Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Council on the Humanities Minutes, No. 11-15

Office of th8 General Counsel N ational Foundation on the Aria and the Humanities MINUTES OF THE ELEVENTH MEETING OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE HUMANITIES Held Monday and Tuesday, February 17-18, 1969 U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. Members present; Barnaby C. Keeney, Chairman Henry Haskell Jacob Avshalomov Mathilde Krim Edmund F. Ball Henry Allen Moe Robert T. Bower James Wm. Morgan *Germaine Br&e Ieoh Ming Pei Gerald F. Else Emmette W. Redford Emily Genauer Robert Ward Allan A. Glatthorn Alfred Wilhelmi Members absent: Kenneth B. Clark Charles E. Odegaard John M. Ehle Walter J. Ong Paul G. Horgan Eugene B. Power Albert William Levi John P. Roche Soia Mentschikoff Stephen J. Wright James Cuff O'Brien *Present Monday only - 2 - Guests present: *Mr. Harold Arberg, director, Arts and Humanities Program, U. S. Office of Education Dr. William Emerson, assistant to the president, Hollins College, Virginia Staff members present; Dr. James H. Blessing, director, Division of Fellowships and Stipends, and acting director, Division of Research and Publication, National Endowment for the Humanities Dr. S. Sydney Bradford, program officer, Division of Research and Publication, NEH Miss Kathleen Brady, director, Office of Grants, NEH Mr. C. Jack Conyers, director, Office of Planning and Analysis, NEH Mr. Wallace B. Edgerton, deputy chairman, NEH Mr. Gerald George, special assistant to the chairman, NEH Dr. Richard Hedrich, Director of Public Programs, NEH Dr. Herbert McArthur, Director of Education Programs, NEH Miss Nancy McCall, research assistant, Office of Planning and Analysis, NEH Mr. Richard McCarthy, assistant to the director, Office of Planning and Analysis, NEH Miss Laura Olson, Public Information Officer, NEH Dr. -

Of the Friends' Historical Society

THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME FORTY-THREE NUMBER ONE 1951 FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRIENDS HOUSE, EUSTON ROAD, LONDON, N.W.i also obtainable at Friends Book Store 303 Arch Street, Philadelphia 6, Pa, U.S.A. Price 55. Yearly IDS. IMPORTANT NOTICE i The present membership^ of the Friends' Historical Society1 does not provide sufficient income to enable the Society to do its work as effectively as it desires. • Documents and articles of historical interest remain unpublished, and at least 50 more annual subscriptions are needed. The Committee therefore appeals to members and other: interested to: (1) Secure new subscribers. (2) Pay i os. for the Journal to be sent as a gift to someone. (3) Pay a larger annual subscription than the present minimum of i os. (4) Send a donation independent of the subscription. i The Society does important and valuable work, but it can only continue to do so if it is supplied with more funds. i Contributions should be sent to the Secretary, Friends House. ISABEL ROSS, ALFRED B. SEARLE, President. Chairman of Committee. Contents PAGE Presidential Address A. R. Barclay MSS., LXXII to LXXIX Quakerism in Friedrichstadt. Henry J. Cadbury Additions to the Library 22 John Bright and the " State of the Society " in 1851 Early Dictionary References to Quakers. Russell S. v Mortimer 29 Notes and Queries 35 I I Recent Publications .. 39 Vol. XLIII No. i 1951 THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY Publishing Office: Friends House, Euston Road, London, N.W.I Communications should be addressed to the Editor at Friends House. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

