SPEAKERSHIP the Hon Tony Smith MP, Speaker of the House of Representatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Speaker of the House of Representatives the Speaker of the House of Representatives the Speaker of the House of Representatives

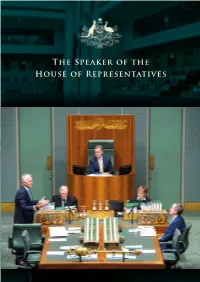

The Speaker of the House of Representatives of the House of The Speaker The Speaker of the House of Representatives The Speaker of the House of Representatives 1 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 ISBN 978-1-74366-502-2 Printed version Prepared by the Department of the House of Representatives Photos of certain former Speakers courtesy of The National Library of Australia and Auspic/DPS (David Foote) 2 THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES The Speaker of the House of Representatives is the Honourable Tony Smith MP. He was elected as Speaker on 10 August 2015. Mr Smith, the Federal Member for Casey, was first elected in 2001, and re-elected at each subsequent election. The Victorian electoral division of Casey covers an area of approximately 2,500 square kilometres, extending from the outer eastern suburbs of Melbourne into the Yarra Valley and Dandenong Ranges. Industries in the electorate include market gardens, orchards, nurseries, flower farms, vineyards, forestry and timber, tourism, light manufacturing and engineering. The Speaker has previously served as the Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister from 30 January 2007 to 3 December 2007, and in a range of Shadow Ministerial positions in the 42nd and 43rd parliaments. Mr Smith has also served on numerous parliamentary committees and was most recently Chair of the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters in the 44th Parliament. The Speaker studied a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) and Bachelor of Commerce at the University of Melbourne. The Speaker is married to Pam and has two sons, Thomas and Angus. THE OFFICE OF SPEAKER The Speakership is the most important office in the House of Representatives and the Speaker, the principal office holder. -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-Four

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-four Proceedings of the Twenty-fourth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Traders Hotel Brisbane, 159 Roma Street, Hobart — August 2012 © Copyright 2014 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction Julian Leeser The Fourth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration Senator the Honourable George Brandis In Defence of Freedom of Speech Chapter One The Honourable Ian Callinan Defamation, Privacy, the Finkelstein Report and the Regulation of the Media Chapter Two Michael Sexton Flights of Fancy: The Implied Freedom of Political Communication 20 Years On Chapter Three The Honourable Justice J. D. Heydon Sir Samuel Griffith and the Making of the Australian Constitution Chapter Four The Honourable Christian Porter Federal-State Relations and the Changing Economy Chapter Five The Honourable Richard Court A Federalist Agenda for Coast to Coast Liberal (or Labor) Governments Chapter Six Keith Kendall The Case for a State Income Tax Chapter Seven Josephine Kelly The Constitutionality of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act i Chapter Eight The Honourable Gary Johns Native Title 20 Years On: Beyond the Hyperbole Chapter Nine Lorraine Finlay Indigenous Recognition – Some Issues Chapter Ten J. B. Paul Speaker of the House Contributors ii Introduction Julian Leeser The 24th Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society was held in Brisbane during the weekend of 17-19 August 2012. It marked the 20th anniversary of the Society’s birth. 1992 was undoubtedly a momentous year in Australia’s constitutional history. On 2 January 1992 the perspicacious John and Nancy Stone decided to incorporate the Samuel Griffith Society thirteen days after Paul Keating was appointed Prime Minister. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1985 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT THURSDAY, 21 FEBRUARY 1985 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Thursday, the twenty-first day of February, in the thirty-fourth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and eighty-five. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of busi- ness pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Douglas Maurice Blake, VRD, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Alan Robert Browning, Deputy Clerk, Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Deputy Clerk and Lynette Simons, Acting Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION NINIAN STEPHEN By His Excellency the Governor-General Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Whereas by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is pro- vided, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, Sir Ninian Martin Stephen, Governor-General of the Common- wealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Thursday, 21 February 1985 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business. And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 11.00 o'clock in the morning on Thursday, 21 February 1985. -

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-Funded Flights Taken by Former Mps and Their Widows Between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed by Total Cost of All Flights Taken

