Chapter 2: Participatory Planning and Inclusive Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Regional Political Parties and Formation of the Coalition Governments in Meghalaya Mr

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies (IJHSSS) A Peer-Reviewed Bi-monthly Bi-lingual Research Journal ISSN: 2349-6959 (Online), ISSN: 2349-6711 (Print) Volume-III, Issue-V, March 2017, Page No. 206-218 Published by Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.ijhsss.com Role of Regional Political Parties and Formation of the Coalition Governments in Meghalaya Mr. Antarwell Warjri Ph.D Research Scholar, Department of Political Science; William Carey University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India Abstract Regional unevenness is one of the main reasons responsible for the emergence of the regional political parties in the state of Meghalaya. Other responsible factors that led to the emergence of the regional political parties in the state were the presence of multi-cultures, multi-languages, factionalism, personality cult, and demand for Autonomy. Another important factor was that of the negligence of the national parties in the development of the region and the ever-increasing centralized tendency has become the primary reasons for the emergence of regional political parties in the state. This investigation tries to draw out reasons on the evolution of regional political parties in Meghalaya The study had examined and evaluated the emergence of regional political parties, programmes, role and their contribution to the formation of Coalition Government in Meghalaya during the period from 1972-2013. The idea of Coalition is an act of uniting into one body or to grow together. Meghalaya was inevitable from the detrimental effect of Coalition Government because no single political party is able to secure a working majority in the house on account of the presence of the multi party system. -

Request for Proposal

BID DOCUMENT NO.MIS/NeGP/CSC/08 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL FOR SELECTION OF SERVICE CENTRE AGENCIES TO SET UP, OPERATE AND MANAGE TWO HUNDRED TWENTY FIVE (225) COMMON SERVICES CENTERS IN THE STATE OF MEGHALAYA VOLUME 3: SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION TO BIDDERS Date: _________________ ISSUED BY MEGHALAYA IT SOCIETY NIC BUILDING, SECRETARIAT HALL SHILLONG-793001 On Behalf of INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA Content 1. List of Websites of Megahalya 2. List of BSNL rural exchange 3. Ac Neilsen Study on Meghalaya (including Annexure-I & Annexure-II) List of BSNL Rural Exchanges Annexure -3 Exchange details Sl.No Circle SSA SDCA SDCC No. of Name Type Cap Dels villages covered 1 NE-I Meghalaya Cherrapunji Cherrapunji Cherrapunji MBMXR 744 513 2 NE-I Meghalaya Cherrapunji Cherrapunji Laitryngew ANRAX 248 59 3 NE-I Meghalaya Dawki Dawki Dawki SBM 360 356 4 NE-I Meghalaya Dawki Dawki Amlaren 256P 152 66 5 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Phulbari SBM 1000 815 6 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Rajabala ANRAX 312 306 7 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Selsella 256P 152 92 8 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Holidayganj 256P 152 130 9 NE-I Meghalaya Phulbari Phulbari Tikkrikilla ANRAX 320 318 10 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai 8th Mile ANRAX 248 110 11 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Kyndongtuber ANRAX 152 89 12 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Nartiang ANRAX 152 92 13 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Raliang MBMXR 500 234 14 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Shanpung ANRAX 248 236 15 NE-I Meghalaya Jowai Jowai Ummulong MBMXR 500 345 16 NE-I Meghalaya Khileiriate -

Urban Development

MMEGHALAYAEGHALAYA SSTATETATE DEVELOPMENTDEVELOPMENT RREPORTEPORT CHAPTER VIII URBAN DEVELOPMENT 8.1. Introducti on Urbanizati on in Meghalaya has maintained a steady growth. As per 2001 Census, the state has only 19.58% urban populati on, which is much lower than the nati onal average of 28%. Majority of people of the State conti nue to live in the rural areas and the same has also been highlighted in the previous chapter. As the urban scenario is a refl ecti on of the level of industrializati on, commercializati on, increase in producti vity, employment generati on, other infrastructure development of any state, this clearly refl ects that the economic development in the state as a whole has been rather poor. Though urbanizati on poses many challenges to the city dwellers and administrators, there is no denying the fact that the process of urbanizati on not only brings economic prosperity but also sets the way for a bett er quality of life. Urban areas are the nerve centres of growth and development and are important to their regions in more than one way. The current secti on presents an overview of the urban scenario of the state. 88.2..2. UUrbanrban sseett llementement andand iitsts ggrowthrowth iinn tthehe sstatetate Presently the State has 16 (sixteen) urban centres, predominant being the Shillong Urban Agglomerati on (UA). The Shillong Urban Agglomerati on comprises of 7(seven) towns viz. Shillong Municipality, Shillong Cantonment and fi ve census towns of Mawlai, Nongthymmai, Pynthorumkhrah, Madanrti ng and Nongmynsong with the administrati on vested in a Municipal Board and a Cantonment Board in case of Shillong municipal and Shillong cantonment areas and Town Dorbars or local traditi onal Dorbars in case of the other towns of the agglomerati on. -

