The X-Men and the Metaphor for Approaches to Racial Equality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Kill Or Be Killed Volume 1 Pdf Ebook by Ed Brubaker

Download Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 pdf ebook by Ed Brubaker You're readind a review Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 ebook. To get able to download Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 Series: Kill or Be Killed 128 pages Publisher: Image Comics (January 24, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1534300287 ISBN-13: 978-1534300286 Product Dimensions:6.4 x 0.5 x 10 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 15503 kB Description: The bestselling team of ED BRUBAKER and SEAN PHILLIPS (THE FADE OUT, CRIMINAL, FATALE) return with KILL OR BE KILLED, the twisted story of a young man forced to kill bad people, and how he struggles to keep his secret from destroying his life.Both a thriller and a deconstruction of vigilantism, KILL OR BE KILLED is unlike anything BRUBAKER & PHILLIPS... Review: Finally found what Im looking for in a comic. The way this story is written makes you feel like it could actually happen (provided demons were real). Brubaker is really good at placing you in the head of the main character. I would recommend this to anyone who is into dark, gritty fantasies set in the modern world. The plot reminds me of the anime... Ebook File Tags: main character pdf, brubaker and phillips pdf, bad people pdf, looking forward pdf, sean phillips pdf, wait for volume pdf, comic book pdf, kill or be killed pdf, kill bad pdf, demon pdf, comics pdf, dylan pdf, liberal pdf, art pdf, dark pdf, protagonist pdf, vigilante pdf, artwork pdf, killing pdf, pages Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 pdf book by Ed Brubaker in pdf books Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 be killed 1 or volume pdf kill killed volume 1 be or fb2 killed kill or volume be 1 ebook 1 volume killed or kill be book Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 1 Volume or Be Kill Killed it's not worth the money. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

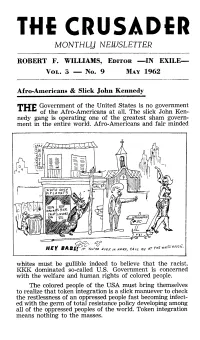

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

Ebook Free Marvel: Spider-Man 1000 Dot-To-Dot Book

Ebook Free Marvel: Spider-Man 1000 Dot-to-Dot Book Join your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man and all your favorite comic characters on a new adventure from best-selling dot-to-dot artist Thomas Pavitte. With 20 complex puzzles to complete, each consisting of at least 1,000 dots, Marvel fans will have hours of fun bringing Spidey and his friends, allies, and most villainous foes to life. Paperback: 48 pages Publisher: Thunder Bay Press; Act Csm edition (March 14, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1626867852 ISBN-13: 978-1626867857 Product Dimensions: 9.9 x 0.4 x 13.9 inches Shipping Weight: 14.4 ounces (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 5.0 out of 5 stars 2 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #405,918 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #101 in Books > Arts & Photography > Drawing > Coloring Books for Grown-Ups > Comics & Manga #254 in Books > Humor & Entertainment > Puzzles & Games > Board Games #696 in Books > Humor & Entertainment > Puzzles & Games > Puzzles Thomas Pavitte is a graphic designer and experimental artist who often uses simple techniques to create highly complex pieces. He set an unofficial record for the most complex dot-to-dot drawing in 2011 with his version of the Mona Lisa in 6,239 dots. He lives and works in Melbourne, Australia. Best dot-to-dot artist around. I love Thomas Pavitte's books...I've bought 5 of them. These are therapy for my overstressed head (I have twin 5 year olds) and also will turn into fun, inexpensive art on his walls. -

Runaway Pdf Free Download

RUNAWAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alice Munro | 368 pages | 03 May 2017 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099472254 | English | London, United Kingdom Runaway PDF Book Universal Conquest Wiki. Health Care for Women International. One of the most dramatic examples is the African long-tailed widowbird Euplectes progne ; the male possesses an extraordinarily long tail. Although a fight broke out, the X-Men accepted Molly's decision to remain with her friends, but also left the invitation open. Geoffrey Wilder 33 episodes, Our TV show goes beyond anything you have seen previously. First appearance. Entry 1 of 3 1 : one that runs away from danger, duty, or restraint : fugitive 2 : the act of running away out of control also : something such as a horse that is running out of control 3 : a one-sided or overwhelming victory runaway. How many sets of legs does a shrimp have? It is estimated that each year there are between 1. Send us feedback. In hopes to find a sense of purpose, Karolina started dabbling in super-heroics, [87] and was quickly joined by Nico. Metacritic Reviews. The Runaways outside the Malibu House. Added to Watchlist. Edit Did You Know? Sound Mix: Dolby Stereo. Runtime: 99 min. Bobby Ramsay Chris Mulkey We will share Japanese culture and travel, in a way that is exciting, entertaining and has never been done before! See also: Young night drifters and youth in Hong Kong. Company Credits. Miss Shields Carol Teesdale Episode 3 The Ultimate Detour. Hood in ," 24 Nov. Runaways have an elevated risk of destructive behavior. Alex Wilder 33 episodes, Yes No Report this. -

"Marvel's First Deaf Superhero" (PDF)

Lastname 1 Firstname Lastname English 102 Dr. Williams 28 February 2018 Marvel’s First Deaf Superhero In December of 1999, Marvel first introduced their first deaf superhero going by the name of Echo in the comic Daredevil Vol.2 #9. Echo or alias name Maya Lopez is a Native American born girl who was born with the disability of hearing loss. Later in her story her father is killed by Wilson Fisk also known as the Kingpin who was her fathers partner in crime. Fisk adopts his daughter and raises her into the woman she is now. But the way he raised her was actually training her in order to counter and defeat the superhero the Daredevil, another superhero with a disability of blindness. Later on in the story she finds love with a man named Matt Murdock, a blind man who later in the story she finds out that he is the Daredevil and the man she loves. She finally realizes the lies she grew up with and summons hatred and defeats her adopted father the Kingpin. She then later becomes fond with Wolverine and adopts a new identity as a superhero named Ronin. The way Marvel employs their inspiration porn from the character Echo is by using her as a super crip in order to inspire and create a role model for kids and adults with disabilities all over the world and in the Marvel Universe. Superheroes with disabilities are often given other heightened senses and abilities if they are lacking one, which Echo is capable of. Echo is capable of seeing very clearly and even reading lips from videos or in person in which she can transcribe every conversation as if she could hear the whole conversation. -

Cvr a Andrea Sorrentino (Mr) $5.99 Aug21 7002 Batman the Imposter #1 (Of 3) Cvr B Lee Bermejo Var (Mr) $5.99

DC ENTERTAINMENT AUG21 7001 BATMAN THE IMPOSTER #1 (OF 3) CVR A ANDREA SORRENTINO (MR) $5.99 AUG21 7002 BATMAN THE IMPOSTER #1 (OF 3) CVR B LEE BERMEJO VAR (MR) $5.99 AUG21 7004 BATMAN #114 CVR A JORGE JIMENEZ (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7005 BATMAN #114 CVR B JORGE MOLINA CARD STORK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7007 BATMAN #115 CVR A JORGE JIMENEZ (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7008 BATMAN #115 CVR B JORGE MOLINA CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7010 ARKHAM CITY THE ORDER OF THE WORLD #1 (OF 6) CVR A SAM WOLFE CONNELLY $3.99 AUG21 7011 ARKHAM CITY THE ORDER OF THE WORLD #1 (OF 6) CVR B FRANCESCO MATTINA CARD STOCK VAR $4.99 AUG21 7013 BATMAN SECRET FILES PEACEKEEPER-01 #1 (ONE SHOT) CVR A RAFAEL SARMENTO (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7014 BATMAN SECRET FILES PEACEKEEPER-01 #1 (ONE SHOT) CVR B TYLER KIRKHAM CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7016 CATWOMAN #36 CVR A YANICK PAQUETTE (FEAR STATE) $3.99 AUG21 7017 CATWOMAN #36 CVR B JENNY FRISON CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7018 NIGHTWING #85 CVR A BRUNO REDONDO (FEAR STATE) $3.99 AUG21 7019 NIGHTWING #85 CVR B JAMAL CAMPBELL CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7020 DETECTIVE COMICS #1044 CVR A DAN MORA (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7021 DETECTIVE COMICS #1044 CVR B LEE BERMEJO CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $5.99 AUG21 7022 I AM BATMAN #2 CVR A OLIVIER COIPEL (FEAR STATE) $3.99 AUG21 7023 I AM BATMAN #2 CVR B FRANCESCO MATTINA CARD STOCK VAR (FEAR STATE) $4.99 AUG21 7024 BATMAN URBAN LEGENDS #8 CVR A COLLEEN DORAN (FEAR STATE) $7.99 AUG21 7025 BATMAN URBAN LEGENDS #8 CVR B KHARY RANDOLPH -

Graphic No Vels & Comics

GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS SPRING 2020 TITLE Description FRONT COVER X-Men, Vol. 1 The X-Men find themselves in a whole new world of possibility…and things have never been better! Mastermind Jonathan Hickman and superstar artist Leinil Francis Yu reveal the saga of Cyclops and his hand-picked squad of mutant powerhouses. Collects #1-6. 9781302919818 | $17.99 PB Marvel Fallen Angels, Vol. 1 Psylocke finds herself in the new world of Mutantkind, unsure of her place in it. But when a face from her past returns only to be killed, she seeks vengeance. Collects Fallen Angels (2019) #1-6. 9781302919900 | $17.99 PB Marvel Wolverine: The Daughter of Wolverine Wolverine stars in a story that stretches across the decades beginning in the 1940s. Who is the young woman he’s fated to meet over and over again? Collects material from Marvel Comics Presents (2019) #1-9. 9781302918361 | $15.99 PB Marvel 4 Graphic Novels & Comics X-Force, Vol. 1 X-Force is the CIA of the mutant world—half intelligence branch, half special ops. In a perfect world, there would be no need for an X-Force. We’re not there…yet. Collects #1-6. 9781302919887 | $17.99 PB Marvel New Mutants, Vol. 1 The classic New Mutants (Sunspot, Wolfsbane, Mirage, Karma, Magik, and Cypher) join a few new friends (Chamber, Mondo) to seek out their missing member and go on a mission alongside the Starjammers! Collects #1-6. 9781302919924 | $17.99 PB Marvel Excalibur, Vol. 1 It’s a new era for mutantkind as a new Captain Britain holds the amulet, fighting for her Kingdom of Avalon with her Excalibur at her side—Rogue, Gambit, Rictor, Jubilee…and Apocalypse. -

The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie

DOI: 10.24843/JH.2018.v22.i03.p30 ISSN: 2302-920X Jurnal Humanis, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Unud Vol 22.3 Agustus 2018: 771-780 The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie Ni Putu Ayu Mitha Hapsari1*, I Nyoman Tri Ediwan2, Ni Luh Nyoman Seri Malini3 [123]English Department - Faculty of Arts - Udayana University 1[[email protected]] 2[[email protected]] 3[[email protected]] *Corresponding Author Abstract The title of this paper is The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. This study focuses on categorization and function of the characters in the movie and conflicts in the main character (external and internal conflicts). The data of this study were taken from a movie entitled Doctor Strange. The data were collected through documentation method. In analyzing the data, the study used qualitative method. The categorization and function were analyzed based on the theory proposed by Wellek and Warren (1955:227), supported by the theory of literature proposed by Kathleen Morner (1991:31). The conflict was analyzed based on the theory of literature proposed by Kenney (1966:5). The findings show that the categorization and function of the characters in the movie are as follows: Stephen Strange (dynamic protagonist character), Kaecilius (static antagonist character). Secondary characters are The Ancient One (static protagonist character), Mordo (static protagonist character) and Christine (dynamic protagonist character). The supporting character is Wong (static protagonist character). Then there are two types of conflicts found in this movie, internal and external conflicts. Keywords: Character, Conflict, Doctor Strange. Abstrak Judul penelitian ini adalah The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. -

Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women's Lib”

Wonder Woman Wears Pants: Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women’s Lib” Issue Ann Matsuuchi Envisioning the comic book superhero Wonder Woman as a feminist activist defending a women’s clinic from pro-life villains at first seems to be the kind of story found only in fan art, not in the pages of the canonical series itself. Such a radical character reworking did not seem so outlandish in the American cultural landscape of the early 1970s. What the word “woman” meant in ordinary life was undergoing unprecedented change. It is no surprise that the iconic image of a female superhero, physically and intellectually superior to the men she rescues and punishes, would be claimed by real-life activists like Gloria Steinem. In the following essay I will discuss the historical development of the character and relate it to her presentation during this pivotal era in second wave feminism. A six issue story culminating in a reproductive rights battle waged by Wonder Woman- as-ordinary-woman-in-pants was unfortunately never realised and has remained largely forgotten due to conflicting accounts and the tangled politics of the publishing world. The following account of the only published issue of this story arc, the 1972 Women’s Lib issue of Wonder Woman, will demonstrate how looking at mainstream comic books directly has much to recommend it to readers interested in popular representations of gender and feminism. Wonder Woman is an iconic comic book superhero, first created not as a female counterpart to a male superhero, but as an independent, title- COLLOQUY text theory critique 24 (2012). -

Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? 2019

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Tomáš Lukáč Deadpool – Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Tomáš Lukáč 2 I would like to thank everyone who helped to bring this thesis to life, mainly to my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his patience, as well as to my parents, whose patience exceeded all reasonable expectations. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………...6 Tricksters across Cultures and How to Find Them ........................................................... 8 Loki and His Role in Norse Mythology .......................................................................... 21 Character of Deadpool .................................................................................................... 34 Comic Book History ................................................................................................... 34 History of the Character .............................................................................................. 35 Comic Book Deadpool ................................................................................................ 36 Films ............................................................................................................................ 43 Deadpool (2016)