The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Our Collective Nightmare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hell on Earth… Alex

Bulletin of the Kate Sharpley Library 02:2000 No21 $1/50p Hell on Earth… Alex. Berkman’s first speech after his release from Alexanderjail Berkman was released from prison on May Sheriff, “he can speak half a dozen languages”. Then 18, and went direct to Detroit, Mich., where he the officer of the workhouse came up to me and said; delivered the following address on May 22: “young man, let me tell you something: we only speak I suppose you have heard the story about the one language here, and damn little at that.” Under such little boy who was asked one day by his mother circumstances you will understand that I am somewhat whether he had said his morning prayer, and little out of practice: in fact, I have almost forgotten how to Johnny replied that he had, and then asked: “Mother, talk at all. And, therefore, I am not going to make a why is it my prayer is so long? Mary is such a big girl, so•called speech to you tonight, but I just want to talk and she has only got a little prayer”. His mother said, to you a little. “why, Johnny, how’s that?” and then the little boy told First of all, I want to tell you how glad I am to her that when Mary was called in the morning she be again in your midst. And you, my friends, are prayed like this: “Oh, Lord. I hate to get up.” That’s evidently pleased to see me, but, great as your pleasure how I felt when my name was called. -

Altus Rop Temp

197714 News-GThe Grayson County azette • GRAYSON COUNTY’S FULL-COVERAGE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER • SATURDAY,OCTOBER 15, 2011 • IN OUR 119TH YEAR • 75 CENTS NEWS STAND, 25 CENTS DELIVERED 40 PUBLIC SQUARE., LEITCHFIELD,KY.•COPYRIGHT 2009 • 270.259.9622 • www.gcnewsgazette.com • Vol. 130, Issue 079 Beshear campaign coming to county Grayson BY REBECCA MORRIS several other Democratic candidates will be include Bowling Green, Morgantown and Reporter embarking on a two-week bus tour of the Hartford. [email protected] state starting Sunday, Oct. 16. While Steve Beshear isn’t expected to County Tea The campaign’s bus tour is expected to attend the Leitchfield event, his wife Jane is, The Beshear/Abramson campaign is arrive in Leitchfield at 5:30 p.m. Tuesday, along with former Louisville mayor scheduled to make a stop in Grayson County Oct. 25, at the former Sonic restaurant build- Abramson, Treasurer Todd Hollenbach, state Party forms later this month. ing on South Main Street. auditor candidate Adam Edelen, and agricul- BY REBECCA MORRIS The Kentucky Democratic Party Leitchfield is the last stop in a swing ture commissioner candidate Robert Farmer. Reporter announced Thursday that governor Steve through south-central Kentucky. Other The two-week campaign swing is being [email protected] Beshear, running mate Jerry Abramson and towns the campaign is visiting that day called the “Tested, Trusted, Tough,” tour. A Grayson County chapter of the Tea Party next week will hold the first of what are expected to become regular meetings. Local boys become racing legends The group will meet at 6 p.m. -

Finn Ballard: No Trespassing: the Post-Millennial

Page 15 No Trespassing: The postmillennial roadhorror movie Finn Ballard Since the turn of the century, there has been released throughout America and Europe a spate of films unified by the same basic plotline: a group of teenagers go roadtripping into the wilderness, and are summarily slaughtered by locals. These films may collectively be termed ‘roadhorror’, due to their blurring of the aesthetic of the road movie with the tension and gore of horror cinema. The thematic of this subgenre has long been established in fiction; from the earliest oral lore, there has been evident a preoccupation with the potential terror of inadvertently trespassing into a hostile environment. This was a particular concern of the folkloric Warnmärchen or ‘warning tale’ of medieval Europe, which educated both children and adults of the dangers of straying into the wilderness. Pioneers carried such tales to the fledging United States, but in a nation conceptualised by progress, by the shining of light upon darkness and the pushing back of frontiers, the fear of the wilderness was diminished in impact. In more recent history, the development of the automobile consolidated the joint American traditions of mobility and discovery, as the leisure activity of the road trip became popular. The wilderness therefore became a source of fascination rather than fear, and the road trip became a transcendental voyage of discovery and of escape from the urban, made fashionable by writers such as Jack Kerouac and by those filmmakers such as Dennis Hopper ( Easy Rider, 1969) who influenced the evolution of the American road movie. -

