Cake and Cockhorse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merry Wives (Edited 2019)

!1 The Marry Wives of Windsor ACT I SCENE I. Windsor. Before PAGE's house. BLOCK I Enter SHALLOW, SLENDER, and SIR HUGH EVANS SHALLOW Sir Hugh, persuade me not; I will make a Star-chamber matter of it: if he were twenty Sir John Falstaffs, he shall not abuse Robert Shallow, esquire. SIR HUGH EVANS If Sir John Falstaff have committed disparagements unto you, I am of the church, and will be glad to do my benevolence to make atonements and compremises between you. SHALLOW Ha! o' my life, if I were young again, the sword should end it. SIR HUGH EVANS It is petter that friends is the sword, and end it: and there is also another device in my prain, there is Anne Page, which is daughter to Master Thomas Page, which is pretty virginity. SLENDER Mistress Anne Page? She has brown hair, and speaks small like a woman. SIR HUGH EVANS It is that fery person for all the orld, and seven hundred pounds of moneys, is hers, when she is seventeen years old: it were a goot motion if we leave our pribbles and prabbles, and desire a marriage between Master Abraham and Mistress Anne Page. SLENDER Did her grandsire leave her seven hundred pound? SIR HUGH EVANS Ay, and her father is make her a petter penny. SHALLOW I know the young gentlewoman; she has good gifts. SIR HUGH EVANS Seven hundred pounds and possibilities is goot gifts. Enter PAGE SHALLOW Well, let us see honest Master Page. PAGE I am glad to see your worships well. -

2018 Accounts Word Format of Trustees Report and Statement.Docx

. .• - Registered number: 08569207 SOUTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE CHURCH OF ENGLAND MULTI ACADEMY TRUST (A company limited by guarantee) ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 AUGUST 2018 .. r. SOUTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE CHURCH OF ENGLAND MULTl ACADEMY TRUST (A company limited by guarantee) CONTENTS Page Reference and administrative details 1 Trustees' report 2-12 Governance statement 13 - 15 Statement on regularity, propriety and compliance 16 Statement of Trustees' responslbllltles 17 Independent auditor's report on the financial statements 18 - 20 Independent reporting accountant's assurance report on regularity 21 - 22 Statement of financial activities incorporating income and expenditure account 23 Balance sheet 24 Statement of cash flows 25 Notes to the financial statements 26-42 SOUTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE CHURCH OF ENGLAND MULTI ACADEMY TRUST (A company limited by guarantee) REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 AUGUST 2018 Members M P Hough Robinson Peterborough Diocese Church Schools Trust Trustees Peterborough Diocese Church Schools Trust R Hazelgrove (until June 2018) 0 Johnson, Accounting Officer (until Jan 2018) SJ Allen( appointed Chair Jan 2018) G N Nunn1 AJ Osborne J Moffitt B Gundle (until Jan 2018) P Deane 1 C Wade, Chairman (until December 2017) A E Allen (appointed Accounting Officer Jan 2018) P Beswick (appointed Jan 2018) G Bruce (appointed Jan 2018) 1 Member of the Finance Committee Company registered number 08569207 Company name South Northamptonshire Church of England Multi Academy Trust -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

![The Pursuit of Happiness :-) 2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5696/the-pursuit-of-happiness-2-675696.webp)

The Pursuit of Happiness :-) 2]

THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS :-) 2] Simon Beattie CTRL+P The Pursuit of Happiness Ben Kinmont CTRL+P Honey & Wax CTRL+P On January 20, 2021, the four of us were Justin Croft CTRL+P on a Zoom call, throwing around ideas for a joint list while Ben and Heather kept an eye on the presidential inauguration. In the best American spirit, Simon suggested 'the pursuit of happiness.' And here we are. May the offerings in this list bring you joy! 3] The Pursuit of Happiness Heather O’Donnell runs Honey & Wax Simon Beattie specialises in European Booksellers in Brooklyn, New York, dealing (cross-)cultural history, with a particular primarily in literary and print history, with interest in the theatre and music. His 10th- an emphasis on cultural cross-pollination. anniversary catalogue, Anglo-German She is a founder of the annual Honey & Cultural Relations, came out last year. As Wax Book Collecting Prize, now in its fifth the founder of the Facebook group We year, an award of $1000 for an outstanding Love Endpapers, Simon also has a keen collection built by a young woman in the interest in the history of decorated paper; United States. an exhibition of his own collection is planned for 2022. He currently sits on the Council Heather serves on the ABAA Board of of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association, Governors, the faculty of the Colorado and teaches regularly at the York Antiquarian Antiquarian Book Seminar (now CABS- Book Seminar. Minnesota), and and the Yale Library Associates Trustees. She has spoken about Simon also translates, and composes. -

