Migrant Pronunciation: What Do Employers Find Acceptable?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alma's Good Trip Mikko Joensuu in Holy Water Hippie Queen of Design Frank Ocean of Love Secret Ingredients T H Is Is T H E M

FLOW MAGAZINE THIS IS THE MAGAZINE OF FLOW FESTIVAL. FESTIVAL. FLOW OF IS THE MAGAZINE THIS ALMA'S GOOD TRIP MIKKO JOENSUU IN HOLY WATER HIPPIE QUEEN OF DESIGN FRANK OCEAN OF LOVE SECRET INGREDIENTS F entrance L 7 OW F L O W the new This is 1 to 0 2 2 0 1 7 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6–9 12–13 18–21 36–37 Editor 7 7 W Tero Kartastenpää POOL OF ALMA Alma: ”We never really traveled when we were Art Director little. Our parents are both on disability Double Happiness pension and we didn’t IN SHORT have loads of money. Swimming with a Whenever our classmates Designers singer-songwriter. traveled to Thailand Featuring Mikko MINT MYSTERY SOLVED or Tenerife for winter Viivi Prokofjev SHH Joensuu. holidays we took a cruise AIGHT, LOOK to Tallinn. When me and Antti Grundstén 22–27 Anna turned eighteen we Frank Ocean sings about Robynne Redgrave traveled to London with love and God and God and our friends. We stayed for love. Here's what you didn’t five days, drunk.” 40–41 Subeditor know about alt-country star Ryan Adams. Aurora Rämö Alma went to L.A. and 14–15 met everybody. Publisher 34–37 O The design hippie Laura Flow Festival Ltd. 1 1 Väinölä creates a flower ALWAYS altar for yoga people. Lana Del Rey’s American Contributors nightmares, plant cutting 30–33 Hanna Anonen craze, the smallest talk etc. The most quiet places OCEAN OF TWO LOVES Maija Astikainen from abandoned villas to Pauliina Holma Balloon stage finds new UNKNOWN forgotten museums. -

DAVID RYAN ADAMS C/O PAX-AM Hollywood CA 90028

DAVID RYAN ADAMS c/o PAX-AM Hollywood CA 90028 COMPETENCIES & SKILLS Design and construction of PAX-AM studios in Los Angeles to serve as home of self-owned-and-operated PAX-AM label and home base for all things PAX-AM. Securing of numerous Grammy nominations with zero wins as recently as Best Rock Album for eponymous 2014 LP and Best Rock Song for that record's "Gimme Something Good," including 2011's Ashes & Fire, and going back all the way to 2002 for Gold and "New York, New York" among others. Production of albums for Jenny Lewis, La Sera, Fall Out Boy, Willie Nelson, Jesse Malin, and collaborations with Norah Jones, America, Cowboy Junkies, Beth Orton and many others. RELEVANT EXPERIENCE October 2015 - First music guest on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah; Opened Jimmy Kimmel Live's week of shows airing from New York, playing (of course) "Welcome To New York" from 1989, the song for song interpretation of Taylor Swift's album of the same name. September 2015 - 1989 released to equal measures of confusion and acclaim: "Ryan Adams transforms Taylor Swift's 1989 into a melancholy masterpiece... decidedly free of irony or shtick" (AV Club); "There's nothing ironic or tossed off about Adams' interpretations. By stripping all 13 tracks of their pony-stomp synths and high-gloss studio sheen, he reveals the bones of what are essentially timeless, genre-less songs... brings two divergent artists together in smart, unexpected ways, and somehow manages to reveal the best of both of them" (Entertainment Weekly); "Adams's version of '1989' is more earnest and, in its way, sincere and sentimental than the original" (The New Yorker); "the universality of great songwriting shines through" (Billboard). -

