FIGHTING COCACOLANISATION in PLACHIMADA: Water, Soft Drinks and a Tragedy of the Commons in an Indian Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Products Are Pareve Unless Indicated D=Dairy Or M=Meat

New to All products are pareve unless indicated D=Dairy or M=Meat. Due to limited space, this list contains only products manufactured by companies and/or plants certified within the last three months. Brands listed directly beneath one another indicate that the product list immediately below is identical for all brands. PR ODUCTS ARE CERTIF I E D ONLY WH EN BEARING TH E SYMBOL Compiled by Zeh a va Ful d a 4c Seltzer Citrus Mist Green Tea Cappuccino French Vanilla Iced Tonic Water Golden Cola Champagne Green Tea W/ginseng & Plum Juice Tea Mix ........................................D Tropical Punch Wild Cherry Seltzer Green Tea W/honey & Ginseng Cappuccino Mix-coffee Flavor..........D Vanilla Cream Soda Green Tea With Ginseng & Asia Plum Cappuccino Mix-mocha Flavor........D Wildberry Seltzer American Dry Green Tea With Ginseng And Honey Iced Tea Mix-decaffeinated Yellow Lightning Club Soda Green Tea With Honey (64oz) Iced Tea Mix-lemon Flavor Green Tea With Honey And Ginseng Anderson Erickson Iced Tea Mix-peach Flavor Adirondack Clear ‘n’ Natural Honey Lemon Premium Tea Blue Raspberry Fruit Bowl................D Iced Tea Mix-raspberry Flavor Blackberry Soda Kahlua Iced Coffee ..........................D Lite Egg Nog....................................D Iced Tea Mix-sugar Free Cherry Soda Latte Supreme..................................D Lemonade Flavor Drink Mix Cranberry Soda Lemon Iced Tea Diet Cranberry Soda Anytime Drink Crystals Lemon Tea A & W Diet Loganberry Soda Lemonade W/10% Real Lemon Juice Cream Soda Diet Raspberry Lime Soda -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Filozofická Bakalářská Práce

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce Русская кухня в Чехии, чешская кухня в России Milina Lubneva Plzeň 2021 1 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra germanistiky a slavistiky Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina-ruština Bakalářská práce Русская кухня в Чехии, чешская кухня в России Lubneva Milina Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Bohuslava Němcová, Ph.D. Katedra germanistiky a slavistiky Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2021 2 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2021 ....................... 3 Poděkovaní Zde bych ráda poděkovala paní Mgr. Bohuslavě Němcové za konzultace, promyšlené komentáře a rady, které mi poskytovala při zpracování mé bakalářské práce. 4 Оглавление Предисловие ...................................................................................................................... 7 1. Определение национальной кухни ....................................................................... 9 1.1. Определение русской национальной кухни .................................................... 9 1.1.1. Факторы влияния .............................................................................................. 10 1.1.2. Раннее средневековье, базовые элементы пропитания ........................ 12 1.1.3. Период с X по XIII в. ........................................................................................ 13 1.1.4. Период от вторжения монголов -

Sortimentsliste Fassbier / Flaschenbier / Alkoholfreie Getränke

Sortimentsliste Fassbier / Flaschenbier / Alkoholfreie Getränke Gültig Ab: 06.09.2021 24h Bestellung: Tel.: 030/688 901 - 0 Fax: 030/688 901 - 26 E-Mail: [email protected] Ab sofort können Sie bei uns direkt online Ihre Bestellung abschicken. Schicken Sie einfach eine E-Mail mit Ihrer Kundennummer und dem Betreff "Onlinebestellsystem" an: [email protected] Sie bekommen dann Ihre Zugangsdaten und können unser Onlinebestellsystem ganz bequem von jedem Internetfähigen Endgerät nutzen. 24h Bestellung: Tel.: 030/688 901 - 0 Fax: 030/688 901 - 26 E-Mail: [email protected] Ab sofort können Sie bei uns direkt online Ihre Bestellung abschicken. Schicken Sie einfach eine E-Mail mit Ihrer Kundennummer und dem Betreff "Onlinebestellsystem" an: [email protected] Sie bekommen dann Ihre Zugangsdaten und können unser Onlinebestellsystem ganz bequem von jedem Internetfähigen Endgerät nutzen. Liefer- und Zahlungsbedingungen 1. Rechnungen sind unverzüglich nach Empfang und ohne jeden Abzug zu bezahlen. Vom Kunden sind bei Zahlung Name, Kunden-Nummer, Rechnungsnummer und Rechnungsdatum anzugeben. Die Getränke Preuss Münchhagen GmbH ist berechtigt, eingehende Zahlungen des Kunden nach ihrer Wahl, auch auf ältere Forderungen, gleich welcher Art, zu buchen. Gegen unsere Forderungen kann nur mit unbestrittenen oder rechtskräftig festgestellten Gegenansprüchen aufgerechnet werden. Gegenansprüche, die nicht auf dem selben Vertragsverhältnis beruhen, berechtigen den Kunden nicht zur Zahlungsverweigerung. Die Rechnungen bitten wir umgehend zu prüfen und uns etwaige Unstimmigkeiten innerhalb 14 Tagen nach Rechnungsdatum schriftlich mitzuteilen. Der Kunde hat die gelieferte Ware unverzüglich zu untersuchen und offensichtliche Mängel unverzüglich nach Feststellung schriftlich der Getränke Preuss Münchhagen GmbH mitzuteilen. Ansprüche auf Ersatzlieferung, Vergütung, sowie Ansprüche sonstiger Art sind bei verspäteter Rüge ausgeschlossen. -

