Social Sciences and Public Policy, Vol. 11, Number 1, Pp. 37-52

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Byjibrin Ibrahim

Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa Jibrin Ibrahim Monograph Series The CODESRIA Monograph Series is published to stimulate debate, comments, and further research on the subjects covered. The Series will serve as a forum for works based on the findings of original research, which however are too long for academic journals but not long enough to be published as books, and which deserve to be accessible to the research community in Africa and elsewhere. Such works may be case studies, theoretical debates or both, but they incorporate significant findings, analyses, and critical evaluations of the current literature on the subjects in question. Author Jibrin Ibrahim directs the International Human Rights Law Group in Nigeria, which he joined from Ahmadu Bello University where he was Associate Professor of Political Science. His research interests are democratisation and the politics of transition, comparative federalism, religious and ethnic identities, and the crisis in social provisioning in Africa. He has edited and co-edited a number of books, among which are Federalism and Decentralisation in Africa (University of Fribourg, 1999), Expanding Democratic Space in Nigeria (CODESRIA, 1997) and Democratisation Processes in Africa, (CODESRIA, 1995). Democratic Transition in Anglophone West Africa © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa 2003, Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop Angle Canal IV, BP. 3304, Dakar, Senegal. Web Site: http://www.codesria.org CODESRIA gratefully -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

Accredited Observer Groups/Organisations for the 2011 April General Elections

ACCREDITED OBSERVER GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS FOR THE 2011 APRIL GENERAL ELECTIONS Further to the submission of application by Observer groups to INEC (EMOC 01 Forms) for Election Observation ahead of the April 2011 General Elections; the Commission has shortlisted and approved 291 Domestic Observer Groups/Organizations to observe the forthcoming General Elections. All successful accredited Observer groups as shortlisted below are required to fill EMOC 02 Forms and submit the full names of their officials and the State of deployment to the Election Monitoring and Observation Unit, INEC. Please note that EMOC 02 Form is obtainable at INEC Headquarters, Abuja and your submissions should be made on or before Friday, 25th March, 2011. S/N ORGANISATION LOCATION & ADDRESS 1 CENTER FOR PEACEBUILDING $ SOCIO- HERITAGE HOUSE ILUGA QUARTERS HOSPITAL ECONOMIC RESOURCES ROAD TEMIDIRE IKOLE EKITI DEVELOPMENT(CEPSERD) 2 COMMITTED ADVOCATES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEV SUITE 18 DANOVILLE PLAZA GARDEN ABUJA &YOUTH ADVANCEMENT FCT 3 LEAGUE OF ANAMBRA PROFESSIONALS 86A ISALE-EKO WAY DOLPHIN – IKOYI 4 YOUTH MOVEMENT OF NIGERIA SUITE 24, BLK A CYPRIAN EKWENSI CENTRE FOR ARTS & CULTURE ABUJA 5 SCIENCE & ECONOMY DEV. ORG. SUITE KO5 METRO PLAZA PLOT 791/992 ZAKARIYA ST CBD ABUJA 6 GLOBAL PEACE & FORGIVENESS FOUNDATION SUITE A6, BOBSAR COMPLEX GARKI 7 CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC ENRICHMENT 2 CASABLANCA ST. WUSE 11 ABUJA 8 GREATER TOMORROW INITIATIVE 5 NSIT ST, UYO A/IBOM 9 NIG. LABOUR CONGRESS LABOUR HOUSE CBD ABUJA 10 WOMEN FOR PEACE IN NIG NO. 4 MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY KADUNA 11 YOUTH FOR AGRICULTURE 15 OKEAGBE CLOSE ABUJA 12 COALITION OF DEMOCRATS FOR ELECTORAL 6 DJIBOUTI CRESCENT WUSE 11, ABUJA REFORMS 13 UNIVERSAL DEFENDERS OF DEMOCRACY UKWE HOUSE, PLOT 226 CENSUS CLOSE, BABS ANIMASHANUN ST. -

Policy Levers in Nigeria

CRISE Policy Context Paper 2, December 2003 Policy Levers in Nigeria By Ukoha Ukiwo Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, CRISE Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Executive Summary This paper identifies some prospective policy levers for the CRISE programme in Nigeria. It is divided into two parts. The first part is a narrative of the political history of Nigeria which provides the backdrop for the policy environment. In the second part, an attempt is made to identify the relevant policy actors in the country. Understanding the Policy Environment in Nigeria The policy environment in Nigeria is a complex one that is underlined by its chequered political history. Some features of this political history deserve some attention here. First, despite the fact that prior to its independence Nigeria was considered as a natural democracy because of its plurality and westernized political elites, it has been difficult for the country to sustain democratic politics. The military has held power for almost 28 years out of 43 years since Nigeria became independent. The result is that the civic culture required for democratic politics is largely absent both among the political class and the citizenry. Politics is construed as a zero sum game in which the winner takes all. In these circumstances, political competition has been marked by political violence and abandonment of legitimacy norms. The implication of this for the policy environment is that formal institutions and rules are often subverted leading to the marginalization of formal actors. During the military period, the military political class incorporated bureaucrats and traditional rulers in the process of governance. -