1 2 | Lonestarmusic Lonestarmusic | 3

LoneStarMusic | 1 2 | LoneStarMusic LoneStarMusic | 3 inside this issue SHOVELS AND ROPE pg 38 O’ What Two Can Do The triumphant union, joyful noise and crazy good times of Cary Ann Hearst and Michael Trent by Kelly Dearmore FEATUREs 34 Q&A: Paul Thorn — By Lynne Margolis 48 Sunny Sweeney finds the light — By Holly Gleason 52 Lee Ann Womack: When I come around — By Richard Skanse 56 Cory Branan: The wandering musical spirit of Americana’s free-ranging “No-Hit Wonder” — By Adam Daswon 58 Imagine Houston: An excerpt from Reverb, the new novel by Joe Ely Photo courtesy of All Eyes Media 4 | LoneStarMusic LoneStarMusic | 5 after awhile inside this issue Publisher: Zach Jennings Editor: Richard Skanse Notes from the Editor | By Richard Skanse Creative Director/Layout: Melissa Webb Cover Design: Melissa Webb Advertising/Marketing: Kristen Townsend Apart from the opportunity to work with a team of really good people Advertising: Tara Staglik, Erica — especially graphic designer Melissa Webb, who I’d already known and Brown greatly respected for years — one of the things that appealed most to me Artist & Label Relations: Kristen Townsend about joining this magazine five years ago was owner Zach Jennings’ vision that LoneStarMusic could be about more than just Texas music. Even more Contributing Contributing and Writers Photographers than Texas Red Dirt music. We all agreed that we would still focus on songwriters and roots and/or country(ish) music — pretty much anything Richard Skanse John Carrico that could directly or even indirectly fall under the category of “Americana” in Lynne Margolis Lynne Margolis Brian T. -

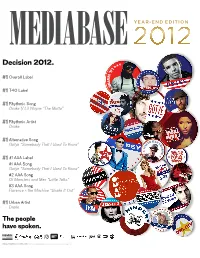

Decision 2012

YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 Decision 2012. #1 Overall Label #1 T40 Label #1 Rhythmic Song Drake f/ Lil Wayne “The Motto” #1 Rhythmic Artist Drake Alternative Song #1 HAW ER T Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” Y H A O M R N H E H #1 #1 AAA Label #1 AAA Song Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” #2 AAA Song Of Monsters and Men “Little Talks” #3 AAA Song Florence + the Machine “Shake It Out” #1 Urban Artist Drake The people have spoken. www.republicrecords.com c 2012 Universal Republic Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. REPUBLIC LANDS TOP SPOT OVERALL Republic Top 40 Champ Island Def Jam Takes Rhythmic & Urban Republic t o o k t h e t o p s p o t f o r t h e 2 0 1 2 c h a r t y e a r, w h i c h w e n t f r o m N o v e m b e r 2 0 , 2 0 1 1 - N o v e m b e r 17, 2012. The label was also #1 at Top 40 and Triple A, while finishing #2 at Rhythmic, #3 at Urban, and #4 at AC. Their overall share was 13.5%. Leading the way for Republic was newcomer Gotye, who had one of the year’s biggest hits with “Somebody That I Used To Know.” A big year from Drake and Nicki Minaj also contributed to the label’s success, as well as strong performances for Florence + The Machine, Volbeat, and Of Monsters And Men to name a few. -

Current, September 08, 2014 University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 9-8-2014 Current, September 08, 2014 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, September 08, 2014" (2014). Current (2010s). 175. http://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/175 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. 48 ISSUE 1445 The Current SEPT 15, 2014 UMSL’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWS Meal plans mandated for residents CULLEN WILLIAMS STAFF WRITER While the University of Missouri – St. Louis is seen as mostly a commuter school, roughly 1,000 students chose to live on campus. The campus has a number of residential halls and apartments, but for those who live in either Oak Hall or Villa Hall this means a mandatory meal plan, with the exception of Honors Living Community in Villa Hall. The meal plans range from $1599-$1840 per semester, depending on which option the student purchases. The current meal plan options were put in place after Sodexo, an international food services company, was awarded a five year contract with UMSL, which started in January of 2011. The meal LORI DRESNER /THE CURRENT plan options available for lower classmen are as listed The Nosh, MSC’s food court of north campus below: Option 1: 100 meal blocks to purchase a meal plan in residential halls had adequate Bros. -