Preisliste Mandant: Pass 01.11.2019 Betriebstätte: Zentrale Preisgruppe: PG: Listenpreis (Netto)

Firma: Pass Spirituosen Großhandel Preisliste Mandant: Pass 01.11.2019 Betriebstätte: Zentrale Preisgruppe: PG: Listenpreis (Netto) Art-Nr Bezeichnung Art Spirituosen/Wodka/Deutschland 48231 Abyme Bio Vodka 1,0 STK 48232 Abyme Vodka 0,1 STK 48235 Abyme Vodka 0,35 STK 4521 Adler Wodka Berlin 0,7 STK 16508 Freimeister Quinoa 0,5 STK 16516 Freimeister Wodka 50% 0,5 STK 953 Fürst Bismarck Vodka 0,5 STK 3499 Gorbatschow Black 50 %vol. 0,7 STK 2784 Gorbatschow Platinum 0,7 STK 1154 Gorbatschow Platinum 3,0 STK 1149 Gorbatschow Wodka 0,7 STK 1148 Gorbatschow Wodka 1,0 STK 19501 KAKUZO Tea infused Vodka/ Earl Grey 0,7 STK 4115 Mampe Wodka 0,7 STK 4959 Our Berlin Vodka 0,35 STK 4987 SOS Spirit of Sylt Vodka Black Label 0,7 STK 4986 SOS Spirit of Sylt Vodka Premium 0,7 STK 3821 Schilkin Vodka 0,7 STK 3824 Three Sixty Vodka 1,0 STK 3407 Wodka Hausmarke 1,0 STK Spirituosen/Wodka/USA 2659 Skyy Vodka USA 0,7 STK 2836 Skyy Vodka USA 1,0 STK 1248 Skyy Vodka Vanilla 0,7 STK 4602 Smirnoff Espresso Twist 1,0 STK 2519 Smirnoff Green Apple Twist 0,7 STK 1962 Smirnoff Peppermint Twist 0,7 STK 3122 Smirnoff Vodka Black Label 0,7 STK 3631 Smirnoff Vodka Black Label 1,0 STK 1961 Smirnoff Vodka Blue Label 1,0 STK 2992 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 0,5 STK 1960 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 0,7 STK 1959 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 1,0 STK 23 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 3,0 STK 38243 Three Sixty Vodka 3,0 STK 4916 Tito's handmade Vodka 0,7 STK Spirituosen/Wodka/Frankreich 1889 Alpha Noble Vodka, Frankreich 0,5 STK 2318 Alpha Noble Vodka, Frankreich 0,7 STK 2141 Alpha Noble Vodka, -

