(GNU) Emacs 24 Matthew Chan, Themattchan.Com, Last Updated November 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PC Basics Bronze Level

PC Basics Bronze Level Keyboard Call us on 03333 444019 Learning Guide Getting Started: Using the Keyboard The Keyboard is, along with the mouse, vital to controlling your computer. Keyboards work by translating your keystrokes into a signal that a computer can understand. Keyboards usually have a standard layout but there are some “special keys” and “shortcuts” which are helpful to know about: Light sensors (for Tab Key Function Keys Delete Number Lock and Caps Lock) Escape Caps Lock Backspace Space Bar Number Keys Shift Enter Control Alt Arrow Keys Menu Key Windows Key Tip : The keyboard shown above is the FULL version that would come as a separate piece of equipment when you have a DESKTOP computer. The keyboard that is built-in on LAPTOPS is sometimes a smaller version of the one above. Please see over for a full explanation of all the above keys and buttons… Learning Guide Keyboard Commands Tab: Tab is used to advance the cursor to the next “tab spot”, which could be in a form (on the Internet) or in a letter (word processor) Caps Lock: Locks the keyboard so that anything you type is in CAPITAL LETTERS. Usually the computer shows some kind of warning that you have pressed this key e.g. a light on the keyboard Shift: Holding down the Shift key (usually denoted with a ↑on the key) has a number of uses, both to type capital letters and to access the symbols on the upper part of a key, e.g. the £ sign above the number 3. There are Shift keys on both sides of the keyboard. -

JAWS Keystrokes

JAWS Keystrokes The keystrokes listed here are in tables and are grouped by headings. Major divisions are level two headings. Use the JAWS List of Headings (INSERT+F6) or the navigation quick key, H, to move quickly to the section of your choice. You can also use the navigation quick key, T, to move from one table to the next. Use the SHIFT key in combination with most navigation quick keys to move backwards. New JAWS Keystrokes Layered Keystrokes Layered keystrokes are keystrokes that require you to first press and release INSERT+SPACEBAR, and then press a different key to perform a function in JAWS. Layered keystrokes are easy to use and remember, and they do not interfere with native keystrokes within applications. Once you enter a layer, press the QUESTION MARK key to get a list of available keyboard commands within that layer. Description Command Helpful keystrokes within QUESTION MARK - ? each layer Text Analyzer INSERT+SPACEBAR, A View text on clipboard INSERT+SPACEBAR, C Show recent speech history INSERT+SPACEBAR, H INSERT+SPACEBAR, Clear recent speech history SHIFT+H Keyboard Lock on and off INSERT+SPACEBAR, L INSERT+SPACEBAR, M Select from marked place in (Mark Place first with Word (Microsoft Word only) CTRL+WINDOWS Key+K) Convenient OCR INSERT+SPACEBAR, O Research It INSERT+SPACEBAR, R Description Command Toggle Speech On or Off INSERT+SPACEBAR, S Table Layer INSERT+SPACEBAR, T Customize Web page with INSERT+SPACEBAR, X Flexible Web Windows Live Messages 1 through 5 numbers row JAWS Tandem Session Keystrokes Description Command Toggle Target and Controller Desktop Tandem Session INSERT+ALT+TAB (Controller User) Terminate JAWS Tandem Session (Controller or Target INSERT+ALT+T User) Pause Video (Controller INSERT+CTRL+SHIFT+V User) Web Pages and HTML Navigation quick keys make it faster and easier to move around on a Web page and anywhere else the Virtual Cursor is active. -

