MEMORANDUM to the GOVERNMENT of INDIA on the UNFCCC’S 15Th CONFERENCE of the PARTIES at COPENHAGEN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

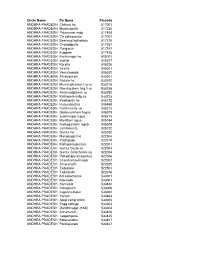

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Place Based Incentive.Pdf

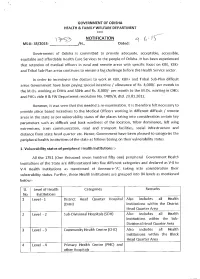

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT *** NOTIFICATION )c)5. 9 6 35/2015- /H., Dated: Government of Odisha is committed to provide adequate, acceptable, accessible, equitable and affordable Health Care Services to the people of Odisha. It has been experienced that retention of medical officers in rural and remote areas with specific focus on KBK, KBK+ and Tribal Sub-Plan areas continues to remain a big challenge before the Health Service sector. In order to incentivise the doctors to work in KBK, KBK+ and Tribal Sub-Plan difficult areas Government have been paying special incentive / allowance of Rs. 4,000/- per month to the M.Os. working at DHHs and SDHs and Rs. 8,000/- per month to the M.Os. working in CHCs and PHCs vide H & FW Department resolution No. 1489/H, dtd. 20.01.2012. However, it was seen that this needed a re-examination. It is therefore felt necessary to provide place based incentives to the Medical Officers working in different difficult / remote areas in the state as per vulnerability status of the places taking into consideration certain key parameters such as difficult and back wardness of the location, tribal dominance, left wing extremisms, train communication, road and transport facilities, social infrastructure and distance from state head quarter etc. Hence, Government have been pleased to categories the peripheral health institutions of the state as follows basing on their vulnerability status. 1. Vulnerability status of peripheral Health Institutions :- All the 1751 (One thousand seven hundred fifty one) peripheral Government Health Institutions of the State are differentiated into five different categories and declared as V-0 to V-4 Health Institutions as mentioned at Annexure-'A', taking into consideration their vulnerability status. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

HIGHSCHOOLS in GANJAM DISTRICT, ODISHA, INDIA Block Type of High Sl

-1- HIGHSCHOOLS IN GANJAM DISTRICT, ODISHA, INDIA Block Type of High Sl. Block G.P. Concerned Village Name of the School Sl. School 1 1 Aska Aska NAC Aska Govt. Girl's High School, Aska Govt. 2 2 Aska Aska NAC Aska Harihar High School, Aska Govt. 3 3 Aska Aska NAC Aska Tech High School, Aska Govt. 4 4 Aska Munigadi G. P. Munigadi U. G. Govt. High School, Munigadi Govt. U.G. 5 5 Aska Mangalpur G. P. Mangalpur Govt. U. G. High School, Mangalpur Govt. U.G. 6 6 Aska Khaira G. P. Babanpur C. S. High School, Babanpur New Govt. 7 7 Aska Debabhumi G. P. Debabhumi G. P. High School, Debabhumi New Govt. 8 8 Aska Gunthapada G. P. Gunthapada Jagadalpur High School, Gunthapada New Govt. 9 9 Aska Jayapur G. P. Jayapur Jayapur High School, Jayapur New Govt. 10 10 Aska Bangarada G. P. Khukundia K & B High School, Khukundia New Govt. 11 11 Aska Nimina G. P. Nimina K. C. Girl's High School, Nimina New Govt. 12 12 Aska Kendupadar G. P. Kendupadar Pragati Bidyalaya, Kendupadar New Govt. 13 13 Aska Baragam Baragam Govt. U.G. High School, Baragam NUG 14 14 Aska Rishipur G.P. Rishipur Govt. U.G. High School, Rishipur NUG 15 15 Aska Aska NAC Aska N. A. C. High School, Aska ULB 16 16 Aska Badakhalli G. P. Badakhalli S. L. N. High School, Badakhalli Aided 17 17 Aska Balisira G. P. Balisira Sidheswar High School, Balisira Aided 18 18 Aska GangapurG. P. K.Ch. Palli Sudarsan High School, K.Ch. -

