A RETREAT for HOLY WEEK by Father Robbie Low

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roman Army at Arbeia

The Roman Army at Arbeia At the time Arbeia was built, the Roman army had conquered a large area, creating an Empire that stretched from Syria and North Africa to Scotland. A soldier’s main task was to defend the frontiers of Rome so they were well organised and well equipped. Roman soldiers were either legionaries or auxiliaries. Legionaries were at Arbeia to build the fort and left when it was finished, while auxiliaries garrisoned the fort for a further 250 years. A legionary soldier was a Roman citizen but an auxiliary soldier was not, auxiliary soldiers were recruited from the tribes that the Romans conquered. In this way, the Roman army was made up of people from all over the Roman Empire. Wherever they were from, Roman soldiers had to learn Latin as this was the language used in the army. An auxiliary solder could become a Roman citizen after years of loyal service or in return for particular acts of bravery. Both auxiliaries and legionaries were highly skilled soldiers. A Roman soldier’s life was hard and army discipline was strict. However, Roman soldiers were well paid so there was no shortage of young men wanting to join. Most soldiers stayed in the army for around 20 years. Roman soldiers were encouraged to keep themselves clean and fit. They kept fit by training in full amour with their weapons (around 2 hours a day) and by running. All soldiers were able to use the garrison’s Bath House to keep clean but they also used it for socialising and playing games. -

MARINES and MARINERS in the ROMAN IMPERIAL FLEETS Jasper

MARINES AND MARINERS IN THE ROMAN IMPERIAL FLEETS Jasper Oorthuijs Since Chester Starr’s 1941 book The Roman Imperial Navy it has become generally accepted knowledge that “the crew of each warship, regard- less of its size, formed one centuria under its centurio (classicus) in the manner of a legionary centuria.”1 Boldly stating his case, Starr solved one of the most problematic peculiarities in the epigraphic habit of Roman naval troops in one great swoop. The problem referred to is the following: in roughly two thirds of the exstant inscriptions milites of the imperial eets stated that they belonged to some kind of war- ship, while the other third indicated that they belonged to a centuria. A small number indicated neither and a very few referred to both ship and centuria. Starr’s statement was never challenged despite the prob- lems that clearly exist with this theory. In what follows some of those problems will be addressed. First of all, the consequence of Starr’s theory is that we have to accept the idea that centuriones classici commanded a great range of troops: ship’s crews ranged in size from some 50 men for a liburna up to 400 in quinqueremes.2 There are however no indications of different grades of centurio in the eets. Moreover, because Starr squeezes a naval and army hierarchy into one, the trierarchs and navarchs, whether captains or squadron commanders, have to be forced in somewhere. Starr him- self never seems to have found a satisfying solution for that problem and its practical results. -

Polybius and Livy on the Allies in the Roman Army

POLYBIUS AND LIVY ON THE ALLIES IN THE ROMAN ARMY Paul Erdkamp* From the fourth or third century until the beginning of the rst century bc, Rome’s armies were also the armies of her allies. The socii and nomen Latinum raised at least half of the soldiers that fought wars for Rome. The Italic allies were clearly distinguished from the non-Italic troops, such as Cretan archers or Numidian horsemen, by the fact that they were governed by the formula togatorum. This can be concluded from their ‘de nition’ in the lex agraria from 111 bc: socii nominisve Latini quibus ex formula togatorum milites in terra Italia imperare solent. The formula togatorum is seen as a de ning element, distinguishing the Latin and Italic peoples from Rome’s overseas allies. Although in the second century bc a con- sciousness of Italy as a political and cultural unity gradually emerged, it was still referred to as a military alliance of Roman citizens and allies at the end of that century.1 The beginnings of this system remain in the dark, due to the inadequacies of our sources. The foedus Cassianum between Rome and the Latin League (traditionally dated to 493 bc) supposedly established a federal army under Roman command, but next to nothing is known about its functioning. The participation of the allied peoples was based on the treaties between their communities and Rome. The position of the Latin colonies was slightly different, because their obligations were probably based on the lex coloniae governing each Latin colony.2 We may assume that the role of the allies was re-de ned * I wish to thank John Rich, Luuk de Ligt and Simon Northwood for their many valuable comments. -