Magic Flip Chart

MAGic Most Used General Commands Description MAGic Keyboard Combination Keyboard Launch MAGic: Starts MAGic or closes MAGic if it is CTRL+ALT+M (only starts MAGic) running. Toolbar: Displays or hides the MAGic toolbar (user CAPS LOCK+U interface). CAPS LOCK+APPLICATION KEY MAGic Context Menu: Opens the MAGic context or menu for quick changes to MAGic settings. CAPS LOCK+RIGHT MOUSE BUTTON CLICK Decrease Rate: Decreases the MAGic speech rate. Increase Rate: Increases the MAGic speech rate. 440557-001 Rev. F www.FreedomScientific.com 800-444-4443 MAGic Magnification Commands Description MAGic Keyboard Combination Keyboard Visual Enhancements: Toggles all visual enhancements including magnification, mouse CAPS LOCK+DELETE enhancements, color enhancements, focus enhancements, and cursor enhancements. Mag Level Toggle: Switches between the current CAPS LOCK+SHIFT+DELETE magnification level and 1x magnification. All visual or enhancements will remain active. CAPS LOCK+MOUSE WHEEL CLICK CAPS LOCK+NUM PAD PLUS or Increase Magnification CAPS LOCK+MOUSE WHEEL UP or CTRL+EQUALS CAPS LOCK+NUM PAD PLUS or Decrease Magnification CAPS LOCK+MOUSE WHEEL UP or CTRL+DASH www.FreedomScientific.com 800-444-4443 MAGic Visual Enhancement Toggles Description MAGic Keyboard Combination Keyboard Mouse Enhancements: When enabled, mouse enhancements make the mouse pointer easier to track CAPS LOCK+F4 and maneuver on the screen. Cursor Enhancements: When enabled, this makes the cursor easier to locate and follow when writing or CAPS LOCK+F8 editing text. Color Enhancements: Color enhancements can be adjusted to meet individual needs for handling glare CAPS LOCK+F12 and contrast. Focus Enhancement: Displays a rectangular border that identifies and tracks the control that currently has CAPS LOCK+F the focus. -

Hot Key Reference Guide

Hot Key Reference Guide Hot Keys for Desktops, Laptops & Touch Screens This information is available in alternative formats from www.YourDolphin.com Introduction 1 This booklet lists the most useful hot keys to control the three editions of Dolphin SuperNova: Magnifier Magnifier & Speech Magnifier & Screen Reader A list of all the hot keys for your SuperNova software can be found in the user manual. To open the manual, press F1 or click the “Help” button on the SuperNova Control Panel. To get context help and a list of available hot keys while using particular applications press CAPS LOCK + F1 from within your application. Most users prefer the default Dolphin hot key set as the most popular Speak commands can be operated by pressing a single key. When a hot key includes “NUMPAD”, this means that the key is situated on the numeric keypad, a block of keys usually on the right end of your keyboard. On a laptop the Numpad keys are usually available by holding down the FN key. Where the Numpad is unavailable or difficult to use, we recommend using the Laptop Keyboard layout. Throughout this document, Laptop hot keys that differ from the desktop are shown inside square brackets. Choosing the Keyboard Layout and Hot Key Set While SuperNova is running, open the SuperNova Control Panel by holding LEFT CONTROL and pressing SPACEBAR. Then press ALT + G to open the "General" menu, press K to open the "Keyboard and hot keys" dialogue where you can choose: keyboard layout, keyboard language and preferred hot key set. Press OK to save any changes and close the dialogue. -

Corrosion Mechanisms of Mild Steel in Weak Acids

Corrosion Mechanisms of Mild Steel in Weak Acids A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Russ College of Engineering and Technology of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Thu N.B. Tran August 2014 © 2014 Thu N.B. Tran. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Corrosion Mechanisms of Mild Steel in Weak Acids by THU N.B. TRAN has been approved for the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and the Russ College of Engineering and Technology by Srdjan Nesic Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Dennis Irwin Dean, Russ College of Engineering and Technology 3 ABSTRACT TRAN, THU N.B., Ph.D., August 2014, Chemical Engineering Corrosion Mechanisms of Mild Steel in Weak Acids Director of Dissertation: Srdjan Nesic The corrosion of mild steel in the presence of weak acids is a challenge for the oil and gas industry. Weak acids, such as carbonic acid (in CO2 corrosion) and acetic acid, are reported to accelerate the cathodic reaction, but there is still little agreement as to their role in corrosion mechanisms. Although assumed in many studies, there is no proof that direct reduction of these weak acids occurs and needs to be taken into account. Therefore, the intent of this research is to determine whether these weak acids mainly provide hydrogen ions via their dissociation, with resultant hydrogen ions being directly reduced at the steel surface, or if the direct reduction of weak acids is also important. Electrochemical techniques including linear polarization resistance (LPR), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and polarization sweeps were used to investigate the corrosion mechanisms. -

