Yemen the Continuing Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Arms in the Yemen War

\ POLICY BRIEF 2 \ 2019 German arms in the Yemen war For a comprehensive arms embargo against the war coalition Marius Bales \ BICC Max M. Mutschler \ BICC Policy recommendations \ A comprehensive arms embargo \ "Coalition of the willing" for an arms In view of the flagrant violation of international humani- embargo at EU level tarian law by the countries involved in the Yemen war, The German government must adopt the European export moratoria of limited duration, such as the current Parliament's demand that no more military equipment German ban on arms exports to Saudi Arabia until 30 be supplied to Saudi Arabia, expand it to include the March, are not sufficient. Because of the active participa- United Arab Emirates and actively support it within the tion of other countries in the air raids, the naval blockade European Union. in the Red Sea and the transfer of arms toYemeni militias, the German government must decide on a comprehen- \ Stop munitions deliveries by defence sive arms embargo that is not limited in time against all companies with German participation countries of the Saudi-led coalition. The German government must exert pressure on Rheinmetall to stop further deliveries of ammunition \ Revoke existing licenses by its foreign subsidiaries and joint ventures to the Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Bahrain, countries of the war coalition. Kuwait, Jordan, Sudan and Senegal are militarily directly involved in the Yemen war either through their partici- \ Increase international pressure on pation in the air raids, the naval blockade or through Gulf Monarchies the deployment of land forces. All of them therefore The federal government must use diplomatic channels must not receive any military equipment from Germany to demand information from Saudi Arabia and the UAE until further notice. -

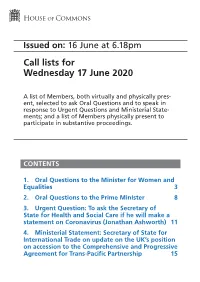

Call List for Wed 17 Jun 2020

Issued on: 16 June at 6.18pm Call lists for Wednesday 17 June 2020 A list of Members, both virtually and physically pres- ent, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial State- ments; and a list of Members physically present to participate in substantive proceedings. CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Minister for Women and Equalities 3 2. Oral Questions to the Prime MinIster 8 3. Urgent Question: To ask the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care if he will make a statement on Coronavirus (Jonathan Ashworth) 11 4. Ministerial Statement: Secretary of State for International Trade on update on the UK’s position on accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership 15 2 Call lists for Wednesday 17 June 2020 5. Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Bill [Lords]: Committee of the whole House 18 6. Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Bill [Lords]: Third Reading 20 Call lists for Wednesday 17 June 2020 3 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES After prayers Order Member Question Party Vir- Minister tual/ replying Physi- cal 1 Theresa Villi- What steps the Con Phys- Minister ers (Chipping Government is ical Scully Barnet) taking to support self-employed women during the covid-19 out- break. 2 + 3 Ruth Cadbury What steps she Lab Phys- Minister (Brentford and has taken in ical Badenoch Isleworth) response to the findings on the risks of covid-19 for BAME people in Public Health England's report entitled COVID- 19: review of disparities in risks and outcomes, published in June 2020. -

Cluster Weapons – Military Utility and Alternatives

FFI-rapport/2007/02345 Cluster weapons – military utility and alternatives Ove Dullum Forsvarets forskningsinstitutt/Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) 1 February 2008 FFI-rapport 2007/02345 Oppdrag 351301 ISBN 978-82-464-1318-1 Keywords Militære operasjoner / Military operations Artilleri / Artillery Flybomber / Aircraft bombs Klasevåpen / Cluster weapons Ammunisjon / Ammunition Approved by Ove Dullum Project manager Jan Ivar Botnan Director of Research Jan Ivar Botnan Director 2 FFI-rapport/2007/02345 English summary This report is made through the sponsorship of the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its purpose is to get an overview of the military utility of cluster munitions, and to find to which degree their capacity can be substituted by current conventional weapons or weapons that are on the verge of becoming available. Cluster munition roughly serve three purposes; firstly to defeat soft targets, i e personnel; secondly to defeat armoured of light armoured vehicles; and thirdly to contribute to the suppressive effect, i e to avoid enemy forces to use their weapons without inflicting too much damage upon them. The report seeks to quantify the effect of such munitions and to compare this effect with that of conventional weapons and more modern weapons. The report discusses in some detail how such weapons work and which effect they have against different targets. The fragment effect is the most important one. Other effects are the armour piercing effect, the blast effect, and the incendiary effect. Quantitative descriptions of such effects are usually only found in classified literature. However, this report is exclusively based on unclassified sources. The availability of such sources has been sufficient to get an adequate picture of the effect of such weapons. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Friday Volume 637 16 March 2018 No. 112 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Friday 16 March 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1113 16 MARCH 2018 1114 De Cordova, Marsha McDonald, Stuart C. House of Commons Debbonaire, Thangam Merriman, Huw Dinenage, Caroline Milling, Amanda Docherty-Hughes, Martin Monaghan, Carol Friday 16 March 2018 Dodds, Anneliese Morris, David Donelan, Michelle Morton, Wendy The House met at half-past Nine o’clock Dowden, Oliver Nandy, Lisa Duffield, Rosie Neill, Robert Edwards, Jonathan Newlands, Gavin PRAYERS Ellman, Mrs Louise Nokes, rh Caroline Farron, Tim O’Hara, Brendan Field, rh Mark Owen, Albert [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Fletcher, Colleen Pennycook, Matthew Foster, Kevin Philp, Chris 9.34 am Foxcroft, Vicky Pincher, Christopher Freer, Mike Pollard, Luke Patrick Grady (Glasgow North) (SNP): I beg to Furniss, Gill Pound, Stephen move, That the House sit in private. Gaffney, Hugh Pow, Rebecca Question put forthwith (Standing Order No. 163). Gardiner, Barry Pursglove, Tom The House proceeded to a Division. Gethins, Stephen Quin, Jeremy Gibb, rh Nick Reeves, Ellie Gibson, Patricia Robinson, Mary Mr Speaker: Will the Serjeant at Arms please investigate Grady, Patrick Saville Roberts, Liz the delay in the Aye Lobby, which I have reason to Grant, Peter Shelbrooke, Alec believe is not heavily populated? Green, Chris Sheppard, -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