Adeline Mowbray, Or, the Bitter Acceptance of Woman’S Fate

Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 23 (2010): 187-211 Adeline Mowbray, or, the Bitter Acceptance of Woman’s Fate Aída Díaz Bild University of La Laguna [email protected] ABSTRACT Eighteenth-century women writers believed that the novel was the best vehicle to educate women and offer them a true picture of their lives and “wrongs”. Adelina Mowbray is the result of Opie’s desire to fulfil this important task. Opie does not try to offer her female readers alternatives to their present predicament or an idealized future, but makes them aware of the fact that the only ones who get victimized in a patriarchal system are always the powerless, that is to say, women. She gives us a dark image of the vulnerability of married women and points out not only how uncommon the ideal of companionate marriage was in real life, but also the difficulty of finding the appropriate partner for an egalitarian relationship. Lastly, she shows that there is now social forgiveness for those who transgress the established boundaries, which becomes obvious in the attitude of two of the most compassionate and generous characters of the novel, Rachel Pemberton and Emma Douglas, towards Adelina. Amelia Opie was one of the most popular and celebrated authors during the 1800s and 1810s, whose techniques and themes reveal her to be a representative woman novelist of her time. Unfortunately, her achievements were eclipsed by those of Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, Charles Dickens or the Brontës, and for a long time her work remained entirely forgotten. However, in the last years there has been a growing interest to recover and reappraise her novels and poems, trying to establish links between Opie and other late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century women writers. -

No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: the Nineteenth-Century Jewish

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1997 No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot Mary A. Linderman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linderman, Mary A., "No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot" (1997). Dissertations. 3684. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3684 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1997 Mary A. Linderman LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO "NO LONGER AN ALIEN, THE ENGLISH JEW": THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY JEWISH READER AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE JEW IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN DISRAELI, MATTHEW ARNOLD, AND GEORGE ELIOT VOLUME I (CHAPTERS I-VI) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY MARY A. LINDERMAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY 1997 Copyright by Mary A. Linderman, 1997 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the invaluable services of Dr. Micael Clarke as my dissertation director, and Dr. -

The Transition to Democracy in Victorian England

TRYGVE R. THOLFSEN THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY IN VICTORIAN ENGLAND I "The organization and the establishment of democracy in Christen- dom", de Tocqueville wrote in 1835, "is the great political problem of the time." 1 Nowhere was the problem more urgent than in England, whose industrial towns were soon to be torn by intense class conflict. Yet England resolved the tensions of the 1830's and i84o's, and went on to build a tough and supple political democracy in a massively undemocratic society. How did England become a democracy? The question has received little explicit attention from historians. Implicit in most narrative accounts of Victorian politics, however, is an answer of this sort: in response to outside pressure Parliament passed the reform bills that gradually democratized a long established system of representative government. Although this interpretive formula is unexceptionable up to a point, it conveys the impression that England became a democracy primarily as a result of statutory changes in the electoral system, whereas in fact the historical process involved was a good deal more complex. This exploratory essay is intended as a preliminary inquiry into the nature of that process. Extending the franchise to the working classes was the nub of the problem of democracy in England. As Disraeli remarked to Bright in March, 1867, "The Working Class Question is the real question, and that is the thing that demands to be settled." 2 The franchise issue was not exclusively political, however, but an expression of a much larger and more complicated problem of class relations. As a result of rapid industrialization, England in the middle third of the nineteenth century had to devise arrangements that would enable the middle and working classes of the industrial towns to live together peacefully on terms they 1 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, edited with an introduction by Henry Steele Commager (New York 1947), p. -

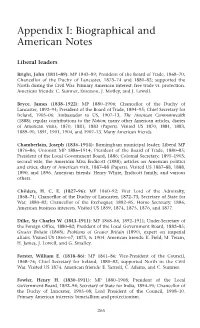

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes Liberal leaders Bright, John (1811–89): MP 1843–89; President of the Board of Trade, 1868–70; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1873–74 and 1880–82; supported the North during the Civil War. Primary American interest: free trade vs. protection. American friends: C. Sumner, Emerson, J. Motley, and J. Lowell. Bryce, James (1838–1922): MP 1880–1906; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1892–94; President of the Board of Trade, 1894–95; Chief Secretary for Ireland, 1905–06; Ambassador to US, 1907–13; The American Commonwealth (1888); regular contributions to the Nation; many other American articles, diaries of American visits, 1870, 1881, 1883 (Papers). Visited US 1870, 1881, 1883, 1889–90, 1891, 1901, 1904, and 1907–13. Many American friends. Chamberlain, Joseph (1836–1914): Birmingham municipal leader; Liberal MP 1876–86; Unionist MP 1886–1914; President of the Board of Trade, 1880–85; President of the Local Government Board, 1886; Colonial Secretary, 1895–1903; second wife, the American Miss Endicott (1888); articles on American politics and cities; diary of American visit, 1887–88 (Papers). Visited US 1887–88, 1888, 1890, and 1896. American friends: Henry White, Endicott family, and various others. Childers, H. C. E. (1827–96): MP 1860–92; First Lord of the Admiralty, 1868–71; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1872–73; Secretary of State for War, 1880–82; Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1882–85; Home Secretary, 1886; American business interests. Visited US 1859, 1874, 1875, 1876, and 1877. Dilke, Sir Charles W. (1843–1911): MP 1868–86, 1892–1911; Under-Secretary of the Foreign Office, 1880–82; President of the Local Government Board, 1882–85; Greater Britain (1868); Problems of Greater Britain (1890); expert on imperial affairs. -