Ganjam District

CHATRAPUR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 CHATRAPUR 72 2 GANJAM 10 3 RAMBHA 106 4 CHAMAKHANDI 27 5 KHALLIKOTE 120 6 MARINE 02 TOTAL 337 PURUSOTAMPUR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 PURUSOTAMPUR 56 2 KODALA 75 3 POLOSARA 39 4 KABISURYANAGAR 103 TOTAL 273 ASKA SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 ASKA 606 2 HINJILI 110 3 SHERAGAD A 39 4 PATTAPUR 75 5 DHARAKOTE 109 6 BADAGADA 107 7 SORODA 84 TOTAL 1130 BHANJANAGAR SUB-DIVISION S.I NO POLICE STATION NBWs PENDING FIGURE 1 BHANJANAGAR 245 2 BUGUDA 64 3 GANGAPUR 57 4 J.N.PRASAD 37 5 TARASINGH 66 TOTAL 469 NAME OF SUB-DIVISION TOTAL CHATRAPUR SUB-DIVISION 337 PURUSOTAMPUR SUB-DIVISION 273 ASKA SUB-DIVISION 1130 BHANJANAGAR SUB-DIVISION 469 TOTAL 2209 GANJAM PS Sl No. NBW REF NAME THE FATHERS NAME ADDRESS THE CASE REF WARRANTEE WARRANTEE 1. ADDL SESSION Ramuda Krishna Rao S/O- Roga Rao vill- Malada PS/Dist Ganjam ST-75/13 U/S- 147/148/149/307 JUDGE CTR Ganjam . /323/324/337/294/506/34 IPC . 2. 2nd Addl Dist and Bhalu @ Susanta S/O- Bhakari Gouda vill Maheswar Colony SC- 42/07(A) Session Judge , Gouda PS/Dist Ganjam SC—119/05 Chatrapur 3. ASST SESSION Shyam Sundar Behera S/O- Balaram Behera vill- Kalyamar PS/Dist SC-6/96(3) U/S-147/148/294/307/ JUDGE CHATRAPUR @Babula Ganjam . 506/and 7 crl Amendment Act 4. S.D.J. -

ODISHA:CUTTACK NOTIFICATION No

OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION :ODISHA:CUTTACK NOTIFICATION No:-458(syllabus)/ Date19.07.2017 In pursuance of the Notification No-19724/SME, Dated-28.09.2016 of the Govt. of Odisha, School & Mass Education Deptt. & Letter No-1038/Plg, Dated-19.06.2017 of the State Project Director, OMSM/RMSA, the Vocational Education Course under RMSA at Secondary School Level in Trades i.e. 1.IT & ITES, 2.Travel & Tourism & 3.Retail will continue as such in Class-IX for the Academic session-2017-18 and 4.BFS (In place of B.F.S.I) , 5.Beauty & Wellness and 6. Health Care will be introduced newly in Class-IX(Level- I ) for the Academic Session- 2017-18 as compulsory subject in the following 208(old) & 106(new) selected Schools (Subject mentioned against each).The above subjects shall be the alternative of the existing 3rd language subjects . The students may Opt. either one of the Third Languages or Vocational subject as per their choice. The period of distribution shall be as that of Third Language Subjects i.e. 04 period per week so as to complete 200 hours of course of Level-I . The course curriculum shall be at par with the curriculum offered by PSSCIVE, Bhopal . List of 314 schools (208 + 106) approved under Vocational Education (2017-18) under RMSA . 208 (Old Schools) Sl. Name of the Approval Name of Schools UDISE Code Trade 1 Trade 2 No. District Phase PANCHAGARH BIJAY K. HS, 1 ANGUL 21150303103 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism BANARPAL 2 ANGUL CHHENDIPADA High School 21150405104 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 3 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR High School 21150606501 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism MAHENDRA High School, 4 ANGUL 21151001201 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism ATHAMALLIK 5 ANGUL MAHATAB High School 21150718201 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 6 ANGUL PABITRA MOHAN High School 21150516502 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 7 ANGUL JUBARAJ High School 21151101303 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 8 ANGUL Anugul High School 21150902201 Phase I IT/ITeS 9 BALANGIR GOVT. -

HOME (SPECIAL SECTION) DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION the 28Th March, 2019

