The Names of Pens Made in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

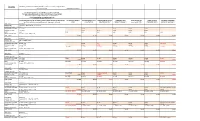

BID TABULATION #2836 OFFICE SUPPLIES Req/PO #: 176688

BID TABULATION #2836 OFFICE Req/PO #: 176688 2/19/21 SUPPLIES PYRAMID SOUTHWEST ACCO SCHOOL & OFFICE LN Qty Unit Description/Product ID BRANDS BRAND BRAND SCHOOL BRAND QUILL BRAND OFFICE BRAND DEPOT USA PRODUCT SUPPLIES S 1 96 EA 1510015 NO BID $3.81 $3.72 07 $5.60 8 $4.40 03 WASTEBASKET, RECTANGULAR PLASTIC 12 3/4"DIA X 16 2818BK 12/CAS 1/4"H, 7 GALLON, GRAY OR BLACK E BLACK ,***1510015 99 OR EQUAL 01 RUBBERMAID #2830 02 LOMA 823 03 RUBBERMAID 2956 0415X11X15 TENEX RECTANGULAR16024 RECT. 7 05GAL RUBBERMAID 69179 06 RUBBERMAID 69176 07(BLACK) CONTINENTAL 221-481 2818BK 08 COASTWIDE 124867 2 96 EA 1510035 NO BID $3.41 99 NO BID NO BID $3.55 04 BOOK, CLASS RECORD, TEACHER'S, K-12, SPIRAL WARD BOUND ,***1510035 HUBBARD HUB910L SKU#365 930 99 OR APPROVED EQUAL ***Wasn 01 GEOGRAPHY WORK BOOK 02COMPANY EASTMAN #201 ER110 03 WEBBER P3-206030 04 IMPERIAL 11300 PYRAMID SOUTHWEST ACCO SCHOOL & OFFICE LN Qty Unit Description/Product ID BRANDS BRAND BRAND SCHOOL BRAND QUILL BRAND OFFICE BRAND DEPOT USA PRODUCT SUPPLIES S 051510015 HAMMOND & STEVENS 610- 06PWASTEBASKET, ELAN R1010 RECTANGULAR PLASTIC 12 3/4"DIA X 16 1/4"H,07 TOPS41200 7 GALLON, (524- GRAY OR 3 2100 PKG BLACK1510040975)/NOT ,***1510015 ACCEPTABLE NO BID $17.16 NO BID $5.22 5 $6.50 06 BOOK, COMPOSITION, 40 SHEET/80PAGE ,10 X 8", EACH LINNET COVERING, FAINT PRICE RULING, 12 PER ,***1510040 99 OR EQUAL 02 MEAD 09-4075 03 CLASSMATE #1040 04 PRUDENTIAL FEIDCO 0522571 AVERY 43-461 06 IMPERIAL 1142 40M 07 EVERETTE 1040 11 SOUTHWEST 114240M 4 300 PKG 1510045 NO BID $3.58 99 NO BID NO BID $3.90 08 BOOK, DAILY LESSON PLAN 11 X 9 3/8", 52 SHEETS, WARD TWIN WIRE, 7 PERIODS HUBBARD ,***1510045 HUB18 SKU#365 846 99 OR EQUAL ***Wasn 01 WESTAB INC #50-1500 02 MEAD 50-1500 03 G W SCHOOL SUPPLY 04 PAC. -