Lord Rosebery and the Imperial Federation League, 1884-1893

Lord Rosebery and the Imperial Federation League, 1884-1893 BETWEEN 1884 and 1893 the Imperial Federation League flourished in Great Britain as the most important popular expression of the idea of closer imperial union between the mother country and her white self- governing colonies. Appearing as the result of an inaugural conference held at the Westminster Palace Hotel, London in July 1884,' the new League was pledged to 'secure by Federation the permanent unity of the Empire'2 and offered membership to any British subject who paid the annual registration fee of one shilling. As an avowedly propagandist organization, the League's plan of campaign included publications, lec- tures, meetings and the collection and dissemination of information and statistics about the empire, and in January 1886 the monthly journal Imperial Federation first appeared as a regular periodical monitoring League progress and events until the organization's abrupt collapse in December 1893. If the success of the foundation conference of July 1884 is to be measured in terms of the number of important public figures who attend- ed and who were willing to lend their names and influence to the move- ment for closer imperial union, then the meeting met with almost unqualified approval. When W.E. Forster addressed the opening con- ference as the chairman on 29 July 1884,3 the assembled company iry:lud- ed prominent politicians from both Liberal and Conservative parties in Great Britain, established political figures from the colonies, and a host of colonists and colonial expatriates who were animated by a great imperial vision which seemed to offer security and prosperity, both to the the mother country and to the colonies, in a world of increasing economic depression and foreign rivalry." Apart from the dedicated 1 Report of the Westminister Palace Hotel Conference, 29 July 1884, London, 1884, Rhodes House Library, Oxford. -

Memoir of Amelia Opie

' • ; ,: mmff^fffiKiiJiM mm —-rt FROM THE LIBRARY OF REV. LOUIS FITZGERALD BENSON, D. D BEQUEATHED BY HIM TO THE LIBRARY OF PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY — : Amelia Opie'3 Later Ye.mis.—She sud- denly discovered that all is vanity : she took to gray silks and muslin, and the " thee" and " thou," quoted Habakkuk and Micah with gusto, and set her heart upon preach- ing. That, however, was not allowed. Her Quaker friends could never be sufficiently sure how much was " imagination," and how much the instigation of "the inward witness;" and the privileged gallery in the chapel was closed against her, and her utterance was confined to loud sighs in the body of the Meeting. She tende I is decline ; she im- proved greatly in balance of mind and even- ness of spirits during her long and close in- timacy v ith the Gukneys : and there never l1 her beneficent disposi- tion, shown bv her family d -, no by her 1 i nnty to ti e poor. Her maj 5stic form moved through the narrow nt city, and her bright bag up the most wretched ever lost i ts bright nor the heart its youthfi dgayety. She was a merry laugher inner* even, if the truth be spoken, still a bit of a, romp—ready for bo-peep and hide-a'od-seek, in the midst of a morning call, or at the end of a grave conversation. She e-bjov d sho -ingpiim young Quaker girls her orna- ments, plumes and satins, and telling th-m when she wore them; and, when in I . -