Development of Medical Equipment to Make Colonoscopy Procedures Safer For

Development of Medical Equipment to make Colonoscopy Procedures Safer for Physicians: Control Head Holder and Splatter Shield A thesis presented to the faculty of the Russ College of Engineering and Technology of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Rajesh Ravindra Shanbhag December 2014 © 2014 Rajesh Ravindra Shanbhag. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Development of Medical Equipment to make Colonoscopy Procedures Safer for Physicians: Control Head Holder and Splatter Shield by RAJESH RAVINDRA SHANBHAG has been approved for the Department of Mechanical Engineering and the Russ College of Engineering and Technology by JungHun Choi Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering Dennis Irwin Dean, Russ College of Engineering and Technology 3 ABSTRACT SHANBHAG, RAJESH RAVINDRA, M.S., December 2014, Mechanical Engineering Development of Medical Equipment to make Colonoscopy Procedures Safer for Physicians: Control Head Holder and Splatter Shield Director ofThesis: JungHun Choi The physicians performing colonoscopy are at risk due to the occupational overuse injuries and exposure to infectious splatters from the patient’s anus. The objective of this thesis is to develop medical equipment to make the colonoscopy procedure safer and more comfortable for performing physicians. To understand the problem well, the colonoscopy procedure was directly observed. Additionally, physicians were questioned to better comprehend safety issues associated with the procedure. Subsequently, two devices were developed in an attempt to make the procedure safer for the physicians[1]. The Control Head Holder (CHH) holds the control head of the colonoscopy equipment, which provides the physician with less fatigue during the procedure. A splatter shield was also developed to mitigate the physician’s exposure to bodily fluids. -

Learning GNU Emacs Other Resources from O’Reilly

Learning GNU Emacs Other Resources from O’Reilly Related titles Unix in a Nutshell sed and awk Learning the vi Editor Essential CVS GNU Emacs Pocket Reference Version Control with Subversion oreilly.com oreilly.com is more than a complete catalog of O’Reilly books. You’ll also find links to news, events, articles, weblogs, sample chapters, and code examples. oreillynet.com is the essential portal for developers interested in open and emerging technologies, including new platforms, pro- gramming languages, and operating systems. Conferences O’Reilly brings diverse innovators together to nurture the ideas that spark revolutionary industries. We specialize in document- ing the latest tools and systems, translating the innovator’s knowledge into useful skills for those in the trenches. Visit con- ferences.oreilly.com for our upcoming events. Safari Bookshelf (safari.oreilly.com) is the premier online refer- ence library for programmers and IT professionals. Conduct searches across more than 1,000 books. Subscribers can zero in on answers to time-critical questions in a matter of seconds. Read the books on your Bookshelf from cover to cover or sim- ply flip to the page you need. Try it today with a free trial. THIRD EDITION Learning GNU Emacs Debra Cameron, James Elliott, Marc Loy, Eric Raymond, and Bill Rosenblatt Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Paris • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Learning GNU Emacs, Third Edition by Debra Cameron, James Elliott, Marc Loy, Eric Raymond, and Bill Rosenblatt Copyright © 2005 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. -