Certified Products List

THE ART & CREATIVE MATERIALS INSTITUTE, INC. Street Address: 1280 Main St., 2nd Floor Mailing Address: P.O. Box 479 Hanson, MA 02341 USA Tel. (781) 293-4100 Fax (781) 294-0808 www.acminet.org Certified Products List March 28, 2007 & ANSI Performance Standard Z356._X BUY PRODUCTS THAT BEAR THE ACMI SEALS Products Authorized to Bear the Seals of The Certification Program of THE ART & CREATIVE MATERIALS INSTITUTE, INC. Since 1940, The Art & Creative Materials Institute, Inc. (“ACMI”) has been evaluating and certifying art, craft, and other creative materials to ensure that they are properly labeled. This certification program is reviewed by ACMI’s Toxicological Advisory Board. Over the years, three certification seals had been developed: The CP (Certified Product) Seal, the AP (Approved Product) Seal, and the HL (Health Label) Seal. In 1998, ACMI made the decision to simplify its Seals and scale the number of Seals used down to two. Descriptions of these new Seals and the Seals they replace follow: New AP Seal: (replaces CP Non-Toxic, CP, AP Non-Toxic, AP, and HL (No Health Labeling Required). Products bearing the new AP (Approved Product) Seal of the Art & Creative Materials Institute, Inc. (ACMI) are certified in a program of toxicological evaluation by a medical expert to contain no materials in sufficient quantities to be toxic or injurious to humans or to cause acute or chronic health problems. These products are certified by ACMI to be labeled in accordance with the chronic hazard labeling standard, ASTM D 4236 and the U.S. Labeling of Hazardous NO HEALTH LABELING REQUIRED Art Materials Act (LHAMA) and there is no physical hazard as defined with 29 CFR Part 1910.1200 (c). -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015 1. How did you find out about this survey? Other 17% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% 539 Other 17.0% 110 Total 649 1 2. Where are you from? Australia/New Zealand 3.2% Asia 3.7% Europe 7.9% North America 85.2% North America 85.2% 553 Europe 7.9% 51 Asia 3.7% 24 Australia/New Zealand 3.2% 21 Total 649 2 3. What is your age range? old fart like me 15.4% 21-30 22% 51-60 23.3% 31-40 16.8% 41-50 22.5% Statistics 21-30 22.0% 143 Sum 20,069.0 31-40 16.8% 109 Average 36.6 41-50 22.5% 146 StdDev 11.5 51-60 23.3% 151 Max 51.0 old fart like me 15.4% 100 Total 649 3 4. How many fountain pens are in your collection? 1-5 23.3% over 20 35.8% 6-10 23.9% 11-20 17.1% Statistics 1-5 23.3% 151 Sum 2,302.0 6-10 23.9% 155 Average 5.5 11-20 17.1% 111 StdDev 3.9 over 20 35.8% 232 Max 11.0 Total 649 4 5. How many pens do you usually keep inked? over 10 10.3% 7-10 12.6% 1-3 40.7% 4-6 36.4% Statistics 1-3 40.7% 264 Sum 1,782.0 4-6 36.4% 236 Average 3.1 7-10 12.6% 82 StdDev 2.1 over 10 10.3% 67 Max 7.0 Total 649 5 6. -

Principles of Cartooning I Jonathan H. Gray

Principles of Cartooning I Jonathan H. Gray Room: 703G, 2nd Ave Building | Code: CID-2000-C | Fall Semester: 3-Studio Credits | Meet: Every Wednesday Time: 3:20-6:10 PM | Office Hrs: Wed, by appt (class or email) | Email: [email protected] | Web: www.jongraywb.com SYLLABUS: CID-2000-C – FS 18-SP19- Gray, J. COURSE DESCRIPTION AKA: What to Expect In this course we will examine the fundamental understandings and principles of the professional field of cartooning from a formal analysis of how the aesthetics of a comic’s construction can help to promote its content. We will become familiar with and experience the basics of cartooning as well as allow exploration towards the wealth of options available to you as you pursue this field. There are several things that the student is expected to understand by the end of this course: What methods and media can I employ towards creating? What is the story I wish to create and how will basic design, composition and functionality come together in my imagery? What are practical business aspects will I need to become a professional cartoonist? How can I employ and juggle critical thinking and problem-solving skills in both my artwork and my business? All areas of cartooning craft and writing will be covered, from page and panel layout and composition, to inking and drawing skills, to your thoughts and ideas in constructing a narrative and how they relate to the outside cartooning and cultural universes. Each student is responsible for constructing a narrative of their own device, keeping a sketch journal of their progress from start to finish and composing fifteen pages (minimum) of their story (or stories), plus one cover for it, each semester. -

Instructions: We Do Not Guarantee the Required Quantities As These Are Estimates Only; Based on an Annual Demand

Instructions: We do not guarantee the required quantities as these are estimates only; based on an annual demand. Q7099 Pencils, Pens, Erasers Complete the fields that are highlighted in orange in Column D. To prevent disqualification do not alter the formatting on the worksheet. All anticipated orders will be placed on an “as needed basis”. Once the spreadsheet is complete email it to: [email protected] Pricing must remain firm for 12 months, and must include all costs including freight, AFP Industries Miami Fl Brown & Saenger Sioux COMMERCIAL ART SUPPLY PYRAMID SCHOOL School Specialty Inc SMITH OFFICE & STANDARD STATIONERY the District will not pay any additional costs for products delivered. 33280 Falls/SD/57118 SYRACUSE, NY 13210 PRODUCTS TAMPA FL Lancaster, PA 17601 COMPUTER SUPPLY SUPPLY CO WHEELING IL DMPS SKU# S002003870 DESCRIPTION PENCIL BOX, Clear Hinged Lid, .5" x 5.5" x 2.5" ESTIMATED USAGE 348 MANUFACTURER NAME AVT-34104 As Spec No Bid No Bid No Bid MANUFACTURER# AVT-34104 As Spec No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid UOM EACH EACH EACH EACH EACH EACH EACH EACH PREVIOUS YEAR PRICE Office Max - $1.50 - q6840 - 2014 QUOTE PRICE $0.000 $1.520 $0.000 $0.000 $0.000 $0.000 $0.000 DMPS SKU# S015046021 DESCRIPTION Eraser, Kneadable Rubber, ESTIMATED USAGE 24 MANUFACTURER NAME Leonard 71585 As Spec ACI As Spec No Bid No Bid EASY ERASE MANUFACTURER# Leonard 71585 As Spec A1224 As Spec No Bid No Bid 1224 UOM dz, 12/bx dz, 12/bx dz, 12/bx dz, 12/bx dz, 12/bx dz, 12/bx dz, 12/bx dz, 12/bx PREVIOUS YEAR PRICE Pyramid - $3.49 - q6855 -