Centurions in the Roman Legion: Computer Simulation and Complex Systems

Authors: Rubio-Campillo, Xavier1; Valdés, Pau2; Ble, Eduard2 Title: Centurions in the Roman Legion: Computer Simulation and Complex Systems 1 – Corresponding author, Barcelona Supercomputing Centre, [email protected] 2 – Universitat de Barcelona Abstract The Centurion was a key figure of Roman warfare over a span of several centuries. However, their real role in battle is still a matter of discussion. Historical sources suggest that their impact in the efficiency of the Roman battle line was highly disproportionate to their individual actions, considering their low numbers. In the past decades a number of authors have proposed different descriptive models to explain their relevance, highlighting factors such as an improvement on unit cohesion or high levels of aggressiveness, which made them lead the charges against the enemy. However, the lack of a quantitative framework does not allow to compare and test these working hypotheses. This paper suggests an innovative methodological approach to explore the problem, based on computer simulation. An Agent-Based Model of roman legions is used as a virtual laboratory, where different hypotheses are tested under varying scenarios. Results suggest that the resilience of formations to combat stress increase exponentially if they contain just a small percentage of homogeneously distributed warriors with higher psychological resistance. Additionally, the model also shows how the lethality of the entire formation is reinforced when this selected group is located at the first line of the formation, even if individually they are not more aggressive or skilled than the average. The interpretation of the simulated patterns in terms of Roman warfare suggest that the multiple roles of the centurions observed in the sources were not caused by changes in tactics or values, but can be strictly explained by an increase in their experience and overall combat performance. -

Gaius Valerius – a Roman Soldier

Gaius Valerius – A Roman Soldier Salvete! My name is Gaius Valerius and I’m a soldier in the 9th Legion here in Lindum, or Lincoln as you call it. I thought I’d tell you a little about life in the Roman army. Joining the army • First, you must be a Roman citizen – you can’t be a slave or a criminal either! The best age to join is 17-20, Training although I was 21. You mustn’t be After 4 months training you have to be married! able to: • Next you need to ask a family friend • march 27 miles in 5 hours, whilst to write a letter saying what a good carrying 60 pounds of equipment soldier you would be and (that’s the weight of a large dog!) have an interview. • fight with a sword and throw a • Then a doctor checks you spear are healthy. • use your shield to protect yourself • build a camp (dig a ditch, cut down trees, build a palisade and put up a tent) • bandage a wound Salve mum, Life here is good, I spend the I have great news – I’ve been mornings training and doing promoted to signifer. It means I chores, then after cena (our carry the legion’s standard into afternoon meal) I can relax battle. It’s a very important job and go to the baths, or visit the because I give signals to the tavern outside the fort. soldiers so they know what to My centurion, Hospes, is a do whilst we are marching. good leader and rarely needs to During battle the soldiers will punish the men with his vine group around the standard and I rod. -

Seven Centurions

Seven Centurions By Mark Mayberry 7/27/2014 Introduction In this lesson, we consider the seven centurions mentioned in Sacred Scripture, and the varied lessons they communicate. Thomas defines hekatontarchēs or hekatontarchos, derived from hekaton [a hundred] and archō [to rule, to begin], as “a centurion, a captain of one hundred men” [1543]. BDAG say it refers to “a Roman officer commanding about a hundred men (subordinate to a tribune), centurion, captain.” This word occurs 20x in the NT (Matt. 8:5, 8, 13; 27:54; Luke 7:2, 6; 23:47; Acts 10:1, 22; 21:32; 22:25, 26; 23:17, 23; 24:23; 27:1, 6, 11, 31, 43). Additionally, one other word should be considered. Thomas defines kenturiōn, of Latin origin, as “a centurion (a Roman army officer)” [2760]. BDAG say this Latin loanword refers to a “centurion (=ἑκατοντάρχης).” This word occurs 3x in the NT, and only in Mark’s account of the crucifixion (Mark 15:39, 44, 45). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia provides the following summary: A centurion was “The commander of a hundred men (a “century”), more or less, in a Roman legion. Matthew and Luke use the Greek word while Mark characteristically prefers the Latin form, since he seems to write primarily for Roman readers.” “The number of centurions in a legion was always sixty, but the number in the cohort or speíra varied. The ordinary duties of the centurion were to drill his men, to inspect their arms, food, and clothing, and to command them in the camp and in the field. -

