Am I a Fluxus Artist?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

Dissertatie Cvanwinkel

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism van Winkel, C.H. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Winkel, C. H. (2012). During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism. Valiz uitgeverij. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 7 Introduction: During the Exhibition the Gallery Will Be Closed • 1. RESEARCH PARAMETERS This thesis aims to be an original contribution to the critical evaluation of conceptual art (1965-75). It addresses the following questions: What -

David Quigley Learning to Live: Preliminary Notes for a Program Of

David Quigley In an essay published in 2009, Boris could play in a broader social context influenced the founding director John Groys makes the claim that “today art beyond the narrow realm of the art Andrew Rice, as well as the professors Learning to Live: education has no definite goal, no world. Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, Robert Preliminary Notes method, no particular content that can Motherwell, John Cage, and the poets be taught, no tradition that can be Performing Pragmatism: Robert Creeley and Charles Olson. for a Program of Art transmitted to a new generation—which Art as Experience Unlike other trajectories of the critique Education for the is to say, it has too many.”69 While one On the first pages of Dewey’s Art as of the art object, the Deweyian tradition might agree with this diagnosis, one Experience from 1934, we read: did not deny the special status of art in 21st Century. immediately wonders how we should itself but rather resituated it within a Après John Dewey assess it. Are we to merely tacitly “By one of the ironic perversities that continuum of human experience. Dewey, acknowledge this situation or does this often attend the course of affairs, the as a thinker of egalitarianism and critique imply a call for change? Is this existence of the works of art upon which democracy, created a theory of art lack (or paradoxical overabundance) of the formation of an aesthetic theory based on the fundamental continuity goals, methods or content inherent to depends has become an obstruction of experience and practice, making the very essence of art education, or is to theory about them. -

Major Exhibition Poses Tough Questions and Reasserts Fluxus Attitude

Contact: Alyson Cluck 212/998-6782 or [email protected] Major Exhibition Poses Tough Questions And Reasserts Fluxus Attitude Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life and Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond open at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery on September 9, 2011 New York City (July 21, 2011)—On view from September 9 through December 3, 2011, at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life features over 100 works dating primarily from the 1960s and ’70s by artists such as George Brecht, Robert Filliou, Ken Friedman, George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Mieko Shiomi, Ben Vautier, and La Monte Young. Curated by art historian Jacquelynn Baas and organized by Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art, the exhibition draws heavily on the Hood’s George Maciunas Memorial Collection, and includes art objects, documents, videos, event scores, and Fluxkits. Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life is accompanied by a second installation, Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond, in the Grey’s Lower Level Gallery. Fluxus—which began in the 1960s as an international network of artists, composers, and designers―resists categorization as an art movement, collective, or group. It also defies traditional geographical, chronological, and medium-based approaches. Instead, Fluxus participants employ a “do-it-yourself” attitude, relating their activities to everyday life and to viewers’ experiences, often blurring the boundaries between art and life. Offering a fresh look at Fluxus, the show and its installation are George Maciunas, Burglary Fluxkit, 1971. Hood designed to spark multiple interpretations, exploring Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, George Maciunas Memorial Collection: Gift of the Friedman Family; the works’ relationships to key themes of human GM.986.80.164. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

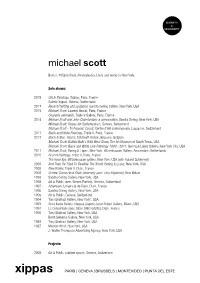

Michael Scott

BIOGRAPHY & BIBLIOGRAPHY michael scott Born in 1958 in Paoli, Pennsylvania. Lives and works in New York. Solo shows: 2018 Circle Paintings, Xippas, Paris, France Galerie Xippas, Geneva, Switzerland 2017 Recent Painting and sculpture, Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Michael Scott, Laurent Strouk, Paris, France Courants alternatifs, Triple V Gallery, Paris, France 2014 Michael Scott and John Chamberlain: a conversation, Sandra Gering, New York, USA Michael Scott, Xippas Art Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland Michael Scott - To Present, Circuit, Centre d’Art contemporain, Lausanne, Switzerland 2013 Black and White Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France 2012 Black & Blue, Galerie Odermatt-Vedovi, Brussels, Belgium Michael Scott: Buffalo Bulb’s Wild West Show, The Art Museum of South Texas, USA Michael Scott: Black and White Line Paintings 1989 - 2011, Gering & López Gallery, New York City, USA 2011 Michael Scott, Gering & López, New York, Witzenhausen Gallery, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2010 Recent Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France The Inner Eye, Witzenhausen gallery, New York, USA (with Roland Schimmel) 2009 And Then He Tried To Swallow The World, Gering & Lopez, New York, USA 2008 New Works, Triple V, Dijon, France 2002 Central Connecticut State University (avec Toby Kilpatrick), New Britain 1999 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1998 Art & Public (avec Steven Parrino), Geneva, Switzerland 1997 Atheneum, Université de Dijon, Dijon, France 1996 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1995 Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland 1994 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York*, USA 1993 Akira Ikeda Gallery, Nagoya (Japon) Jason Rubell Gallery, Miami, USA 1991 Le Consortium (avec Steve DiBenedetto), Dijon, France 1990 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA Brent Sikkema Gallery, New York, USA 1989 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA 1987 Mission West, New York, USA J. -

