Stormwater Utility Feasibility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

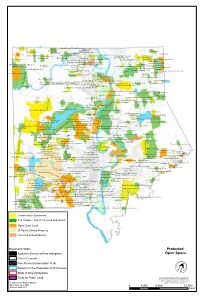

Protected Open Space

Joan and Conrad Hardy Easement Keating Property Weir Road Lot East Street Vacant Lot Weir Road Lot Penacook Park Kattar Subdivision Hyland Property Weir Road Lot Island Pond EstatesVillage Street Gazebo Maxfield Lot Allen State Forest B&M Conservation Land Malinsky Easement Dorthy Walker PropertyReno Easement Foss Easement Freedom Acres Open Space Keller Easement Bulla Property Hardy Property #2 Rolfe Park - LWCF Freedom Acres Open Space Glen Ellen Subdivsion Sally Silver Easement Penacook Street Lot Millstream Open SpaceRolfe Park - LWCF 95 Hoit Road Easement Bois de Brodeur TrustHoit Road Marsh WMA Millsteam Open Space Riley Property Merrimack Valley School District Hoit Road Marsh WMA Woodland Cemetery Laura M Jobin Family Trust Easement Primrose at Penacook Randall Property Emerald Abode Broad Cove Forest Kevin Prince Pines at Hayward BrookAcres of Wildlife Hoit Road Marsh WMA Primrose at Penacook Hoit Road Marsh WMA Emerald Abode Easement Harold Colby Easement Primrose at Penacook rk Riley Property Pa Richards Community Forest Primrose Woods ear Hoit and Shaker Road Easement Primrose Woods Sp k r Riley Property Mast Yard State Forest a P Primrose WoodsPrimrose Woods Manor Dump n Stonehaven e Oxbow Bluffs or Rust Property n i Swan Circle Subdivision t h Horse Hill Road Parcel Oxbow Subdivision Open Space e L Hot Hole Pond Boat Access Sewalls Falls State Recreation AreaFranklin Pierce Property s Carter Hill Road Easement Claremont & Concord RR Bed u G Griffin Easement Contoocook River ParcelClaremont & Concord RR BedB&M Claremont Rail -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES Lakesmart Program

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES LakeSmart Program Only with YOUR help will New Hampshire’s lakes remain clean and healthy, now and in the future. The health of our lakes, and our enjoyment of these irreplaceable natural resources, is at risk. Polluted runoff water from the landscape is washing into our lakes, causing toxic algal blooms that make swimming in lakes unsafe. Failing septic systems and animal waste washed off the land are contributing bacteria to our lakes that can make people and pets who swim in the water sick. Toxic products used in the home, on lawns, and on roadways and driveways are also reaching our lakes, poisoning the water in some areas to the point where fish and other aquatic life cannot survive. NH LAKES has found that most property owners don’t know how their actions affect the health of lakes. We’ve also found that property owners want to do the right thing to help keep the lakes they enjoy clean and healthy and that they often need help of professional service providers like YOU! What is LakeSmart? The LakeSmart program is an education, evaluation, and recognition program that inspires property owners to live in a lake- friendly way, keeping our lakes clean and healthy. The program is free, voluntary, and non-regulatory. Through a confidential evaluation process, property owners receive tailored recommendations about how to implement lake-friendly living practices year-round in their home, on their property, and along and on the lake. Property owners have access to a directory of lake- friendly living service providers to help them adopt lake-friendly living practices. -

Open Space Master Plan

SECTION VII. CONSERVATION AND OPEN SPACE A. INTRODUCTION The Conservation and Open Space Section is intended to guide the protection of the City’s natural resources and environment while promoting the appropriate and efficient use of land and water within the City of Concord in a manner consistent with the economic, physical, and social needs and desires of the citizens of Concord. Appropriate uses of open space have been identified as recreation, public service and safety, resource production, and environmental protection while providing the maximum and multi-purpose use of open space by the citizens of Concord. Open space in Concord is intended to be a system, interconnected and interrelated, and therefore, the links among major open space areas, as well as between the open areas and developed areas, must be defined The Conservation and Open Space Use Section consists of a review of existing protected lands with a focus on additions to the protected land inventory that have occurred since the last Master Plan was adopted in December 1993. Conservation and open space goals are articulated, and applied to and interpreted upon the landscape of the City, and as displayed on maps that indicate how land in Concord should be preserved and protected. Policies and recommendations to guide the implementation of the Future Open Space Plan complete this Section of the Master Plan. B. CONSERVATION AND OPEN SPACE GOALS When the City Council established the Conservation Commission in 1971, it set forth for the Commission the goal of "protecting, promoting and developing the natural resources...and for protecting the watershed resource of the City" and mandated the Conservation Commission, in conjunction with the City Planning Board, to prepare "a conservation and open space plan" as the major objective in achieving this goal, noting that the plan shall be based "on the concept of multiple use of natural resources and open space". -

Merrimack Valley

Aì Im Aì !"`$ ?{ Aù ?x Ij ?¬ ?¬ Im Ai AÔ Aù AÔ ?x ?v !"b$ Ij AÔ AÙ Aä ?¸ !"`$ ?¨ Im AÕ A£ CÚ ?{ ?x A¢ AÖ Ij ?} ?} ?v Il ?} Aõ A¡ ?} Il Ae AÑ ?} AÙ AÑ fg ?¸ ?} ?} Aù Aä !"b$ A¡ !"`$ ?} Ij AÕ A¤ CÓ ?} CÒ Ij ?¸ AÑ ?} ?} C¹ ?{ #V Im Aõ ?¨ AÑ Aý AÙ Ij AÖ fgA B C D AÕ E F G 4 Lake Winnipesaukee d . Merrymeeting Lake Greenough Pond R ALTON BAY STATE FOREST ROLLINS STATE PARK F R A N K L I N 0 K F R A N K L I N B E L M O N T h B E L M O N T e t N 1 9 PAGE STATE FOREST a o . u Sondogardy Pond Aä 8 r r o Crystal Lake 1 th s NNOORRTTHH FFIIEE LLDD N 6 y S O N w a I . R SSAA LLIISS BB UURRYY E GG I O 6 an H r R E t STATE FOREST NURSERY R m Palmer Pond 3 S l i g 4 E S i 3v . K E G e S A K C e L A . N L k 7 n Marsh Pond 3r t 5 1 MEADOW POND STATE FOREST a r . R-11 N Suncook River F R s M o Tucker Pond 1 New Pond MERRIH MACK VALLEY REGION r Chalk Pond 3 r d Stevens Brook AÑ e o 1 t 5 1 h Forest Pond 4 u Lyford Pond . h AYERS STATE FOREST 4 0 Marchs Pond ?§ H e Shellcamp Pond n fg m r S U T T O N B i t n Merrymeeting River S U T T O N g 6 A a d a . -

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records Fall 2014 Vol. 33, No. 3 his issue of New Hampshire Bird Records with its color cover is sponsored by an Tanonymous donor. Thank you! NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS In This Issue VOLUME 33, NUMBER 3 FALL 2014 From the Editor ........................................................................................................................1 Photo Quiz ...............................................................................................................................1 MANAGING EDITOR Fall Season: August 1 through November 30, 2014 ...................................................................2 Rebecca Suomala by Lauren Kras and Ben Griffith 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Concord Nighthawk Migration Study – 2014 Update .............................................................25 by Rob Woodward TEXT EDITOR Field Trip Report – Concord Sparrow Field Trip ......................................................................25 Dan Hubbard by Rob Woodward SEASON EDITORS Fall 2014 New Hampshire Raptor Migration Report ..............................................................26 Eric Masterson, Spring by Iain MacLeod Tony Vazzano, Summer The Life and Death of a Roseate Tern ......................................................................................30 Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall by Stephen R. Mirick Pamela Hunt, Winter Backyard Birder – What is That Strange Bird? Leucism in Birds ..............................................31 LAYOUT by Aiden Moser Kathy McBride Field -

CONSERVATION and OPEN SPACE PLAN UPDATE June 2017

CONCORD CONSERVATION COMMISSION CONSERVATION and OPEN SPACE PLAN UPDATE June 2017 CONCORD, NEW HAMPSHIRE Moosewood Ecological LLC PO Box 9 Chesterfield, NH 03443 (603) 831-1980 [email protected] CONCORD CONSERVATION COMMISSION CONSERVATION and OPEN SPACE PLAN UPDATE CONCORD, NEW HAMPSHIRE Jeffry N. Littleton, M.S. Principal Ecologist Project Manager Moosewood Ecological LLC Chris Kane, M.S. Principal Ecologist Associate Project Manager Kane Conservation Anne Deeley, M.S. GIS Specialist Neatline Associates Carol Ogilvie, M.A. Land Use Planning Consultant Moosewood Ecological LLC Innovative Conservation Solutions for New England PO Box 9 Chesterfield, NH 03443-0009 (603) 831-1980 [email protected] www.moosewoodecological.com June 2017 Cover photograph – The Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) is both a federally and state-endangered species that occurs in the pine barrens of Concord. Photo by Ben Kimball Preface The City of Concord’s Conservation Commission is pleased to present its Conservation and Open Space Plan. The creation of such a plan is part of the original mandate to the Conservation Commission when the Commission was created by the Concord City Council in 1971. The Commission’s first such plan, and the many updates that have followed, have guided and informed the Commission’s efforts in meeting the goals established for it by the City Council. This updated Conservation and Open Space Plan is intended to serve as an addendum to the Conservation and Open Space section of the City’s Master Plan 2030, which was adopted in 2008. That section of the Master Plan is intended to guide the protection of the City’s natural resources and the environment while promoting the appropriate and efficient use of land and water within the City in a manner consistent with the economic, physical, and social needs and desires of the citizens of Concord. -

New Hampshire!