Brasenose Cottage, 47 High Street, Middleton Cheney, Oxfordshire, OX17

Brasenose Cottage, 47 High Street, Middleton Cheney Brasenose Cottage, 47 High Street, Middleton Cheney, On the first floor there is a spacious landing that Oxfordshire, OX17 2NX leads to the generous principal bedroom with en suite shower room, three further well-appointed bedrooms, and a family bathroom window seat A Grade II Listed semi-detached four/ and storage. five bedroom property situated in the popular village of Middleton Cheney. Outside The property is approached via a five-bar gate Banbury 3 miles (London Marylebone in under and a generous block-paved driveway providing 1 hour), Brackley 6 miles, M40 (J11) 2.5 miles, private parking for multiple vehicles. The well- Bicester 16 miles, Oxford 29 miles. maintained secluded garden features a lawn and a terrace area which is surrounded by mature Porch/Boot room | Kitchen/breakfast room trees, a pond and some mature shrubs and Family room | Dining room | Sitting room | trees. There is also a summer house and double Utility room/cloakroom | Ground floor bedroom garage with an adjoining log store. 5/Gym/Office | Principal bedroom with en-suite shower room | Three further double bedrooms Location Bathroom | Double garage | Off-road parking Middleton Cheney lies approximately three Garden | EPC Rating TBC miles east of Banbury. and is positioned on the borders of North Oxfordshire and South The Property Northamptonshire, it is a popular and active Brasenose Cottage is a substantial Grade II village. Village amenities include a library, Listed four-bedroom property positioned in Co-op, pharmacy, post office, bus service, the heart of the popular village of Middleton newsagents, cafe, beauticians, hair dressers, fish Cheney. -

AS THIN AS BANBURY CHEESE Martin Thomas in "The Merry Wives of Windsor" (1597), 1 Shakespeare Has Bardolf Address Slender As "You Banbury Cheese"

AS THIN AS BANBURY CHEESE Martin Thomas In "The Merry Wives of Windsor" (1597), 1 Shakespeare has Bardolf address Slender as "You Banbury Cheese". This is not just some local reference by a Warwickshire man: at the time, Banbury was nationally famous for its cheese. Indeed, it was better known for its Banbury Cheese than for its Banbury Cakes. Banbury Cheese is variously described as having a keen, sharp savour,2 and soft, rich3 and creamy.4 It was golden yellow in colour5 with an outer skin that needed to be pared off.6 In the sixteenth century at least, there were hard and soft versions. It was round, and only about one inch thick' — hence the Shakespearean insult. Surprisingly, perhaps, given Banbury's long association with the wool trade, it was made with cow's milk, not sheep's milk.8 The centre of Banbury's cheese-making seems to have been the Northamptonshire hamlets, Grimsbury and Nethercote, although some cheese was made in the town and the Oxfordshire hamlets.9 The main cheese market was in the vicinity of the old High Cross,10 in the Market ' William Shakespeare. The Merry Wives of Windsor, Act 1 Scene 1. 2 Richard Jones, The Good Huswifes Handmaid for the Kitchin (1594). 3Daniel Defoe, Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, published between 1724 and 1727. 4 Camden's Britannia (1607). 5 As fn.2. 6 Jack Drum's Entertainment (1601) 7 Victoria County History A History of the County of Oxford: Vol 10: Banbury hundred (1972) [VCII] , 'Origins and growth of the town', pp. -