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-funded flights taken by former MPs and their widows between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed by total cost of all flights taken NAME PARTY No OF COST $ FREQUENT FLYER $ SAVED LAST YEAR IN No OF YEARS IN FLIGHTS FLIGHTS PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Ian Sinclair Nat, NSW 701 $214,545.36* 1998 25 Frederick M Chaney Lib, WA 303 $195,450.75 19 $16,343.46 1993 20 Gordon Bilney ALP, SA 362 $155,910.85 1996 13 Barry Jones ALP, Vic 361 $148,430.11 1998 21 Dr Michael Wooldridge Lib, Vic 326 $144,661.03 2001 15 Margaret Reynolds ALP, Qld 427 $142,863.08 2 $1,137.22 1999 17 John Dawkins ALP, WA 271 $142,051.64 1994 20 Graeme Campbell ALP/Ind, WA 350 $132,387.40 1998 19 John Moore Lib, Qld 253 $131,099.83 2001 26 Alan Griffiths ALP, Vic 243 $127,487.54 1996 13 Fr Michael Tate ALP, Tas 309 $100,084.02 11 $6,211.37 1993 15 Tim Fischer Nat, NSW 289 $99,791.53 3 $1,485.57 2001 17 Noel Hicks Nat, NSW 336 $99,668.10 1998 19 Neil Brown Lib, Vic 214 $99,159.59 1991 17 Janice Crosio ALP, NSW 154 $98,488.80 2004 15 Daniel Thomas McVeigh Nat, Qld 221 $96,165.02 1988 16 Martyn Evans ALP, SA 152 $92,770.46 2004 11 Neal Blewett ALP, SA 213 $92,770.32 1994 17 Michael Townley Lib/Ind, Tas 264 $91,397.09 1987 17 Chris Schacht ALP, SA 214 $91,199.03 2002 15 Peter Drummond Lib, WA 198 $87,367.77 1987 16 Ian Wilson Lib, SA 188 $82,246.06 6 $1,889.62 1993 24 Percival Clarence Millar Nat, Qld 158 $82,176.83 1990 16 Bruce Lloyd Nat, Vic 207 $82,158.02 7 $2,320.21 1996 25 Prof Brian Howe ALP, Vic 180 $80,996.25 1996 19 Nick Bolkus ALP, SA 147 $77,803.41 -

News and Notes 1

Autumn 2001 News and Notes 1 News and notes Although this is a magazine with a new name and a new cover, Australasian Parliamentary Review is very much the successor of Legislative Studies . It will maintain the volume sequence of its forerunner. The cover, though new, is recognisably similar to that of its predecessor. The practice of alternating the traditional parliamentary colours of red and green will continue. The early editors of Legislative Studies had the difficult task of simply establishing the magazine and attracting sufficient articles to support publication on a twice-yearly basis. The recent editors have made notable progress in building its reputation as an academic publication, with supporting procedures for appraisal and peer review of articles. Most new editors, on appointment, have various ambitions for development of a magazine during their time in the chair. My aims are to build a strong review section dealing with publications about parliament and legislative processes, and also about constitutional, electoral, accountability and ethical matters relevant to political life and the workings of parliaments. Scrutiny of government will be a prominent theme. Likewise, political history and biography will have a recognised place in APR coverage. Another objective of APR will be to provide prompt reports on recent events of major significance. The aim will be to reach beyond the type of coverage available in newspapers. For this reason it is intended to include reports on general elections for parliaments in the various jurisdictions covered by the readership of APR and, where possible, elsewhere. In this number, for instance, not only has it been possible to secure analyses of the Western Australian and Queensland state elections, there is also an on- the-spot report from Jerusalem on the recent prime ministerial election in Israel as well commentary on electoral aspects of Fiji’s political troubles. -

Disorderly Conduct in the House of Representatives from 1901 to 2013

RESEARCH PAPER, 2013–14 11 DECEMBER 2013 ‘That’s it, you’re out’: disorderly conduct in the House of Representatives from 1901 to 2013 Rob Lundie Politics and Public Administration Executive summary • Of the 1,093 members who have served in the House of Representatives from 1901 to the end of the 43rd Parliament in August 2013, 300 (27.4%) have been named and/or suspended or ‘sin binned’ for disorderly behaviour in the Chamber. This study outlines the bases of the House’s authority to deal with disorderly behaviour, and the procedures available to the Speaker to act on such behaviour. It then analyses the 1,352 instances of disorderly behaviour identified in the official Hansard record with a view to identifying patterns over time, and the extent and degree of such behaviour. It does not attempt to identify the reasons why disorderly behaviour occurs as they are quite complex and beyond the scope of this paper. • The authority for the rules of conduct in the House of Representatives is derived from the Australian Constitution. The members themselves have broad responsibility for their behaviour in the House. However, it is the role of the Speaker or the occupier of the Chair to ensure that order is maintained during parliamentary proceedings. This responsibility is derived from the standing orders. Since its introduction in 1994, the ‘sin bin’ has become the disciplinary action of choice for Speakers. • With the number of namings and suspensions decreasing in recent years, the ‘sin bin’ (being ordered from the chamber for one hour) appears to have been successful in avoiding the disruption caused by the naming and suspension procedure. -

