Folk - Etymology: How to Make Words with Their False Counterparts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk Taxonomy, Nomenclature, Medicinal and Other Uses, Folklore, and Nature Conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3

Ulicsni et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2016) 12:47 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0118-7 RESEARCH Open Access Folk knowledge of invertebrates in Central Europe - folk taxonomy, nomenclature, medicinal and other uses, folklore, and nature conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3 Abstract Background: There is scarce information about European folk knowledge of wild invertebrate fauna. We have documented such folk knowledge in three regions, in Romania, Slovakia and Croatia. We provide a list of folk taxa, and discuss folk biological classification and nomenclature, salient features, uses, related proverbs and sayings, and conservation. Methods: We collected data among Hungarian-speaking people practising small-scale, traditional agriculture. We studied “all” invertebrate species (species groups) potentially occurring in the vicinity of the settlements. We used photos, held semi-structured interviews, and conducted picture sorting. Results: We documented 208 invertebrate folk taxa. Many species were known which have, to our knowledge, no economic significance. 36 % of the species were known to at least half of the informants. Knowledge reliability was high, although informants were sometimes prone to exaggeration. 93 % of folk taxa had their own individual names, and 90 % of the taxa were embedded in the folk taxonomy. Twenty four species were of direct use to humans (4 medicinal, 5 consumed, 11 as bait, 2 as playthings). Completely new was the discovery that the honey stomachs of black-coloured carpenter bees (Xylocopa violacea, X. valga)were consumed. 30 taxa were associated with a proverb or used for weather forecasting, or predicting harvests. Conscious ideas about conserving invertebrates only occurred with a few taxa, but informants would generally refrain from harming firebugs (Pyrrhocoris apterus), field crickets (Gryllus campestris) and most butterflies. -

The Folk Etymology in Greek Dialects: a First Approach

The folk etymology in Greek dialects: A first approach ASIMAKIS FLIATOURAS Democritus University of Thrace 1. Definition and research points1 Paretymology constitutes the psycholinguistic2 mechanism of analogical change3 which leads to the false connection of a lexical unit to another, thus resulting in a change in form and/or meaning with the objective of morphosemantic transparency, e.g. TK yuvarlak ‘type of meatball’ > GK γiuvareláki [varéli ‘barrel’], ΜEG eγóklima ‘honeysuckle’ > MG aγióklima [áγios ‘holy’]4 (see inter alia Förstermann 1852; Orr 1953; Mayer 1962; Baldinger 1973; Olschansky 1996; Rundblad & Kronenfeld 2000; Michel 2015, for the Greek language, see Chatzidakis 1915-6: 172-173; Μoysiadis 2005: 250-4; Μoysiadis & Katsouda 2011; Fliatouras, Voga & Anastassiadis-Syméonidis forthcoming; Fliatouras 2017). The term folk etymology which prevails in Greek bibliography is misleading. “Paretymology” is preferred, given that the mechanism may lead to more learned formations because of hypercorrection or scholar intervention in more familiar types (see also Béguelin 2002). Furthermore, it is a hypernym term and thus it may stipulate all cases; both conscious, such as the ludative/playful5 and the normative paretymology; and unconscious, namely folk etymology (for more details see Fliatouras 2017). In this paper, paretymology is equated with folk etymology, since it is the prototypical case for Greek dialects. Ludative paretymology is traced with difficulty, as reading of dialectic texts is required and usually these types are not registered in dictionaries (e.g. CR ma ton θeó ‘I swear to God’ > ma ton xiló ‘I swear to pulp’ as a type of joke to make an oath looser), and the normative paretymology is rare, given that the reasons which render it productive in Standard Greek are not compatible with the dialects6. -

Revisiting the Question of Etymology and Essence

Revisiting the question of etymology and essence The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2016. "Revisiting the question of etymology and essence." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/revisiting-the-question- of-etymology-and-essence/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40827377 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:CHS.Online_Publishing for a complete and continually expanding list of open access publications by CHS. -