BBB-Summer-2018-Large.Pdf

‘Modern’ calligraphy has been making the rounds lately and if you're here — that's probably what you want to learn! But before we get all into the details, here's one thing you need to remember: calligraphy is not cursive. Cursive is joined up writing; you ideally write without li�ting your pen so you can write faster. While calligraphy can look similar, the key is to go slow and to break down each and every letter into its supporting strokes. THE BASIC STROKES ASCENDER LINE WAIST LINE BASE LINE DESCENDER LINE Or as some people call them, the drills! As dull as it sounds, brush lettering is made up of 9 common strokes illustrated above. With these strokes alone, you can form 21 out of the 26 letters in the lowercase alphabet — and some of the capital letters too! HOW THIS WORKS In Brush Basics, we'll be building your foundation right by covering all 9 strokes over the course of 2 weeks! Here's the schedule: On Day 1, you'll learn how to use your brush pen to form thin upstrokes and thick downstrokes. This is an easy lesson, so you have just one day to tackle it! Lesson 2 (delivered on Day 2) will cover underturn and overturn strokes. Lessons 3 and 4 (delivered on Days 4 and 6, respectively) will see you taking on the two di�ferent compound curves. You'll learn all about ovals in Lesson 5 (delivered on Day 8) — and because this is a hard one, you'll have not two but three days to practice it. -

Pens Bequeathed to the Nso by David Ogden Stiers

PENS BEQUEATHED TO THE NSO BY DAVID OGDEN STIERS * = in original box Item # Brand Description Made in Type / Price AN 105 Ancora Paua Mother of Pearl 43/888 Italy FP* Brownish orange/green pearl in shaft $400 AN 572-SOLDAncora Ravenna 49/1919 Italy FP Damaged on green pearl shaft SOLD AU 93-SOLD Aurora (SET) Optima Sole #3629 Italy FP* Yellowish orange AU 95-SOLD Aurora (SET) Optima Sole #3629 Italy BP - Twist SET of 2 SET SOLD AU 128 Aurora Dante Alighieri #70 Italy FP* Limited Edition Green Vermil $850 AU 516-SOLD Aurora Optima Italy FP Black with gold key band worn SOLD Ban 15 Ban ie Kamakura Bori Urushi Japan FP* Black & brown $600 Ban 18 Ban ie Nashiji Nuri Japan FP* Black-gold specks $600 Bex 38 Bexley (SET) Cable Twist Pen USA FP Platium Convertible Bex 39 Bexley (SET) Cable Twist Pen USA BP* PENS BEQUEATHED TO THE NSO BY DAVID OGDEN STIERS Platium Convertible SET of 2 SET $200 Bex 438 Bexley (SET) Cable Twist - Honey 24/50 USA FP* Bex 440 Bexley (SET) Cable Twist - Honey w/cap USA BP* SET of 2 SET $250 Bex 449 Bexley Deco band gold 24/50 USA FP Grainwood ebonite $150 Bex 451 Bexley Blue w/ gold clip USA FP $85 Bex 574 Bexley Imperial- gray USA FP $80 Bex 591-SOLD Bexley Black amber marble USA FP SOLD Bex 598 Bexley Imperial - redishbrown USA FP $80 C 342 Carters Snakeskin blue-pump USA FP $65 Con 344 Conklin Nozac USA FP 12 sided redishbrown marble $275 Con 431 Conklin Tan celluloid USA FP $90 PENS BEQUEATHED TO THE NSO BY DAVID OGDEN STIERS Con 576 Conklin Nozac - 8 sided orange lava swirl USA FP $225 Con 578 Conklin Mark Twain- -

