The Discovery of America, the Several Lectures Being As Follows : the Results of the Crusades," by F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Fisherrow Yacht Club R$Mrnow 0131665 5900 HA.RBOI]RM Sitf,R 3 Stoneyhillgrove Musselburgh EH216SE L..--- IIANDEOOK 2OOE 0Ryc-> L ;;1* 0Fyc>' EANDBOOK 2OO8](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7088/fisherrow-yacht-club-r-mrnow-0131665-5900-ha-rboi-rm-sitf-r-3-stoneyhillgrove-musselburgh-eh216se-l-iiandeook-2ooe-0ryc-l-1-0fyc-eandbook-2oo8-327088.webp)

Fisherrow Yacht Club R$Mrnow 0131665 5900 HA.RBOI]RM Sitf,R 3 Stoneyhillgrove Musselburgh EH216SE L..--- IIANDEOOK 2OOE 0Ryc-> L ;;1* 0Fyc>' EANDBOOK 2OO8

Fisherrow YachtClub MembersHandbook 2008 EANDBOOK2NS [ii"->v'.-'* CONTENIS COMMODORES MESSAGE FLAGOFFICTRS AND COMMITTEE"''"...''"....".' CLUBWEB SIT8....... 6 MEMBERSHlP TIDE TABLES CLUB COURSES CONDMONSOF ENTRY usEoF CLUBDINCHIES. .... ...... .... .. " 31 usE oF cLuB SAFETY8OATS... ..... ........ ". 32 CRUSIERAND DINGIIY RACING ''''- -- - -- YACI{T SAFETYEQUIPMENT DINGIIY SAFETYEQT'IPMENT SAILINGCALENDAR 2008 .... .. ... .... " 44 FORTHYACI{I CLIJBASSOCIATION EVENTS 2008 """"" SOCLA.LCALENDAR -;Y-c"' llANlrD0or 200r IlTb--, EANDAOOK2,UE COMMODORI,ISMESSAGE TI"AG OXIICERS AND COMMITTDE f,ONORARY COMMODORE Alex Stewart,Harbourmaster Wdcona to thc 20{8 |rltltrg rc$otr. COMMODORE .la'rc Tierney 01316641863 184 Giln€rton Dyk€slhiv€ I lopofully lhis ycar the weatherwill give us a moro co[sistelt seasotrthatr we sufforedlast Fdinburgh EHIT 8LW flc0ron. 'l'he sailing calcndar is looking promising, the midweek raceshave beetrdropped but tho sohcdulethis year is prominendy geared to weekendracitrg and cruisiag, with a couple of VICE OOMMODORE Chris Tierney 0l3l 5619441 picnios thrown in for good measure. Hop€fitlly this wil briry as many ofyou and yourtrotr SAILING Sf,CRf,TARY 58 Sixth SEeet sliling prrtners out otrto lhe wate! or beachto join in with the aotivities plannedfor the year. Newtongmnge (rcmcmber the sailing cale4daris not set itr sto&, and caa be ohangedas aod when required). EH22 4LA D€mis waltotr 0r3r 66s8227 In Junc, REAN,COMMODONT the Routrd Britain Powcr Boat Rac€ arrives in the Fortt- firrther details ofour HOUSE CONVENER 16 Carb€rryRoad pdioipation \ r'ith the organisersoflhis eveN will be givetr in the newsletter latei. Inveresk EHzI 7TN FYC Regartaweekend is followhg a similar format to last year, so pencil ia the vr€ekeDdof Carol Jone3 0r3r 66r t679 thc 160-I70 Augusl to your diaries. -

