The Impact of Clustering of DFI on Urban Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMD 790GX 6 August 2008

AMD Launches World's Fastest Motherboard GPU: AMD 790GX 6 August 2008 it the best platform for unlocking maximum AMD Phenom processor performance. Built-in ATI Radeon HD 3300 graphics provide an unmatched HD and gaming experience out of the box, with flexibility to scale to high performance configurations with the addition of one or two award- winning ATI Radeon HD 4800 series discrete graphics cards. “Today’s high definition, multimedia applications demand powerful graphics and multi-core processor performance and only AMD is delivering a truly balanced platform that accelerates these AMD 790GX Chipset - Energy Efficient workloads,” said Phil Eisler, corporate vice president and general manager, AMD Chipset Division. “The AMD 790GX chipset contains several AMD innovations that further improves both AMD today announced the availability of the multi-core AMD Phenom processor performance industry’s preeminent performance desktop and motherboard ATI Radeon graphics platform, the AMD 790GX. Packing a host of performance, the result of which are versatile innovations, the AMD 790GX integrates advanced performance PCs that deliver an eye-catching performance tuning for AMD Phenom processors, visual experience.” plus ATI Radeon HD 3300 graphics - the world’s fastest motherboard graphics processor (mGPU) – Building on the momentum of the award-winning to take media aficionados beyond HD. AMD 780G chipset, the AMD 790GX offers DirectX 10 game compatibility, allowing casual gamers to In addition to AMD validation, independent testing enjoy advanced game performance, truly lifelike 3D of the AMD 790GX chipset shows significant graphics and dynamic interactivity in the latest increases in AMD Phenom processor performance game titles. -

G4V100-P Mini-Itx

G4V100-P Intel® 845GV Socket 478 Mini Board PROCESSOR LVDS TRANSMITTER • Intel® Pentium® 4 Processor with Hyper-Threading • Chrontel CH7017 Technology • Supports scale up to 1600x1200 pixels - 533MHz system data bus • 18-bit and 24-bit outputs • Intel® Pentium® 4 Northwood processor • 2D dither engine - 533MHz/400MHz system data bus • Support for second CRT DAC bypass mode • Intel® Celeron® Northwood processor • Dual LVDS supporting pixel rates up to 330Mpixels/sec - 400MHz system data bus when both 12-bit input ports are ganged together • Socket 478 ONBOARD AUDIO FEATURES CHIPSET • Realtek ALC202A • Intel® 845GV chipset • 18-bit stereo full-duplex codec with independent - Intel® 845GV Graphics Memory Controller Hub (GMCH) variable sampling rate - Intel® 82801DB I/O Controller Hub (ICH4) • S/PDIF-out interface SYSTEM MEMORY • 2-channel audio output • Two 184-pin DDR SDRAM DIMM sockets ONBOARD LAN FEATURES • 2.5V unbuffered PC1600 (DDR200), PC2100 (DDR266) or • Uses Intel 82562EM fast ethernet controller PC2700 (DDR333) DDR SDRAM DIMM • IEEE 802.3, 10BASE-T/100BASE-TX compliant physical • Supports maximum of 2GB system memory using 64Mbit, layer interface 128Mbit, 256Mbit or 512Mbit technology • IEEE 802.3u Auto-Negotiation - Double-sided x16 DDR SDRAM DIMM is not supported • Digital Adaptive Equalization control • Link status interrupt capability BIOS • 10BASE-T auto-polarity correction • Award BIOS, Windows® 98SE/2000/ME/XP Plug and Play • Alert on LAN functionality compatible • LAN Connect I/F • Supports SCSI sequential boot-up • 1:1 -