Classification of Colouring / Writing Instruments and Related Art & Craft

European Writing Instrument Manufacturer’s Association Classification of Colouring / Writing Instruments and related Art & Craft Materials as Toys PRATERSTRASSE 34 · D-90429 NÜRNBERG · GERMANY Tel.: +49-(0) 911 / 27 229-0 · Fax +49-(0) 911 / 27 229-11 Email: [email protected] · Website: www.ewima.org European Writing Instrument Manufacturer’s Association 1 Products considered as „Toys“ - Chalks - Coloured pencils - Fibre pens - Finger paints - Drawing games (spiro games) - Modelling materials - Water colours - Wax crayons - Window colour - Fancy products [all products specially designed (e.g. by their shape) or clearly intended (e.g. by their packaging) for use in play by children under 14 years of age] “Toy”: Product designed or intended, whether or not exclusively, for use in play by children under 14 years of age. (As defined by European directive 2009/48/EC “safety of toys”, Art.2 No. 1). The final classification (product by product) and its inherent obligations, are the sole responsibility of each individual manufacturer, his authorized representative or importer. Products finally classified as toys by the manufacturer, his authorized representative or importer must comply with the essential safety requirements in Annex II of the directive or have successfully passed one of the conformity assessment procedures. The essential safety requirements are partially specified in the harmonized EN 71-series (all relevant parts). The products finally classified as toys must be marked with the CE-marking on the product itself or on the packaging. -

Brands and Product Lines & Website Guide

plus Brands and Product Lines & Website Guide starts on page 56 Last Updated April 5, 2021 CONTACT [email protected] with questions, corrections, additions, updates Page 2 of 67 Product Guide Acetate Sheets Rolls Pads Grafix Jacquard Products / Rupert, Gibbon & Spider, Inc. MacPherson's SLS Arts Texas Art Supply/Art Supply Network Adhesives Alvin & Company Atlas Tape - Channeled Resources Grafix Grex Airbrush H. Schmincke & Co. GmbH & Co. KG HK Holbein, Inc Imagination International Jacquard Products / Rupert, Gibbon & Spider, Inc. Lineco MacPherson's Newell Brands SLS Arts Speedball Art Products Tombow Yasutomo Ziller's, LLC Advertising Art Materials Retailer Magazine Airbrush Equipment and Supplies Armadillo Art & Craft Grafix Grex Airbrush H. Schmincke & Co. GmbH & Co. KG HK Holbein, Inc Iwata-Medea Inc. Jacquard Products / Rupert, Gibbon & Spider, Inc. Page 3 of 67 MacPherson's SLS Arts SINOART Shanghai Co., Ltd Texas Art Supply/Art Supply Network Ziller's, LLC Albums Art and Photo Hahnemuhle USA Lineco MacPherson's SLS Arts Texas Art Supply/Art Supply Network Uchida of America Architectural Supplies ACCO UK. - ACCO Brands, Derwent Alumicolor Alvin & Company Grafix Jack Richeson & CO Inc. MacPherson's SINOART Shanghai Co., Ltd SLS Arts STAEDTLER-Mars Limited Studio Designs Texas Art Supply/Art Supply Network Tombow Artboard MultiMedia Aitoh Co. (WCG Group LLC, dba Aitoh Co.) Alvin & Company Crescent Cardboard, LLC Fredrix Canvas Grafix Heinz Jordan and Company Limited Hilltop Paper LLC Jack Richeson & CO Inc. Lineco Ranger Industries SINOART Shanghai Co., Ltd SLS Arts Texas Art Supply/Art Supply Network Block Printing ABIG GERMANY Armadillo Art & Craft Cranfield Colours Page 4 of 67 Educational Art and Craft Supplies Edward C Lyons Co. -

The Influence of Writing Instruments on Handwriting and Signatures*

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 60 | Issue 1 Article 12 1969 The nflueI nce of Writing Instruments on Handwriting and Signatures Jacques Mathyer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Jacques Mathyer, The nflueI nce of Writing Instruments on Handwriting and Signatures, 60 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 102 (1969) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE JouNAL or CImiNAL LAW, CRIUINOLOGY AND POLICE SCIENCE Vol. 60, No. 1 Copyright © 1969 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. THE INFLUENCE OF WRITING INSTRUMENTS ON HANDWRITING AND SIGNATURES* JACQUES MATHYER Professor Jacques Mathyer received the Diploma in Police Science (Criminalistics) in 1946 from the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and the Diploma in Criminology in 1957. During 1946-1947 he was assistant to Dr. Edmond Locard in Lyons, France, where he received his Doctor of Science Degree from the University of Lyons, 1947. After serving in the police laboratory of Vaud, Lausanne, Switzerland, he served from 1949 to 1963 as assistant to Professor Marc A. Bischoff at Institut de police scientifique et de criminologie of the University of Lausanne. Upon Professor Bischoff's re- tirement in 1963 he was named Professor and Director of the Institute.