Jeanneau Eolia 25 Price

Jeanneau Eolia 25 Network ID 171152 Power/Sail Sailboat Year 1984 Engines 1 Fuel Diesel Construction GRP Location Dartmouth, Devon LOA 24' 0" (7.32m) Keel Lifting ... Max Draft 4' 11" (1.5m) Displacement 8,245 lbs Beam 9' 2" (2.79m) Berths 4 LWL 21' 8" (6.60m) Heads 1 Showers 1 Watertank Size 20 Litres Horsepower 9 Drive Type Shaft drive Fueltank Size 25 Litres Cruise Speed 5 Top Speed 6 knots Rig Type Sloop Price: £11,950 Accommodation Detail Mechanical and Rigging Built by Jeanneau in 1984 to a design by Philippe Briand GRP hull, deck and superstructure Lifting Keel Tiller Steering Hull re-lined and reupholstered (2011) Windows replaced (2011) Mechanical: Yanmar 1GM10 9hp diesel engine (2013) Fuel consumption 1.0 litre / hour at cruising speed Raw water cooled Shaft Drive 3-blade propeller Electrics: 12v system supplied by 2-batteries Charged by engine alternator Electrics including custom made switch and fuse board (2011) Tankage: Fuel capacity 25 litres in 1x tank Fresh water capacity 20 litres in 1 x tank Rigging: Bermudan masthead sloop Alloy spars Stainless steel standing rigging (2011) Furlex headsail reefing (2011) Sails: Fully battened main in stack pack (2011) Genoa (2012) Winches: 1 x Halyard winch 2 x Sheet winches Inventory Navigation Equipment: Compass Speed Log Wind VHF GPS Chart plotter (2011) Ground Tackle: Anchor with warp and chain General Equipment: Mainsail cover Sprayhood All over winter cover (2013) Warps Fenders Boathook Cabin lights Dodgers (2011)_ Safety Equipment: Navigation lights Manual bilge pump Electric bilge pump Accommodation Sleeps 4 in 2 double berths in two cabins including saloon The saloon area has a lovely open feel to it, with two settee berths either side of the dining table. -

Page 1 of 3 VELUM Ng

VELUM ng - Wettfahrt Page 1 of 3 Yachtclub Rheindelta Blue Planet - Flug-Trophy Rohrspitz-Regatta 22. - 23. September 2007 L20705001 Yachtclub Rheindelta Gesamtergebnis Wettfahrten: 1,2 Low-Point (Kat. C) Wettfahrtleitung: Markus Düringer Schiedsgericht: Dieter Härtl Auswertung: Edith Müller/ Ivo Gonzenbach Organisation: Yachtclub Rheindelta 24.09.2007 - 19:33:37 Wettfahrten: 1.Wf, 2.Wf G- NAT SEGELNR BOOTSNAME STEUERMANN/- BOOTSTYP CLUB YST GES.ZEIT BER.ZEIT PL. PKT GES.ZEIT BER.ZEIT PL. PKT G- G- PL FRAU (1.WF) (1.WF) (1.Wf) (1.Wf) (2.WF) (2.WF) (2.Wf) (2.Wf) PKTE PL CREW Robert 1 C 25 Coronado Coronado 25 YCRhd 113 03:27:37 03:03:44 3 3,00 01:57:35 01:44:03 12 12,00 15,00 1 Schönbeck Claudine 2 SUI 2034 Schweizeins Koellmann H-Jolle SVK 92 02:58:14 03:13:44 16 16,00 01:24:57 01:32:20 2 2,00 18,00 2 Ralf Luckas Dietmar 3 AUT 179 GO ON Nissen 424 YCRhd 81 02:34:11 03:10:21 8 8,00 01:23:10 01:42:40 11 11,00 19,00 3 Salzmann 4 SUI 37 G-Force Sven Niklaus G-Force 37 BSC 86 02:46:26 03:13:32 15 15,00 01:26:28 01:40:33 8 8,00 23,00 4 Gerhard 5 AUT Santé Dehler 28 YCWW 104 03:19:01 03:11:22 10 10,00 01:54:29 01:50:05 27 27,00 37,00 5 Hannesschläger Ivo Gonzenbach YCRhd 6 AUT 4 dicka Frosch Int 14 88 02:55:16 03:19:10 33 33,00 01:26:06 01:37:50 5 5,00 38,00 6 Martina Müller YCRhd Dehler 33 7 AUT 122 Boreas Helmut Lenz YCRhd 91 02:58:51 03:16:32 24 24,00 01:35:32 01:44:59 15 15,00 39,00 7 COMP 8 AUT 938 Fabienne Albert Lässer Eolia 25 YCRhd 111 03:25:40 03:05:17 5 5,00 02:04:38 01:52:17 37 37,00 42,00 8 Roelof 9 GER 3662 Windliese Tabasko-s YCL -