To View a Century Downtown: Sydney University Law School's First

CENTURY DOWN TOWN Sydney University Law School’s First Hundred Years Edited by John and Judy Mackinolty Sydney University Law School ® 1991 by the Sydney University Law School This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism, review, or as otherwise permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Typeset, printed & bound by Southwood Press Pty Limited 80-92 Chapel Street, Marrickville, NSW For the publisher Sydney University Law School Phillip Street, Sydney ISBN 0 909777 22 5 Preface 1990 marks the Centenary of the Law School. Technically the Centenary of the Faculty of Law occurred in 1957, 100 years after the Faculty was formally established by the new University. In that sense, Sydney joins Melbourne as the two oldest law faculties in Australia. But, even less than the law itself, a law school is not just words on paper; it is people relating to each other, students and their teachers. Effectively the Faculty began its teaching existence in 1890. In that year the first full time Professor, Pitt Cobbett was appointed. Thus, and appropriately, the Law School celebrated its centenary in 1990, 33 years after the Faculty might have done. In addition to a formal structure, a law school needs a substantial one, stone, bricks and mortar in better architectural days, but if pressed to it, pre-stressed concrete. In its first century, as these chapters recount, the School was rather peripatetic — as if on circuit around Phillip Street. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, 10 JUNE 2021 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Mental Health The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Resources ........................ The Hon. J Symes, MLC Minister for Transport Infrastructure and Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop ........................................................ The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Training and Skills, and Minister for Higher Education .... The Hon. GA Tierney, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Roads and Road Safety .. The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services and Minister for Equality .................................................... -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, 11 NOVEMBER 2020 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Mental Health The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Minister for Regional Development, Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Resources The Hon. J Symes, MLC Minister for Transport Infrastructure and Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop ........................................................ The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Training and Skills, and Minister for Higher Education .... The Hon. GA Tierney, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Roads and Road Safety .. The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services and Minister for Equality .................................................... -

Disorderly Conduct in the House of Representatives from 1901 to 2016

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2016–17 22 DECEMBER 2016 ‘That's it, you’re out’: disorderly conduct in the House of Representatives from 1901 to 2016 Rob Lundie Politics and Public Administration Executive summary • Of the 1,136 members who have served in the House of Representatives from 1901 to the end of the 44th Parliament in May 2016, 329 (30 per cent) have been penalised for disorderly behaviour in the Chamber. This study outlines the bases of the House’s authority to deal with disorderly behaviour, and the procedures available to the Speaker to act on such behaviour. It then analyses the 1,876 instances of disorderly behaviour identified in the official Hansard record with a view to identifying patterns over time, and the extent and degree of such behaviour. • The authority for the rules of conduct in the House of Representatives is derived from the Australian Constitution. Members themselves have broad responsibility for their behaviour in the House. However, it is the role of the Speaker, or the occupier of the Chair, to ensure that order is maintained during parliamentary proceedings. This responsibility is derived from the Standing Orders. • Since its introduction in 1994, the ‘sin bin’ has become the disciplinary action of choice for speakers, while the number of namings and suspensions has decreased. The sin bin appears to have been successful in avoiding the disruption caused by the naming and suspension procedure. However, as the number of sin bin sanctions has increased, it may be that this penalty has contributed to greater disorder because members may view it as little more than a slap on the wrist and of little deterrent value. -

Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Official Hansard No. 11, 2001 MONDAY, 6 AUGUST 2001 THIRTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—TENTH PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERNET The Votes and Proceedings for the House of Representatives are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/house/info/votes Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard SITTING DAYS—2001 Month Date February 6, 7, 8, 26, 27, 28 March 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 26, 27, 28, 29 April 2, 3, 4, 5 May 9, 10, 22, 23, 24 June 4, 5, 6, 7, 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28 August 6, 7, 8, 9, 20, 21, 22, 23, 27, 28, 29, 30 September 17, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26, 27 October 15, 16, 17, 18, 22, 23, 24, 25 November 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 20, 21, 22 December 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM THIRTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—TENTH PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency the Right Reverend Dr Peter Hollingworth, Officer of the Order of Australia, Officer of the Order of the British Empire House of Representatives Officeholders Speaker—The Hon. -

44Th Parliament in Review

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2016–17 DATE 24 NOVEMBER 2016 44th Parliament in review Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations .............................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 Background ................................................................................................. 4 Chronology of events and developments ...................................................... 5 2014 .................................................................................................................... 5 2015 .................................................................................................................... 5 2016 .................................................................................................................... 6 The path to the double dissolution election .................................................. 7 Prorogation and recall of Parliament ................................................................. 8 The Budget and the double dissolution.............................................................. 9 The Speaker ................................................................................................ 9 Elections ............................................................................................................