Roman Military Medicine

Roman Military Medicine Roman Military Medicine: Survival in the Modern Wilderness By Valentine J. Belfiglio and Sylvia I. Sullivant Roman Military Medicine: Survival in the Modern Wilderness By Valentine J. Belfiglio and Sylvia I. Sullivant This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Valentine J. Belfiglio and Sylvia I. Sullivant All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3087-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3087-4 To Ellie and Brent. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations .................................................................................... ix Foreword ................................................................................................... xi Chapter I ..................................................................................................... 1 Introduction Chapter II .................................................................................................... 5 Sanitation in Ancient Roman Military Hospitals Chapter III ................................................................................................ 13 Control of Epidemics Chapter IV ............................................................................................... -

A CENTURION and HIS SLAVE. a Latin Epitaph from Western Anatolia in the Rijksmuseum Van Oudheden, Leiden

10003-07_Anatolica-33_04crc 16-04-2007 14:06 Pagina 129 Anatolica 33, 129-142. doi: 10.2143/ANA.32.0.2012551 © 2007 by Anatolica. All rights reserved. ANATOLICA XXXIII, 2007 A CENTURION AND HIS SLAVE. A Latin Epitaph from Western Anatolia in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden Julian Bennett1 Introduction Among the items displayed in the Greek and Roman Antiquities section of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, is a Latin epitaph that was bought in Smyrna (øzmir) in 1889 by a private collector and subsequently acquired on behalf of the museum by Conrad Leemans (Fig. 1).2 The epitaph is carved on a slab of marbleized limestone with a face measurement of 30 x 32 cm. and an overall thickness of 4 cm. except towards the top, where a cantilevered upper margin 5 cm high terminates in a flat vertical border that is 4.5 cm. thick. The serif lettering used for the text of the epitaph is competently and finely carved, demonstrating a familiarity with the Latin script (although a letter is missing from one word), with characters that vary slightly in height between 2.3-2.4. The text reads: Senilis · Q(uinti) · Atti · / Celeris · (centurionis) leg(ionis) · IIII · / Scyt<h>icae · servos [·] / vixit · ann(os) · XX In free paraphrase this may be translated as: ‘Senilis, the slave of Quintus Attius Celer, a centurion in the legio IIII Scythica: he lived 20 years’. A date for the epitaph in the period c. AD 50-100 is suggested by two items of chronological value: the inclusion in the text of Celer’s full tri nomina; and the lavish superscript tails supplied for the ‘Y’ in ‘Scyticae’ and the ‘X’ in ‘vixit’. -

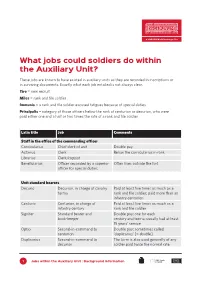

What Jobs Could Soldiers Do Within the Auxiliary Unit?

A UNESCO World Heritage Site What jobs could soldiers do within the Auxiliary Unit? These jobs are known to have existed in auxiliary units as they are recorded in inscriptions or in surviving documents. Exactly what each job entailed is not always clear. Tiro = new recruit Miles = rank and file soldier Immunis = a rank and file soldier excused fatigues because of special duties Principalis = category of those officers below the rank of centurion or decurion, who were paid either one and a half or two times the rate of a rank and file soldier Latin title Job Comments Staff in the office of the commanding officer Cornicularius Chief clerk of unit Double pay Actarius Clerk Below the cornicularius in rank Librarius Clerk/copyist Beneficiarius Officer seconded by a superior Often lives outside the fort officer for special duties Unit standard bearers Decurio Decurion, in charge of cavalry Paid at least five times as much as a turma rank and file soldier; paid more than an infantry centurion Centurio Centurion, in charge of Paid at least five times as much as a infantry century rank and file soldier Signifer Standard bearer and Double pay; one for each book-keeper century and turma; usually had at least 15 years’ service Optio Second-in-command to Double pay; sometimes called centurion ‘duplicarius’ [= double] Duplicarius Second-in-command to The term is also used generally of any decurion soldier paid twice the normal rate 1 Jobs within the Auxiliary Unit : Background information A UNESCO World Heritage Site Tesserarius Officer officer below the rank of Pay and a half; only in infantry. -

Maniple to Cohort: an Examination of Military Innovation and Reform in the Roman Republic

MANIPLE TO COHORT: AN EXAMINATION OF MILITARY INNOVATION AND REFORM IN THE ROMAN REPUBLIC A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE Military History by BENJAMIN J. NAGY, MAJOR, US ARMY B.S., University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho, 2003 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2014-01 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 13-06-2014 Master’s Thesis AUG 2013 – JUN 2014 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Maniple to Cohort: An Examination of Military Innovation and 5b. GRANT NUMBER Reform in the Roman Republic 5c. -

Troops and Commanders: Auxilia Externa Under the Roman Republic*

JONATHAN R.W. PRAG Troops and commanders: * auxilia externa under the Roman Republic I. Introduction During the last two centuries of the Roman Republic, the Roman state made use of troops from outside of Italy, i.e. from peoples not included in the formula togatorum, and who were not part of the socii ac nomen Latini. These soldiers can be classified under the semi-formal designation of auxilia externa, although the term is used with little regularity, and they are more usually described by our sources in diverse ways (typically by ethnic, e.g. ‘Aetolians’, and/or type of soldier, e.g. funditores); frequently their presence can only be inferred or guessed at.1 The evidence exists to suggest that the use of these troops was extensive, but their existence is rarely acknowledged in modern discussions of the Roman army, and there is to date no systematic collection or analysis of the material as a whole.2 * This paper derives from ongoing work on a monograph provisionally entitled Non-Italian Manpower: auxilia externa under the Roman Republic, with support from the AHRC; see already J.R.W. Prag, Auxilia and gymnasia: a Sicilian model of Roman Republican Imperialism, «JRS» XCVII (2007), 68-100. I am grateful to Prof.ssa R. Marino for the invitation to participate at the conference at which a version of this paper was first presented, and to the department of ancient history at Palermo as a whole, and Davide Salvo in particular, for their generous hospitality. 1 The key texts are: Fest. 16 L: Auxiliares dicuntur in bello socii Romanorum exterarum nationum ...; Varro ling. -

Loyalty and the Sacramentum in the Roman Republican Army Loyalty and the Sacramentum

LOYALTY AND THE SACRAMENTUM IN THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN ARMY LOYALTY AND THE SACRAMENTUM IN THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN ARMY By ALEXANDRA HOLBROOK, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Alexandra Holbrook, August 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) McMaster University (Classics) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Loyalty and the Sacramentum in the Roman Republican Army AUTHOR: Alexandra Holbrook, B.A. (University of Guelph) SUPERVISOR: Professor E.W. Haley NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 100 ii ABSTRACT Despite the large corpus of scholarly writing about the Roman army, the military oath, or sacramentum, of the late Republican legions has not been studied at length. Since the fall of the Republic was rooted in the struggle for political and military dominance by individuals, the loyalty of the legions to these commanders is of utmost historical importance. The first chapter focuses on the geographic and social origins of the soldiers of the late Republic, which have been studied extensively and provide a background from which to assess the composition of the army. As well, the conditions of service for this period are significant factors affecting the obedience of soldiers to their commanders, and the second chapter of this thesis places particular emphasis on problems of length of service, pay, booty and plunder, and military discipline. This framework of conditions and characteristics supports the analysis of the sacramentum itself in the third chapter. The textual evidence for the oath, both direct and indirect, are gathered for comparative purposes and applied to historical anecdotes of loyal and disloyal behaviour for the period in question.