The Law of Contracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divorce Retainer Agreement

RETAINER AGREEMENT FOR_________________________________________________________________ BETWEEN FIRM NAME:__________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: ___________________________________________________________ CITY/STATE___________________________________________________________ TEL. NO.:_____________________________________________________________ AND CLIENT: _____________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: ___________________________________________________________ CITY/STATE: __________________________________________________________ TEL. NO.: ____________________________________________________________ This law firm will represent you with respect to legal problems concerning your marriage. We have discussed this firm’s representation of you. We have fully explained to you all services of our firm and your duties to our firm. LAWYER’S DUTIES 1. The primary duty of this firm will be to represent you in your matrimonial dispute. This firm will make all necessary preparations and, with your permission, aid you in retaining all necessary experts to resolve some or all of the following issues: (a) Custody (b) Visitation (c) Alimony (d) Child Support (e) Division of property (f) Allocation of counsel fees and costs (g) Other ____________________________________________ 2. This firm’s duties end upon entry of a final court order. This agreement will apply only to work to be performed by this firm at the trial level. If you wish to appeal the result after completion of the trial, we have to come to a new agreement. NO GUARANTEE 3. Judges are granted great discretion in matrimonial matters, so this firm cannot guarantee the results. REPRESENTATION BY THE FIRM 4. Any lawyer in the firm may be involved in your case. A partner will be in charge of managing your case. You may communicate with the partner in charge or with any of our other lawyers who may be handling your case. WITHDRAWAL BY LAWYER 5. (a) If you do not pay our bills on time, we shall be free to ask the court for permission to withdraw as your lawyer. -

New York Supreme Court APPELLATE DIVISION—FIRST DEPARTMENT

To Be Argued By: MARC E. ISSERLES New York County Clerk’s Index No. 113781/09 New York Supreme Court APPELLATE DIVISION—FIRST DEPARTMENT dSCAROLA ELLIS LLP, Plaintiff-Respondent, —against— ELAN PADEH, Defendant-Appellant. REPLY BRIEF FOR DEFENDANT-APPELLANT ALEXANDRA A.E. SHAPIRO MARC E. ISSERLES JAMES DARROW SHAPIRO, ARATO & ISSERLES LLP 500 Fifth Avenue, 40th Floor New York, New York 10110 (212) 257-4880 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant REPRODUCED ON RECYCLED PAPER TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................... ii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................. 4 I. THE UNJUST ENRICHMENT CAUSE OF ACTION IS LEGALLY DEFICIENT AND SHOULD NOT HAVE GONE TO THE JURY ... 4 A. An Express Agreement Bars An Unjust Enrichment Claim Covering The Same Subject Matter ............................................... 4 B. Scarola’s “Correctly Calculated” Damages Theory Is Indefensible ..................................................................................... 9 C. Scarola’s Remaining Arguments Are Without Merit ................... 15 1. Padeh Specifically Challenged The Quasi-Contract Claims Below ............................................................................................ 15 2. Scarola Cannot Avoid A Valid Settlement By Calling It -

In the Supreme Court of Georgia Decided

In the Supreme Court of Georgia Decided: September 8, 2020 S19G1026. INNOVATIVE IMAGES, LLC v. JAMES DARREN SUMMERVILLE, et al. NAHMIAS, Presiding Justice. Innovative Images, LLC (“Innovative”) sued its former attorney James Darren Summerville, Summerville Moore, P.C., and The Summerville Firm, LLC (collectively, the “Summerville Defendants”) for legal malpractice. In response, the Summerville Defendants filed a motion to dismiss the suit and to compel arbitration in accordance with the parties’ engagement agreement, which included a clause mandating arbitration for any dispute arising under the agreement. The trial court denied the motion, ruling that the arbitration clause was “unconscionable” and thus unenforceable because it had been entered into in violation of Rule 1.4 (b) of the Georgia Rules of Professional Conduct (“GRPC”) for attorneys found in Georgia Bar Rule 4-102 (d). In Division 1 of its opinion in Summerville v. Innovative Images, LLC, 349 Ga. App. 592 (826 SE2d 391) (2019), the Court of Appeals reversed that ruling, holding that the arbitration clause was not void as against public policy or unconscionable. See id. at 597-598. We granted Innovative’s petition for certiorari to review the Court of Appeals’s holding on this issue. As explained below, we conclude that regardless of whether Summerville violated GRPC Rule 1.4 (b) by entering into the mandatory arbitration clause in the engagement agreement without first apprising Innovative of the advantages and disadvantages of arbitration – an issue which we need not address – the clause is not void as against public policy because Innovative does not argue and no court has held that such an arbitration clause may never lawfully be included in an attorney-client contract. -

Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition Mark Aaronson UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected]

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 2019 Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition Mark Aaronson UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Mark Aaronson, Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition, 27 J. Affordable Housing 549 (2019). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/1718 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition Mark Neal Aaronson I. In tro d uctio n ............................................................................................. 54 9 II. The Political and Professional Context ................................................ 552 III. Workin g in C oalition .............................................................................. 559 A . The H astings C ED C linic ................................................................ 559 B . W h o Is th e C lien t? ......................................... ................................... 560 C. M obilization and Collaboration .................................................... 562 D. The Development Agreement's Terms ........................................ -

Retainer Agreement This ATTORNEY

Retainer Agreement This ATTORNEY-CLIENT FEE CONTRACT ("Contract") is entered into by and between ("Client/Corporation") and JUN WANG & ASSOCIATES, P.C. ("Attorney"). 1. CONDITIONS. This Contract will not take effect, and Attorney will have no obligation to provide legal services, until Client returns a signed copy of this Contract and pays the deposit called for under paragraph 5. 2. SCOPE AND DUTIES. Client hires Attorney to provide legal services in connection with PERM Labor Certification Process for (Beneficiary) sponsored by (Employer). Attorney shall provide those legal services reasonably required to represent Client and shall take reasonable steps to keep Client informed of progress and to respond to Client's inquiries. Client shall be truthful with Attorney, cooperate with Attorney, keep Attorney informed of developments, abide by this Contract, pay Attorney's bills on time and keep Attorney advised of Client's address, telephone number and whereabouts. Attorney’s services in this matter will end, unless otherwise agreed upon in writing signed by Attorney, when there is a final agreement, settlement, decision or judgment by the court. 3. GUARANTEE OF PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCE. Attorney agrees to use due diligence in furthering Client’s best interests under the laws. Attorney is liable to Client for Attorney’s negligence or incompetence. However, Attorney makes on guarantee of the outcome of this representation. 4. LEGAL FEES AND EXPENSES. In consideration of the professional services rendered and to be rendered, the client agrees to pay the fee $4,000 as legal fee, plus costs and expenses. Client agrees to pay $50.00 administrative cost for bounced or stopped payment checks per transaction. -

CPY Document

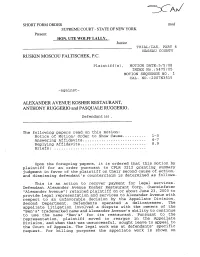

....... SHORT FORM ORDER mod SUPREME COURT - ST ATE OF NEW YORK Present: HON. UTE WOLFF LALLY. Justice TRIAL/lAS, PART NASSAU COUNTY RUSKIN MOSCOU FALTISCHEK, P. Plaintiff (s) , MOTION DATE: 5/5/08 INDEX No. : 5475/05 MOTION SEQUENCE No. CAL. NO. : 2007N3515 against- ALEXANDER A VENUE KOSHER RESTAURANT ANTHONY RUGGERIO and PASQUALE RUGGERIO, Defendant (s) . The following papers read on this motion: Notice of Motion/ Order to Show Cause. Answering Affidavits. Replying Affidavits. Briefs: Upon the foregoing papers, it is ordered that this motion by plaintiff for an order pursuant to CPLR 3212 granting sumary judgment in favor of the plaintiff on their second cause of action, and dismissing defendant I s counterclaim is determined as follows. This is an action to recover payment for legal services. Defendant Alexander Avenue Kosher Restaurant Corp. (hereinfater Alexander Avenue ) retained plaintiff on or about June 23, 2003 to provide legal representation and services to Alexander Avenue with respect to an unfavorable decision by the Appellate Division, Second Department. Defendants operated a delicatessen. The appellate litigation involved a dispute with the owners of the Ben " trademarked name and Alexander Avenue' s abili ty to continue to use the name " Ben for its restaurant. Pursuant to the representation, plaintiff moved to reargue in the Appellate Division, and when that was unsuccessful, sought leave to appeal the Court of Appeals. The legal work was at defendants ' specific request. For billing purposes the appellate work is shown on Ruskin v Alexander Avenue - 2 - Index No. 5475/05 plaintiff' s invoices, and referred to hereinafter as " Matter No. -