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 629 CUTTACK, FRIDAY, MARCH 29, 2019/CHAITRA 8, 1941 HOME (SPECIAL SECTION) DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 28th March, 2019 No.838/C.— In continuation of this Department Notification No. 729/C., dated the 19th March, 2019 and in pursuance of powers conferred by Section-21 of Cr.P.C.1973 (Act.2 of 1974), the State Government do hereby appoint 39 (Thirty-nine) Officers as per the list annexed as Special Executive Magistrate in the District of Ganjam for smooth conduct of Simultaneous General Election, 2019 in Ganjam District area till completion of the Simultaneous General Election, 2019 in Ganjam District. By Order of the Governor P.C. PRADHAN Additional Secretary to Government 2 ANNEXURE LIST OF OFFICIALS GANJAM DISTRICT Sl. Name of the Officer & Office address Mobile No. No. Designation 1 Anil Kumar Behera, AAO, Asst. Agriculture Office, 8908586064 Dharakote 2 Debandra Kumar Sahu, ORS Dharakote Tahasil 9437775208 3 Biswa Ranjan Rout, AAO, Asst. Agriculture Office, 8895647213 Sankhemundi 9861335471 4 Ajit Kumar Mahapatra, AAO, Asst. Agriculture Office, 9438562103 Kukudakhandi 5 Kunja Bihari Dash,AFO, Asst. Fishery Office, 9090225390 Konisi 6 Sanjaya Kumar Samantaroy, Konisi Tahasil 6370413060 addl. Tahasildar, 7 Rakesh Nahak, Addl. Chatrapur Tahasil 9439459075 Tahasildar, 8 Gopal Krushna Adhikari, Berhampur Tahasil 9437204416 ORS. 9 Ajaya Nayak, AAO, Asst. Agriculture office 9090225390 Konisi 10 Padarbinda Sahu, AAO Asst. Agriculture Office 9439277439 Digapahandi 9853259740 11 Rajesh Kumar Behera, Office of the Asst. Soil 8093497355 ASCO, Conservation Office, Berhampur 12 Suvendu Ku. Panigrahy, Asst. Horticulture 9437086436 AHO, Office, Chikiti 9078074747 13 Basudev Bisoyi, AAO, Asst. Agriculture Office, 9437127448 Patrapur 14 Rabindra Kumar Mishra, Patrapur Tahasil 7326925432 addl .Tahasildar, 15 Siba Prasad Swain, ARCS, Asst. -

District Statistical Hand Book, Ganjam, 2018

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK GANJAM 2018 DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS, ODISHA ARTHANITI ‘O’ PARISANKHYAN BHAWAN HEADS OF DEPARTMENT CAMPUS, BHUBANESWAR PIN-751001 Email : [email protected]/[email protected] Website : desorissa.nic.in [Price : Rs.25.00] ସଙ୍କର୍ଷଣ ସାହୁ, ଭା.ପ.ସେ ଅର୍ଥନୀତି ଓ ପରିସଂ孍ୟାନ ଭବନ ନିସଦେଶକ Arthaniti ‘O’ Parisankhyan Bhawan ଅର୍େନୀତି ଓ ପରିେଂଖ୍ୟାନ HOD Campus, Unit-V Sankarsana Sahoo, ISS Bhubaneswar -751005, Odisha Director Phone : 0674 -2391295 Economics & Statistics e-mail : [email protected] Foreword I am very glad to know that the Publication Division of Directorate of Economics & Statistics (DES) has brought out District Statistical Hand Book-2018. This book contains key statistical data on various socio-economic aspects of the District and will help as a reference book for the Policy Planners, Administrators, Researchers and Academicians. The present issue has been enriched with inclusions like various health programmes, activities of the SHGs, programmes under ICDS and employment generated under MGNREGS in different blocks of the District. I would like to express my thanks to Dr. Bijaya Bhusan Nanda, Joint Director, DE&S, Bhubaneswar for his valuable inputs and express my thanks to the officers and staff of Publication Division of DES for their efforts in bringing out this publication. I also express my thanks to the Deputy Director (P&S) and his staff of DPMU, Ganjam for their tireless efforts in compilation of this valuable Hand Book for the District. Bhubaneswar (S. Sahoo) May, 2020 Dr. Bijaya Bhusan Nanda, O.S. & E.S.(I) Joint Director Directorate of Economics & Statistics Odisha, Bhubaneswar Preface The District Statistical Hand Book, Ganjam’ 2018 is a step forward for evidence based planning with compilation of sub-district level information. -

Provisional Common Merit List of Basic Bsc Nursing Female Candidates for the Academic Session 2018-19