Linguistic Colonialism in Aeschylus' Aetnaeae Carol Dougherty

DOUGHERTY, CAROL, Linguistic Colonialism in Aeschylus' "Aetnaeae" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 32:2 (1991:Summer) p.119 Linguistic Colonialism in Aeschylus' Aetnaeae Carol Dougherty EW DIRECTIONS in Shakespearean scholarship have com N plicated our understanding of the relationship between the plays of Shakespeare and important historical events of the seventeenth century, such as colonization of the New World, and the results are dramatic. Interpretations of The Tempest, for example, which once focused on Prospero as the consummate artist (a stand-in perhaps for the bard) in final celebration of the power and glory of great Ii terature and the English empire, have now taken a darker, more sinister turn: Prospero, master of the theater, becomes a problematic force of imperialism; Ariel nearly disappears from sight as Caliban, the 'noble savage', representing the indigenous populations sacrificed for the sake of imperial expansion, usurps the critical spotlight. Many of these 'new historical' readings of The Tempest find an ambivalent attitude toward colonization embedded in the play, connecting it to the critical role that language plays in the establishment of empire. In support of this view, Stephen Greenblatt, for example, describes Queen Isabella's puzzled reaction to the first modern European grammar: In 1492, in the introduction to his Gramdtica, the first grammar of a modern European tongue, Antonio de Nebrija writes that language has always been the partner ("com paiiera") of empire. And in the ceremonial presentation of the volume to Queen Isabella, the bishop of Avila, speaking on the scholar's behalf, claimed a still more central role for language. -

From Iranian Myth to Folk Narrative the Legend of the Dragon-Slayer and the Spinning Maiden in the Persian Book of the Kings

K in ga Ilona MArkus-Takeshita Independent scholar Sagamihara, Japan From Iranian Myth to Folk Narrative The Legend of the Dragon-Slayer and the Spinning Maiden in the Persian Book of the Kings Abstract This study of an episode in the latter part of Ferdawsi’s version of the Iranian national epic demonstrates how a composite folktale is incorporated into the quasi-historical nar rative. Ardasir, founder of the Sasanid dynasty and the second Persian empire (224—651 CE), is challenged in his conquests by Haftvad, the ruler of Kerman, whose fortune has been assured by a worm that his daughter found in an apple while spinning yarn, and nurtured until it grew into a talismanic dragon. Ardasir wins by a ruse, entering the enemy castle disguised as a merchant who desires to feed the worm, which he kills by feeding it molten metal instead of rice. Alternative versions of the tale (the Pahlavi gesta of Ardasir, the Arabic annals of Tabari) supplement the Shahnama narrative. The episode comprises the folktale types of the Dragon-Slayer (Type 300) and the Magic Spinner (Type 500),incorporating several folktale motifs. Parallels from world folklore in prior studies are noted and new ones proposed. Ferdawsi,s narrative, while it successfully combines a foundation legend with tales respectively of male and of female initiation, is interpreted within its own mytho-historical context as a cautionary tale that supports divinely-sanctioned imperial authority (farr) and opposes the autonomy of commoners supposedly favored by a local deity (baxt), thus promoting religious orthodoxy over heterodoxy. Keywords: Shahnama— Persian history and legend— Dragon-Slayer~Magic Spinner— Kerman Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 60,2001: 203-214 HE STORY OF THE WORM is the closing episode of the chapter on the Askani (Arsacid) rulers in Ferdawsi’s Shahnama. -

Anton Salmin Why Is the Term Folk Religion Unrecognized in Russia?

ANTON SALMIN WHY IS THE TERM FOLK RELIGION UNRECOGNIZED IN RUSSIA? Anton Salmin Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint-Petersburg, Russia. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Both folk and world religions always focus on Homo religiosus. As long as a person takes part in ritual ceremonies, such a person is certainly religious. Thus, the rite precedes the concept of “belief”. However, the concept of belief came forward in religious acts during the development of the Reformation. For example, in Japan, the folk religion was denoted by the term minkan shinkō “folk beliefs”. Therefore we can state that, in ancient times, folk religion brought people and communities together much better than the world religions separated from each other. Moreover, ancient religions played a consolidating role to a larger extent than ethnic languages. The reason is the syncretism of folk religion. The need for this publication is dictated by irreparable problems arising in Russian Ethnography. The author believes that no further progress in ethnology (socio-cultural anthropology) is possible unless the problem mentioned in the headline is removed from the agenda. Without bringing light to the problem or finding an appropriate solution, we will come to a standstill or pretend that the problem does not exist at all. The author of these lines does not incline to obtrude his own opinion. The goal of the publication is to provide a critical analysis of existing and a priori established opinions. Let us observe the bunch of views presented in Western sources (in which the problem seems to be much less severe, at least – much less vague), and then compare with the ones existing in Russia. -