Legal Malpractice 2019 Professional Liability Claims, Litigation Strategies, and Attorney Disciplinary Procedures

Legal Malpractice 2019 Professional Liability Claims, Litigation Strategies, and Attorney Disciplinary Procedures TUESDAY, MARCH 19 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 20 Albany Long Island MONDAY, MARCH 25 THURSDAY, MARCH 28 New York City Rochester TUESDAY, APRIL 16 Westchester Program time is from 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. at all participating locations. 4.0 MCLE Credits: 3.0 in Ethics, 1.0 Law Practice Management Sponsored by the Committee on Continuing Legal Education and the Law Practice Management Committee of the New York State Bar Association This program is offered for educational purposes. The views and opinions of the faculty expressed during this program are those of the presenters and authors of the materials. Further, the statements made by the faculty during this program do not constitute legal advice. Copyright © 2019 All Rights Reserved New York State Bar Association Program Description Lawsuits against lawyers arising from errors and/or omissions in the performance of legal services continue to rise. It is an essential part of a law firm’s business practice to evaluate its legal risk and malpractice insurance needs. This program is designed to educate attorneys on how to prosecute and/or defend a legal malpractice action. In addition, this program will educate attorneys about their legal malpractice exposures, what they should do in the event that a lawsuit or a grievance complaint is filed against them, and what they should do when situations arise that indicate that a legal malpractice claim is likely. Both solo practitioners and members of larger firms would benefit from knowing how to assess professional liability risk and manage legal malpractice litigation. -

General Retainer Agreement

GARDINER MILLER ARNOLD LLP GENERAL RETAINER AGREEMENT We (the “Client” or “Clients” if more than one) hereby retain Gardiner Miller Arnold LLP (“GMA”) as our lawyers for legal advice and representation on the following “Retainer” (please fill in the services you would like): Subject to our written instructions, we request that GMA take any actions that GMA deems necessary and appropriate to assist us on completing the Retainer. Legal Fees and Disbursements: In exchange for completing the Retainer, the Client agrees to pay GMA legal fees calculated based on billable hours required to complete the matter multiplied by the applicable hourly rates in the attached Schedule of Hourly Rates. In addition to legal fees, the Client will pay any disbursements plus applicable harmonized sales tax. Invoicing and Unpaid Accounts: GMA will invoice the Client for legal fees, disbursements and applicable taxes. In the event that accounts remain unpaid for more than 30 days, GMA may (in its discretion) charge the Client interest at rates permitted under the Solicitor’s Act (Ontario). Prepaid Fees: GMA may request that the Client provide an initial financial retainer as a prepayment of legal fees, disbursements and taxes. The prepayment may be provided by cheque, wire transfer, bank draft or other payment method acceptable to GMA. However, GMA will not accept cash in excess of $1,000.00. The Client authorizes and directs GMA to hold the prepayment cheque amount in its non-interest bearing general trust account. Upon written request from GMA, the Client agrees to replenish this financial retainer within 3 business days. -

Retainer Agreement

11777 SAN VICENTE BLVD., SUITE 702 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90049 SELARZ LAW CORP. TELEPHONE: 310.651.8685 FAX: 310.651.8681 Attorney-Client Contingency Fee Retainer Agreement This ATTORNEY-CLIENT CONTINGENCY FEE CONTRACT (the “Agreement”) is the written fee contract that California law requires lawyers to have with their clients. It is between SELARZ LAW CORP. (“Attorney”) and [CLIENT’S NAME] (“Client”). 1) CONDITIONS. This Agreement will not take effect, and Attorney will have no obligation to provide legal services, until Client returns a signed copy of this Agreement. 2) SCOPE OF SERVICES. Client is hiring Attorney to represent Client in the matter of Client’s claims arising out of Client’s [Date], [Type of Accident]. Attorney will provide those legal services reasonably required to represent Client in these claims and will take reasonable steps to inform Client of progress and to respond to Client’s inquiries. Attorney will represent Client in any court action until a settlement or judgment, by motion, arbitration or trial, is reached, and in connection with any appropriate post-trial motions. After judgment, Attorney will not represent Client on any appeal, or in any proceedings designed to execute on the judgment, unless Client and Attorney agree that Attorney will provide such services and also agree upon additional fees, if any, to be paid to attorney for such services. 3) CLIENT’S DUTIES. Client agrees to be truthful with Attorney, to cooperate, to keep Attorney informed of any developments, to abide by this Agreement, to pay bills for costs (if any) on time, and to keep Attorney informed of Client’s address, telephone number and whereabouts. -