September 15, 2014

VO l. 48 ISSUE 1445 SEPT 15, 2014 UMSL'S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWS Meal plans mandated for residents CULLEN WILLIAMS STAFF WRITER While the University of Missouri - St. Louis .is seen as mostly a commuter school, roughly 1,000 students chose to live on campus. The campus has a number of residential halls and apartments, but for those who live in either Oak Hall or Villa Hall this means a mandatory meal plan, with the exception of Honors Living Community in Villa Hall. The meal plans range from $1599-$1840 per semester, depending on which option the student purchases. The current meal plan options were put in place after Sodexo, an international food services company, was awarded a five year contract with UMSL, which started in January of 20 II . The meal pl:lll options available {or lower classmen 3:e as listed "tM Nosh. M5C.'s food court ot north campus bdow: Option 1: 100 meal blocks to purchase a meal plan in residential halls had adequare Bros. Bagels in the Millennium blocks] get chopped off, which with a $350 declining balance order to live on campus. cooking space for the students. Student Center. However, is really frustrating." ($ 1599 per semester) Ac<cording to Gary Prellwitz, Once students have been the meal block can only be Another student, Oprion 2: ISO meal blocks general manager with Sodexo, set up with a meal plan, they used rwice per day, Monday Marcus Scimio. freshman, enginee rin g, stated, "Yeah, I with a $250 declining balance these plans are mandatory are able to use their card in at a through Thursday from 10:30 would like to see a plan for ($ 1790 per semester) because, "Those facilities are variety of locations, including a.m. -

The Titles Below Are Being Released Exclusively For

THE TITLES BELOW ARE BEING RELEASED EXCLUSIVELY FOR RECORD STORE DAY (v1.00 updated 3-9-15) FORM HOW ARTIST TITLE LABEL AT MANY? ! 311 Grifter/Who's Got The Herb? Legacy 7" 1890 ! The 1975 Facedown EP Interscope 12" 2000 ! The 1975 Sex EP Interscope 12" 2000 ! The 1975 Music For Cars Interscope 12" 2000 ! The 1975 IV EP Interscope 12" 2000 ! Bernard Herrmann Psycho Music on Vinyl 7" 2000 ! Larry Young Selections from Larry Young in Paris - ResonanceThe ORTF Recordings 10" 1200 ! 101ers Elgin Avenue Breakdown Rhino 2 x 12" 5500 ! a-ha Take On Me Rhino 7" 3000 ! A$AP Rocky LPFJ2 RCA 7" 2500 ! Adam & The Ants Kings of the Wild Frontier/Ant Music Legacy 7" 2000 ! Ryan Adams Come Pick Me Up Pax-Am 7" 7000 ! Air Playground Love Rhino 7" 5000 ! Gregg Allman Gregg Allman Concord 10" picture disc 3500 ! Amanaz Africa Now-Again Records 2 x 12" 2000 ! The Animals We're Gonna Howl Tonight Rhythm and Blues 12" 1200 ! The Animals The Animals No. 2 ABKCO 10" 3900 ! At The Gates Gardens of Grief Century Media 12" 1500 ! Chet Atkins My Brother Sings Sundazed Music 12" 2000 ! Atreyu So Others May Live Spinefarm 7" 1700 ! Avivii The Days/Nights Remix EP Island 12" 1300 ! BANKS The Remixes Part 2 Harvest 12" 2000 ! Jeff Beck Love is Blue/I've Been Drinking Sundazed Music 7" 2000 ! Jeff Beck Hi Ho Silver Lining/Beck's Bolero Sundazed Music 7" 2000 ! Jeff Beck Tallyman/Rock My Plimsoul Sundazed Music 7" 2000 ! Bee Gees Extended Rhno 12" 3000 ! Big Data Dangerous Warner Bros. -