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

Movie Database

Integrated Movie Database Group 9: Muhammad Rizwan Saeed Santhoshi Priyanka Gooty Agraharam Ran Ao Outline • Background • Project Description • Demo • Conclusion 2 Background • Semantic Web – Gives meaning to data • Ontologies – Concepts – Relationships – Attributes • Benefits 3 Background • Semantic Web – Gives meaning to data • Ontologies – Concepts – Relationships – Attributes • Benefits – Facilitates organization, integration and retrieval of data 4 Project Description • Integrated Movie Database Movies Querying Books RDF Repository People 5 Project Description • Integrated Movie Database – Project Phases • Data Acquisition • Data Modeling • Data Linking • Querying 6 Data Acquisition • Datasets – IMDB.com – BoxOfficeMojo.com – RottenTomatoes.com – Wikipedia.org – GoodReads.com • Java based crawlers using jsoup library 7 Data Acquisition: Challenge • Crawlers require a list of URLs to extract data from. • How to generate a set of URLs for the crawler? – User-created movie list on IMDB • Can be exported via CSV – DBpedia 1. Using foaf:isPrimaryTopicOf of dbo:Film or schema:Movie classes to get corresponding Wikipedia Page. 2. Crawl Wikipedia Page to get IMDB and RottenTomatoes link 8 Data Acquisition: IMDB • Crawled 4 types of pages – Main Page • Title, Release Date, Genre, MPAA Rating, IMDB User Rating – Casting • List of Cast Members (Actors/Actresses) – Critics • Metacritic Score – Awards • List of Academy Awards (won) – Records generated for 36,549 movies – Casting Records generated: 856,407 9 Data Acquisition: BoxOfficeMojo • BoxOfficeMojo -

Montclair Film Announces October 2017 Lineup at Cinema505

! For Immediate Release MONTCLAIR FILM ANNOUNCES CINEMA505 PROGRAM FOR OCTOBER 2017 SLASHERS! retrospective arrives for Halloween September 22, 2017, MONTCLAIR, NJ - Montclair Film today announced the complete October 2017 film lineup for Cinema505, the organization’s screening space located in the Investors Bank Film & Media Center at 505 Bloomfield in Montclair, NJ. October marks the continuation of the ongoing Montclair Film + Classics series, this time featur- ing SLASHERS!, a retrospective program of the horror genre’s touchstone films, all pre- sented on the big screen, including the 4K restoration of Tobe Hooper’s THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE, the restored version of John Carpenter’s HALLOWEEN, and more. October also sees the continuation of The Mastery of Miyazaki series, which fea- tures the Japanese animation legend’s all ages classic PONYO, presented in English for the enjoyment of younger children. October will also see runs of the critically acclaimed new documentary releases THE FORCE, directed by Peter Nicks, EX LIBRIS: NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY, a masterful portrait of the New York Public Library directed by documentary film legend Frederick Wiseman, Jeff Malmberg and Chris Shellen's Montclair Film Festival hit SPETTACOLO returns, THE PARIS OPERA, a wonderful documentary about the legendary Parisian the- ater directed by Jean-Stéphane Bron, and REVOLUTION ’67 directed by Jerome + Mary- lou Bongiorno features in Filmmakers Local 505 program, a look at the 1967 Revolution in Newark, NJ. The Films October 4-8, THE FORCE, directed by Peter Nicks October 6-8, EX LIBRIS: NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY, directed by Frederick Wiseman October 7 & 8, SCREAM, directed by Wes Craven October 11-15, HALLOWEEN, directed by John Carpenter October 13-15, FRIDAY THE 13TH, directed by Sean S. -