The Dialogical Imagination: the Conversational Aesthetic of Conceptual Art

THE DIALOGICAL IMAGINATION: THE CONVERSATIONAL AESTHETIC OF CONCEPTUAL ART MICHAEL CORRIS Within the history of avant-garde art there is a recurrent interest in process-based practices. A substantial claim made by proponents of this position argues that process-based practices offer far more scope for the revision of the conventional culture of art than any other type of practice. In the first place, process-based practices dispense with the idea of the production of a material object as the principle aim of art. While there is often a material ‘residue’ associated with process- based art, its status as an autonomous object of art is always questionable. Such objects are more properly understood as props or by-products, and are valued accordingly by the artist (but not, alas, by the critic, curator or collector). Process-based practices themselves raise difficult questions for connoisseurs; there is often no clear notion where to locate the boundary dividing process works from the environment at large. The process-based work of art may not result in an object at all; rather, it could be a performance (scripted or not), an environment or installation, an intervention in a public space, or some sort of social encounter, such as a conversation or an on-going project with a community. The point of all these practices is to radically alter the subject-position of both artist and beholder. By so doing, the very idea of the autonomy of art is placed in question. Once attention and purpose are shifted from the making of what amounts to medium- sized dry goods, so the argument goes, both artist and spectator are liberated. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

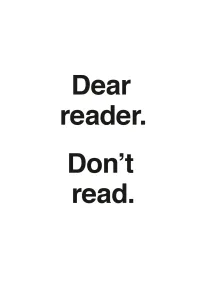

Dear Reader. Don't Read

1 Guy Schraenen Ulises Carrión Dear reader. Don’t read. The revolution engendered by access to knowledge on the Internet brings to the fore certain artistic projects of the past that seem to resonate with the present, as a kind of wake-up call or an invitation to reflect. This is the case, for instance, of the heterodox, multiform oeuvre of the artist, writer, and publisher Ulises Carrión. Right from its title, the exhibition Dear reader. Don’t read raises a paradox in the form of a negative imperative: it reminds us of the need to approach written text, literature, and hence culture as an ambiguous and contra- dictory field full of latent meanings that may perhaps even surface through their negation. The exhibition, which takes the thought-provoking form of a large exhibited—or “published”—archive, inquires into what a museum can contain, beyond traditional formats. It also explores what an art institution can do in the sense of giving voice to groups of thoughts that have been hidden by the veil of time and by the material complexity of the media in which they are expressed. The Ulises Carrión exhibition and publication are presented at a time when both the Museo Reina Sofía and its foundation are paying close attention to archives, particularly those related to Latin America’s cultural scene. Due to their very nature, these groups of units of knowledge are at risk of disappearing, either literally in the physical sense or by succumbing to oblivion and neglect, to the point where they can no longer be read or interpreted. -

Fluxus: the Is Gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Megan, "Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists" (2018). Honors College Theses. 178. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Fluxus movement of the 1960s and early 1970s laid the groundwork for future female artists and performance art as a medium. However, throughout my research, I have found that while there is evidence that female artists played an important role in this art movement, they were often not written about or credited for their contributions. Literature on the subject is also quite limited. Many books and journals only mention the more prominent female artists of Fluxus, leaving the lesser-known female artists difficult to research. The lack of scholarly discussion has led to the inaccurate documentation of the development of Fluxus art and how it influenced later movements. Additionally, the absence of research suggests that female artists’ work was less important and, consequently, keeps their efforts and achievements unknown. It can be demonstrated that works of art created by little-known female artists later influenced more prominent artists, but the original works have gone unacknowledged. -

Language Between Performance and Photography

Language Between Performance and Photography LIZ KOTZ Efforts to theorize the emergence of what can properly be called Conceptual art have struggled to determine the movement’s relationship to the linguistic, poetic, and performative practices associated with the prior moment of Happenings and Fluxus. More is at stake here than historicist questions of influence or precedents. The tendency to take at face value various claims— about the Conceptualist suppression of the object in favor of analytic statements or “information”—obscures what may be some of the most important accom- plishments of this work. To understand how the use of language in Conceptual art emerges from, and also breaks with, a more object-based notion of process and an overtly perfor- mance-based model of spectatorial interaction, we must understand it in a crucial historical context: the larger shift from the perception-oriented and “participa- tory” post-Cagean paradigms of the early 1960s to the overtly representational, systematized, and self-reflexive structures of Conceptual art. Although there is a tendency to see language as something like the “signature style” of overtly Conceptual work, it is important to remember that the turn to language as an artistic material occurs earlier, with the profusion of text-based scores, instruc- tions, and performance notations that surround the context of Happenings and Fluxus. Only in so doing can we understand what is distinct about the emergence of a more explicit and self-consciously “Conceptual” use of language, one which will employ it as both iterative structure and representational medium. This turn to language, I will argue, occurs alongside a pervasive logic structuring 1960s artis- tic production, in which a “general” template or idea generates multiple “specific” realizations, which can take the form of performed acts, sculptural objects, photo- graphic documents, or linguistic statements. -

Dada to Neo-Dada by Helen Molesworth

From Dada to Neo-Dada and Back Again Author(s): Helen Molesworth Source: October , Summer, 2003, Vol. 105, Dada (Summer, 2003), pp. 177-181 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/3397693 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October This content downloaded from 74.103.137.141 on Mon, 27 Jul 2020 23:43:32 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms From Dada to Neo-Dada and Back Again HELEN MOLESWORTH Several years ago, I went to a John Heartfield exhibition with a non-art historian friend. He walked around for about fifteen minutes and then said "I get this, it's like punk." This understanding of Dada as similar to a contemporary phenomenon made implicit sense to me; for Dada, as an art historical movement or entity, is often clearest in my mind in the guise of Neo-Dada. Even by the time of William Rubin's famous 1968 exhibition on Dada and Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art, the movement was being framed in terms of its "heritage." In Rubin's catalog, images of Dada works and those of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg appear side by side as if Dada existed first and foremost in a state of temporal and geographical collapse.