PROVISIONAL COMMON MERIT LIST OF BASIC BSC NURSING FEMALE CANDIDATES FOR THE ACADEMIC SESSION 2018-19 ExS TotalP Fifth Total Fifth Eng GC TotalM Secur Perce Eng Eng ervi Index Date Of ercent Percen Phy Che Bio Mark FullMar Perce Carrea Secur Comm H PH SL. NO Name & Address Age ark10 ed 10 ntage Total Percen SC ST ce PH Sex No Birth GCH age 10 tage10 Mark Mark Mark Secure k ntage r Mark ed onRank Ran Rank class class Mark Mark tage Ran Category class Class d Mark Mark k EXSERVICE k TULASI MISHRA C/O: JUGALKISHORE MISHRA AT: LAIDA 18-Feb-00 18Yrs10Mon, 1 1516 F UR 10.00 9.40 89.30 44.65 92.00 88.00 90.00 270.00 300.00 90.00 45.00 89.65 100.00 87.00 87.00 1 PO:LAIDA 12:00:00 AM 13days DIST:SAMBALPUR PIN:768214 ODISHA MOB.NO:9937944954,7 377361241 NAZNEEN FIRDOUS C/O: SK. RAMJAN AT: KHANDIANGA,NEAR 10-Dec-00 18Yrs0Mon,2 2 2059 F UR 10.00 10.00 95.00 47.50 81.00 88.00 83.00 252.00 300.00 84.00 42.00 89.50 100.00 52.00 52.00 2 EMPLYO OFFICE 12:00:00 AM 1days PO:KENDRAPADA DIST:KENDRAPADA PIN:754211 ODISHA MOB.NO:7381179371 MONALISA SAHOO C/O KAMAL KRISHNA SAHOO QR.NO. A/381(1ST 15-Jul-99 19Yrs5Mon,1 EX- 3 38 F UR 10.00 10.00 95.00 47.50 88.00 72.00 90.00 250.00 300.00 83.33 41.66 89.16 100.00 91.00 91.00 3 1 FLOOR) KOELANGAR 12:00:00 AM 6days SER ROURKELA-14 DIST: SUNDERGARH,PIN- 769014 MOB.NO.7978267029 SAISRITA PALO C/O: SANJAYA KUMAR PALO AT: BURUPADA 24-May-00 18Yrs7Mon,7 4 124 F UR 600.00 553.00 92.16 46.08 86.00 85.00 84.00 255.00 300.00 85.00 42.50 88.58 100.00 63.00 63.00 4 PO:BURUPADA,PS- 12:00:00 AM days HINJILICUT DIST:GANJAM PIN: 761146 ODISHA MOB.NO:7873081728 HILARY NAYAK C/O HIRALAL NAYAK AT- RUDANGIA(GUNJUGU DA) 06-Dec-00 18Yrs0Mon,2 5 1138 F UR 9.50 9.80 93.10 46.55 68.00 90.00 94.00 252.00 300.00 84.00 42.00 88.55 100.00 78.00 78.00 5 PO-RUDANGIA 12:00:00 AM 5days PS-G.UDAYAGIRI TAHASIL-TIKABALI DIST-KANDHAMAL PIN-762100 MOB-8763390558 PRIYA KHANDELWAL C/O SRI SANJAY KHANDELWAL AT: UNIT NO. -

DIRECTORATE of FAMILY WELFARE ODISHA Letter No. 5634 / FWE-XIII-12/2018 Bhubaneswar Dt

DIRECTORATE OF FAMILY WELFARE ODISHA Letter No. 5634 / FWE-XIII-12/2018 Bhubaneswar Dt. 01/10/2018 To The Director , Capital Hospital, Bhubaneswar/ The Director ,Rourkella Govt. Hospital, Rourkella. The Asscociate Professor ,RHC, Jagatsinghpur The Principal, Health & FW. Training Centre, Cuttack/ Sambalpur All Chief District Medical & Public Health Officers. Subject- Circulation of Provisional Gradation List of MPHW(F) Stood as on 01.01.2018 Sir/Mdadam, I am to intimate that the provisional gradation list of regular MPHW(F)/ANM ,who have already completed 10 years of service as on 01.01.2018, has been prepared taking into their first joining as MPHW(F)/ANM on regular basis . The above gradation list is enclosed herewith , which may please be circulated amongst all MPHW(F)/ANM working under your administrative control inviting objections, if any, with regard to their date of birth, qualification, category and date of joining as regular MPHW(F)/ANM etc. and furnish the same with documentary evidence to this Directorate within a period of 21 days from the date of receipt of this letter , positively. In case failure to submit the objections of MPHW(F)/ANM within the stipulated time, it will be treated as final and accordingly the final gradation list of MPHW(F) shall be issued . If any Objections will arise from left out MPHW(F)/ANM after issue of final gradation list, you will be held responsible for such lapses. The objections raised by MPHW(M) may be furnished to this Directorate by email [email protected]. The Provisional Gradation list of MPHW(F)/A.N.M will be made available in the Official Web Site www.nursingodisha.nic.in Please treat this as MOST URGENT. -

The Executive Engineer, RWS&S Division, Berhampur, Ganjam on Behalf of Governor of Odisha Invites Bids in Single Cover &

OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER:RWSS DIVISION:BERHAMPUR Near JaradaBunglow, Pin – 760004, Ph. 0680-2296344 [email protected]@gmail.com Government of Odisha “e” Procurement Notice NATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDING Bid Identification No. EERWSSBAM-26/2020-21 The Executive Engineer, RWS&S Division, Berhampur, Ganjam on behalf of Governor of Odisha invites bids in Single Cover & Double cover system according to the norm of “e” Procurement system in online mode for Supply, drawing, design, construction, testing and commissioning and maintenance of different PWS Schemes and electrification works in GanjamDistrict from the eligible contractors as per DTCN. 1 Name of the work Execution of different works of different P.W.S.Scheme in Ga njam District. 2 No of Work (Tender) 46 Nos. 3 Estimated cost (Approximate) From Rs 5.33Lahs to Rs 115.10 Lakhs 4 Period of completion From 120days to 365 days 5 Date & Time of availability of From 21-01-2021 at11.00 hrs to 05-02-2021upto bid document in the Portal. 17.00 hrs 6 Last date &time for seeking 29-01-2021 up to 17.00 hrs clarification 7 Dt. of opening of Bid 06-02-2021at 11.00 hrs 8 Late date / Time for receipt of 05-02-2021up to 17.00 hrs bids in the Portal 9 Name & address of the Officer Executive Engineer, RWSS Division, Near inviting tender. JaradaBunglow, Berhampur-760004, Dist. Ganjam, Odisha. Further details can be seen from the e-procurement portal https://tendersorissa.gov.in Sd/11.01.2021 Executive Engineer RWS&S Division, Berhampur Immediate Publication Memo No. -

NAME of ELECTED CHAIRMAN and VICE CHAIRMAN Sl

24 NAME OF ELECTED CHAIRMAN AND VICE CHAIRMAN Sl. Name of the Sl. Name of Panchayat Elected Chairman Elected Vice Chairman NO District NO Samiti 1 Angul 1 Angul Niranjan Dehuri Mamata Pradhan 2 Athamalik Minakshee Dalei Babita Karna 3 Kaniha Namita Sahu Tripurari Pradhan 4 Kishorenagar Babita Pradhan Sunil Kumar Pradhan 5 Chendipada Ashok Kumar Pradhan Susama Roul 6 Talcher Brundaban Behera Subarna Sahu 7 Pallahara Mukesh Kumar Pal Lili Pradhan 8 Banarpal Anjali Bhoi Prasanta Kumar Behera 2 Bolangir 1 Agalpur Sunita Majhi Man Mohan Patel 2 Khaprakhol Purnamasi Bariha Prakash Chandra Mehera 3 Gudvela Ashok Chandra Dora Nalini Seth 4 Titilagarh Ramakanti Putel Bhudhara Majhi 5 Turekela Anu Bhue Naukeshi Sipka 6 Deogaon Reena Meher Raju Bag 7 Patnagarh Bhaktabandhu Naik Padmini Sahu 8 Puintala Jamuna Biswal Raghunath Gurandi 9 Bangomunda Ranjubala Behera Mamraj Jain 10 Balangir Golap Bag Jasobanti Baghar 11 Muribahal Hansraj Jain Sundamati Bag 12 Saintala Ahalya Mallik Pramod Kumar Bhoi 13 Loisingha Kanti Seth Jatindra Kumar Patel 3 Balasore 1 Simulia Dharitri Maharana Gouranga Chandra Patri 2 Balasore Narayan Pradhan Supriti Giri 3 Nilgiri Janaki Singh Ramesh Ch. Mohanty 4 Bahanaga Saraswati Mohallik Sanjay Kumar Nayak 5 Khaira Abhilipsa Sahu Jayanta Kumar Rout 6 Soro Attashi Mohapatra Ratikanta Mohanty 7 Jaleswar Sabita Rani Dalei Brajamohan Pradhan 8 Oupada Nirmala Biswal Tilottama Parida 9 Baliapal Bijan Nayak Kabita Das 10 Remuna Sushant Pattnayak Manjulata Das 11 Basta Laxmidhara Das Ranjana Das 12 Bhograi Manju Rani Behera Deepak