A Pharmacovigilance Study of Association Between Proton Pump

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benzodiazepine Group ELISA Kit

Benzodiazepine Group ELISA Kit Benzodiazepine Background Since their introduction in the 1960s, benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed for the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, muscle spasms, alcohol withdrawal, and seizure-prevention as they are depressants of the central nervous system. Despite the fact that they are highly effective for their intended use, benzodiazepines are prescribed with caution as they can be highly addictive. In fact, researchers at NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) have shown that addiction for benzodiazepines is similar to that of opioids, cannabinoids, and GHB. Common street names of benzodiazepines include “Benzos” and “Downers”. The five most encountered benzodiazepines on the illicit market are alprazolam (Xanax), lorazepam (Ativan), clonazepam (Klonopin), diazepam (Valium), and temazepam (Restori). The method of abuse is typically oral or snorted in crushed form. The DEA notes a particularly high rate of abuse among heroin and cocaine abusers. Designer benzodiazepines are currently offered in online shops selling “research chemicals”, providing drug abusers an alternative to prescription-only benzodiazepines. Data defining pharmacokinetic parameters, drug metabolisms, and detectability in biological fluids is limited. This lack of information presents a challenge to forensic laboratories. Changes in national narcotics laws in many countries led to the control of (phenazepam and etizolam), which were marketed by pharmaceutical companies in some countries. With the control of phenazepam and etizolam, clandestine laboratories have begun researching and manufacturing alternative benzodiazepines as legal substitutes. Delorazepam, diclazepam, pyrazolam, and flubromazepam have emerged as compounds in this class of drugs. References Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control. “Benzodiazepines.” http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugs_concern/benzo_1. -

Glucuronidase-Mediated Reduction of Oxazepam and Temazepam

1 Reduction of temazepam to diazepam and lorazepam to delorazepam during enzymatic 2 hydrolysis 3 4 Shanlin Fu • Anna Molnar • Peter Bowron • John Lewis • Hongjie Wang 5 6 7 8 9 10 S. Fu () · A. Molnar · J. Lewis 11 Centre for Forensic Science, University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), Broadway, NSW, 12 Australia 2007 13 e-mail: [email protected] 14 15 P. Bowron 16 Toxicology Unit, Pacific Laboratory Medicine Services, Macquarie Hospital, North Ryde, 17 NSW, Australia 2113 18 19 H. Wang 20 National Measurement Institute, 1 Suakin Street, Pymble, NSW, Australia 2073 21 22 Page 1 of 29 1 Abstract 2 3 It has been previously reported that treatment of urinary oxazepam by commercial β- 4 glucuronidase enzyme preparations, from Escherichia coli, Helix pomatia, and Patella 5 vulgata, results in production of nordiazepam (desmethyldiazepam) artefact. In this study, we 6 report that this unusual reductive transformation also occurs in other benzodiazepines with a 7 hydroxyl group at the C3 position such as temazepam and lorazepam. As determined by LC- 8 MS analysis, all three enzyme preparations were found capable of converting urinary 9 temazepam into diazepam following enzymatic incubation and subsequent liquid-liquid 10 extraction procedures. For example, when H. pomatia enzymes were used with incubation 11 conditions of 18 h and 50 °C, the percentage conversion, although small, was significant – 12 approximately 1 % (0.59% - 1.54%) in both patient and spiked blank urines. Similarly, using 13 H. pomatia enzyme under these incubation conditions, a reductive transformation of urinary 14 lorazepam into delorazepam (chlordesmethyldiazepam) occurred. These findings have both 15 clinical and forensic implications. -