A Village Magazine for Byfield December/January 2021

The Byword A Village Magazine for Byfield December/January 2021 We wish all our readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year Magazine and Parish Information A magazine published by Holy Cross Church, Byfield, for all the residents in the village. The magazines are issued in February, April, June, August, October and December. Contributions are always welcome: copy to the Editor by the first Sunday of the preceding month, please. Editor: Miss Pam Hicks ([email protected]) Tel: 261257 Advertising: Mrs Lyn Grennan, 35 The Twistle Tel: 261596 Distribution: Mrs Lyn Grennan, 35 The Twistle Tel: 261596 Parish Church of Holy Cross: Rector Lay Reader Mrs Lesley Palmer Tel: 264374 Churchwardens: Mrs Chris Cross, 28 Bell Lane Tel: 260764 Mrs Lyn Grennan, 35 The Twistle Tel: 261596 Hon. Treasurer: Miss Pam Hicks, 1 Edwards Close Tel: 261257 Deputy Treasurer: Mrs Diana Charters Tel: 261725 Baptisms, Banns, Marriages, Funerals: Contact a churchwarden as above Choir Practice: Wednesdays at 7.00pm. Organist: Choir Mistress: Mrs Alison Buck ([email protected]) Tel: 260977 Bell ringing Practice: Fridays at 7.30pm but suspended at present due to Covid-19 Tower Captain: Mr James Grennan Tel: 261596 Methodist Church: Minister: Revd. Lin Francis ([email protected]) Tel: 01295 262602 R.C. Church of the Sacred Heart, Main Street, Aston le Walls: Parish Priest: Father John Conroy, The Presbytery, Aston le Walls Tel: 01295 660592 Stagecoach (Banbury) 01865 772250 Useful Telephone Numbers TRANSCO Gas 0800 111 999 Anglian Water 0800 771 881 Byfield Medical -

Guestbook Archive

RAF STATION UPPE R HEYFORD Memorial Web Site GUEST BOOK ARCHIVE 2002 www.raf-upper-heyford.org Tuesday 12/31/2002 7:30:34pm Name: Mark A Tait E-Mail: [email protected] City/Country: linwood nj Comments: I was at raf upper heyfor from fall 1980-1982. I was in the 20TH AMS and then the 20TH CRS. I am still in the AF with the 177th FW Jersey Devils. Tuesday 12/31/2002 6:31:50pm Name: marilyn yaxley-russell E-Mail: [email protected] City/Country: Florida, USA Comments: I was brought up in Headington, Oxford..and Upper Heyford was always a part of my family's life..I feel really sad thinking that it is no more...I married a GI, Larry Russell (stationed in OMS 1975-1979)..and we now live in Florida..but when we went back for a vacation in 2000 it was very nostalgic for us both..it bought a lump to my throat seeing the buildings so empty and unkempt and remembering all the wonderful times we had there..I LOVED that place..it was like a little piece of America...so new...so exciting..and so many happy times..and so many nice friendly people...!!!My friend, Diana and I had our first Tequilla Sunrise in the All ranks club..Met new people, English locals,Charmaine, Philomena both from Woodstock.. and Americans.The summers of 1975 and 1976 were great, we had some of the best hot sunny DRY days..Had some fun dancing the night away there,and in the brass Bar...We were stationed back there again in 1990-1994...we closed the base, one of the last families to leave there in June 1994...I worked at the Merchants Bank for a short time,...awful place..with some awful people managing it...oops guess I shouldnt say that!!!! How I wish Upper Heyford as a USAF base was still up and running...Ill always have the best memories of Upper Heyford.. -

Long Cottage, Marston St. Lawrence, Banbury, Northamptonshire Long Cottage, Outside Marston St

Long Cottage, Marston St. Lawrence, Banbury, Northamptonshire Long Cottage, Outside Marston St. Walled garden to rear with mature shrubs and trees which the landlord's gardener maintains. Lawrence, Banbury, The tenant is responsible for mowing and Northamptonshire edging of borders. Single open garage. Two outbuildings ideal for storage. Utility room with OX17 2DA shelved storage and space for a tumble dryer A delightful Grade II listed thatched Location cottage situated on the edge of the village. Part garden maintenance Marston St. Lawrence is a very popular and included. Available for a minimum attractive village five miles north east of term of 12 months. Pets by negotiation Banbury on the Oxfordshire/Northamptonshire border. Traditional village with mainly stone built period properties and a parish church surrounded by unspoilt countryside with plenty M40 (J11) 4 miles, Banbury 5 miles, Brackley of public footpaths and bridleways. 5 miles, Oxford 23 miles, London 82 miles, Banbury to London Marylebone 56 minutes Nearby Middleton Cheney has good local shops ENTRANCE HALL | SITTING ROOM | DINING and amenities. Comprehensive shopping ROOM | KITCHEN/BREAKFAST ROOM | facilities in the market towns of Banbury UTILITY ROOM/CLOAKROOM | 3 BEDROOMS | and Brackley. Local primary and secondary FAMILY BATHROOM | SEPARATE WC | SINGLE schools at Middleton Cheney and Brackley and OPEN GARAGE | 2 OUTBUILDINGS | WALLED independent schools at Brackley, Westbury and GARDEN Overthorpe, Stowe, Bloxham and Tudor Hall. Leisure facilities include racing at Towcester, Directions General EPC Rating E Cheltenham, Stratford and Warwick, polo at Kirtlington Park, Southam and Cirencester Park, From J11 of the M40 take the A422 east. At the Local Authority: South Northants DC motor racing at Silverstone and theatres in Middleton Cheney roundabout take the 2nd Services: Mains electricity, water and drainage. -