Businessmen in the British Parliament, 1832-1886

Businessmen in the British Parliament, 1832-1886 A Study of Aspiration and Achievement Michael Davey A thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of History and Politics University of Adelaide February, 2012 Contents Abstract i Declaration ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 1. Getting There 17 2. Surviving 40 3. Doing 60 4. Legacies 94 Conclusion 109 Bibliography 116 Abstract The businessmen who were elected to the British Parliament after the First Reform Act had not acquired country estates or rotten boroughs as had their predecessors. They were critical of the established aristocratic dominance and they had policies they wanted to promote. Few succeeded in exerting any real influence due to the entrenched power of the landed gentry, their older age when elected and their lack of public experience. This thesis identifies six businessmen who were important contributors to national politics and were thus exceptions to the more usual parliamentary subordination to the gentry. They were generally younger when elected, they had experience in municipal government and with national agitation groups; they were intelligent and hard working. Unlike some other businessmen who unashamedly promoted sectional interests, these men saw their business activities as only incidental to their parliamentary careers. Having been in business did however provide them with some understanding of the aims of the urban working class, and it also gave them the financial backing to enter politics. The social backgrounds and political imperatives of this group of influential businessmen and how these affected their actions are discussed in this thesis. Their successes and failures are analysed and it is argued that their positions on policy issues can be attributed to their strong beliefs rather than their business background. -

William Edward

WILLIAM EDWARD THE MAN AND HIS POLICY. A P A P E R READ BEFORE THE HACKNEY YOUNG MEN’S LIBERAL ASSOCIATION, FRIDA Y, l UNE 2nd, 1882, BY ONE OF ITS MEMBERS; PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY t h e n a t i o n a l p r e s s a g e n c y , l i m i t e d, 13, Whitefriars Street, Fleet Street, B.C. 1882. PRICE TWOPENCE *** Some of the facts and a few of the expressions in this paper were used in an article on the same subject, which appeared in the Yorlcshireman of January 20th, 1877. I WILLIAM EDWARD FORSTER: THE MAN AND HIS POLICY A Paper read before the Hackney Young Men's Liberal Association, Friday, June 2nd, 1882. “ Where, liow, and why has this man failed ? ” Such is the question, or rather series of questions, arising in the minds of all interested in politics whenever some statesman, eminent in the councils of his party, trusted awhile in the Cabinet, and reckoned of much service in his country’s administration, falls or descends from the high position he has won, and from the back benches utters his jeremiads and prophesies inevitable woe. Secessions are not rare in politics, and each party has its own to mourn ; within •a very few years both Liberal and Conservative Cabinets have had to suffer the pangs of parting from colleagues of like mind with themselves up to a certain point, but of like mind no longer. The late Earl of Derby was bereft of the services of Lord Cranborne (now Marquis of Salisbury), of Lord Carnarvon, and of General Peel, because of differences upon Parliamentary Reform ; the late Earl of Beaconsfield lost two of his colleagues at the acutest crisis of the Eastern Question ; and Mr. -

“Noble Victory” in Gowel; That You Did Not Want the Credit for That Victory, but Shared It with Father O’Donoghue of Carrick-On-Shannon

Letter to Fr. O’Dowd, Gowel, Co. Leitrim from Jimmy Gralton following his deportation in 1933 __________________________________________________________________________________ New York City, U.S.A. n.d. (late 1933) Dear Father, Some time ago you stated in a sermon that you had gained a “noble victory” in Gowel; that you did not want the credit for that victory, but shared it with Father O’Donoghue of Carrick-on-Shannon. Now let us analyse this supposed victory of yours, and see what is noble about it. Let us see if there is anything connected with it that a decent minded man might be proud of. You started out a crusade against Communism by demanding that the Pearse- Connolly Hall be handed over to you. You knew the cash that paid for the material was given to the people of Gowel by P. Rowley, J.P. Farrell and myself. You also know that the labour was furnished free, and that it belonged to all the people of the area, irrespective of religious or political affiliations. But despite this you, with the greedy gall of a treacherous grabber, tried to get it into your own clutches. I put it to you straight, Father: is there anything noble about this? The people answered ‘No’ when they voted unanimously that you could not have it. The hall was in my name; you knew from experience that you could not frighten me into transferring it to you, so you organised a gang to murder me. You bullied little children, manhandled old women, lied scandalously about Russia, blathered ignorantly about Mexico and Spain, and incited young lads into becoming criminals by firing into the hall.