Munduko Kola-Freskagarriak

08 IKAS UNITATEA Herrialdea austria munduko kola-freskagarriak Edari komertzialak, Kontsumo arduratsua, Elikagaien merkataritza multina- Landutako edukiak zionala. Gomendatutako adina 13-15 urte. Balio etikoak eta Ekonomia. Geografia, Historia, eta Biologia ere zeharka Ikasgaiak lantzen dira. Metodologiak Talde-lana, Ideia-zaparrada, Jolasa, Eztabaida gidatua, Ikerketa autonomoa. Egilea Südwind elkartea (Euskal Fondoak egokitua). Oinarrizko gaitasunak 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 / C, E • Gazteen gustuko diren edari-freskagarriak era kritikoan aztertzea. • Edarien merkatu globalaren egiturei eta kontzentrazioari buruzko ezagutzak lortzea. • Markek duten indarrari eta kontsumitzaile gisa dugun portaeraren garrantziari buruz hausnartzea. Ikasketa-helburuak • Kola-edarien osagaiei buruzko eta munduko historian izan duten eginkizunari buruzko ezagutzak lortzea. • Ekoizpen- eta merkataritza-bide alternatiboak ezagutzea. • Informazio-iturri desberdinak ulertzea eta aztertzea. • Informazioa norbere kabuz bildu, prestatu eta aurkeztea. • Argudioak eta ikuspuntu desberdinak formulatu eta adieraztea. ELIKADURA ETA HEZKUNTZA GLOBALA HEZKUNTZA FORMALEAN eathink 55 IKAs-UNITATeAReN gARApeNA 1. saioa (60’) KOLA-FRESKAGARRIEN KONTSUMOA EKonomiA 10’ 1.1 FRESKAGARRIAK ETA GU Gaia kokatzeko ikasleek galdera hauei buruz eztabaidatuko dute binaka: • Zer edari duzue gustukoen? ? • Zenbat freskagarri edaten duzue astean? ? • Gazteek freskagarri gehiegi edaten duzue? ? • Freskagarri bat edatean, ba ote dakigu zer hartzen ari garen? Emaitzak txarteletan idatzi eta ikasgelan -

Preisliste 04.03.2021 Preisgruppe: (Netto)

Preisliste 04.03.2021 Preisgruppe: (Netto) Art-Nr Bezeichnung Art Spirituosen/Wodka/Deutschland 48232 Abyme Vodka 0,1 STK 4521 Adler Wodka Berlin 0,7 STK 49121 Berliner Brandstifter Vodka 0,7 STK 16508 Freimeister 154 Quinoa Wodka 0,5 STK 16541 Freimeister 157 Dinkel Wodka 0,5 STK 953 Fürst Bismarck Vodka 0,5 STK 3499 Gorbatschow Black 50 %vol. 0,7 STK 2784 Gorbatschow Platinum 0,7 STK 1154 Gorbatschow Platinum 3,0 STK 1149 Gorbatschow Wodka 0,7 STK 1148 Gorbatschow Wodka 1,0 STK 19501 Kakuzo Tea Infused Vodka / Earl Grey 0,7 STK 4115 Mampe Wodka 0,7 STK 4987 SOS Spirit of Sylt Vodka Black Label 0,7 STK 4986 SOS Spirit of Sylt Vodka Premium 0,7 STK 46831 Sash & Fritz Wodka 1,0 STK 3821 Schilkin Vodka 0,7 STK 3824 Three Sixty Vodka 1,0 STK 3407 Wodka Hausmarke 1,0 STK Spirituosen/Wodka/USA 2659 Skyy Vodka 0,7 STK 2836 Skyy Vodka 1,0 STK 1248 Skyy Vodka Vanilla 0,7 STK 4602 Smirnoff Espresso Twist 1,0 STK 3122 Smirnoff Vodka Black Label 0,7 STK 3631 Smirnoff Vodka Black Label 1,0 STK 1961 Smirnoff Vodka Blue Label 1,0 STK 2992 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 0,5 STK 1960 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 0,7 STK 1959 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 1,0 STK 23 Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 3,0 STK 38243 Three Sixty Vodka 3,0 STK 4916 Tito's Handmade Vodka 0,7 STK Spirituosen/Wodka/Frankreich 2318 Alpha Noble Vodka 0,7 STK 2141 Alpha Noble Vodka 1,0 STK 3892 Ciroc Red Berry Vodka 0,7 STK 3893 Ciroc Vodka 0,7 STK 1867 Ciroc Vodka 1,75 STK 536 Ciroc Vodka 3,0 STK 4673 Ciroc Vodka Coconut 0,7 STK 3858 Grey Goose Vodka 0,7 STK 2165 Grey Goose Vodka 1,5 STK 6058 Pyla excellium -