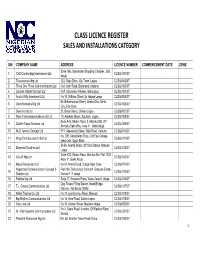

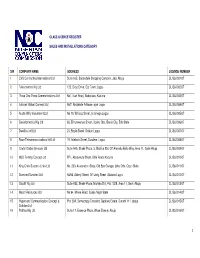

Class Licence Register Sales and Installations Category

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENCE NUMBER COMMENCEMENT DATE ZONE Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd CL/S&I/001/07 Abuja 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd CL/S&I/006/07 City, Edo State 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd CL/S&I/009/07 Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd CL/S&I/011/07 Ijebu Ode, Ogun State 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd CL/S&I/012/07 Lagos Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd CL/S&I/013/07 Area 11, Garki Abuja 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, 15 CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd Durumi 111, abuja 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 Opp Texaco Filing Station, Head Bridge, 17 T.J. -

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Nigeria Nigeria at a Glance: 2005-06

Country Report Nigeria Nigeria at a glance: 2005-06 OVERVIEW The president, Olusegun Obasanjo, and his team face a daunting task in their efforts to push through long-term, sustainable economic reforms in the coming two years. However, the recent crackdown on high-level corruption seems to point to the president!s determination to use his final years in power to shake up Nigeria!s political system and this should help the reform process. Given the background of ethnic and religious divisions, widespread poverty, and powerful groups with vested interests in maintaining the current status quo, there is a risk that the reform drive, if not properly managed, could destabilise the country. Strong growth in the oil and agricultural sectors will ensure that real GDP growth remains reasonably high, at about 4%, in 2005 and 2006, but the real challenge will be improving performance in the non-oil sector, which will be a crucial part of any real attempt to reduce poverty in the country. Key changes from last month Political outlook • There have been no major changes to the Economist Intelligence Unit!s political outlook. Economic policy outlook • There have been no major changes to our economic policy outlook. Economic forecast • New external debt data for 2003 show that the proportion of Nigeria!s debt denominated in euros was much higher than previously estimated. Owing to the weakness of the US dollar against the euro since 2003, this has pushed up Nigeria!s debt stock substantially, to US$35bn at the end of 2003. Despite limited new lending, mainly from multilateral lenders, we estimate that further currency revaluations and the addition of interest arrears to the short-term debt stock will push total external debt up to US$39.5bn by the end of 2006. -

![Human Rights and Democracy [In Nigeria]: Agenda for a New Era](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0367/human-rights-and-democracy-in-nigeria-agenda-for-a-new-era-1320367.webp)

Human Rights and Democracy [In Nigeria]: Agenda for a New Era

AfriHeritage Occasional Paper Vol 1. No1. 2019 AfriHeritage Occasional Paper Vol 1. No1. 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRACY [IN NIGERIA]: AGENDA FOR A NEW ERA By Chidi Anselm Odinkalu 1 AfriHeritage Occasional Paper Vol 1. No1. 2019 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. MEDIATING MULTI-DIMENSIONAL POLARITIES: IN SEARCH OF OUR BIG IDEA . 5 (a) Democracy, Counting and Accounting: The Idea of Political Numeracy ........... 8 (b) Democracy: The idea of Legitimacy .............................................................................. 11 (c) Human Rights: The Idea of Political Values ................................................................ 16 (d) Democracy and Digital Frisson: The Idea of Good Civic Manners ..................... 21 (a) Mis-Managing Diversity & Institutionalising Discrimination ............................... 28 (b) A Country that Cannot Count ......................................................................................... 34 (c) The Destruction of Accountability Institutions .......................................................... 40 (d) Legitimising Illegitimacy .................................................................................................... 44 4. ADDRESSING NIGERIA’S MULTIPLE CRISES OF STATEHOOD AND FRAGMENTATION -