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department NEW HAMPSHIRE FRESHWATER FISHING 2021 DIGEST Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2021 Go Fish New Hampshire! Nearly 1,000 fishable lakes and 12,000 miles of rivers and streams… The Official New Hampshire fishnh.com Digest of Regulations Why Smoker Craft? It takes a true fisherman to know what makes a better fishing experience. That’s why we’re constantly taking things to the next level with design, engineering and construction that deliver best-in-class aluminum fishing boats for every budget. \\Pro Angler: \\Voyager: Grab Your Friends and Head for the Water Years of Worry-Free Reliability More boat for your bucks. The Smoker Craft Pro Angler The Voyager is perfect for the no-nonsense angler. aluminum fishing boat series leads the way with This spacious and deep boat is perfect for the first feature-packed value. time boat buyer or a seasoned veteran who is looking for a solid utility boat. Laconia Alton Bay Hudson 958 Union Ave., PO Box 6145, 396 Main Street 261 Derry Road Route 102 Laconia, NH 03246 Alton Bay, NH 03810 Hudson, NH 03051 603-524-6661 603-875-8848 603-595-7995 www.irwinmarine.com Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2021 NEW HAMPSHIRE Fish and Game Department FRESHWATER FISHING 2021 DIGEST Lakes and Rivers Galore I am new to Fish and Game, but I was born and raised in New Hampshire and have spent a lifetime working in the outdoors of our Granite State. I grew up with my friends ice fishing for lake trout and cusk on the hard waters of Lake Winnipesaukee and Lake Winnisquam with my father and his friends. -

Fall 2012 Vol. 31 No. 3

V31 N3 Fall-12_v3 8/17/13 5:01 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Fall 2012 Vol. 31, No. 3 V31 N3 Fall-12_v3 8/17/13 5:01 PM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 31, Number 3 Fall 2012 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Eric Masterson, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall; Pamela Hunt, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Zeke Cornell, David Deifik, Margot Johnson, Elizabeth Levy, Susan MacLeod, Aiden Moser, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Tony Vazzano, Phyllis Yaffie Field Notes: Robert A. Quinn Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Ed Larrabee Web Master: Kathy Barnes Where to Bird: Phil Brown Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Ben Griffith, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Lauren Kras, Ed Larrabee, Iain MacLeod, Eric Masterson, Robert A. Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Say’s Phoebe by Jason Lambert, 11/22/12, Penacook (Concord), NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Thank you to the many observers who submit their sightings to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh), the source of data for this publication. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typi- cally represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publi- cation of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. -

Lakes Region

Aú Aè ?« Aà Kq ?¨ Aè Aª Ij Cã !"b$ V# ?¨ ?{ V# ?¬ V# Aà ?¬ V# # VV# V# V# Kq Aà A© V# V# Aê !"a$ V# V# V# V# V# V# V# ?¨ V# Kq V# V# V# Aà C° V# V# V# V#V# ?¬A B C D V# E F G 9.6 V#Mount Passaconaway Kq BAKERAê RIVER 10.0 Saco River WARRENWARREN 9.2 Mount Paugus Mount Chocorua 0.9 NH 25A 0.2 Peaked Hill Pond Ij Mad River Mount Whiteface V# ?Ã Noon0 Peak 2.5 5 10 V# Pequawket Pond CONWAY Mud Pond V# CONWAY ELLSWORTHELLSWORTH Aj JenningsV# Peak ?¨Iona Lake Cone Pond MilesALBANYALBANY Conway Lake LAKES REGIONNH 175 THORNTONTHORNTON WHITE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL FOREST Ellsworth Pond WATERVILLEWATERVILLEV# VALLEYVALLEY Upper Pequawket Pond Flat Mountain Ponds Snake Pond WENTWORTHWENTWORTH US 3 Sandwich MountainSandwich Dome Ledge Pond WW H H I I T T E E MM O O U U N N T T A A I I N N RR E E G G I I O O N N Whitton Pond BICYCLE ROUTES V# Haunted Pond Dollof Pond 1 I NH 49 Middle Pea Porridge Pond 1 27 Pea Porridge Pond Ae ")29 13.4 Labrador Pond 4.0 ?{ 34 Atwood Pond Aá 8.6 Campton Pond Black Mtn Pond Lonely Lake Davis Pond Tilton Pond Câ James Pond 14.1 Chinook Trail South Branch Moosilauke Rd 13.0 2.1 Chase Rd Chocorua Lake RUMNEYRUMNEY 2.8 ")28 Great Hill Pond fg Tyler Bog Roberts Pond 2.0 Guinea Pond Little Lake Blue PondMADISONMADISON R-5 4.2 HEMMENWAY STATE FOREST Mack Pond Loud Pond NH 118 Pemigewasset River 5.1 Mailly Pond Drew Pond 3.7 fg Buffalo Rd CAMPTON Hatch PondEATONEATON 5.3 CAMPTON Baker River Silver Pond Beebe River ?¬ Quincy Rd Chocorua Rd DORCHESTERDORCHESTER 27 0.8 Durgin Pond ") SANDWICHSANDWICH 4.5 Loon Lake BLAIR STATE -

