Lead the River to Kneel Before the Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Download Song List As

Top40/Current Bruno Mars 24K Magic Stronger (What Doesn't Kill Kelly Clarkson Treasure Bruno Mars You) Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Firework Katy Perry Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Hot N Cold Katy Perry Good as Hell Lizzo I Choose You Sara Bareilles Cake By The Ocean DNCE Till The World Ends Britney Spears Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Life is Better with You Michael Franti & Spearhead Don’t stop the music Rihanna Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti & Spearhead We Found Love Rihanna / Calvin Harris You Are The Best Thing Ray LaMontagne One Dance Drake Lovesong Adele Don't Start Now Dua Lipa Make you feel my love Adele Ride wit Me Nelly One and Only Adele Timber Pitbull/Ke$ha Crazy in Love Beyonce Perfect Ed Sheeran I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Let’s Get It Started Black Eyed Peas Cheap Thrills Sia Everything Michael Buble I Love It Icona Pop Dynomite Taio Cruz Die Young Kesha Crush Dave Matthews Band All of Me John Legend Where You Are Gavin DeGraw Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Forget You Cee Lo Green Party in the U.S.A. Miley Cyrus Feel So Close Calvin Harris Talk Dirty Jason Derulo Song for You Donny Hathaway Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen This Is How We Do It Montell Jordan Brokenhearted Karmin No One Alicia Keys Party Rock Anthem LMFAO Waiting For Tonight Jennifer Lopez Starships Nicki Minaj Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Don't Stop The Party Pitbull This Love Maroon 5 Happy Pharrell Williams I'm Yours Jason Mraz Domino Jessie J Lucky Jason Mraz Club Can’t Handle Me Flo Rida Hey Ya! OutKast Good Feeling -

Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. the Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. The Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli Relatore Ch. Prof. Marco Fazzini Correlatore Ch. Prof. Alessandro Scarsella Laureanda Irene Pozzobon Matricola 828267 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 ABSTRACT When a system of segregation tries to oppress individuals and peoples, struggle becomes an important part in order to have social and civil rights back. Revolutionary poem-songs are to be considered as part of that struggle. This dissertation aims at offering an overview on how South African poet-songwriters, in particular the white Roger Lucey and the black Mzwakhe Mbuli, composed poem-songs to fight against apartheid. A secondary purpose of this study is to show how, despite the different ethnicities of these poet-songwriters, similar themes are to be found in their literary works. In order to investigate this topic deeply, an interview with Roger Lucey was recorded and transcribed in September 2014. This work will first take into consideration poem-songs as part of a broader topic called ‘oral literature’. Secondly, it will focus on what revolutionary poem-songs are and it will report examples of poem-songs from the South African apartheid regime (1950s to 1990s). Its third part will explore both the personal and musical background of the two songwriters. Part four, then, will thematically analyse Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli’s lyrics composed in that particular moment of history. Finally, an epilogue will show how the two songwriters’ perspectives have evolved in the post-apartheid era. -

“What's Important in My Life” the Personal Goals and Values Card Sorting Task for Individuals with Schizophrenia Theresa B

“What’s Important in My Life” The Personal Goals and Values Card Sorting Task for Individuals with Schizophrenia Theresa B. Moyers and Steve Martino © 2006 Using Motivational Interviewing for clients with schizophrenia requires some adaptations of traditional methods, including the Personal Values Card Sorting Task. In our clinical work, we found that the original task described by Miller, C’de Baca, Matthews and Wilbourne (2001; casaa.unm.edu) was not useful for these clients because some of the values described on the cards were overly abstract (e.g., Autonomy, Mastery) and other issues of potential importance to these clients (e.g., Find medications that work for me, Stop hearing voices) were absent. Our modification of the Personal Goals and Values Card Sorting Task was originally developed as part of a small pilot study (Graeber et al., 2003) to investigate the impact of MI on the substance use of veterans with schizophrenia. We have significantly enlarged the current version and present it as a viable method for discussing important life goals and values with clients who struggle with schizophrenia. This tool is available for researchers and clinicians at no charge through the UNM CASAA website. Individuals wishing to use the cards can print them on business stock cards. Alternatively, they may be printed on labels and placed on index cards. They may not be sold, re-published or used for commercial purposes. The Card Sorting Task is relatively straightforward. Tell the client you will be using an exercise to help you figure out what is most important to him or her in life. -