SLVYRA List of Rated Yachts As of August 15Th 2019 Liste ARVSL Des Voiliers Mesurés En Date Du 15 Aout 2019

SLVYRA list of rated yachts as of August 15th 2019 Liste ARVSL des voiliers mesurés en date du 15 Aout 2019 NO. NOM/NAME TYPE CLUB LAC CODE SPI T/T T/D CODE VB T/T T/D CLAS. HDCP 0 SOLACE ALBERG 22-1 RO O 555K 0.891 282 5B5K 0.874 300 VB(3) base 0 DIANA ALBERG 29-1 ZZ S553 0.929 243 SC53 0.908 264 VB(2) base 0 TRAIL WIND ALBERG 29-1 ZZ 5555 0.945 228 5B55 0.926 246 VB(2) base 0 L'ADDITION ALBIN VEGA 27-1 PC StL(1) 5555 0.926 246 5B55 0.908 264 VB(2) base 0 REAL ESCAPE ALBIN VEGA 27-1 B StL(1) 5555 0.926 246 5B55 0.908 264 VB(2) base 0 COOL SEAS (226) ALBIN VEGA 27-1 ZZ 5555 0.926 246 5B55 0.908 264 VB(2) base 0 REYKJAVIK 2 ALOHA 8.2/27-1 L D-M 5555 0.962 213 5B55 0.942 231 VB(2) base 0 THALASSA (073) ALOHA 8.2/27-1 B StL(1) 5555 0.962 213 5B55 0.942 231 VB(2) base 0 WANDERLUST ALOHA 8.5/28-1 B StL(1) 5555 0.982 195 5B55 0.962 213 VB(2) base 0 SHE CAT ALOHA 8.5/28-1 RO O 3555 0.975 201 3B55 0.955 219 VB(2) mes. 0 CIAO ALOHA 8.5/28-1 SF StF 5555 0.982 195 5B55 0.962 213 2 base 0 SHANGRILA ALOHA 8.5/28-1 SF StF 5555 0.982 195 5B55 0.962 213 VB(2) base 0 LA PIAULE 2 ANNAPOLIS 26-1 S D-M 457M 0.955 219 4B7M 0.936 237 VB(3) base 0 ZEN BAYFIELD 25-1 S D-M 2543 0.885 288 2C43 0.865 309 VB(3) mes. -

YARDSTICKZAHLEN 2021 Inklusive Einführung in Das System Und Regeln

Aktualisierung: Januar 2021 YARDSTICKZAHLEN 2021 Inklusive Einführung in das System und Regeln 4531279 Informationen für Mitglieder des Deutschen Segler-Verbands Aktualisierung: Januar 2021 YARDSTICKZAHLEN 2021 Inklusive Einführung in das System und Regeln HIGH GLOSS — DURABLE & REPAIRABLE — TRUE COLOR NEXT GENERATION TOPCOAT 45 1279 awlgrip.com 3 facebook.com/awlgripfinishes twitter.com/awlgrip instagram.com/awlgripfinishes All trademarks mentioned are owned by, or licensed to, the AkzoNobel group of companies. Informationen für Mitglieder des Deutschen Segler-Verbands © AkzoNobel 2021. 9861/0121 IPL0121879480-001_Awlgrip_HDT_IT_105x148.indd 1 22/01/2021 10:46 Yardstick Deutschland Yachten desselben Serientyps, für die eine YS-Zahl gilt, müssen Von Dietrich Kralemann also dieselben Konstruktionsmerkmale des Rumpfes (Tiefgang, Motorausrüstung, Verdrängung, Kielgewicht, Kielform und -mate- Motto: Fair segeln, mit fairen Mitteln gewinnen! rial u. ä.) und denselben Ausrüstungsstandard von Rigg und Segeln aufweisen. 1. Allgemeine Zielsetzungen Bei den vom DSV anerkannten Klassen und Werftklassen gibt es in Der DSV beabsichtigt mit dem von ihm propagierten und jährlich dieser Hinsicht keine Probleme. aktualisierten Yardsticksystem, das Regattasegeln mit baugleichen Aber auch für die übrigen Serienyachten ist der Standard durch De- Serienyachten und Jollentypen zu fördern. finition und Beschreibung im YS-Grundstandard verbindlich festge- Dabei sollen zeitlicher und finanzieller Vermessungsaufwand für legt. Für den Rumpf sind Kielform, ggf. -

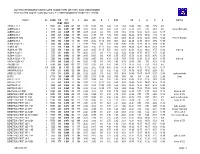

Yardstick Bodensee Februar 2018 Klasse Oder Namen Des

Yardstick Bodensee Februar 2018 Klasse oder Namen des Einzelbootes Eib TR Hk Segelmasse Typ YSZ Datum 1 Tonner Brava x 49/44/103 Kb 8621.09.2011 1 Tonner Bremen Eib x 44/42/93 Kb 9207.01.2015 1 Tonner High Noon x 36/49/115 Kb 9219.01.2012 1/2 Tonner Brigantia Eib x 26/25/61 Kb 97 07.01.2015 1/2 Tonner Gilardoni 915 15/31/65 Kb 107 28.04.2014 1/2 Tonner Ringelnatz Eib x 30/43/120 Kb 86 07.01.2015 1/4 Tonner Caipirina x 15/30/95 Kb 96 26.06.2011 1/4 Tonner Quadriga x 23/19/48 Kb 9612.08.2010 1/4 Tonner Saftiger Apfel 20 Eib x 22/16/37 Kb 101 07.01.2015 1/4-Tonner Tequilla x 11/20/45 Kb 110 11m OD 28/13/84 Kb 91 11m OD Top 28/41/86 Kb 86 11m Yacht Margaritta 7/8 x 33/34/90 Kb 91 11.04.2011 12 Fuss Dinghy 9,5/-/- Jol 12702.06.2015 12m OD 51/31/110 Kb 8128.06.2009 14 Footer 13/ 6/27 Jol 88 14 Fuss Dinghy 12/6/-- Jol 13403.01.2016 15 m2 SNS Classic 11/14/50 Kb 108 15 m2 SNS Modern 11/14/50 Kb 10414.01.2013 15er Jollenkreuzer Jkr 10019.01.2009 15er Jollenkreuzer Gaffel Tümmler x 11/09/28 Jkr 108 24.04.2012 15er Jollenkreuzer Judith Eib x 12/12/26 Jkr 105 10.01.2014 15er Jollenkreuzer Kniickspant Jkr 110 15er Jollenkreuzer Meteor x Jkr 10319.01.2009 15er Jollenkreuzer Zalou x 10/12/50 Jkr 109 19.01.2012 15er R Schärenkreuzer 11/13/32 Kb 101 09.01.2006 16er Jollenkreuzer Carpe Diem 09/08/32 Jol 112 27.11.2015 16er Jollenkreuzer Kneissel Jkr 10819.01.2012 18 Footer 24/-9/74 Jol 7611.01.2011 2 Tonner Carina x 35/75/160 Kb 93 2 Tonner Raring II x 26/53/120 Kb 98 2 Tonner Shamrock x 36/72/172 Kb 94 2.4m R 5/2,5/-- Kb 13029.04.2016 20 er Jollenkreuzer -

Liste Der Archivierten Bootstypen (Bootstyp Alphabetisch Sortiert)

Liste der archivierten Bootstypen (Bootstyp alphabetisch sortiert) Quelle Nr. Jahr Bootstyp Länge [m] Breite [m] Tiefgang [m] Neupreis Yacht 10 72 808 8,08 2,08 1,60 17.760,00 DM Yacht 16 81 12m R Yacht Westwind 21,45 3,60 2,85 Prosp. S 1989 15er Jollenkreuzer 6,50 2,50 0,20 44.440,00 DM Yacht 12 89 15er Jollenkreuzer 6,50 2,44 0,16 26.000,00 DM Prosp. S 1989 16er Jollenkreuzer 7,00 2,40 0,20 39.250,00 DM Prosp. S 1989 20er Jollenkreuzer 7,75 2,50 0,20 50.500,00 DM Prosp. S 1980 39 feet Koster 12,00 4,00 2,10 90.000,00 DM BP 37 80 420er 4,20 1,63 0,17 5.000,00 DM Skipp. 5 90 Abbate Elite 25 7,55 2,38 0,80 Prosp. S 1978 Accent 26 8,05 2,77 1,54 Yacht 21 76 Achilles 24 7,24 2,16 1,14 24.398,00 DM BP 130 80 Acrobat V 430 4,34 1,72 8.500,00 DM Yacht 4 75 Adler 34 10,35 3,20 0,95 153.922,00 DM BP 122 80 Admiral 4,10 1,68 3.995,00 DM Yacht 20 73 Adventurer 24 7,32 2,95 0,80 39.000,00 DM Yacht 12 81 Aegean Mini Ton 234 6,60 2,50 1,37 22.500,00 DM BP 178 80 Akis 22 6,47 2,46 0,65 23.700,00 DM Prosp. -