CD Review: Able Thought’S Serene in Limbo

CD Review: Able Thought’s serene In Limbo Local one-man band Able Thought brings a dose of tranquility to the Providence music scene with his latest album, serene In Limbo. People like Andrew Bird and Kishi Bashi have made looping an art form and removed the need for a backing band to produce a full sound. Able Thought uses a loop pedal — I’m assuming — to create his own brand of atmospheric, low-fi folk. What’s striking on first-listen is the use of a nylon string classical guitar as a specific choice. Where folk musicians usually swear by the metal strings, Able Thought embraces the nylon, giving serene In Limbo a signature sound. The guitar playing sounds like a mix of fingerstyle and traditional picking that works well, especially in songs like “In Limbo” and “Places.” But the ambient quality that attracts people to this kind of music has a way of mashing the songs together and making it hard to differentiate one from the next. The level of manipulation makes me wonder if they’d be recognizable played with no effects. To be fair, this gripe is more of a comment on the musical style; I have been accused of not being able to enjoy “chill” music, but many artists these days seem to be drowning themselves in ever-increasing levels of reverb. Maybe the best way to describe the sound is by simply recalling the name of the album. You feel like you’re floating in limbo in some echo-y, open forest. With tons of reverb. -

FATIMA WASHINGTON on Songwriting, an Hour Each Day Practicing Guitar and an Hour Or Bowie’S Influence Mellows MTH out a Little on This Record, More Each Day Singing

-----------------------------------------Spins --------------------------------------- Wooden Nickel Ryan Adams CD of the Week Ashes & Fire BACKTRACKS Now a sober man with a Hol- Mott the Hoople lywood wife, a Hollywood house and All the Young Dudes (1972) his own record label, Pax Am, Ryan Adams has released the first record When Mott the Hoople members of his second act, a mellow and warm were trying to figure out the direction singer/songwriter effort called Ashes of the band (and its fifth record), along & Fire. The two things you’re bound came glam-rocker David Bowie. Bowie to hear about this record, if you’re the penned the title track and produced an investigative type, is that: (1) The record is quite mellow and feels album that would save the careers of Ian like something of a brother to Neil Young’s Harvest and After the Hunter and the rest of MTH. It would become one of the most Goldrush; and 2) Adams has become, maybe above all else, an in- recognizable songs in rock n’ roll. credible vocalist. Opening with Lou Reed’s “Sweet Jane,” MTH cover this clas- In a 2001 interview, following the release of his make-or-break sic with a happier vibe and a progressive, almost Calypso beat. $9.99 sophomore solo release, Gold, Adams spoke about his then-strict “Momma’s Little Jewel” has a fat piano arrangement and some routine, where he forced himself to spend an hour each day working horns and “Sucker” has that early, glam-Euro rock of the 1970s. FATIMA WASHINGTON on songwriting, an hour each day practicing guitar and an hour or Bowie’s influence mellows MTH out a little on this record, more each day singing. -