Alkoholfreies Getränke Sortiment

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx [in Alphabetischer Reihenfolge nach MaterialGruppe, Hersteller und Artikelbezeichnung] Alkoholfreies Getränke Sortiment 2020 www.HFS-Getraenke.de | Vertrieb[at]HFS-Getraenke.de Öko-Kontrollstelle DE-ÖKO-006 Stand vom: 26.08.2020 Material Artikel- Sortiment Pfand- Nummer Materialbezeichnung & Gebindeinhalt Wert . , .3 .4 .5 .7 .6 AFG BEHÄLTER / POSTMIX SORTIMENT AFG Behälter / Postmix - Bauer Fruchtsaft Bauer Apfelsaft B.i.B. 10 L 0461701 letzte Preisänderung am: 01.03.2020 um -0,50 € 0012843 Bauer Multivitaminnek.Diät B.i.B. 10 L Bauer Orangensaft B.i.B. 10 L 0002613 letzte Preisänderung am: 01.03.2020 um -0,80 € AFG Behälter / Postmix - Coca-Cola 0002623 Coca-Cola Postmix B.i.B. 20 L* 0015537 Fanta Orange Splash Postmix B.i.B. 10 L* 0004200 Lift Apfelsaftschorle Postmix B.i.B. 5L* 0002616 Sprite Postmix B.i.B. 10 L* AFG Behälter / Postmix - Eckes - Granini Granini little BIC Pink Grapef.Ew 2x5,00 0004399 letzte Preisänderung am: 01.04.2018 um 1,00 € AFG Behälter / Postmix - Kelterei Walther GmbH Arnsdorf Walther Apfelsaft Klar B.i.B. 10 L 0462340 letzte Preisänderung am: 01.01.2018 um 0,97 € Walther Apfelsaft Naturtrüb B.i.B. 10 L 0462342 letzte Preisänderung am: 01.01.2018 um 0,97 € Walther Heidelbeernektar B.i.B. 3 L 0002779 letzte Preisänderung am: 01.04.2015 um -4,63 € 0462348 Walther Orangensaft B.i.B. 3,00 AFG Behälter / Postmix - Menschel Limo GmbH Menschel Himbeer-Fassbrause 20 L 0013654 1 x 30,00 € letzte Preisänderung am: 01.05.2020 um 1,00 € Menschel -

Preisänderungsübersicht Vor 2020

PREISÄNDERUNGSLISTE [Alle Preise sind Netto Erhöhungssätze der Netto-Abgabepreise.] Ab sofort finden sie alle Preisänderungen auch unter www.HFS-Getraenke.de sowie weitere Informationen, Aktionen, Hinweise zu Veranstaltungen und die aktuellen Informationen zu unseren Not- und Wochenenddiensten. Stand Februar 2021 … Material Materialkurztext & Gebinde Status Betrag Einh. pro ME Gültig ab .62 .7 .8 .92 .103 .114 .122 .133 702145|| BRAUEREI GEBR. MAISEL KG 0001018 Maisel's Weisse Alkoholfrei Mw 20x0,50 A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0001019 Maisel's Weisse Dunkel Mw 20x0,50 A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0001020 Maisel's Weisse Kristall Mw 20x0,50 A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0001022 Aktien Zwick'l Kellerbier Mw 20x0,50 BV A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0001665 Bayreuther Hell Mw 20x0,50 A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0002102 Aktien Landbier Fränk. Dkl.Mw 20x0,50 BV A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0002310 Maisel's Weisse Alkoholfrei Mw 24x0,33 A 0,55 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0002312 Maisel's Weisse Original Mw 24x0,33 A 0,55 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0003783 Maisel's Weisse Light Mw 20x0,50 A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0006078 Maisel's Weisse Original Mw 20x0,50 A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0011228 Bayreuther Hefe-Weissbier Mw 20x0,50 A 0,65 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0016875 Bayreuther Hell Mw 20x0,33 A 0,50 EUR 1 KAS 01-07-2021 0042806 Bayreuther Hell Fass 50 L A 4,50 EUR 1 FAS 01-07-2021 0201602 Maisel's Weisse Original Fass 30 L A 2,70 EUR 1 FAS 01-07-2021 0201603 Aktien Original 1857 Fass 30 L A 2,70 EUR 1 FAS 01-07-2021 0201604 Aktien Landbier Fränkisch Dkl. -