Addendum Nongtalang.Pdf

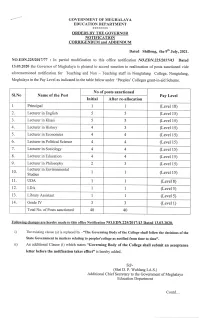

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA EDUCATION DEPARTMENT !krl***rr** ORDERS BY GOVERNOR NOTIFICATION CORRIGENDUM and ADDENDUM Dated Shillong, the 9th Julyr2L2l. NO.EDN.225|20L7l77 : In partial modification to this office notification NO.EDN.225/2017/43 Dated 13.03.2020 the Governor of Meghalaya is pleased to accord sanction to reallocation of posts sanctioned vide aforementioned notification for Teaching and Non - Teaching staff in Nongtalang College, Nongtalang, Meghalaya in the Pay Level as indicated in the table below under 'Peoples' Colleges grant-in-aid Scheme. No of posts sanctioned Sl.No Name of the Post Pay Level Initial After re-allocation 1 Principal I 1 (Level l8) 2. Lecturer in English 5 5 (Level l5) 3 Lecturer in Khasi 5 5 (Level 15) 4 Lecturer in History 4 3 (Level 15) 5 Lecturer in Economics 4 4 (Level 15) 6 Lecturer in Political Science 4 4 (Level l5) 7 Lecturer in Sociology 4 4 (Level l5) 8 Lecturer in Education 4 4 (Level 15) 9 Lecturer in Philosophy 2 J (Level 15) Lecturer in Environmental 10 I 1 (Level 15) Studies 11 UDA I 1 (Level 8) 12. LDA 1 1 (Level 5) 13 Library Assistant 1 I (Level 5) t4 Grade IV J J (Level l) Total No. of Posts sanctioned 40 40 Followins chanees are herebv made to this office Notification NO.EDN.225I2017143 Dated 13.03.2020. i) The existing clause (s) is replaced by -"The Governing Body of the Cotlege shall follow the decisions of the State Government in matters relating to peoples'college as notified from time to time,'. -

Ri-Bhoi and West Khasi Districts

क� द्र�यू�म भ जल बोड셍 जल संसाधन, नद� �वकास और गंगा संर�ण मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING REPORT Parts of Ri-Bhoi & West Khasi Hills Districts, Meghalaya उ�र� पूव� �ेत्र, गुवाहाट� North Eastern Region, Guwahati AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT IN PARTS OF RI-BHOI & WEST KHASI HILLS DISTRICTS, MEGHALAYA CONTENTS Page No. 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. MAJOR GROUNDWATER ISSUES IN THE AREA 1 3. MANIFESTATION AND REASONS OF ISSUES 1 - 2 4. AQUIFER GEOMETRY AND CHARACTERIZATION 2 - 3 5. AQUIFER MANAGEMENT PLAN 3 – 4 MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES MANAGEMENT PLAN ANNEXURE9 Maps 5 - 19 Map 1 Administrative map Map 2 Soil map Map 3 Isohyet map Map 4 Drainage map Map 5 Geological map 1 Map 6 Depth to water level map (Pre-monsoon), Shallow aquifer Map 7 Depth to water level map (Post-monsoon), Shallow aquifer Map 8 Location of exploratory boreholes Map 9 Bore hole logs showing disposition of aquifer Map 10 Distribution of conductivity in ground water Map 11 Distribution of iron in ground water Map 12 Distribution of pH in ground water Map 13 Location of VES point Map 14 Location of springs Map 15 3 D Aquifer disposition Table 20 - 61 Table 1: Litholog Table 2: Aquifer Parameters Table 3: Aquifer wise water quality data Table 10 Water Level Monitoring Data Table 11 Rainfall data Table 12 VES/TEM Data FIELD PHOTOGRAPH 62 - 66 2 AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT IN PARTS OF RI-BHOI & WEST KHASI HILLS DISTRICTS, MEGHALAYA 1. -