Doctor Extraño: Marvel Lo Ha Vuelto a Lograr ¡Por Fin! Por Fin Marvel

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 26, nº2 (2016) · ISSN: 2014-668X altura de Iron Man o Los Vengadores — véase los casos de Vengadores: La era de Ultrón o Capitán América: Civil War, y un Ant-Man, que aunque muy divertido, se notaba que estaba hecho a medias—, y ahora ha cogido un personaje nuevo para el Universo Cinematográfico, tan desconocido para el gran público como lo fueron los Guardianes de la Galaxia, y han conseguido hacer un auténtico peliculón… Bueno, un auténtico peliculón dentro de los cánones de Marvel. Sin entrar en demasiados detalles, ya que esta es una película para descubrir en las salas, la historia gira en torno al Dr. Stephen Strange, un neurocirujano obsesionado en su ego como gran médico, y que solo se preocupa por los casos que le pueden reportar un éxito tan tangible como su Doctor Extraño: Marvel lo ha vuelto a ático, su colección de relojes o sus lograr deportivos. Pero todo cambia cuando sufre un terrible accidente que le Por FRANCESC MARÍ COMPANY destroza sus manos y, aunque trata por todos los medios recuperar sus preciadas ¡Por fin! Por fin Marvel Studios herramientas de trabajo, descubre que ha hecho lo que tenía que hacer. nunca más volverá a operar. Salvando todas las diferencias Desesperado decide seguir la misteriosa argumentales, Doctor Extraño es como pista de Kamar-Taj, en Nepal, un lugar Guardianes de la Galaxia. Me explico: en el que alguien supuestamente puede después de unas cuantas películas, que si recuperarse mágicamente de durísimas bien no eran malas, tampoco estaban a la lesiones. Sin embargo, descubrirá un 98 FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. -

Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in the Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies

The Cine-Files, Issue 14 (spring 2019) Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies Ece Üçoluk Krane In this article I will consider insights emerging from the field of Animal Studies in relation to a selection of films in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (hereafter TCSM) franchise. By paying close attention to the construction of the animal subject and the human-animal relation in the TCSM franchise, I will argue that the original 1974 film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre II (1986) and the 2003 reboot The Texas Chain Saw Massacre all transgress the human-animal boundary in order to critique “carnism.”1 As such, these films exemplify “posthuman cannibalism,” which I define as a trope that transgresses the human-nonhuman boundary to undermine speciesism and anthropocentrism. In contrast, the most recent installment in the TCSM franchise Leatherface (2017) paradoxically disrupts the human-animal boundary only to re-establish it, thereby diverging from the earlier films’ critiques of carnism. For Communication scholar and animal advocate Carrie Packwood Freeman, the human/animal duality lying at the heart of speciesism is something humans have created in their own minds.2 That is, we humans typically do not consider ourselves animals, even though we may acknowledge evolution as a factual account of human development. Freeman proposes that we begin to transform this hegemonic mindset by creating language that would help humans rhetorically reconstruct themselves as animals. Specifically, she calls for the replacement of the term “human” with “humanimal” and the term “animal” with “nonhuman animal.”3 The advantage of Freeman’s terms is that instead of being mutually exclusive, they are mutually inclusive terms that foreground commonalities between humans and animals instead of differences. -

![Une Tragédie Gore / Scream 2 De Wes Craven]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7448/une-trag%C3%A9die-gore-scream-2-de-wes-craven-417448.webp)

Une Tragédie Gore / Scream 2 De Wes Craven]