Tier-1 Motherboard Makers in Taiwan

Tier-1 Motherboard Makers in Taiwan Key Finding: As the desktop manufacturing industry in Taiwan is complicated and dynamic, each of the Taiwanese manufacturers, whether they delivered desktop, barebone or motherboard only, must demonstrate their competitive advantage and capability of maintaining existing partnerships and seeking new ODM/OEM opportunities. There are two kinds of the motherboard makers; system manufacturers and professional motherboard manufacturers. A few differences between system makers and professional motherboard makers are as follows: • System manufacturers ship the product mostly in full system whereas professional motherboard makers ship the product mostly in pure motherboard to their customers. • With few exceptions, most system manufacturers are more OEM-oriented whereas professional motherboard makers are more own-brand oriented. Therefore, the system manufacturers target at the MNVs (Multi-National Vendors) outsourcing businesses whereas the professional motherboard makers target the clone market with channel businesses. • System manufacturers have stronger global logistic supports than professional motherboard makers in order to fulfill the requirements from the MNV customers. System Manufacturers By definition, there are four Taiwan’s vendors that make the motherboard and the final assembly themselves, namely Acer, FIC, MiTAC and Tatung. They ship the products to TechInsight Inc. : 10F, 31, Jen-Ai Road, Sec 4, Taipei 106, Taiwan • Phone 886.2.2731.7288 • Fax 886.2.2731.8090 the customers in different formats including pure motherboard, barebone and full system. All the system manufacturers are both with OEM and own-brand businesses. However, they are more OEM-oriented since the OEM business accounted for 50% of their total revenues. These four PC makers are all tier-1 PC makers in Taiwan and produce various PC products including desktop PC, motherboard, notebook PC, PC server or personal workstation. -

CR901-B COM Express Basic Module User’S Manual

CR901-B COM Express Basic Module User’s Manual A20960511 1 Chapter 1 Introduction www.dfi .com Copyright FCC and DOC Statement on Class B This publication contains information that is protected by copyright. No part of it may be re- This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital produced in any form or by any means or used to make any transformation/adaptation without device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC rules. These limits are designed to provide reason- the prior written permission from the copyright holders. able protection against harmful interference when the equipment is operated in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not This publication is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer makes no installed and used in accordance with the instruction manual, may cause harmful interference representations or warranties with respect to the contents or use of this manual and specifi- to radio communications. However, there is no guarantee that interference will not occur in a cally disclaims any express or implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for any particular particular installation. If this equipment does cause harmful interference to radio or television purpose. The user will assume the entire risk of the use or the results of the use of this docu- reception, which can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encour- ment. Further, the manufacturer reserves the right to revise this publication and make changes aged to try to correct the interference by one or more of the following measures: to its contents at any time, without obligation to notify any person or entity of such revisions or changes. -

Motherboard C236M WS • Asrock

• ASRock - Motherboard C236 WS • ASRock - Motherboard C236 WSI • ASRock - Motherboard C236M WS • ASRock - Motherboard D1540D4U-2L+ • ASRock - Motherboard E3C232D2I • ASRock - Motherboard E3C232D4U • ASRock - Motherboard E3C232D4U-V1L • ASRock - Motherboard E3C232D4U-VF • ASRock - Motherboard E3C236D2I • ASRock - Motherboard E3C236D4HM-2L+ • ASRock - Motherboard E3C236D4HM-2T • ASRock - Motherboard E3C236D4M-4L • ASRock - Motherboard E3C236D4U • ASRock - Motherboard E3V5 WS • ASRock - Motherboard H110 Pro BTC+ • ASRock - Server Board D1521D4I • ASRock - Server Board D1521D4U-2L+ • ASRock - Server Board D1541D4U Series • ASUS/ASmobile - E3 PRO GAMING V5 • ASUS/ASmobile - ESC Server ESC500-G4 (P10S WS) • ASUS/ASmobile - P10S WS Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - P10S-C/4L Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - P10S-E/4L Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - P10S-I Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - P10S-M WS Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - P10S-V/4L Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - PRIME A320M-C R2.0 Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - PRIME A320M-E Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - PRIME A320M-K Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - RS Server RS100-E9-PI2 • ASUS/ASmobile - RS Server RS300-E9-PS4 (P10S-C/4L) • ASUS/ASmobile - RS Server RS300-E9-RS4 • ASUS/ASmobile - RS200-E9-PS2 Server • ASUS/ASmobile - RS200-E9-PS2-F Server • ASUS/ASmobile - Server Workstation WS660T • ASUS/ASmobile - TS Server TS100-E9-PI4 (P10S-X) • ASUS/ASmobile - TS Server TS300-E9-PS4 (P10S-E/4L) • DFI - SD631-C236 Motherboard • Gigabyte - GA-A320-DS3 Motherboard • Gigabyte - GA-A320M-D2P Motherboard • Gigabyte - GA-A320M-DS2 -