Flualprazolam Article Originally Appeared in TOXTALK®, Volume 43, Issue 4

Donna Papsun¹, MS, D-ABFT-FT, Craig Triebold², F-ABC, D-ABFT-FT Emerging Drug: ¹NMS Labs, Horsham, PA; ²Sacramento County District Attorney Laboratory of Forensic Services, Sacramento, CA Flualprazolam Article originally appeared in TOXTALK®, Volume 43, Issue 4 In recent years, there has been an increase of misuse related to designer benzodiazepines (DBZD), a subcategory of novel psychoactive substances (NPS). Benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed for their anxiolytic, muscle relaxant, sedative- hypnotic, and anticonvulsant properties, but due to their widespread availability and relatively low acute toxicity, there is a high potential for misuse and dependence. Therefore, in the era of analogs of commonly used substances emerging on the drug market as suitable alternatives, it is not unexpected that designer variants of benzodiazepines have become available and in demand. Compounds of this class may have either been repurposed from pharmaceutical research, chemically modified from prescribed benzodiazepines, or obtained from diversion of pharmaceuticals available in other countries. Flualprazolam, a fluorinated analog of alprazolam, is an emerging designer benzodiazepine with increasing prevalence, which is an example of a modification to a prescribed benzodiazepine. It was first patented in the 1970s but never marketed, so it has been repurposed for recreational abuse from pharmaceutical research as well (1). Its chemical characteristics and structure are listed in Figure 1. Flualprazolam is a high potency triazolo-benzodiazepine with sedative effects similar to other benzodiazepines (2). It is marketed by internet companies for “research purposes” as an alternative to alprazolam and discussions on online forums suggest that flualprazolam lasts longer and is stronger than alprazolam, its non-fluorinated counterpart (3). -

Summary of Product Characteristics 1

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 DENOMINATION OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT DELORAZEPAM ABC 1 mg/ml Oral drops, solution 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION DELORAZEPAM ABC 1 mg/ml Oral drops, solution 1 ml of solution contains: Active principle: delorazepam 1 mg For the excipients, refer to 6.1. 3. Pharmaceutical form Oral drops, solution. 4. CLINIC INFORMATION 4.1 Therapeutical indications Dysphoria, Insomnia. The benzodiazepines are indicated only when the disorder is serious, disabling or the subject is submitted to serious uneasiness. 4.2 Posology and administration modality Anxiety trouble In general medicine -oral drops, solution: 13-26 drops, for 2-3 times a day. In neuro-psychiatry - oral drops, solution: 26-50 drops, for 2-3 times a day. The anxiety trouble treatment should be in terms of time as short as possible. The patient should be regularly re-valued and the necessity of a continued treatment should be attentively evaluated, particularly when the patient is without symptoms. The total treatment duration should not exceed, generally, 8-12 weeks, including a period of gradual suspension. In specific cases, the extension of treatment beyond the maximum period may be necessary; in such case, this should not occur without the patient condition re-evaluation. Insomnia -oral drops, solution: 13-26-52 drops, in the evening before going to sleep. The insomnia treatment, in terms of time, should be as brief as possible. The treatment duration, generally, varies from a few day to two weeks up to a maximum of four weeks, including a period of gradual suspension. In specific cases it may be necessary the extension beyond the period of maximum treatment; in such case, this should not happen without a previous re-evaluation, by the physician, of the patient conditions. -

The Emergence of New Psychoactive Substance (NPS) Benzodiazepines

Issue: Ir Med J; Vol 112; No. 7; P970 The Emergence of New Psychoactive Substance (NPS) Benzodiazepines. A Survey of their Prevalence in Opioid Substitution Patients using LC-MS S. Mc Namara, S. Stokes, J. Nolan HSE National Drug Treatment Centre Abstract Benzodiazepines have a wide range of clinical uses being among the most commonly prescribed medicines globally. The EU Early Warning System on new psychoactive substances (NPS) has over recent years detected new illicit benzodiazepines in Europe’s drug market1. Additional reference standards were obtained and a multi-residue LC- MS method was developed to test for 31 benzodiazepines or metabolites in urine including some new benzodiazepines which have been classified as New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) which comprise a range of substances, including synthetic cannabinoids, opioids, cathinones and benzodiazepines not covered by international drug controls. 200 urine samples from patients attending the HSE National Drug Treatment Centre (NDTC) who are monitored on a regular basis for drug and alcohol use and which tested positive for benzodiazepine class drugs by immunoassay screening were subjected to confirmatory analysis to determine what Benzodiazepine drugs were present and to see if etizolam or other new benzodiazepines are being used in the addiction population currently. Benzodiazepine prescription and use is common in the addiction population. Of significance we found evidence of consumption of an illicit new psychoactive benzodiazepine, Etizolam. Introduction Benzodiazepines are useful in the short-term treatment of anxiety and insomnia, and in managing alcohol withdrawal. 1 According to the EMCDDA report on the misuse of benzodiazepines among high-risk opioid users in Europe1, benzodiazepines, especially when injected, can prolong the intensity and duration of opioid effects. -

Endogenous Benzodiazepine-Like Compounds and Diazepam Binding Inhibitor in Serum of Patients Gut: First Published As 10.1136/Gut.42.6.861 on 1 June 1998

Gut 1998;42:861–867 861 Endogenous benzodiazepine-like compounds and diazepam binding inhibitor in serum of patients Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.42.6.861 on 1 June 1998. Downloaded from with liver cirrhosis with and without overt encephalopathy R Avallone, M L Zeneroli, I Venturini, L Corsi, P Schreier, M Kleinschnitz, C Ferrarese, F Farina, C Baraldi, N Pecora, M Frigo, M Baraldi Abstract The involvement of this receptor system in Background/Aim—Despite some contro- overt hepatic encephalopathy (OHE), discov- versy, it has been suggested that endog- ered in the 1980s during studies on GABAA enous benzodiazepine plays a role in the receptors in the brain of animals with OHE, pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. was considered likely when specific benzodi- The aim of the present study was to evalu- azepine receptor antagonists were shown to ate the concentrations of endogenous ben- revert the symptoms of encephalopathy in ani- zodiazepines and the peptide, diazepam mal models4 and in patients.56 Later, the binding inhibitor, in the blood of patients observation of an increased presence of endog- with liver cirrhosis with and without overt enous benzodiazepine receptor ligands (BZDs) encephalopathy, and to compare these in animals and patients with OHE7–13 suggested levels with those of consumers of com- that this phenomenon may contribute to the mercial benzodiazepines. enhancement of GABAergic neurotrans- 14 Subjects—Normal subjects (90), benzodi- mission. We cannot exclude, however, the azepine consumers (14), and cirrhotic possibility that compounds such as 1315 16 patients (113) were studied. ammonia or neurosteroids contribute to Methods—Endogenous benzodiazepines the above mentioned increased functional were measured by the radioligand binding activity of the GABAA receptor system. -

Schedules of Controlled Substances (.Pdf)

PURSUANT TO THE TEXAS CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ACT, HEALTH AND SAFETY CODE, CHAPTER 481, THESE SCHEDULES SUPERCEDE PREVIOUS SCHEDULES AND CONTAIN THE MOST CURRENT VERSION OF THE SCHEDULES OF ALL CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES FROM THE PREVIOUS SCHEDULES AND MODIFICATIONS. This annual publication of the Texas Schedules of Controlled Substances was signed by John Hellerstedt, M.D., Commissioner of Health, and will take effect 21 days following publication of this notice in the Texas Register. Changes to the schedules are designated by an asterisk (*). Additional information can be obtained by contacting the Department of State Health Services, Drugs and Medical Devices Unit, P.O. Box 149347, Austin, Texas 78714-9347. The telephone number is (512) 834-6755 and the website address is http://www.dshs.texas.gov/dmd. SCHEDULES Nomenclature: Controlled substances listed in these schedules are included by whatever official, common, usual, chemical, or trade name they may be designated. SCHEDULE I Schedule I consists of: -Schedule I opiates The following opiates, including their isomers, esters, ethers, salts, and salts of isomers, esters, and ethers, unless specifically excepted, if the existence of these isomers, esters, ethers, and salts are possible within the specific chemical designation: (1) Acetyl-α-methylfentanyl (N-[1-(1-methyl-2-phenethyl)-4-piperidinyl]-N- phenylacetamide); (2) Acetylmethadol; (3) Acetyl fentanyl (N-(1-phenethylpiperidin-4-yl)-N-phenylacetamide); (4) Acryl fentanyl (N-(1-phenethylpiperidin-4-yl)-N-phenylacrylamide) (Other name: -

A Review of the Evidence of Use and Harms of Novel Benzodiazepines

ACMD Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Novel Benzodiazepines A review of the evidence of use and harms of Novel Benzodiazepines April 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Legal control of benzodiazepines .......................................................................................... 4 3. Benzodiazepine chemistry and pharmacology .................................................................. 6 4. Benzodiazepine misuse............................................................................................................ 7 Benzodiazepine use with opioids ................................................................................................... 9 Social harms of benzodiazepine use .......................................................................................... 10 Suicide ............................................................................................................................................. 11 5. Prevalence and harm summaries of Novel Benzodiazepines ...................................... 11 1. Flualprazolam ......................................................................................................................... 11 2. Norfludiazepam ....................................................................................................................... 13 3. Flunitrazolam .......................................................................................................................... -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to the HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM GADOCOLETICUM 280776-87-6 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACAMPROSATE -

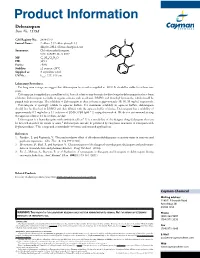

Download Product Insert (PDF)

Product Information Delorazepam Item No. 15938 CAS Registry No.: 2894-67-9 H O Formal Name: 7-chloro-5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,3- N dihydro-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one Synonyms: Chlordesmethyldiazepam, NSC 169895, Ro 5-3027 Cl N MF: C15H10Cl2N2O FW: 305.1 Purity: ≥98% Cl Stability: ≥2 years at -20°C Supplied as: A crystalline solid λ UV/Vis.: max: 227, 319 nm Laboratory Procedures For long term storage, we suggest that delorazepam be stored as supplied at -20°C. It should be stable for at least two years. Delorazepam is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the delorazepam in the solvent of choice. Delorazepam is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide, which should be purged with an inert gas. The solubility of Delorazepam in these solvents is approximately 10, 30, 30 mg/ml, respectively. Delorazepam is sparingly soluble in aqueous buffers. For maximum solubility in aqueous buffers, delorazepam should first be dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with the aqueous buffer of choice. Delorazepam has a solubility of approximately 0.5 mg/ml in a 1:1 solution of DMSO:PBS (pH 7.2) using this method. We do not recommend storing the aqueous solution for more than one day. Delorazepam is a benzodiazepine with anxiolytic effects.1 It is a metabolite of the designer drug diclazepam that can be detected in either the serum or urine.2 Delorazepam can also be produced by enzymatic treatment of lorazepam with β-glucuronidase.3 This compound is intended for forensic and research applications. -

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE EXERCISES (ICE) Summary Report

INTERNATIONAL QUALITY ASSURANCE PROGRAMME (IQAP) INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE EXERCISES (ICE) Summary Report BIOLOGICAL SPECIMENS 2017/1 INTERNATIONAL QUALITY ASSURANCE PROGRAMME (IQAP) INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE EXERCISES (ICE) Table of contents Introduction Page 2 Comments from the International Panel of Forensic Experts Page 2 NPS reported by ICE participants Page 4 Codes and Abbreviations Page 6 Sample 1 Analysis Page 7 Identified substances Page 7 Statement of findings Page 8 Identification methods Page 11 Summary Page 14 Sample 2 Analysis Page 15 Identified substances Page 15 Statement of findings Page 18 Identification methods Page 23 Summary Page 6 2 - Z Scores Page 27 Sample 3 Analysis Page 37 Identified substances Page 37 Statement of findings Page 39 Identification methods Page 44 Summary Page 47 Z- Scores Page 48 Sample 4 Analysis Page 51 Identified substances Page 51 Statement of findings Page 54 Identification methods Page 59 Summary Page 62 Z- Scores Page 63 Test Samples Information Samples Comments on samples Sample 1 BS-1 was a blank urine test sample containing no substances from the ICE menu. Sample 2 To prepare BS-2, urine was spiked with an aqueous solution of amfetamine sulphate (1270ng base/ml) and methanol solutions of nordazepam (1960ng base/ml), oxazepam (570ng/ml) and temazepam (580ng/ml). The spiked urine was dispensed in 50ml aliquots and lyophilised. Sample 3 To prepare BS-3, urine was spiked with an aqueous solution of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) (16560ng/ml). The spiked urine was dispensed in 50ml aliquots and lyophilised. Sample 4 To prepare BS-4, urine was spiked with an aqueous solution of morphine sulphate (860ng base/ml).