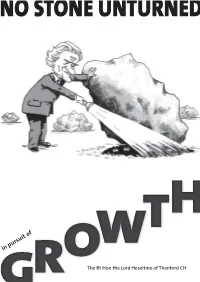

No Stone Unturned �

NO STONE UNTURNED � H T in pursuit of OW GR The Rt Hon the Lord Heseltine of Thenford CH Unless I can secure for the nation results similar to those which‘ have followed the adoption of my policy in Birmingham … it will have been a sorry exchange to give up the town council for the cabinet. (Joseph Chamberlain). ’ NO STONE UNTURNED The Rt Hon the Lord Heseltine of Thenford CH October 2012 NO STONE UNTURNED in pursuit of GROWTH Contents Overview: One man’s vision 3 Chapter 1: The worst economic crisis of modern times 11 Chapter 2: Localism – building on our strengths 27 Chapter 3: Whitehall – a confident, strategic centre of government 59 Chapter 4: Government and growth – catalyst, enabler, partner 87 Chapter 5: Private sector – broadening the capacity for excellence 121 Chapter 6: Education and skills – the foundation for growth and prosperity 155 Chapter 7: Making it happen 183 Annexes A. Acknowledgements 187 B. Summary of recommendations 202 C. How the system fits together 212 D. Single funding pot 215 E. Illustrative single funding pot bidding framework 218 F. Key elements of a government management information system 221 G. Glossary 225 [ii] NO STONE UNTURNED One man’s vision > our shared responsibility for creating wealth The worst economic crisis of modern times > the scale of the international challenge Localism – building on our strengths > reversing a century of centralisation > enhancing the standing of Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) to bring together partners across the private and public sectors to drive local growth -

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Fat, Disreputable Sir John Falstaff Pursues Two Housewives, Mistress Ford and Mistress Page, Who Outwit and Humiliate Him Instead

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 1 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 2 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 ACT 4 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 5 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

LAND SOUTH of WOOD FORD ROAD, BYFIELD, N ORTHAMPTONSHIRE Residential Travel Plan

LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Residential Travel Plan – Revision A LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan Revision A Revision A Revision – Client: Byfield Medical Centre Engineer: Create Consulting Engineers Ltd ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE 109-112 Temple Chambers Travel Plan 3-7 Temple Avenue London EC4Y 0HA Tel: 020 7822 2300 Email: [email protected] Web: www.createconsultingengineers.co.uk Residential Report By: Fiona Blackley, MA (Hons), MSc, MCIHT, MILT Checked By: Sarah Simpson, BA (Hons), MSc (Eng), CEng, MCIHT Reference: FB/CC/P16-1149/01 Rev A Date: February 2017 LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD OF LAND SOUTH Land South of Woodford Road, Byfield, Northamptonshire, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan LAND SOUTH OF WOODFORD ROAD, BYFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan Revision A Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Policy and Guidance 3.0 Site Assessment 4.0 Proposed Development 5.0 Objectives and Targets 6.0 Travel Plan Measures 7.0 Management and Monitoring 8.0 Disclaimer Appendices A. Bus service 200 timetable B. Northamptonshire Bus Map Registration of Amendments Revision Revision Revision Amendment Details and Date Prepared By Approved By A Updated to include final layout and development details FB SS 21.07.17 Ref: FB/CC/P16-1149/01 Rev A Page 1 Land South of Woodford Road, Byfield, Northamptonshire, NN11 6XD Residential Travel Plan 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Create Consulting Engineers Ltd was instructed by Byfield Medical Centre to prepare a Travel Plan in support of the proposed development on land south of Woodford Road, Byfield, Northamptonshire.