The Affirmative Driverless PC/5250 Keyboard Has Been Optimized For

The Affirmative 122-Key Driverless PC/5250 keyboard has been optimized for IBM Client Access 5250 and should be compatible with other 5250 emulation software packages which include a keyboard mapping utility. The PC/5250 keyboard uses the Microsoft standard 101/102-key keyboard driver and does not require any additional keyboard drivers. Figure 1 shows the layout of this keyboard with the keycap nomenclature. F13 F14 F15 F16 F17 F18 F19 F20 F21 F22 F23 F24 F1 F2 F3 F4 F5 F6 F7 F8 F9 F10 F11 F12 Figure 1. 122-Key Driverless PC/5250 Keyboard Layout PC functions are in black. 5250 unique functions are in blue SysRq | ! @ # $ % ^ ¬ & * ( ) _ + Dup NumLk Esc ~ PgUp End Insert ScrLk / * Attn ¢ ` 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = RollDn Zoom Jump Cl Print Pause { } 7 89 - TAB QWE R TYUI OP Delete PgDn Scrn Clear [ ] Enter RollUp Home PgUp Field - SysRq Break Rule : " ¦ 456 Print Help Caps Lock A S D FGHJK L Field+ ; ' \ + Field Exit ? , . ? 2 Recrd Play ShiftZ X C V B N M Shift 1 3 , . / Home End . PgDn Enter Win Win Ctrl Alt Alt Ctrl 0 . Field Start Apps Reset Enter Ins Del Exit Quit To use the Driverless PC/5250 keyboard, the user must ensure that the 5250 functions are mapped properly by the emulation software program being used. Most of the key mappings are standard (between emulation packages) and will require no changes to the system’s configuration and set-up. However, some changes will probably be required using the emulation software’s keyboard mapping utility to enable a few specific functions. -

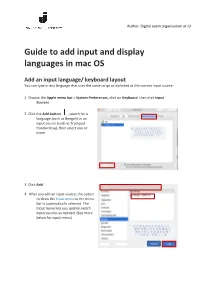

Guide to Add Input and Display Languages in Mac OS

Author: Digital exam organisation at JU Guide to add input and display languages in mac OS Add an input language/ keyboard layout You can type in any language that uses the same script or alphabet as the current input source. 1 Choose the Apple menu bar > System Preferences, click on Keyboard, then click Input Sources 2 Click the Add button , search for a language (such as Bengali) or an input source (such as Trackpad Handwriting), then select one or more 3 Click Add Choose among languages or choose an input source 4 After you add an input source, the option to show the Input menu in the menu bar is automatically selected. The Input menu lets you quickly switch input sources as needed. (See more below for input menu) Cancel Add Author: Digital exam organisation at JU Switch between input sources Input menu To switch between input sources, do any of the following: ▪ Use the Input menu: Click the Input menu in the menu bar, then choose an input source. If an input source is dimmed, the current app doesn’t support it ▪ Use the Caps Lock key: Press the Caps Lock key to switch between a non-Latin input source (such as Chinese or Korean) and a Latin input source (such as French or English). To use this method, you must select the “Use Caps Lock to switch to and from” option in the Input Sources pane. Choose Apple menu > System Preferences, click Keyboard, then click Input Sources ▪ Use keyboard shortcuts: Press Option-Control-Space bar to select the next input source in the Input menu, or Control-Space bar to select the previous input source When you add input sources, those languages are automatically added to the list of preferred languages in Language & Region preferences; you can set your Mac to use one of those languages. -

Title Keyboard : All Special Keys : Enter, Del, Shift, Backspace ,Tab … Contributors Dhanya.P Std II Reviewers Submission Approval Date Date Ref No

