I Love Me Some Datives: Expressive Meaning, Free Datives, and F-Implicature Laurence R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

)Lot 100 Airplay.. 82 ALL by MYSELF (Eric Carmen

Billboard. JULY 26, 1997 HOT 100 A -Z Billboar+d. JULY 26, 1997 TITLE (Publisher - Licensing Org.) Sheet Music Dist. 53 5 MILES TO EMPTY (The Night Rainbow. ASCAP/Brown Girl. ASCAP/Mike's Rap. BMI) HL 55 6 UNDERGROUND (BMG. ASCAP/EMI Unart. BMI) HL/WBM 100 SalesT. )lot 100 Airplay.. 82 ALL BY MYSELF (Eric Carmen. BMI/Songs 01 Not Sin les Compiled from a national sample of airplay supplied by Broadcast Data Systems' Radio Track service. PolyGram Intl. BMI) HL Compiled from a national sample of POS (point of sale) quipped retail stores and rack outlets which report 333 stations are electronically monitored 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Songs ranked by gross impres- 22 ALL FOR YOU (Music Corp. 01 America. BMI/Cherry. mber of units sold to SoundScan, Inc. This data is u d in the Hot 100 Singles chart. SoundScan® sions, computed by cross -referencing exact times of airplay with Arbitron listener data. This data BMI/Crooked Chimney, Inc.. BMI) HL Is used in the Not 100 Singles chart. 35 ALONE (Careers -BMG. BMI/Gibb Brothers, BMI) HL 1111111 25 BARELY BREATHING (Duncan Sheik, BMVHapp Dog. w W W es ZO =O BMI /Careers -BMG, BMI) HL Ó 0 2 BITCH (Kissing Booth, BMI/Warner- Tamerlane, BMI/Hidden 3 3 ti W Et 6- TITLE o v;- TITLE Pun, BMI/Sushi Too, BM/EMI Blackwood. BMI) HLAVBM TITLE yy TITLE ARTIST (LABEL/PROMOTION LABEL) 4 ] ; ARTIST (LABEL/PROMO1IO' . ACE L) ] % ARTIST (LABEUPROMOTION LABEL) 37 BUTTERFLY KISSES (Polygram Int'I, ASCAP /Diadem, ARTIS' 9N LABEL) r 7 3 SESAC) HL/WBM I BELIEVE I CAN FLY 38 35 39 Into 1 38 41 14 * * NO. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 5-22-1997 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (1997). The George-Anne. 1480. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/1480 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The 'i Georgia Southern University's Official Student Newspaper Statesboro, Georgia 30460 Founded 1927 GOLD EDITION Officials: increased security helps Playerz Ball run smoothly Thursday May 22,1997 Statesboro Police Chief Richard Malone said only then arrests related to the event were reported over the weekend Vol. 70, No. 14 By Keyla McNeely event like Playerz Ball causes traffic were angered by the amount of law traffic and kept cars flowing through- The oldest continuously Staff Writer congestion and confusion, the local po- enforcement brought in, but none would published newspaper in out the complex. This was the happen- Bulloch County Anticipation of last weekend's lice are allowed to bring in surround- comment on the record. ing place!" Playerz Ball brought in the University ing law enforcement agents to help ad- Road blockings, apartment com- Southern Villa sent out letters to its Sports Police, Drug Task Force, GBI, Tri-Cir- minister the situation." plexes being monitored and the residents stating that no visitors and cuit Task Force and Georgia State Pa- Despite the many concerns of the amount of guests allowed in apartment no gatherings would be allowed on the trol to assist the local law enforcement Statesboro police, local residents and complexes being limited concerned the premises. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

A 3Rd Strike No Light a Few Good Men Have I Never a Girl Called Jane

A 3rd Strike No Light A Few Good Men Have I Never A Girl Called Jane He'S Alive A Little Night Music Send In The Clowns A Perfect Circle Imagine A Teens Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens Can't Help Falling In Love With You A Teens Floor Filler A Teens Halfway Around The World A1 Caught In The Middle A1 Ready Or Not A1 Summertime Of Our Lives A1 Take On Me A3 Woke Up This Morning Aaliyah Are You That Somebody Aaliyah At Your Best (You Are Love) Aaliyah Come Over Aaliyah Hot Like Fire Aaliyah If Your Girl Only Knew Aaliyah Journey To The Past Aaliyah Miss You Aaliyah More Than A Woman Aaliyah One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah Rock The Boat Aaliyah Try Again Aaliyah We Need A Resolution Aaliyah & Tank Come Over Abandoned Pools Remedy ABBA Angel Eyes ABBA As Good As New ABBA Chiquita ABBA Dancing Queen ABBA Day Before You Came ABBA Does Your Mother Know ABBA Fernando ABBA Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie ABBA Happy New Year ABBA Hasta Manana ABBA Head Over Heels ABBA Honey Honey ABBA I Do I Do I Do I Do I Do ABBA I Have A Dream ABBA Knowing Me, Knowing You ABBA Lay All Your Love On Me ABBA Mama Mia ABBA Money Money Money ABBA Name Of The Game ABBA One Of Us ABBA Ring Ring ABBA Rock Me ABBA So Long ABBA SOS ABBA Summer Night City ABBA Super Trouper ABBA Take A Chance On Me ABBA Thank You For The Music ABBA Voulezvous ABBA Waterloo ABBA Winner Takes All Abbott, Gregory Shake You Down Abbott, Russ Atmosphere ABC Be Near Me ABC Look Of Love ABC Poison Arrow ABC When Smokey Sings Abdul, Paula Blowing Kisses In The Wind Abdul, Paula Cold Hearted Abdul, Paula Knocked -