Africa Confidential

5 March 1999 Vol 40 No 5 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL NIGERIA 2 NIGERIA Virtual voters UN and European Union monitors Soldier go, soldier come reckoned that Obasanjo's election President-elect Obasanjo's greatest challenge will be his plans to victory was seriously flawed but reform the military and end the putschist mentality 'generally reflected the will of the people'. Translated, that means The Nigerian conundrum - ‘it takes a soldier to end army rule’ - is to be tested again. General both sides rigged the vote but Olusegun Obasanjo, the choice of most army officers and the Western powers, was dubbed PDP Obasanjo's party was better at it (Pre-Determined President) - the acronym of his People’s Democratic Party. The 27 February and he would have won anyway. presidential election indeed had a pre-determined feel to it (see Box). But that’s not entirely surprising when Obasanjo faced an improbable coalition of erstwhile supporters of 1993 poll winner SOUTH AFRICA/USA 3 Moshood Abiola in the Alliance for Democracy and the All People’s Party (dubbed the Abacha People’s Party because so many of the late dictator’s acolytes had joined it). Within hours of his Transatlantic tryst victory, Obasanjo started choosing the transition committee which is to handle policy and appointments Washington now has closer up to the formal handover to civilian rule on 29 May. His hotel suite in Abuja has been overflowing relations with the ANC government with well-wishers and office-seekers. than with any other in Africa, A paid-up Nigerian nationalist, Obasanjo makes his priority to build a team that brings in the including Egypt and Morocco. -

The Culture of Military Clampdown on Youth Demonstrations and Its Repercussions on the 21ST Century Nigerian Youths

European Scientific Journal September 2018 edition Vol.14, No.26 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Dead or Dormant? Docile or Fractured? The Culture of Military Clampdown on Youth Demonstrations and its Repercussions on the 21ST Century Nigerian Youths Charles E. Ekpo Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies, University of Ibadan, Nigeria Cletus A. Agorye History & International Studies, University of Calabar, Nigeria Doi:10.19044/esj.2018.v14n26p74 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n26p74 Abstract The history of military regimes in Nigeria is synonymous with the history of suppression, repression, extricable use of violence, impunity and blatant trampling on fundamental human rights. Exclusive of J. T. U. Ironsi’s short six months in office, every military dictator in Nigeria had propelled himself to the rein through dubious and anti-people means. It was therefore not fortuitous that these praetorian guards, possessing the powers of ‘life and death’, trampled on, subdued, and caged the ‘bloody civilians’ whose social contract they had successfully usurped. Being the most affected, Nigerian youths had in several scenarios, occasions and events staged protests, demonstrations and marches to register their discontentment and resentment towards the military dictatorships. The reactions from the military governments were always violent, brutal, dreadful and aptly horrific. Military regimes went extra miles to enforce authority, legitimacy and acceptability. Whether through killing, maiming, blackmailing, bribing or threats, the youths had to be forced or cajoled into submission. This work focuses on military clampdown on youth demonstrations during the military era. It argues that the various repressive regimes had nurtured a docile and sycophantic youths who either display lackadaisical attitude over issues bothering social contract or are ignorant and nonchalant about governance in the country. -

CHRISTIANITY of CHRISTIANS: an Exegetical Interpretation of Matt

CHRISTIANITY OF CHRISTIANS: An Exegetical Interpretation of Matt. 5:13-16 And its Challenges to Christians in Nigerian Context. ANTHONY I. EZEOGAMBA Copyright © Anthony I. Ezeogamba Published September 2019 All Rights Reserved: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. ISBN: 978 – 978 – 978 – 115 – 7 Printed and Published by FIDES MEDIA LTD. 27 Archbishop A.K. Obiefuna Retreat/Pastoral Centre Road, Nodu Okpuno, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State, Nigeria (+234) 817 020 4414, (+234) 803 879 4472, (+234) 909 320 9690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.fidesnigeria.com, www.fidesnigeria.org ii DEDICATION This Book is dedicated to my dearest mother, MADAM JUSTINA NKENYERE EZEOGAMBA in commemoration of what she did in my life and that of my siblings. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge the handiwork of God in my life who is the author of my being. I am grateful to Most Rev. Dr. S.A. Okafor, late Bishop of Awka diocese who gave me the opportunity to study in Catholic Institute of West Africa (CIWA) where I was armed to write this type of book. I appreciate the fatherly role of Bishop Paulinus C. Ezeokafor, the incumbent Bishop of Awka diocese together with his Auxiliary, Most Rev. Dr. Jonas Benson Okoye. My heartfelt gratitude goes also to Bishop Peter Ebele Okpalaeke for his positive influence in my spiritual life. I am greatly indebted to my chief mentor when I was a student priest in CIWA and even now, Most Rev. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT DECEMBER 29, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt.