit our online shop at www.ndfhs.org.uk - Page 1 of 128 - (ALL) UK/EU O/seas type NORTHUMBERLAND AND DURHAM FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY A Charity Registered in England: Registered Number 510538 May 2019 - ALL PUBLICATIONS (OTHER THAN CENSUS) IN BOOK, CD-ROM AND MICROFICHE FORM - NEW PRICE LIST & ORDER FORM (Incorporates postal increases effective from 29th March 2016) Please send your order to: Catalogue Sales, NDFHS, Percy House (7th Floor), Percy Street, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 4PW All other correspondence should be directed to the Secretary (see inside the front cover of the Journal for contact details). Please make cheques payable to ‘NDFHS’ and not to an individual. Overseas purchasers may pay by sterling cheque, sterling money order, or US dollar bills. Because of the high transaction charges, we are no longer able to offer credit card facilities at our research centre. Credit Card Purchases (and Paypal) may be made by using our online shops at www.ndfhs.org.uk THIS LIST REPLACES ALL EARLIER LISTS Recent new publications are shown in bold in the list. Please allow 28 days for the dispatch of all goods. CUMBERLAND - PARISH TRANSCRIPTS (BOOKS, FICHE, CDS) Price O/seas Type Postage charges are included in the quoted prices - please allow 28 days for delivery What you see and what you get is what we have at Percy House, our Research Centre - Typed - Handwritten etc. just as it comes. Books are printed on demand. We do not hold stocks. For Monumental Inscriptions the date shows the year to which they are recorded AI_CUL_028 Addingham & Melmerby Baptisms, Marriages & Burials 1813-1839 in datal order £2.25 £2.25 fiche AI_CDCW_001 Addingham Baptisms 1813-1839 - in datal order, searchable £7.25 £7.25 cd AI_CDCW_002 Addingham Burials 1813-1839 - in datal order, searchable £7.25 £7.25 cd AI_CDCW_003 Addingham Marriages 1813-1839 - in datal order, searchable £7.25 £7.25 cd AI_CUL_026_CD Alston & Garrigill Baptisms, Marriages & Burials 1813-1839 - in datal order, £20.25 £20.25 cd searchable transcribed by C.