UWS Academic Portal the Rock Band KISS and American Dream

UWS Academic Portal The Rock Band KISS and American Dream Ideology James, Kieran; Briggs, Susan P.; Grant, Bligh Published in: European Journal of American Culture DOI: 10.1386/ejac.37.1.19_1 Published: 01/03/2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication on the UWS Academic Portal Citation for published version (APA): James, K., Briggs, S. P., & Grant, B. (2018). The Rock Band KISS and American Dream Ideology. European Journal of American Culture, 37(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.1386/ejac.37.1.19_1 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UWS Academic Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 17 Sep 2019 “The Rock Band KISS and American Dream Ideology” by Kieran James* University of the West of Scotland [email protected] Susan P. Briggs University of South Australia [email protected] and Bligh Grant University Technology Sydney [email protected] *Address for Correspondence: Dr Kieran James, School of Business and Enterprise, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley campus, Paisley, Renfrewshire, PA12BE, Scotland, tel: +44 (0)141 848 3350, e-mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Acknowledgements We thank Frances Miley, Andrew Read, conference participants at the International Conference for Critical Accounting (ICCA), Baruch College, New York City, 28 April 2011, this journal’s two anonymous reviewers, and this journal’s Editor for helpful comments. -

TRACKLIST and SONG THEMES 1. Father

TRACKLIST and SONG THEMES 1. Father (Mindful Anthem) 2. Mindful on that Beat (Mindful Dancing) 3. MindfOuuuuul (Mindful Listening) 4. Offa Me (Respond Vs. React) 5. Estoy Presente (JG Lyrics) (Mindful Anthem) 6. (Breathe) In-n-Out (Mindful Breathing) 7. Love4Me (Heartfulness to Self) 8. Mindful Thinker (Mindful Thinking) 9. Hold (Anchor Spot) 10. Don't (Hold It In) (Mindful Emotions) 11. Gave Me Life (Gratitude & Heartfulness) 12. PFC (Brain Science) 13. Emotions Show Up (Jason Lyrics) (Mindful Emotions) 14. Thankful (Mindful Gratitude) 15. Mind Controlla (Non-Judgement) LYRICS: FATHER (Mindful Sits) Aneesa Strings HOOK: (You're the only power) Beautiful Morning, started out with my Mindful Sit Gotta keep it going, all day long and Beautiful Morning, started out with my Mindful Sit Gotta keep it going... I just wanna feel liberated I… I just wanna feel liberated I… If I ever instigated I am sorry Tell me who else here can relate? VERSE 1: If I say something heartful Trying to fill up her bucket and she replies with a put-down She's gon' empty my bucket I try to stay respectful Mindful breaths are so helpful She'll get under your skin if you let her But these mindful skills might help her She might not wanna talk about She might just wanna walk about it She might not even wanna say nothing But she know her body feel something Keep on moving till you feel nothing Remind her what she was angry for These yoga poses help for sure She know just what she want, she wanna wake up… HOOK MINDFUL ON THAT BEAT Coco Peila + Hazel Rose INTRO: Oh my God… Ms. -

BWTB Valentines LOVE Show 2016

1 All Love Show 2016 1 2 9AM The Beatles - It’s Only Love- Help! / INTRO : THE WORD (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John Recorded in six takes on June 15, 1965. The first Beatles song to include a reference to getting “high” (“I get high when I see you go by”). The working title prior to lyrics being written was “That’s a Nice Hat.” George Martin and his Orchestra recorded the instrumental version of “It’s Only Love” using the original title. In 1972 Lennon called “It’s Only Love” “the one song I really hate of mine.” On U.S. album: Rubber Soul - Capitol LP 2 3 The Beatles - Love Me Do – Please Please Me (McCartney-Lennon) Lead vocal: John and Paul The Beatles’ first single release for EMI’s Parlophone label. Released October 5, 1962, it reached #17 on the British charts. Principally written by Paul McCartney in 1958 and 1959. Recorded with three different drummers: Pete Best (June 6, 1962, EMI audition), Ringo Starr (September 4, 1962), and Andy White (September 11, 1962 with Ringo playing tambourine). The 45 rpm single lists the songwriters as Lennon-McCartney. One of several Beatles songs Paul McCartney owns with Yoko Ono. Starting with the songs recorded for their debut album on February 11, 1963, Lennon and McCartney’s output was attached to their Northern Songs publishing company. Because their first single was released before John and Paul had contracted with a music publisher, EMI assigned it to their own, a company called Ardmore and Beechwood, which took the two songs “Love Me Do” and “P.S. -