Meghalaya S.No

Meghalaya S.No. District Name of the Establishment Address Major Activity Description Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Activit ship yment y Code Code Class Interva l 107C.M.C.L STAR CEMENT 17 LUMSHNONG, JAINTIA FMANUFACTURE OF 06 325 4 >=500 INDUSTRIES LTD HILLS 793200 CEMENT 207HILLS CEMENTS 11 MYNKRE, JAINTIA MANUFACTURE OF 06 239 4 >=500 COMPANY INDUSTRIES HILLS 793200 CEMENT LIMITED 307AMRIT CEMENT 17 UMLAPER JAINTIA -MANUFACTURE OF 06 325 4 >=500 INDUSTRIES LTD HILLS 793200 CEMENT 407MCL TOPCEM CEMENT 99 THANGSKAI JAINTIA MANUFACTURE OF 06 239 4 >=500 INDUSTRIES LTD HILLS 793200 CEMENT 506RANGER SECURITY & 74(1) MAWLAI EMPLOYMENT SERVICE 19 781 2 >=500 SERVICE ORGANISATION, MAWAPKHAW, SHILLONG,EKH,MEGHALA YA 793008 606MEECL 4 ELECTRICITY SUPPLIER 07 351 4 >=500 LUMJINGSHAI,POLO,SHILL ONG,EAST LAWMALI KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793001 706MEGHALAYA ENERGY ELECTRICITY SUPPLY 07 351 4 >=500 CORPORATION LTD. POLO,LUMJINGSHAI,SHILL ONG,EAST KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793001 806CIVIL HOSPITAL 43 BARIK,EAST KHASI HOSPITAL 21 861 1 >=500 SHILLONG HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793004 906S.S. NET COM 78(1) CLEVE COLONY, INFORMATION AND 15 582 2 200-499 SHILLONG CLEVE COMMUNICATION COLONY EAST KHASI HILLS 793001 10 06 MCCL OFFICE SOHSHIRA 38 BHOLAGANJ C&RD MANUFACTURE OF 06 239 4 200-499 MAWMLUH SHELLA BLOCK EAST KHASI HI CEMENT MAWMLUH LLS DISTRICT MEGHALAYA 793108 11 06 MCCL SALE OFFICE MAWMLUH 793108 SALE OFFICE MCCL 11 466 4 200-499 12 06 DR H.GORDON ROBERTS 91 JAIAW HOSPITAL HEALTH 21 861 2 200-499 HOSPITAL PDENG,SHILLONG,EAST SERVICES KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793002 13 06 GANESH DAS 47 SHILLONG,EAST KHASI RESIDENTIAL CARE 21 861 1 200-499 HOSPITAL,LAWMALI HILLS MEGHALAYA ACTIVITIES FORWOMEN 793001 AND CHILDREN 14 06 BETHANY HOSPITAL 22(3) NONGRIM HOSPITAL 21 861 2 200-499 HILLS,SHILLONG,EAST KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793003 15 06 GENERAL POST OFFICE 12 KACHERI ROAD, POSTAL SERVICES 13 531 1 200-499 SHILLONG KACHERI ROAD EAST KHASI HILLS 793001 16 06 EMERGENCY 19(1) AMBULANCE SERVICES. -

Sanction No.LJ(A)67/2013/22

GOVERNMENT OF !\1EGHALAYA LAW (A) DEPARTMENT. No. LJ (A) 6712013/22 Dated Shillong, the nIh May, 2015. From : Shri L.M. Sangma. Secretary [Q the Government ofMeghaJaya, Law Depanment. To. The First Class Judicial Magistrate, Mairang Civil Sub-Division West Khasi Hills, Distric'f,,Mairang . •• Subject: - Crealiqn of J(olle) post ofdriver for tile Office o/lst Class Judicial Magistrate, West Khasi Hills Dis/riel, Mairallg S ub-liivisioll. Sir. I am directed to convey the sanction of the Governor of Meghalaya to the creation of 1 (o ne) post of driver for the Office of lit Class Judicial Magistmte, West Khasi Hills District, Mairang Civil Sub-division in the scale ofJlay of~ 7700-190·9030-EB-2S0-11280-340 15020/· P.M. plus other allowances as admissible under the Rule with effect from the date of entertainment till 29.02.20 16. The expendilUre is debitable to the Head of Account "20l4·Administration of Justice -108-Criminal Courts -{03)·establishment of Chief Judicial Magistrate and other Judicial Magistnlte etc .• Non - Plan" in the budget for the year 2015-2016 . • This sanction issues with the concurrence of Finance EC.IJ Department vide their !.'D Fin (EC.1I).7 I 911 4 dt. 28.03.2015. Yours faithfully. ~ Secretaryto the Government of Meghalaya. Law Department. 111 Memo No. U (A) 67f2013f22-A Dated Shillong, the 13 May. 2015. Copy forwarded to: • 1. The Registrar General High Court of Meghalaya 2. District & Sessions Judge, Nongstoin. 3. Finance (EC.U) Department (consulted liD). 4. Personnel AR (8) Department. 5. ~asury Officer Mairang, West Khasi Hills District. -