Veneilyohjelma 2019

2019 Veneilyohjelma LAHDEN PURJEHDUSSEURAN VENEILYOHJELMA 2019 TÄYDEN PALVELUN PALVELUTUKKU KOLMIO OY VENE- JA KONELIIKE PAIKALLINEN, VARMA VALINTA • Myynti • Huolto • Varaosat • Talvisäilytys • Laituripaikat Niemessä V E N E K A U P P A . C O M / V E N E I L I J Ä N P A R A S K A V E R I Palvelutukku Kolmion kalusto valmiina reitille Vääksy: Lahdentie 5 Lahti: Kipparinkuja 2 p. 010 271 7410 p. 010 271 7411 [email protected] [email protected] Hankkimalla ammattikeittiösi tarpeet meiltä: • saat korkean toimitusvarmuuden • saat kokonaisedulliset hinnat ja laadukkaat tuotteet • Venealan monipuolista osaamista • voit tilata oikeasti paikallisia tuotteita • Pitkällä kokemuksella sekä edullisesti • voit tilata yksilöllisiä tuotteita ketjutuotteiden asemasta • Volvo Penta ja Yanmar -huoltotarvikkeet • saat henkilökohtaisen palvelun ja oman myyjän, joka on tavoitettavissa Palvelutukku on juuri sopivan kokoinen kumppani horeca-yrittäjälle. Pieni on pienen puolella. Palvelutukussa keskitymme palvelemaan asiakkaitamme ja auttamaan heitä menestymään. Maanlaajuinen Palvelutukkurit -ketju ei itse operoi ravintolakentällä omien tukkuasiakkaidensa kilpailijana. Myynti, Huolto, Varaosat Yhteydenotot Myyntipäällikkö Erkki Leppänen 040 960 0728 – [email protected] Jalkarannantie 23, 15900 LAHTI Puh. 03-7512 000 [email protected] Gsm 0400-494 540 PALVELUTUKKU KOLMIO Britannic Bold, C=0 M=75 Y=100 K=0 Koko Palvelutukku 100% Kolmio 75% TOIMIHENKILÖT Kommodorin sana Postiluukusta tupsahtanut Lahden Purjehdus- laituri antavat mahdollisuuden vierailla vesi- VENETEKNIIKKA LARES OY seuran vuosikirja on merkki siitä, että uusi teitse saaressa, jossa ravintola palvelee asiak- veneilykausi 2019 on alkanut. Toivottavasti kaita koko kesäkauden. kesän kelit suosivat ja hellivät meitä veneili- Myllysaaren PTS-korjaussuunnitelmaa tullaan jöitä ja muita lomanviettäjiä viimekesäiseen • kuntokartoitukset päivittämään syyskokouksessa. tapaan. -