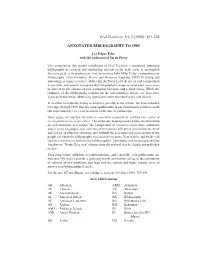

Annotated Bibliography to 1985

Oral Tradition, 3/1-2 (1988): 191-228 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY TO 1985 Lee Edgar Tyler with the assistance of Sarah Feeny This compilation, the second installment of Oral Tradition’s continuing annotated bibliography of research and scholarship relevant to the fi eld, seeks to accomplish the same goals as its predecessor: fi rst, to continue John Miles Foley’s comprehensive bibliography, Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research (Garland, 1985) by listing and annotating as many resources addressing the Parry-Lord theory of oral composition as possible; and second, to expand that compilation’s scope to cover even more areas of interest to the scholar of oral traditional literature and related forms. While the emphasis of the bibliography remains on the oral-formulaic theory, we have once again included entries addressing approaches other than the Parry-Lord Theory. In an effort to make this listing as useful as possible to the scholar, we have extended coverage through 1985; thus the annual publication of our installments will henceforth run approximately two years in arrears of the date of publication. Once again, we ask that all authors contribute regularly by sending two copies of recent publications to the editor. The extremely heterogeneous nature of scholarship on oral traditions necessitates the compilation of resources from most continents and in many languages. Our own research resources will prove insuffi cient to create and sustain an effective reference tool without the assistance and participation of the people for whom the bibliography was created—its users. Your articles and books will receive annotation in forthcoming bibliographies; your books and monographs will be listed in our “Books Received” column annually and will also be eligible for published review. -

Near-Eastern Echoes in Iliad XVI 33–35

1 Near-Eastern Echoes in Iliad XVI 33–35 Apostolia Alepidou In Iliad XVI, Patroclus, devastated by the numerous deaths and injuries inflicted on the Achaean army by Hector, approaches Achilles and accuses him of being idle in the face of the disaster: he insists on his wrath, although the situation demands for immediate intervention. Right before asking Achilles to let him instead join the war as the commander of the Myrmidons (Iliad XVI 36–45), Patroclus addresses his dear friend with some harsh words: νηλεές, οὐκ ἄρα σοί γε πατὴρ ἦν ἱππότα Πηλεύς, οὐδὲ Θέτις μήτηρ˙ γλαυκὴ δέ σε τίκτε θάλασσα πέτραι τ᾽ ἠλίβατοι,1 ὅτι τοι νόος ἐστὶν ἀπηνής. Pitiless one, your father, it appears, was not the horseman Peleus, nor was Thetis your mother, but the gray sea bore you, and the sheer cliffs, since your mind is unbending.2 Iliad XVI 33–35 Patroclus’ comment on Achilles’ parentage, unparalleled in Homer’s epic, is puzzling and difficult to interpret. “You were born from the sea and the rocks, not from Thetis and Peleus,” is what Patroclus tells Achilles, and even though the context leaves no doubt that this is a reproach to cruel and merciless Achilles, the interpretation of this phrase has troubled readers and scholars since antiquity. This paper aims to shed light on the origin and, consequently, the 1 My emphasis. 2 Translation by Murray 1999. 2 exact meaning of Iliad XVI 33–35, taking a close look at the common theme of a creature being born from the sea/the rocks that these lines from Iliad XVI and the traditions of ancient cultures in Near East share. -

Picturesque Faulknerisms

Studies in English Volume 9 Article 7 1968 Picturesque Faulknerisms George W. Boswell University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boswell, George W. (1968) "Picturesque Faulknerisms," Studies in English: Vol. 9 , Article 7. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Boswell: Picturesque Faulknerisms PICTURESQUE FAULKNERISMS by George W. Boswell During the 1960’s, with the single exception of Mark Twain, no American author has stimulated the production of more scholarly research than William Faulkner. Principal areas of treatment have been contributions to his biography, study of his fictional techniques, and the content and philosophy of his work. As he was also a master of language—representation of dialect and coinage of word and phrase—this paper will attempt to display some of this mastery and trace its origins under eight headings: pronunciation, names, diction, morphology, figurative language, syntax, titles of his books and short stories, and pro verbial expressions. As rendered by Faulkner, Southern Negro and poor-white pronunciation is characterized by four principal divergencies from standard English: omission of certain consonants, especially the r; substitution of certain vowels for others; omis sion of entire syllables; and certain intrusive consonants. The r is dropped in bob-wire (The Hamlet), liberry (The Mansion), reser- voy (Uncle Willy), to’a’ds for towards (Sartoris), and the follow ing Negro words: kahysene for kerosene (Dr. -