CIG Template

Country Information and Guidance Yemen: Security and humanitarian situation Version 2.0 April 2016 Preface This document provides country of origin information (COI) and guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve the guidance and information we provide. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this document, please e-mail us. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard Record of the Entire Day in PDF Format. PDF File, 0.52

Friday Volume 630 3 November 2017 No. 46 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Friday 3 November 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1087 3 NOVEMBER 2017 1088 Gaffney, Hugh Murray, Mrs Sheryll House of Commons Gardiner, Barry Norris, Alex George, Ruth Onwurah, Chi Friday 3 November 2017 Goodwill, Mr Robert Opperman, Guy Graham, Luke Owen, Albert The House met at half-past Nine o’clock Gwynne, Andrew Peacock, Stephanie Haigh, Louise Pennycook, Matthew PRAYERS Hamilton, Fabian Phillips, Jess Hanson, rh David Pidcock, Laura Harrington, Richard Pincher, Christopher [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Harris, Carolyn Pollard, Luke Gareth Snell (Stoke-on-Trent Central) (Lab/Co-op): Harris, Rebecca Prentis, Victoria I beg to move, That the House sit in private. Hayman, Sue Pursglove, Tom Question put forthwith (Standing Order No. 163). Heappey, James Quince, Will Heaton-Harris, Chris Reed, Mr Steve The House proceeded to a Division. Hobhouse, Wera Reeves, Ellie Mr Speaker: I ask the Serjeant at Arms to investigate Hollobone, Mr Philip Reynolds, Jonathan the delay in the No lobby. Huq, Dr Rupa Rimmer, Ms Marie Hurd, Mr Nick Rutley, David The House having divided: Ayes 0, Noes 120. Jarvis, Dan Skidmore, Chris Division No. 32] [9.34 am Jenkin, Mr Bernard Smith, Cat Jones, Andrew Smith, Jeff AYES Jones, Darren Stephenson, Andrew Tellers for the Ayes: Jones, Gerald -

Her Majesty's Government and Her Official Opposition

Her Majesty’s Government and Her Official Opposition The Prime Minister and Leader of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP || Leader of the Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury (Chief Whip). He will attend Cabinet Rt Hon Mark Spencer MP remains || Nicholas Brown MP Treasurer of HM Household (Deputy Chief Whip) Stuart Andrew MP appointed Vice Chamberlain of HM Household (Government Whip) Marcus Jones MP appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP appointed || John McDonnell MP Chief Secretary to the Treasury - Cabinet Attendee Rt Hon Stephen Barclay appointed || Peter Dowd MP Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury Kemi Badenoch MP appointed Paymaster General in the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Minister for the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Michael Gove MP remains Minister of State in the Cabinet Office Chloe Smith MP appointed || Christian Matheson MP Secretary of State for the Home Department Rt Hon Priti Patel MP remains || Diane Abbott MP Minister of State in the Home Office Rt Hon James Brokenshire MP appointed Minister of State in the Home Office Kit Malthouse MP remains Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in the Home Office Chris Philp MP appointed Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and First Secretary of State Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP remains || Emily Thornberry MP Minister of State in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Rt Hon James Cleverly MP appointed Minister of State in the Foreign -

Introduction to Staff Register

REGISTER OF INTERESTS OF MEMBERS’ SECRETARIES AND RESEARCH ASSISTANTS (As at 15 October 2020) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register In accordance with Resolutions made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985 and 28 June 1993, holders of photo-identity passes as Members’ secretaries or research assistants are in essence required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £410 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass. Any gift (eg jewellery) or benefit (eg hospitality, services) that you receive, if the gift or benefit in any way relates to or arises from your work in Parliament and its value exceeds £410 in the course of a calendar year.’ In Section 1 of the Register entries are listed alphabetically according to the staff member’s surname. Section 2 contains exactly the same information but entries are instead listed according to the sponsoring Member’s name. Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. -