Notification

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA t LAW (B) DEPARTMENT ***** NOTIFICATION Dated Shillong, the 23 rd March, 2020. No. LJ(B)S3/93/S00 - In exercise of the powers conferred by Section 2 of the Epidemic Diseases Act,1897, the Governor of Meghalaya is pleased to confer powers of Executive Magistrates on the following Officers in the interest of Public Services within Mairang (Civil) Sub Division, West Khasi Hills District with immediate effect and until further orders - 51. Name of the Officer Designation I No. 1 Shri L.Shabong Executive Engineer, PWD (Roads), Mairang 2 Shri . T.T,Khyllait AStt.Executive Engineer,PWD (Roads),Mairang 3 Shri M .L.Kynta Sr. Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Officer,Manai 4 Shri. L.Dhar Executive Engir:leer, PHE (Rws),Mairang 5 Shri. B.Dohtdong Asstt. Employment Exchange Officer, Mairang 6 Shri.S. Kharsati Sub-Divisional Agriculture Officer. 7 Shri T.Marbaniang Asst.EE. (PH E) Rws, Sub-Divisional Officer, Mairang 8 Shri. D.Tiewla Horticulture Development Officer ,Office of SDAO.Mairang 9 Shri. R.Kharshilot Child Development Project Officer (ICDS)Mawthadraishan 10 Shri. S.J.Kharlor Range Officer of Soil & Water Conservation Range,Mairang 11 Shri. T.Wanshong Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Officer, Mairang. 12 Shri S. KHarpran Animal Husbandary & Veterinary Officer, Mairang. 13 Shri S. Puwein Asstt. Executive Engineer, PWD Rds, Mairang. 14 Shri K. Rymbai' Asstt. Executive Engineer, PWD Rds, Nongkhlaw 15 Shri D. Lamare Asstt. Executive Enginee'r, Rds, Markasa 16 Smti B. Kharsyntiew Agriculture Development Officer, Office of SDAO, Mairang. 17 Shri S. Tham Sub-Divisional A&H Veterinary Officer, Mairang. 18 Shri A.B. -

1. Name of Public Authority: Directorate of Sericulture and Weaving, Meghalaya, Shillong

CHAPTER -8 (Manual 7) Name, Designation, Particulars of Public Information Officers: 1. Name of Public Authority: Directorate of Sericulture and Weaving, Meghalaya, Shillong. Appellate Authority Public Authority Name Designation Phone No. Fax Email Address Directorate of Shri. B. Director, 2223279 0364- Dirswgovt_me Directorate of Sericulture and Sericulture and Ch. Sericulture 2223279 [email protected] Weaving, Lower Lachumiere, Weaving Hajong and Weaving om Nokrek building, Meghalaya, Shillong- 793001 DISTRICT HEADQUARTER East Khasi Hills -do- -do- Ri-Bhoi District -do- -do- Jaintia Hills -do- -do- West Khasi Hills -do- -do- West Garo Hills Smt. L. Jt. Director, Dkhar Sericulture and Weaving, Tura East Garo Hills -do- -do- South Garo Hills -do- -do- SUB-DIVISION Public Authority Name Designation Phone No. Fax Email Address Sohra Sub Division Shri. B. Director, Ch. Sericulture Hajong and Weaving Mairang Sub Division -do- -do- Amlarem Sub -do- -do- Division Khliehriat Sub -do- -do- Division Resubelpara Sub Smt. L. Jt. Director, Division Dkhar Sericulture and Weaving, Tura Ampati Sub Division -do- -do- Dadengri Sub -do- -do- Division PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS Public Authority Name Designation Phone No. Fax Email Address Directorate of Smti.B. Lyngdoh DDS 2223279 0364- dirswgovt_megh Directorate of Sericulture and Sericulture and Weaving 2223279 @hotmail.com Weaving, Lower Lachumiere, Nokreh building, Meghalaya, Shillong- 793001 DISTRICT HEADQUARTER East Khasi Hills Shri. D.D. Medhi DSO, Shillong - - Smti. M.R. Leewait ZOW, Shillong Ri-Bhoi District Shri.F. Kharkongor DSO, Nongpoh - serinongpoh@ Smti. D.P. Tariang DHO, Nongpoh gmail.com Jaintia Hills Smti. A. Passah DSO, Jowai 953632223 - Smti. D. Lyngdoh DHO, Jowai 804 West Khasi Hills Shri. -

West Khasi Hills District, Meghalaya

Technical Report Series: D No: GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET WEST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT, MEGHALAYA North Eastern Region Guwahati September, 2013 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET WEST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT, MEGHALAYA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE S.No. ITEMS STATISTICS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (sq. km.) 5,247 ii) Administrative Divisions 6 a) Mawshynrut Blocks b) Nongstoin c) Mairang d) Ranikor e) Mawkrywat f) Mawthadraishan Number of Villages 943 Sub-divisions 3 Towns 2 iii) Population (as per provisional 2011 census) 3,85,601 iv) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 3485 Source: Dept. of Agriculture, GOM 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Denudational low hills and highly dissected plateau in the south with minor valleys. The district is hilly with deep gorges and narrow valleys. Major Drainages Kynshi,Wahkri, Rilang, Rwiang, Umngi Rivers 3. LAND USE (Sq Km) (in 2010-2011) a) Forest area 2065.30 b) Net area sown 301.22 c)Gross Cropped area 366.89 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Red Gravelly Soil and Red Loamy Soil Source: Dept. of Agriculture, GOM 5. AREA UNDER PRINICIPAL CROPS (as Rice, Maize, Millets, Oilseeds and pulses. on 2010-11, in sq Km) Kharif: Rice:77.63, Maize:42.55 Rabi : Rice:0.52, Millets:2.32, Pulses:0.33, Oilseeds:0.56, Sugarcane:0.06 & Tobacco:0.32 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES a. Surface water (sq km) 10 Sq.Km. Mainly by surface water. b. Ground water (sq km) Negligible. 7. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL a. Archaean Gneissic Complex FORMATIONS b. Shillong Group of rocks Granitic, Gneissic and schistose rocks with sedimentary rocks like sandstone and limestone. -

46166-001: Supporting Human Capital Development in Meghalaya

Indigenous Peoples Plan January 2013 IND: Supporting Human Capital Development in Meghalaya This indigenous peoples plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADC – Autonomous District Council DPCU – District Project Coordination Unit FGD – focus group discussion GOM – Government of Meghalaya HS – higher secondary IPP – Indigenous Peoples Plan JFPR – Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction M&E – monitoring and evaluation MSSDS – Meghalaya State Skill Development Society NGO – nongovernment organization PIU – Project Implementation Unit PMU – Project Management Unit RMSA – Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan SCF – Skills Challenge Fund SMC – school management committee SS – secondary ST – scheduled tribe TA – technical assistance TLPC – The Living Picture Company TVET – technical and vocational education and training CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 B. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT 2 a. Background 2 b. Project – Brief Description 3 c. Overview of the Project Area 3 C. SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT 4 a. Legal and Institutional Framework for Tribal Administration and Development 4 b. Baseline Information 6 D. INFORMATION DISCLOSURE, CONSULTATION, AND PARTICIPATION 6 a. Meaningful Consultations – Approach and Methodology 6 b. Key Findings 7 c. Incorporating Tribal and Gender Concerns into Project Design – The Proposed Plan 8 d. -

List of Public Works Divisions with Code

List of Works Divisions Sl Name of Works and other Divisions Code .No. No. 1 The C.E., P.W.D (Roads), Shillong Division 14 2 The Additional C.E., P.W.D (Roads),Western Zone, Tura 15 Division 3 The S.E., P.W.D(Roads), Eastern Circle, Shillong Division 16 4 The S.E., P.W.D (Roads), Western Circle,Nongstoin Division 17 5 The S.E., P.W.D. (Roads), N.H. Shillong Circle, Shillong 18 Division 6 The S.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Tura Circle, Tura Division 19 7 The S.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Williamnagar Division 20 8 The S.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Jowai Circle 21 9 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Mechanical Division, Shillong 22 10 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Mechanical Division, Tura 23 11 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Mechanical Division, Jowai 24 12 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Shillong South Division 25 13 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Shillong Central Division 26 14 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Nongpoh Division, Nongpoh 27 15 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Mairang Division 28 16 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Mawsynram Division, Mawsynram 29 17 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), Mawkyrwat Division 30 18 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), National Highway Division, 31 Shillong 19 The E.E., P.W.D. (Roads), National Highway Bye-Pass 32 Division 20 The E.E, P.W.D. (Roads), Nongstoin Division, Nongstoin 33 21 The E.E., P.W.D.