An Illustrated History of Waterford Connecticut

s V, IN- .Definitive, nv U Haying in Waterford began in 1645 when settlers harvested their first West Farms crop. Farming was the town's chief source of livelihood for its first three centuries. Here haying is being done at Lakes Pond (Lake Konomoc) before the reservoir dam changed the lay of the land in 1872. MILESTONES on the Road to the Portal of Waterford's Third Century of Independence . Waterford's town hall opened in 1984 in the former 1918 Jordan School. Youthful scholars had wended their way to three previous schoolhouses at the Rope Ferry Road address. An ornamental balustrade originally graced the roof of the present structure. I 1~-I II An Illustrated History of the Town of NVA T E: R::F. O.-:R, xD By Robert L. Bachman * With William Breadheft, Photographer of the Contem- porary Scenes * Bicentennial Committee, Town of Waterford, Connecticut, 2000. From the First Selectman A complete and accurate history of our past serves as a guiding light to our future. We are fortunate to have had the collective wisdom of the Bicentennial Committee 1995-99 mem- bers and the fine intellect and experience of author Robert L. Bachman to chronicle the essence of our community's past. The citizens of Waterford are indebted to them for their fine work. Thomas A. Sheridan Bicentennial Committee 1995-99 Ferdinando Brucoli Paul B. Eccard, secretary Arthur Hadfield Francis C. Mullins Ann R. Nye Robert M. Nye, chainnan June W. Prentice and Robert L Bachman Adjunct Afem bers Dorothy B. Care Teresa D. Oscarson Acknowledgments -. -

Katsastetut Veneet 2020.Xlsx

Katsastustoiminnan terveiset 2.12.2020 Kuluvana vuonna korona on vaikeuttanut sekä sekoittanut myös katsastustoimintaa. Kiitämme kaikkia veneen omistajia ymmärryksestä ja yhteistyöstä katsastusasioissa. Kuluneena vuonna korotettuja katsastusmaksuja ei ole veloitettu. Osa peruskatsastuksista kokonaan tai osittain on koronan vuoksi siirretty vuodelle 2021. Siirretyiltä veneiltä ei veloiteta uudestaan maksua peruskatsastuksesta ensi vuonna, vain vuosikatsastusmaksu. Mikäli veneesi on katsastettu vuonna 2020 ja sitä ei löydy listasta, otathan yhteyttä katsastajaasi tiedon oikaisemiseksi. Yhteystiedot LPS nettisivuilla ja veneilyohjelmassa. Tällä tietoa katsastustoiminta palaa normaaliin ensi vuonna ja ensi vuoden lopussa seuran venerekisteristä poistetaan toistuvasti katsastamattomat veneet. Huolehdithan erityisellä tarkkuudella katsastuksesi ensi vuonna, jotta vene voidaan säilyttää LPS venerekisterissä. Erityistilanteista ilmoitathan toimistolle (esim, vene ei vesillä, vene myyty, uusi vene yms.) Kiitos kaudesta ja yhteistyöstä sekä hyvää vuodenvaihteen aikaa! -Katsastustoiminta- Vuonna 2020 katsastettuja veneitä 143, joista peruskatsastuksia 37. Sukunimi Etunimi Muut haltija Veneen nimi Rek.nro Purjenro P/M Tyyppi PK Aarrevaara Timo A19268 M Scand 3000H1 2020 Anttila Juha Sea Cloud L9947 2585 P Finn Express 83 2020 Arjala-Salo Anu Hejssan Saa A54411 3843 P Artina 33 2017 Bengts Carl-Erik Samantta U38486 M Huvivene 2019 Blåfield Tapio Anli H71405 M Retkivene 2018 Blåfield Laura Vaahtonen 09980 M Yamarin 2018 Boman Juhani A26248 M Yamarin -