1535274406844.Pdf

Copyright © 2005 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504. The EuroSlavic fonts used to create this work are © 1986–2002 Payne Loving Trust. EuroSlavic is available from Linguist’s Software, Inc., www.linguistsoftware.com, P.O. Box 580, Edmonds, WA 98020-0580 USA tel (425) 775-1130. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Archetypes and motifs in folklore and literature : a handbook / edited by Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7656-1260-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Folklore—Classification. 2. Folk literature—Themes, motives. I. Garry, Jane. II. El-Shamy, Hasan M., 1938–GR72.56.A73 2004 398'.012—dc22 2004009103 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984. ~ MV (c)10987654321 Contents Illustrations xi Preface xiii Introduction xv How to Use This Book xxv About the Editors and Contributors xxxi A. Mythological Motifs Nature of the Creator, Motif A10 el-Sayed el-Aswad 3 The Hero Cycle, Various Motifs in A Natalie M. Underberg 10 Death or Departure of the Gods, Motif A192, and Return, Motif A193 Peter L. De Rose and Jane Garry 17 Creation Myth: Cosmogony and Cosmology, Motifs A600–A899 el-Sayed el-Aswad 24 Fight of the Gods and Giants, Motif A162.1 Deeksha Nagar 32 Doomsday (Day of Judgment), Motif A1002 Judith Neaman 38 Confusion of Tongues, Motif A1333 Jane Garry 43 Origin of Pentecost, Motif A1541.6 Judith Neaman 46 Origins of Inequality, Motifs A1600–A1699 D.L. -

Learned & Popular Etymology

PETUR KNOTSSON Learned & Popular Etymology: Prescription vs. Intertextual Paronomasia 1 In this paper I intend to complain about dismissive attitudes towards so-called popular or false etymology in loan-words and other cases, and propose instead the view that non-etymological echoic adaption of loans is typically intentional and paronomastic, of the same type as echoic retention of surface structure in textual transmission. In the clas- sical tradition of lexical speculation going back to Plato it constitutes an important aspect of intertextual signification. 1. "Popular etymology": Bloomfield's formulation Leonard Bloomfield's (1933) classic account of loan-words invokes the traditional concept of "popular etymology" to characterise adapted English loan-words such as groze-berry > gooseberry; asparagus> sparrow-grass; crevise > crayfish (Bloomfield 1935:450). He notes that the same process also occurs in the development of certain native terms in which obsolete forms have survived as fossils and thus become susceptible to the same changes; his examples are shamfast > shame- faced; samblind > sand-blind; bryd-guma > bridegroom. He comments (Bloomfield 1935:423): (1) So-called popular etymologies are largely adaptive and con- taminative. An irregular or semantically obscure form is re- placed by a new form of more normal structure and some semantic content - though the latter is often far-fetched. 1This is a revisedversion of a paper read at the 5th InternationalConferenceof the Nordic Associationof English Studies held in Reykjavikin July 1992.I am indebted to several colleagues for valuable comments and suggestions, and to the staff of the Instituteof Lexicographyfor someessentialguidance. .1 fslenskt mal 15(1993), 99-120. -

Religion, Ritual, and Ritualistic Objects’

religions Editorial Introduction to the Special Issue ‘Religion, Ritual, and Ritualistic Objects’ Albertina Nugteren Faculty of Humanities and Digital Sciences, Tilburg University, 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands; [email protected] Received: 13 February 2019; Accepted: 25 February 2019; Published: 6 March 2019 If an object-centered volume on religious ritual is anything, it is a collection of contributions on material culture as a manifestation of structured symbolic practices (Fleming and Mann 2014; Grimes 2011; Keane 2008; Morgan 2008). Such practices are assumed to be endowed with signification and to be based on an interrelated set of ideas. Rituals may be taken to exist because they perform the function of establishing a common mood and thus assert social solidarity, but a ritual has a particular style, is part of a cultural and symbolic order. Its material dimensions, particularly its objects, may provide us with keys to meaning-making. According to Hodder(1987, p. 1) the meaning in objects is threefold: (1) objects have use value through their effect on the world (a functionalist, materialistic, or utilitarian perspective); (2) objects have structural or coded meanings, which they communicate (their symbolic meaning); (3) objects are meaningful through their past associations (their historical meaning). Studying objects as transporters of meaning, as well as people’s responses to such objects, especially in ritual contexts, thus becomes a study not merely of culture-specific materiality (or: materialization, when the processual character is emphasized) but also of the multiple interpretations that occur when people and objects move from one context to another. We are fortunate that all authors in this Special Issue show a sensitive awareness of contexts and people’s responses to objects, and do not limit themselves to iconography, style, or symbolism.