Operation Decisive Storm

ﻣﻮﺳﻮﻋﺔ اﻟﻤﺤﻴﻂ .ﻣﻨﺼﺔ إﻟﺘﺮوﻧﻴﺔ ﻟﻨﺸﺮ اﻟﻤﻠﻔﺎت اﻟﺮﻗﻤﻴﺔ واﻟﻤﻘﺎﻻت اﻟﻤﻮﺳﻮﻋﻴﺔ، ﺑﺎﻟﺘﻌﺎون ﻣﻊ اﻟﻤﺴﺘﺨﺪﻣﻴﻦ OPERATION DECISIVE STORM أﻛﺘﻮﺑﺮ Posted on 2017 ,21 Category: English ALMOHEET: ﺑﻮاﺳﻄﺔ Saudi Arabia deployed 150,000 soldiers, 100 fighter jets and navy units in Yemen after Hadi pleaded with its Gulf ally for help against the Houthi rebels, who were advancing toward the southern city of Aden, where Hadi is based, to remove him from power in an .attempted coup Who took part in the operation With the exception of Oman, members of the Gulf States joined Saudi Arabia with its aerial bombardment of the Houthis. The UAE contributed with 30 fighter jets, Bahrain 15, Kuwait 15, Qatar 10. Non-Gulf states have also showed their support to “Operation Decisive ”.Storm Operation Decisive Storm Page: 1 https://almoheet.net/operation-decisive-storm/ ﻣﻮﺳﻮﻋﺔ اﻟﻤﺤﻴﻂ .ﻣﻨﺼﺔ إﻟﺘﺮوﻧﻴﺔ ﻟﻨﺸﺮ اﻟﻤﻠﻔﺎت اﻟﺮﻗﻤﻴﺔ واﻟﻤﻘﺎﻻت اﻟﻤﻮﺳﻮﻋﻴﺔ، ﺑﺎﻟﺘﻌﺎون ﻣﻊ اﻟﻤﺴﺘﺨﺪﻣﻴﻦ Jordan deployed six fighter jets, Morocco, who expressed “complete solidarity” to Saudi Arabia provided six fighter jets while Sudan supplied three. An army media site confirmed that Sudan took part in the Saudi-led military operation Also, Egypt confirmed it will join .the Saudi-led coalition The Western-backed Syrian National Coalition opposition group also said it backed the Saudi operation and voiced its support to Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi as Yemen’s .“legitimate” leader In addition to the Arab states support, U.S. President authorized the provision of logistical ”.and intelligence support to “Decisive Storm When? .The operation was declared over on 26 Mar 2015 Air campaign The coalition declared Yemeni airspace to be a restricted area, with King Salman declaring the RSAF to be in full control of the zone. -

Of Those Who Pledged, 43 Were Elected As

First name Last name Full name Constituency Party Rosena Allin-Khan Rosena Allin-Khan Tooting Labour Fleur Anderson Fleur Anderson Putney Labour Tonia Antoniazzi Tonia Antoniazzi Gower Labour Ben Bradshaw Ben Bradshaw Exeter Labour Graham Brady Graham Brady Altrincham and Sale West Conservative Nicholas Brown Nicholas Brown Newcastle upon Tyne East Labour Wendy Chamberlain Wendy Chamberlain North East Fife Lib Dem Angela Crawley Angela Crawley Lanark and Hamilton East SNP Edward Davey Edward Davey Kingston and Surbiton Lib Dem Florence Eshalomi Florence Eshalomi Vauxhall Labour Tim Farron Tim Farron Westmorland and Lonsdale Lib Dem Simon Fell Simon Fell Barrow and Furness Conservative Yvonne Fovargue Yvonne Fovargue Makerfield Labour Mary Foy Mary Foy City Of Durham Labour Kate Green Kate Green Stretford and Urmston Labour Fabian Hamilton Fabian Hamilton Leeds North East Labour Helen Hayes Helen Hayes Dulwich and West Norwood Labour Dan Jarvis Dan Jarvis Barnsley Central Labour Clive Lewis Clive Lewis Norwich South Labour Caroline Lucas Caroline Lucas Brighton, Pavilion Green Justin Madders Justin Madders Ellesmere Port and Neston Labour Kerry McCarthy Kerry McCarthy Bristol East Labour Layla Moran Layla Moran Oxford West and Abingdon Lib Dem Penny Mordaunt Penny Mordaunt Portsmouth North Conservative Jessica Morden Jessica Morden Newport East Labour Stephen Morgan Stephen Morgan Portsmouth South Labour Ian Murray Ian Murray Edinburgh South Labour Yasmin Qureshi Yasmin Qureshi Bolton South East Labour Jonathan Reynolds Jonathan Reynolds