GV-3D1-7950-RH Geforce™ 7950 GX2

GV-3D1-7950-RH GeForce™ 7950 GX2 Rev. 102 * WEEE logo * WEEE © 2006 GIGABYTE TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD GIGA-BYTE TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD. ("GBT") GBT Macrovision corporation product notice: This product incorporates copyright protection technology that is protected by U.S. patents and other intellectual property rights. Use of this copyright protection technology must be authorized by Macrovision, and is intended for home and other limited viewing uses only unless otherwise authorized by Macrovision. Reverse engineering or disassembly is prohibited. 1. ....................................................................................................3 1.1. ................................................................................................. 3 1.2. ................................................................................................. 3 2. ............................................................................................4 2.1. ......................................................................... 4 2.2. ................................................................................................. 6 3. ................................................................................. 10 3.1. Win® XP .................................................................. 10 3.1.1. .............................................................................. 10 3.1.2. DirectX ................................................................................................. 10 3.1.3. ........................................................................................... -

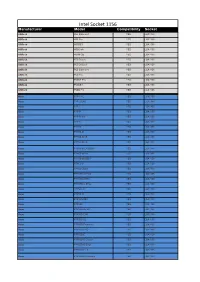

Intel Socket 1156 Manufacturer Model Compatibility Socket

Intel Socket 1156 Manufacturer Model Compatibility Socket ASRock H55 Extreme3 YES LGA1156 ASRock H55 Pro YES LGA1156 ASRock H55DE3 YES LGA1156 ASRock H55iCafe YES LGA1156 ASRock H55M-GE YES LGA1156 ASRock P55 Deluxe YES LGA1156 ASRock P55 Deluxe3 YES LGA1156 ASRock P55 Extreme4 YES LGA1156 ASRock P55 Pro YES LGA1156 ASRock P55DE Pro YES LGA1156 ASRock P55DE3 YES LGA1156 ASRock P55M Pro YES LGA1156 Asus P7F-C/4L YES LGA1156 Asus P7F-C/SAS YES LGA1156 Asus P7F-E YES LGA1156 Asus P7F-M YES LGA1156 Asus P7F-M WS YES LGA1156 Asus P7F-X YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55 YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55-M YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55-M LE YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55-M LX YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55-M LX/USB3 YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55-M Pro YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55-M/USB3 YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55-V YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55/USB3 YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55D-M EVO YES LGA1156 Asus P7H55D-M Pro YES LGA1156 Asus P7H57D-V EVO YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55 LX YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55-M YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55/USB3 YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D Deluxe YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D EVO YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D LE YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D Premium YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D PRO YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D-E YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D-E Deluxe YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D-E EVO YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D-E LX YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D-E Premium YES LGA1156 Asus P7P55D-E Pro YES LGA1156 Asus P7Q57-M DO YES LGA1156 Asus SABERTOOTH 55i YES LGA1156 Biostar H55A+ YES LGA1156 Biostar T5XE CFX-SLI YES LGA1156 Biostar TH55 HD YES LGA1156 Biostar TH55 XE YES LGA1156 Biostar TH55B HD YES LGA1156 Biostar TP55 YES LGA1156 Biostar TPower -

MB331-CRM System Board User’S Manual

MB331-CRM System Board User’s Manual A20800209 Copyright This publication contains information that is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced in any form or by any means or used to make any transfor- mation/adaptation without the prior written permission from the copyright hold- ers. This publication is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer makes no representations or warranties with respect to the contents or use of this manual and specifically disclaims any express or implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose. The user will assume the entire risk of the use or the results of the use of this document. Further, the manufacturer reserves the right to revise this publication and make changes to its contents at any time, without obligation to notify any person or entity of such revisions or changes. © 2012. All Rights Reserved. Trademarks All trademarks and registered trademarks of products appearing in this manual are the properties of their respective holders. FCC and DOC Statement on Class B This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference when the equipment is operated in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instruction manual, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. However, there is no guarantee that interference will not occur in a particular installation. -

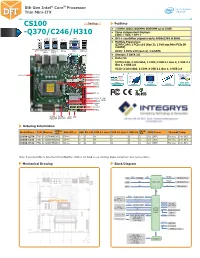

Cs100 -Q370/C246/H310

8th Gen Intel® CoreTM Processor Thin Mini-ITX CS100 Desktop Features • 2 DDR4 1866/2666MHz SODIMM up to 32GB • Three independent displays: -Q370/C246/H310 LVDS + VGA + DP++ LAN 2 LAN 1 COM • DP++ resolution supports up to 4096x2304 @ 60Hz Mic-in DP++ • Multiple Expansions: Q370/C246: 1 PCIe x16 (Gen 3), 1 Full-size Mini PCIe (& mSATA) Line-out USB 3.1 USB 3.0 DP++ VGA USB 2.0 H310: 1 PCIe x16 (Gen 3), 1 mSATA Gen 1 Gen 2 • Storage: 3 SATA 3.0 • Rich I/O: Q370/C246: 2 Intel GbE, 2 COM, 2 USB 3.1 Gen 2, 2 USB 3.1 USB 2.0 Gen 1, 4 USB 2.0 H310: 2 Intel GbE, 2 COM, 4 USB 3.1 Gen 1, 4 USB 2.0 PCIe x16 CPU Fan 4096x2304 air gap ±15kv Mini PCIe 25mm LVDS Intel Core Thin 4K2K COM ESD i7/i5/i3 Mini-ITX DP++ Display DDR4 Protection LPC SATA 3.0 Intel Q370/C246/ H310 BAT System Fan ATX power SMBus DDR4_2 DDR4_1 DIO DIO SODIMM SODIMM Power Ordering Information LVDS/ SATA Model Name P/N Memory eDP VGA/DP++ GbE RS-232 USB 3.1 Gen 2 USB 3.1 Gen 1 USB 2.0 3.0 TPM Power Thermal Temp. CS100-Q370 TBD 2 SODIMM LVDS DP++ 2 2 4 2 8 3 2.0 ATX Fanless 0 to 60oC CS100-C246 TBD 2 SODIMM LVDS DP++ 2 2 4 2 8 3 2.0 ATX Fanless 0 to 60oC CS100-H310 TBD 2 SODIMM LVDS DP++ 2 2 0 4 4 3 2.0 ATX Fanless 0 to 60oC Note: If you would like to have the CPU confi guration which is not listed on our ordering, please contact our sales representative. -

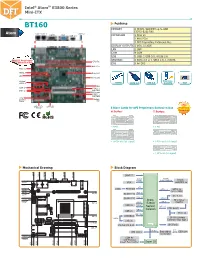

Intel® Atomtm E3800 Series Mini-ITX Atom

Intel® AtomTM E3800 Series Mini-ITX BT160 Features MEMORY 2 DDR3L SODIMM up to 8GB (-E45/-E26/-J00) Atom LAN 2 LAN 1 USB 3.0 COM 1 VGA USB 2.0 EXPANSION 1 PCIe x1 1 Mini PCIe 1 DFI Proprietary Extension Bus DISPLAY OUTPUTS 1 VGA, 1 LVDS LAN 2 LAN COM 4 COM USB 5 USB: 1 USB 3.0, 4 USB 2.0 STORAGE 2 SATA 2.0 or 1 SATA 2.0, 1 mSATA One DFI Proprietary CPU Fan Extension Bus DIO 8-bit DIO Mini PCIe PCIe x1 USB 2.0 Atom SoC LPC ATX Power Vertical USB Drive USB 2.0 DDR3L SATA 2.0 USB 3.0 Security VGA DIO COM 2-4 DDR3_2 SATA 2.0 SODIMM DIO Power DDR3_1 SODIMM LCD/ Inverter System Power Fan DFI's LVDS LCD LAN LED Panel 5 Riser Cards for DFI Proprietary Extension Bus Proprietary H Series: T Series: Technology • 3 PCI • 3 PCI • 1 PCIe x16 (x1 signal) • 1 PCIe x16 (x1 signal) • 1 PCIe x8 (x1 signal) Mechanical Drawing Block Diagram 0.00 17.82 34.82 59.82 94.83 121.82 IMVP-7 Analog DDR3L Display 1066/1333MHz DDR3L 10.16 VGA SODIMM 2x 0.00 eDP PTN3460 18.85 LVDS SATA 2.0 SATA 1x (SATA DOM) 20.48 22.86 PCIe x1 22.86 GLAN I210 SATA 1x PCIe x1 GLAN I210 SATA 2.0 42.04 Atom Mini PCIe/ USB 2.0 46.97 52.02 USB 3.0 E3800 mSATA USB 1x USB 2.0 Series/ PCIe x1 PCIe Swich USB 2.0 Celeron USB 2x USB HSIC PCIe x1 93.02 USB4604 USB 2.0 DFI Proprietary USB 2x Extension Bus (Opt.) 113.41 Digital I/O 8-bit SPI Flash 128.14 2 LPC Bus I C TPM (Opt.) Embedded EEPROM Controller 154.94 COM 4x 163.65 115.88 128.78 159.84 157.48 61.98 74.88 11.76 H/W Monitor 6.35 0.00 Smart Fan Control Super IO Intel® AtomTM E3800 Series Mini-ITX BT160 Specifications * Optional and is not supported in standard model. -