Opening Brief

To Be Argued By: MARC E. ISSERLES New York County Clerk’s Index No. 113781/09 New York Supreme Court APPELLATE DIVISION—FIRST DEPARTMENT dSCAROLA ELLIS LLP, Plaintiff-Respondent, —against— ELAN PADEH, Defendant-Appellant. BRIEF FOR DEFENDANT-APPELLANT ALEXANDRA A.E. SHAPIRO MARC E. ISSERLES JAMES DARROW SHAPIRO, ARATO & ISSERLES LLP 500 Fifth Avenue, 40th Floor New York, New York 10110 (212) 257-4880 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant REPRODUCED ON RECYCLED PAPER TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................... iii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ............................................................................... 1 QUESTIONS PRESENTED ...................................................................................... 4 STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................ 4 A. Elan Padeh Enters Into A Contingency-Fee Agreement With George Zelma And Sues Corcoran ........................................................................................... 4 B. Corcoran Brings Related Counterclaims Against Padeh And Virtually Identical Third-Party Claims Against Padeh’s Company In A Consolidated Action ............................................................................................................... 6 C. The Scarola Firm Takes Over Padeh’s Case Pursuant To A Co-Representation Agreement With Zelma .................................................... -

Attorney-Client Representation Agreement

ATTORNEY-CLIENT REPRESENTATION AGREEMENT This agreement is made between The Law Offices of Jeffrey N. Golant, P.A. and ____________________ . Throughout the remainder of this document, The Law Offices of Jeffrey N. Golant, P.A. will be referred to as “Attorney” and ________________________ will be referred to either singularly or collectively as “Client.” This agreement is a contract, and shall describe the services that Attorney will provide to Client, the compensation that Attorney will receive, and each parties’ obligations relating to the performance of this contract. This agreement is specifically designed for clients who have claims or potential claims arising from the improper servicing of their mortgage loan. SECTION I. - EFFECTIVE DATE This contract shall take effect upon its execution by both parties. SECTION II. – SCOPE OF REPRESENTATION The services that Attorney will provide to Client shall take place in three different stages, and each stage shall involve somewhat different compensation. However, the matter may conclude before the second or third stage is reached. Stage One – Free Consultation In the first stage, Attorney will assist Client in determining whether Client’s mortgage loan account has been handled improperly by Client’s mortgage servicer. During this stage, Attorney will evaluate potential legal issues affecting Client’s mortgage loan account, but will not render any substantive services in connection with either the prosecution or defense of any litigation. It may take some time to complete this stage. In most cases, as part of an “extended free consultation” Attorney will send formal correspondence on Client’s behalf to a mortgage servicer seeking information or notifying the mortgage servicer of an error. -

The Law of Lawyers' Contracts Is Different

Fordham Law Review Volume 67 Issue 2 Article 8 1998 The Law of Lawyers' Contracts Is Different Joseph M. Perillo Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph M. Perillo, The Law of Lawyers' Contracts Is Different, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 443 (1998). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Law of Lawyers' Contracts Is Different Cover Page Footnote Distinguished Professor, Fordham University School of Law; A.B. Cornell, 1953; J.D. Cornell, 1955. I wish to express my thanks for the valuable research assistance of Meredith Grauer, David Pieterse, and Rob Gresham. Professors Mary Daly, Bruce Green, and Russell Pearce made helpful comments on an earlier draft for which I am most appreciative. I am grateful to Fordham University for supporting this article with a summer grant. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss2/8 THE LAW OF LAWYERS' CONTRACTS IS DIFFERENT Joseph M. Perillo* The greatest Trust, betweene Man and Man, is the Trust of Giving CounselL For in other Confidences, Men commit the parts of life; Their Lands, their Goods, their Children, their Credit, some partic- ular Affaire: But to such, as they make their Counsellours, they commit the whole: By how much the more, they are obliged to all Faith and integrity.** CONTENTS I.