Title Keyboard : All special keys : Enter, Del, Shift, Backspace ,Tab ¼ Contributors Dhanya.P Std II Reviewers Submission Approval Date Date Ref No: This topic describes the special keys on the keyboard of a computer Brief Description and their functionalities . Goal To familiarize the special keys on the keyboard of a computer. Pre-requisites Familiarity with computer. Learning Concepts that special keys on a keyboard has special functionalities. Outcome One Period Duration http://www.ckls.org/~crippel/computerlab/tutorials/keyboard/ References http://computer.howstuffworks.com/ Page Nos: 2,3,4,5,6 Detailed Description Page No: 7 Lesson Plan Page No: 7 Worksheet Page No: 8 Evaluation Page No: 8 Other Notes Detailed Description A computer keyboard is a peripheral , partially modeled after the typewriter keyboard. Keyboards are designed for the input of text and characters. Special Keys Function Keys Cursor Control Keys Esc Key Control Key Shift Key Enter Key Tab Key Insert Key Delete Key ScrollLock Key NumLock Key CapsLock Key Pasue/Break Key PrtScr Key Function Keys F1 through F12 are the function keys. They have special purposes. The following are mainly the purpose of the function keys. But it may vary according to the software currently running. # F1 - Help # F2 - Renames selected file # F3 - Opens the file search box # F4 - Opens the address bar in Windows Explorer # F5 - Refreshes the screen in Windows Explorer # F6 - Navigates between different sections of a Windows Explorer window # F8 - Opens the start-up menu when booting Windows # F11 - Opens full screen mode in Explorer Function Keys F1 through F12 are the function keys. -

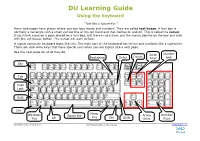

DU Learning Guide Using the Keyboard

DU Learning Guide Using the keyboard “Just like a typewriter.” Many web pages have places where you can type words and numbers. They are called text boxes. A text box is normally a rectangle with a small vertical line at the left hand end that flashes on and off. This is called the cursor. If you think a box on a page should be a text box, but there is no cursor, put the mouse pointer on the box and click with the left mouse button. The cursor will start to flash. A typical computer keyboard looks like this. The main part of the keyboard has letters and numbers like a typewriter. There are also some keys that have special uses when you are typing into a web page. See the next page for what they do. Scroll Number Delete Backspace Enter Keys Lock Esc Tab Caps Lock Shift Ctrl Menu Windows Space Bar Arrow Number Key Key Alt Ctrl Shift Keys Keys © Digital Unite Limited 2010 LG003_Using_the_keyboard.doc digitalunite.com DU Learning Guide: Using the keyboard Esc (escape) clears any text that you have typed in a text box. Tab moves the cursor to the next box in a form. Caps Lock locks the keyboard so that it types capitals. There’s a light on the top of the keyboard to show whether the Caps Lock is on. It has a letter A below it. NB Caps Lock does not give you the upper number key symbols. Hold down the Shift key to type capital letters and the symbols on the upper part of a key, e.g. -

Kirilmath — Cyrillic and Maths Kirilmath Version 1.10

kirilmath | Cyrillic and maths kirilmath version 1.10 Georgi Boshnakov Copyright c 2006-2012 Georgi Boshnakov Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this manual provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this manual under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1 Introduction This documentation is a draft. A common and extremely irritating mistake when writing mathematical texts in Bul- garian (and other Cyrillic based languages) is to forget to switch the character encoding when changing from maths (which uses Latin alphabet) to text (Cyrillic alphabet) and vice versa. In Emacs the alternative encoding is specified by a default input method which is turned on (for text) or off (for mathematics or a Latin based text). We provide commands that almost eliminate the need to manually turn the default encoding on and off when editing text. This package is intended to be used mainly in TEX modes in conjunction with AUCTeX. Some of the commands are meaningful in ordinary text modes, too. These features are best used in connection with AucTeX. Chapter 2: Installation 2 2 Installation This package can be installed through the packaging system distributed with Emacs 24 and available as add-on for older versions of Emacs. The package currently resides in my package archive at http://www.maths.manchester. ac.uk/~gb/emacs/packages/.