KVR16LN11-8.Pdf

ATERA INFORMÁTICA LTDA. internet:http://www.atera.com.br R. Oliveira Alves, 147 - Ipiranga - 04210-060 - São Paulo - SP - tel:(11) 2272-2255 - fax:(11) 2272 -5593 ATERA Placas mãe compatíveis com a memória: Kingston ( KVR16LN11/8 )) 8 GB Module - DDR3L 1600MHz • ASRock - Motherboard B150 Combo • ASRock - Motherboard B150M Combo-G • ASRock - Motherboard B150M Pro4/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard B150M Pro4S/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard B150M-HDV/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard B150M-ITX/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard D1800M • ASRock - Motherboard Fatal1ty B150 Gaming K4/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard Fatal1ty H170 Performance/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard Fatal1ty Z170 Gaming K4/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard H110M Combo-G • ASRock - Motherboard H110M-DVS/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard H110M-GL/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard H110M-HDV/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard H170 Combo • ASRock - Motherboard H170 Pro4/D3 • ASRock - Motherboard Q1900M • ASRock - Motherboard Z170 Pro4/D3 • ASRock - Server Board C2550D4I • ASRock - Server Board C2750D4I • ASUS/ASmobile - 170 Motherboard H170-PLUS D3 • ASUS/ASmobile - 170 Motherboard H170I-PLUS D3 • ASUS/ASmobile - 170 Motherboard H170M-E D3 • ASUS/ASmobile - 170 Motherboard Z170-P D3 • ASUS/ASmobile - 170 Motherboard Z170M-E D3 • ASUS/ASmobile - 970 Pro Gaming Aura • ASUS/ASmobile - B150 PRO GAMING 3 Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - B150 PRO GAMING D3 Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - B150-PLUS D3 Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - B150-PRO D3 Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - B150M-A D3 Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - B150M-C D3 Motherboard • ASUS/ASmobile - B150M-D -

Registered Electronics Manufactures

MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Land Management Administration • Resource Management Program 1800 Washington Boulevard • Suite 610 • Baltimore, Maryland 21230-1719 410-537-3314 • 800-633-6101 x3314 • www.mde.maryland.gov Registered Electronics Manufactures per Maryland's Statewide Electronics Recycling Program Law eManufacturers Registered to Sell Products in Maryland from March 1, 2017 to February 28, 2018 (Manufacturer links are provided for companies with Department-approved takeback programs and that will recycle their electronic device brands for free. Additional manufacturer links are provided in the "Electronics Take Back and Recycling Programs" section on the eCycling homepage.) • 3M Touch Systems, Inc. (010406-22; 3M Dynapro, 3M Microtouch, 3M Touch Systems, Dynapro) • Aberdeen LLC (021113-130) • Acer America Corporation (122005-04; Acer, Gateway) • Aluratek, Inc. (090414-182; Aluratek) • Amazon Fulfillment Services, Inc. (092413-154; Kindle Fire, Fire) • American Reliance, Inc. (011911-107; Amrel, Rocky) • American Network Solutions (080616-243; Sprint State, American Network Solutions, ANS) • Apple, Inc. (122805-16; Apple, Next) • Arcadian Computers LLC (121615; Arcadian, Gigabyte, ASUS, Samsung, Intel, Corsair) • ASUS Computer International (010610-97; ASUS, Nexus ASUS) • Atyme Corporation, Inc. (040317-248; Atyme) • Baby's Journey, Inc. (063015-216; Babies R US, AT&T) • Bang & Olufsen America, Inc. ( 050208-87; Bang & Olufsen) • Barco, Inc. (091113-153; Barco) • Best Buy (053105-36; Insignia, Dynex, Toshiba, Sharp, Digiland) • Blackberry Ltd. (12111-125; BlackBerry Z30, BlackBerry Leap, BlackBerry Passport, Blackberry PRIV smartphone, DTEK50 Smartphone, DTEK60 smartphone) • BLU Products, Inc. (092214-191; BLU) • Boxx Technologies, Inc.(042015-205; Boxx, Go Boxx, Render Boxx, Apexx) • BULL ITT Group LLC. (080317-250; CAT) • Canon U.S.A, Inc.