The Industrial Utility of Public Water Supplies in the New England States, 1952

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 288 THE INDUSTRIAL UTILITY OF PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES IN THE NEW ENGLAND STATES, 1952 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CffiCULAR 288 THE INDUSTRIAL UTILITY OF PUBLIC WATER SUPPLIES IN THE NEW ENGLAND STATES, 1952 By E. W. Lobr and W. F. White Washington. D. C., 1953 Free on application to the GeJogical Survey, Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Introduction • . • • . • . • . • • . • • • • • • • • 1 Massachusetts--Continued • • . • • 28-56 Connecticut ••••••••..•....••..• 3-16 Braintree town •.........•• , . • . 28 Bridgeport • . • • . • • . • • • • • • • • 3 Brockton • . • • . • . • • . • . 29 Bristol . • • • • • . • • . • . • • • • . • . • 4 Brookline town • . • . • . • . • • • • . • 29 East Hartford town ••.. o....... 4 Ca.Illnridge • . • . • • • . • . • . 30 Fairfield town " • . • • . • . • • . 4 Chelsea • • . • . • • •. • . • . • • • • 31 Greenwich town •• o • • • • • • • • • • • • 5 Chicopee • • • • • . • • • • . • . • • • • • • • • 31 Hamden town • • • • . • • . • . • • • • • . • • 5 Everett • • • • • • • • • . • • . • • • • • . • 31 Hartford. • . • • . • • • . • • • • . 6 Fall River • • • • . • . • • . • • . • 3 2 Middletown ...•••••.•.• ~ • . • • • . 7 Fitchburg . • . • . • • • . • • • . • . 33 Milford town . • . • • • • • . • . • • • • . • 7 Framingham town • • • • • • • . • 34 New Britain. • • . • • • . • • . • . • . 8-9 Gloucester. • . • • . • • . • . • . • • 3 5 New Haven .••.... o........ 10-11 Haverhill -

New Hampshire!

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department NEW HAMPSHIRE FRESHWATER FISHING 2018 DIGEST Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2018 Go Fish New Hampshire! Nearly 1,000 fishable lakes and 12,000 miles of rivers and streams… The Official New Hampshire fishnh.com Digest of Regulations IRW_NHFishGuide_Oct17.indd 1 10/20/17 12:04 PM Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2018 NEW HAMPSHIRE Fish and Game Department FRESHWATER FISHING 2018 DIGEST Fish New Hampshire and Relax Greetings, anglers! With 12,000 miles of rivers and streams and 975 lakes and ponds in New Hampshire, you are never far from great fishing – and the relaxation and magnificent scenery that go with it. Angling adventures here are as diverse as the state itself. You can target wild brookies in our mountain streams, bring in a big bass or lake trout in the Lakes Region, or head for the mighty Connecticut River, with a dozen or more different species of fish. For your fishing pleasure, we stock nearly a million ON THE COVER: rainbow, brook and brown trout, as well as landlocked salmon every year. Check Landing a trout. out locations in the stocking reports on our mobile-friendly website at fishnh.com. (© iStock.com/doug4537) New Hampshire’s strong warmwater fisheries, from bass, pike, and pickerel to perch, pumpkinseeds, and crappie, offer action-packed adventure, as well. New Hampshire fishing licenses are one of the best deals around. You get a full year of outdoor recreation, fish for dinner if you’re successful, and the knowledge that you’re supporting the work that conserves the resource and makes these opportunities available for you and future generations.