Bobby Brown's Karaoke Rentals 503-422-7177 by Artist

Bobby Brown's Karaoke Rentals 503-422-7177 by Artist +44 10cc When Your Heart Stops Beating Wall Street Shuffle 01 11 15 Minutes Until The Karaoke Welcome To Our Saturday Gig Starts (5 Min Track) 112 02 Come See Me 10 Minutes Until The Karaoke Cupid Starts (5 Min Track) Dance With Me 03 It's Over Now 5 Minutes Until The Karaoke Starts Only You (5 Min Track) Peaches & Cream 04 Right Here For You U Already Know Hola! Bonjour! Wilkommen! Welcome! 112 & Ludacris 05 Hot & Wet Welcome To The Karaoke Show 112 & Super Cat 06 Na Na Na Welcome To Our Monday Gig 12 07 Welcome To Our Sunday Gig Welcome To Our Tuesday Gig 12 Gauge 08 Dunkie Butt Welcome To Our Wednesday Gig 12 Stones 09 Crash Welcome To Our Thursday Gig Far Away We Are One 1 Giant Leap & Maxi, 13 Jazz & Robbie Take A Look Through The Song Williams Books My Culture 14 10 Take Your Requests To The Welcome To Our Friday Gig Karaoke Host 10 Years 15 Beautiful We Need Volunteers For The Karaoke Through The Iris Wasteland 16 The Region's Number 1 Karaoke 10,000 Maniacs Venue Because The Night Candy Everybody Wants 17 Like The Weather It's Kamikaze Karaoke More Than This 18 These Are The Days It's 'Out Of The Hat' Karaoke! Trouble Me 19 100 Days 100 Nights Win A Beer! Sing Kamikaze Jones, Sharon 1910 Fruitgum Co. 100 Proof Aged In 1, 2, 3 Redlight Soul Simon Says Somebody's Been Sleeping 1975 101 Dalmations Antichrist Cruella De Vil Chocolate 10cc City Love Me Donna Sex.... -

2 Column Indented

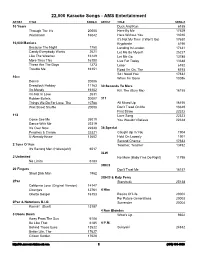

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Videos Karaoke 25

Listado General (Internacional) 2 / 183 By MillóndeKaraoke TEMAS VARIADOS INTERNACIONALES INGLES VARIED 3LW - No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 9244 tracks in Playlist files: 3T- Anything 4 Non Blondes - What's Up 10 Cc - Donna 4PM - Sukiyaki 10 Cc - I'm Mandy 5ive - Don't Wanna Let You Go 10 Cc - I'm Not In Love 5ive - Keep On Movin 10 Cc - Rubber Bullets 911 - A Little Bit More 10.000 Maniacs - Because The Night 911 - All I Want Is You 10.000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 1910 Fruitgum Company - Simon Says 911 - More Than A Woman 21 Demands - Give Me A Minute 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 21st Century Girls - 21st Century Girls 911 - Private Number 3 Doors Down - Away from the sun 98 Degrees - Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 3 Doors Down - Be like that 98 Degrees - Hardest Thing 3 Doors Down - Duck And Run 98 Degrees - I Do (Cherish You) 3 Doors Down - Here Without You 98 Degrees - I Do Cherish You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 98 Degrees - My Everything 3 Doors Down - Let Me Go 98 Degrees - True To Your Heart 3 Doors Down - Loser A Flock Of Seagulls - Wishing (If I Had A Photograp 3 Doors Down - The Road I'm On A T C - Around The World 3 Doors Down - When I'm Gone A Taste Of Honey - Boogie Oogie Oogie 35L - Take It Easy A Teens - Bouncing Off The Ceiling (Upside Down) 38 Special - Caught Up In You A1 - Caught In The Middle 38 Special - Hold On Loosely A1 - Everytime Listado General (Internacional) 3 / 183 By MillóndeKaraoke A1 - Like A Rose ABBA - Rock Me A1 - Make It Good ABBA - S O S A1 - No