Document generated on 09/29/2021 11:05 p.m. 24 images Une tragédie gore Scream 2 de Wes Craven Marcel Jean Number 91, Spring 1998 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/23647ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Jean, M. (1998). Review of [Une tragédie gore / Scream 2 de Wes Craven]. 24 images, (91), 52–52. Tous droits réservés © 24 images, 1998 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Scream 2 de wes crave n tation finale se déroule sur la scène). Craven poursuit enfin son travail sur la représenta tion à travers quelques scènes où il isole l'image du son (recours au téléphone, à la caméra vidéo, puis aux espaces insonorisés d'un studio d'enregistrement). De tout cet étalage, deux éléments ressortent. D'abord la fonction cathattique du cinéma d'horreur, qui est en quelque sorte mise de l'avant par le cinéaste qui se plaît à confronter le spectateur à sa propre Sarah Michelle Gellar. Un film annonçant la fin du gore. jouissance face à l'expérience de la peur. -

The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie

DOI: 10.24843/JH.2018.v22.i03.p30 ISSN: 2302-920X Jurnal Humanis, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Unud Vol 22.3 Agustus 2018: 771-780 The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie Ni Putu Ayu Mitha Hapsari1*, I Nyoman Tri Ediwan2, Ni Luh Nyoman Seri Malini3 [123]English Department - Faculty of Arts - Udayana University 1[[email protected]] 2[[email protected]] 3[[email protected]] *Corresponding Author Abstract The title of this paper is The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. This study focuses on categorization and function of the characters in the movie and conflicts in the main character (external and internal conflicts). The data of this study were taken from a movie entitled Doctor Strange. The data were collected through documentation method. In analyzing the data, the study used qualitative method. The categorization and function were analyzed based on the theory proposed by Wellek and Warren (1955:227), supported by the theory of literature proposed by Kathleen Morner (1991:31). The conflict was analyzed based on the theory of literature proposed by Kenney (1966:5). The findings show that the categorization and function of the characters in the movie are as follows: Stephen Strange (dynamic protagonist character), Kaecilius (static antagonist character). Secondary characters are The Ancient One (static protagonist character), Mordo (static protagonist character) and Christine (dynamic protagonist character). The supporting character is Wong (static protagonist character). Then there are two types of conflicts found in this movie, internal and external conflicts. Keywords: Character, Conflict, Doctor Strange. Abstrak Judul penelitian ini adalah The Characters and Conflicts in Marvel Studios “Doctor Strange” Movie. -

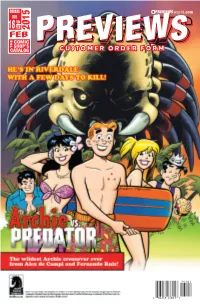

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Unmasking the Devil: Comfort and Closure in Horror Film Special Features

Unmasking the Devil: Comfort and Closure in Horror Film Special Features ZACHARY SHELDON While a viewer or critic may choose to concentrate solely on a film’s narrative as representative of what a film says, some scholars note that the inclusion of the supplementary features that often accompany the home release of a film destabilize conceptions of the text of a film through introducing new information and elements that can impact a film’s reception and interpretation (Owczarski). Though some special features act as mere advertising for a film’s ancillary products or for other film’s or merchandise, most of these supplements provide at least some form of behind-the-scenes look into the production of the film. Craig Hight recognizes the prominent “Making of Documentary” (MOD) subgenre of special feature as being especially poised to “serve as a site for explorations of the full diversity of institutional, social, aesthetic, political, and economic factors that shape the development of cinema as a medium and an art form” (6). Additionally, special features provide the average viewer access to the magic of cinema and the Hollywood elite. The gossip or anecdotes shared in interviews and documentaries in special features provide viewers with an “insider identity,” that seemingly involves them in their favorite films beyond the level of mere spectator (Klinger 68). This phenomenon is particularly interesting in relation to horror films, the success of which is often predicated on a sense of mystery or the unknown pervading the narrative so as to draw out visceral affective responses from the audience. The notion of the special feature, which unpacks and reveals the inner workings of the film set and even the film’s plot, seems contradictory to the enjoyment of what the horror film sets out to do.