Comparativa 16-17

Sail Number Yacht Name Class GPH 2017GPH 2016 Delta Delta% ESP-8682 ARNOIA RO 340 664,5 664,4 0,1 0,01504891 ESP-8736 S’AVENC SALONA 37 LK 619,5 621,1 -1,6 -0,2582728 ESP-25308_C SAIL AND SEE BARCELONA FARR PLATU 25 664,2 661,3 2,9 0,43661548 ESP-9518 2 MUCH X-65 487,3 487,4 -0,1 -0,02052124 ESP-10303_C 5 MARES BAVARIA 50 602,8 603,8 -1 -0,1658925 ESP-8045 78 DE MAYO IMX 45 554,2 554,8 -0,6 -0,10826416 ESP-7557 ABELARDO UNO DUFOUR 34 653,6 655,6 -2 -0,30599755 ESP-4130_C ABONICO PUMA 32 744 747,3 -3,3 -0,44354839 ESP-8630_C ABORDAXE ELAN 340 655,3 654,9 0,4 0,06104074 ESP-10299_C ACALA DAIMIO 28 803,7 807,1 -3,4 -0,42304342 ESP-9211_C AD LIBITUM SUN BEAM 39 638,2 638,9 -0,7 -0,10968348 ESP-3108_C ADAGI 3108 OPTIMA 101 690,6 691,4 -0,8 -0,1158413 GBR-3757 ADMIRABLE RED ADMIRAL 668,4 670,8 -2,4 -0,35906643 ESP-9754 ADRIAN HOTELES FIRST 45DK 556,6 557 -0,4 -0,07186489 ESP-3551 AERIS FIRST CLASS 8 687,9 686,8 1,1 0,15990696 ESP-2969_C AGUAMARINA PROTO IOR 1/4 TON 698,4 699,8 -1,4 -0,20045819 ESP-4310_C AGUAZUL BAVARIA 46 CR 611,5 612,3 -0,8 -0,13082584 ESP-10040_C AGUICA 2.0 FURIA 1000 775,1 778,9 -3,8 -0,49025932 ESP-9623_C AGUIEIRA I SUN ODYSSEY 40 664,4 666,5 -2,1 -0,31607465 ESP-9238 AGUILUCHO YATLANT 24 756,9 761,4 -4,5 -0,59453032 ESP-6783_C AGUITA SALA J.O.D. -

And Dimensions Handicaps (Code 555M Ou 5555) Et Dimensions De Base De L'arvsl

SLVYRA STANDARD HANDICAPS (CODE 555M OR 5555) AND DIMENSIONS HANDICAPS (CODE 555M OU 5555) ET DIMENSIONS DE BASE DE L'ARVSL YACHT CL. CODE T/D T/T M R LOA LWL B D DISP I ISP J JC P E NOTES [S/M] [TCF] ABBOTT 22-1 3 555M 237 0.936 OB MH 22.00 18.70 7.50 3.80 3.10 29.00 29.00 9.87 9.87 23.50 8.00 ALBERG 22-1 3 555K 282 0.891 OB MH 22.00 16.00 7.00 3.08 3.20 27.75 27.75 8.75 8.75 24.00 9.50 moteur dans puit ALBERG 29-1 2 5555 228 0.945 IB MH 29.25 22.25 9.08 4.50 9.10 37.00 37.00 12.00 12.00 32.00 12.17 ALBERG 30-1 2 5555 225 0.949 IB MH 30.30 21.70 8.75 4.25 9.00 36.00 36.00 10.50 10.50 31.00 14.25 ALBERG 37 YWL 2 5555 171 1.011 IB YWL 37.17 26.50 10.16 5.50 19.00 44.25 44.25 14.00 14.00 38.50 16.00 Pm=18, Em=6,5 ALBERG 37-1 2 5555 168 1.015 IB MH 37.16 26.43 10.16 5.50 16.80 44.25 44.25 14.00 14.00 38.50 17.50 ALBIN VEGA 27-1 2 5555 246 0.926 IB FR 27.00 23.00 8.00 3.83 5.07 30.83 30.83 10.17 10.17 25.92 10.83 ALOHA 34-1 2 5555 156 1.030 IB MH 34.00 28.67 11.15 5.50 13.60 38.00 38.00 14.00 14.00 32.00 10.87 ALOHA 34-1 TM 2 5555 150 1.038 IB MH 34.00 28.67 11.15 5.50 13.60 43.50 43.50 14.00 14.00 37.75 12.00 mat long ALOHA 8,2/27-1 2 5555 213 0.962 IB FR 26.50 22.17 9.42 4.33 5.20 30.00 30.00 10.75 10.75 31.75 10.25 ALOHA 8,5/28-1 2 5555 195 0.982 IB MH 28.00 24.50 9.42 4.33 6.75 35.50 35.50 12.00 12.00 30.42 10.50 ALOHA 8,5/28-1 TM 2 5555 192 0.986 IB MH 28.00 24.50 9.42 4.33 6.75 37.00 37.00 12.00 12.00 32.00 10.50 mat long AMPHIBICON 26-1 3 555M 246 0.926 OB MH 26.00 21.67 7.50 2.40 3.90 30.00 30.00 9.50 9.50 26.00 12.00 ANCOM 23-1 3