LEBENSLAUF DAVID RYAN ADAMS C/O PAX-AM Hollywood CA 90028

LEBENSLAUF DAVID RYAN ADAMS c/o PAX-AM Hollywood CA 90028 BERUFLICHE ZIELE Veröffentlichung des selbstproduzierten neuen Albums „Ryan Adams“ am 5. September bei PAX- AM/Blue Note, sowie die Live-Präsentation des besagten Albums bis ins Jahr 2015 hinein. KOMPETENZEN UND FÄHIGKEITEN Entwurf und Aufbau der PAX-AM-Studios in Los Angeles als Sitz des selbst-betriebenen Labels PAX- AM, das sich um alle PAX-AM-Angelegenheiten kümmert; dazu gehört die Veröffentlichung einer neuen Single-Reihe. Der Verantwortungsbereich als Besitzer und Betreiber beinhaltet unter anderem das Produzieren von Aufnahmen anderer Künstler, darunter Jenny Lewis und Fall Out Boy. Zahlreiche Grammy-Nominierungen, ohne dabei aber jemals tatsächlich zu gewinnen. Zu den Nominierungen gehören unter anderem das Album Ashes & Fire aus dem Jahr 2011, aber auch frühe Werke wie Gold und „New York, New York“. BERUFSERFAHRUNG September 2013 bis heute - Ryan Adams – Das neue Album ist das erste, das im Rahmen der neugegründeten Kooperation zwischen PAX-AM und Blue Note entsteht – elf neue Songs, angeführt von „Gimme Something Good“, der ersten Vinyl-Single, die Platz 1 des Amazon.com-Musicstores erreichte. „Gimme Something Good“ steht auf der Empfehlungsliste von Entertainment Weekly („besticht mit dem Draufgängertum der Stones und einem Refrain, der die Arme in die Luft reißt“). Lob gibt es außerdem von Time („ein rauer, gitarrenlastiger Sound, der sich perfekt dazu eignet, im Sommer bei aufgedrehter Anlage durch die Stadt zu cruisen... beweist Adams Talent dafür, intim klingenden Stadion-Rock zu spielen“), von Stereogum („er scheint beim Schreiben dieses Songs nichts ausgelassen zu haben. Das Stück ist der absolute Hammer“) und anderen. -

Maitri Marks 25 Years

5 13 21 AIDS grove helps AEF Gay Romney aide quits SF Ballet's 'Don Quixote' The www.ebar.com Serving the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender communities since 1971 Vol. 42 • No. 18 • May 3-9, 2012 Maitri Trans woman killed in Oakland by Seth Hemmelgarn akland police are investigating the marks shooting death of a transsexual Owoman who was killed in her car in the city’s downtown area Sunday morning, 25 years April 29. A woman who was with the victim, Brandy by Seth Hemmelgarn Martell, 37, said that she was killed shortly after a man Martell had been talking to learned of aitri, a San Francisco nonprofi t her gender identity. that provides services to people Oakland Police Department spokeswoman Mliving with HIV and AIDS who Lea Rubio said that at 5:16 a.m. Sunday, police are in need of either responded to the 400 block of 13th Street, near hospice care or 24- Franklin Street. Offi cers located Milton Massey hour nursing care, is Jr., which police say is Martell’s legal name, in- marking its 25th an- side a vehicle, she said. Martell, which someone niversary this year. who knew her said was her legal name, was The agency, which pronounced dead at the scene. Investigators are is at 401 Duboce looking into the motive for the shooting, said Avenue, will hold its Oakland police cordoned off an area downtown before Rubio. Brandy Martell’s body was removed by coroner’s off icials. annual Bliss gala this Bryana Coleman, 37, who’s transgender and weekend. -

Quiet American

COVER STORY Inner ear problems mean the prolific Ryan Adams prefers to turn the volume down. By Tim Hume QUIET AMERICAN For the past few years, Ryan Adams, the wildly years of largely self-inflicted turmoil. The one-time of tinnitus that goes with it, which for me plays out gifted, perennially under-delivering poster boy of hellraiser, who used to boast of doing speedballs – like an extremely loud car engine or a screaming alt-country, has been on a break. Not that anyone a volatile cocktail of cocaine and heroin – on a daily siren in my left ear that doesn’t stop for a week. would have noticed. Having announced, in early basis, now finds even espresso too rich for his The psychological pain of dealing with that sound is 2009, an indefinite leave of absence from the blood. Having abandoned the demi-monde of his maddening and frustrating. You just want it to f...ing “soul destroying” music industry, the spiky North adopted New York City, he’s more likely these days stop, and it doesn’t.” Carolina native went on to unearth two records to be found hiking in the California mountains with While he had been sober for a few years, his from his vaults last year, one a double album. his wife, the pop idol turned Hollywood sweetheart Meniere’s diagnosis in 2007 required him to expand Releasing 47 new tracks on his year off – including Mandy Moore, about whom, his PR minders are his clean living regime. He quit smoking, changed a wilfully niche “sci-fi metal concept album” – did adamant, he will take no questions.