Gender Role Construction in the Beatles' Lyrics

“SHE LOVES YOU, YEAH, YEAH, YEAH!”: GENDER ROLE CONSTRUCTION IN THE BEATLES’ LYRICS Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magister der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Mario Kienzl am Institut für: Anglistik Begutachter: Ao.Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr.phil. Hugo Keiper Graz, April 2009 Danke Mama. Danke Papa. Danke Connie. Danke Werner. Danke Jenna. Danke Hugo. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 2. The Beatles: 1962 – 1970...................................................................................................... 6 3. The Beatles’ Rock and Roll Roots .................................................................................... 18 4. Love Me Do: A Roller Coaster of Adolescence and Love............................................... 26 5. Please Please Me: The Beatles Get the Girl ..................................................................... 31 6. The Beatles enter the Domestic Sphere............................................................................ 39 7. The Beatles Step Out.......................................................................................................... 52 8. Beatles on the Rocks........................................................................................................... 57 9. Do not Touch the Beatles.................................................................................................. -

Washington Journal of Modern China

Washington Journal of Modern China Fall 2012, Vol. 10, No. 2 20th Anniversary Issue (1992-2012) ISSN 1064-3028 Copyright, Academic Press of America, Inc. i Washington Journal of Modern China Fall 2012, Vol. 10, No. 2 20th Anniversary Issue (1992-2012) Published by the United States-China Policy Foundation Co-Editors Katie Xiao and Shannon Tiezzi Assistant Editor Amanda Watson Publisher/Founder Chi Wang, Ph.D. The Washington Journal of Modern China is a policy- oriented publication on modern Chinese culture, economics, history, politics, and United States-China relations. The views and opinions expressed in the journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foundation. The publishers, editors, and committee assume no responsibility for the statements of fact or opinion expressed by the contributors. The journal welcomes the submission of manuscripts and book reviews from scholars, policymakers, government officials, and other professionals on all aspects of modern China, including those that deal with Taiwan and Hong Kong, and from all points of view. We regret we are unable to return any materials that are submitted. Manuscript queries should be sent to the Editor, the Washington Journal of Modern China , The United States-China Policy Foundation, 316 Pennsylvania Avenue SE, Suites 201-202, Washington, DC 20003. Telephone: 202-547-8615. Fax: 202-547- 8853. The annual subscription rate for institutions is $40.00; for individuals, $30.00. Shipping and Handling is $5.00 per year. Back/sample issues are available for $14.00/issue. Subscription requests can be made online, at www.uscpf.org or sent to the address above. -

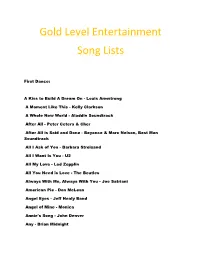

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

Innovators: Songwriters

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: SONGWRITERS David Galenson Working Paper 15511 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15511 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2009 The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2009 by David Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Songwriters David Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15511 November 2009 JEL No. N00 ABSTRACT Irving Berlin and Cole Porter were two of the great experimental songwriters of the Golden Era. They aimed to create songs that were clear and universal. Their ability to do this improved throughout much of their careers, as their skill in using language to create simple and poignant images improved with experience, and their greatest achievements came in their 40s and 50s. During the 1960s, Bob Dylan and the team of John Lennon and Paul McCartney created a conceptual revolution in popular music. Their goal was to express their own ideas and emotions in novel ways. Their creativity declined with age, as increasing experience produced habits of thought that destroyed their ability to formulate radical new departures from existing practices, so their most innovative contributions appeared early in their careers. -

A Geometric Analysis of the Harmonic Structure of in My Life

A GEOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF THE HARMONIC STRUCTURE OF IN MY LIFE JAMES S. WALKER AND GARY W. DON ABSTRACT. After our book [1] was published, we found a striking example of the impor- tance of the Tonnetz for analyzing the harmonic structure of The Beatles’ song, In My Life. Our Tonnetz analysis will illustrate the highly structured geometric logic underlying the numerous chord progressions in the song. Spectrograms provide a way for us to visualize chordal harmonics and their connection with voice leading. We shall also describe the in- teresting harmonic rhythms of the song’s chord progressions. A lot of this harmonic rhythm lends itself well to a geometric description. 1. INTRODUCTION The Beatles, especially in some classic songs of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, used much more elaborate chord progressions than one finds in typical popular songs. A fine example of this occurs with their song, In My Life. For whatever reason, the chord progressions and instrumental melodies found in various sheet musics for Lennon and McCartney songs, such as In My Life, are aural transcriptions made by others.1 This has led to some differences in the various sheet musics, and chord listings, that are available. Our approach to this difficulty is to do an initial analysis on a basic template for the song found in the lead sheet version in [2]. After analyzing its harmonic structure, consisting of a Tonnetz analysis of its chord progressions and an examination of its harmonic rhythm, we then look at a computer analysis of the recorded performance of In My Life from The Beatles’ album Rubber Soul.