Foodwatch-Marktstudie 2018: So Zuckrig Sind "Erfrischungsgetränke

Marktstudie 2018 SO ZUCKRIG SIND „ERFRISCHUNGSGETRÄNKE“ IN DEUTSCHLAND – IMMER NOCH IMPRESSUM INHALT HERAUSGEBER Martin Rücker (v.i.s.d.p.) foodwatch e. V. Was haben wir untersucht? 4 Brunnenstraße 181 10119 Berlin Telefon +49 (0) 30 / 24 04 76 - 0 Ergebnisse und foodwatch-Forderungen 8 Fax +49 (0) 30 / 24 04 76 - 26 E-Mail [email protected] www.foodwatch.de Ausgewählte Hersteller im Vergleich 12 SPENDENKONTO foodwatch e. V. gls Gemeinschaftsbank IBAN DE 5043 0609 6701 0424 6400 Getränke mit mehr als 8 Prozent Zucker 14 BIC GENO DEM 1 GLS BILDHINWEIS Zuckermotiv auf dem Titel: Getränke mit 5,1 bis 8 Prozent Zucker © fotolia.com_pixelrobot 24 PRODUKTRECHERCHE unter Mitarbeit von Luis Brendel Getränke mit 0,6 bis 5 Prozent Zucker 30 LAYOUT UND GRAFIKEN Annette Klusmann. puredesign. STAND Getränke mit bis zu 0,5 Prozent Zucker 39 September 2018 2 3 MARKTSTUDIE 2018 gaben oder -steuern auf Zuckergetränke erlassen. In mehreren Fällen ist FOODWATCH-MARKTSTUDIE 2018: diese Abgabe nach Zuckergehalt gestaffelt und dient so als Anreiz für die GROSSTEIL DER „ERFRISCHUNGSGETRÄNKE“ Hersteller, weniger Zucker in ihre Getränke zu mischen.10 NACH WIE VOR ÜBERZUCKERT WAS UND WIE HABEN WIR GETESTET? WAS IST DAS PROBLEM? foodwatch hat zum zweiten Mal den Markt der „Erfrischungsgetränke“ in Deutschland umfassend untersucht. Wir wollten herausfinden, wie stark das Zuckergesüßte Getränke gelten laut der Weltgesundheitsorganisation (WHO) aktuelle Angebot an „Erfrischungsgetränken“ gesüßt ist. Dazu haben wir im als „eine der Hauptursachen“ für die Entstehung -

Ikas-Unitatea

euskalfondoa.org/eu/eathink IKAS-UNITATEA Ikas-Unitatearen Munduko kola-freskagarriak izenburua Ikasleen gomendatutako 13-15 adina Ikastetxea - Egilea Südwind elkartea (Austria). Euskal Fondoak egokitua. Balio etikoak eta Ekonomia. Geografia, Historia, eta Biologia Ikasgaia(k) ere zeharka lantzen da. Edari komertzialak, kontsumo arduratsua, elikagaien Landutako gaiak merkataritza multinazionala Erabilitako Talde-lana, ideia-jarioa, lehiaketa, antolatutako eztabaidak, metodologiak ikerketa autonomoa. Zehar-konpetentziak: - Hitzez, hitzik gabe eta modu digitalean komunikatzeko konpetentzia. - Ikasten eta pentsatzen ikasteko konpetentzia. - Elkarbizitzarako konpetentzia. Oinarrizko gaitasunak - Ekimenerako eta ekiteko espiriturako konpetentzia. - Izaten ikasteko konpetentzia. Diziplina barruko konpetentziak: - Zientziarako konpetentzia. - Gizarterako eta herritartasunerako konpetentzia. - Gazteen gustuko diren edari-freskagarriak era kritikoan aztertu. - Edarien merkatu globalaren egiturei eta kontzentrazioari buruzko ezagutzak lortu. - Markek duten indarrari eta kontsumitzaile gisa dugun portaeraren garrantziari buruz hausnartu. Ikasketa-helburuak - Kola-edarien osagaiei eta munduko historian izan duten eginkizunari buruzko ezagutzak lortu. - Ekoizpen- eta merkataritza-bide alternatiboak ezagutu. - Informazio iturri desberdinak ulertzea eta aztertu. - Informazioa norbere kabuz bildu, prestatu eta aurkeztu. - Argudioak eta ikuspuntu desberdinak formulatu eta adierazi. 1 euskalfondoa.org/eu/eathink Ikas-unitatearen garapena 1. Saioa: Arazoaren -

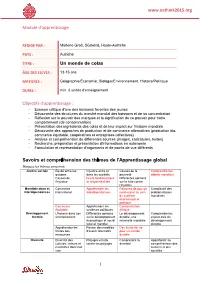

Module D'apprentissage Un Monde De

www.eathink2015.org Module d'apprentissage REDIGE PAR : Marlene Groß, Südwind, Haute-Autriche PAYS : Autriche TITRE : Un monde de colas ÂGE DES ELEVES : 13-15 ans MATIERES : Géographie/Économie, Biologie/Environnement, Histoire/Politique DUREE : min. 3 unités d'enseignement Objectifs d'apprentissage : - Examen critique d'une des boissons favorites des jeunes - Découverte des structures du marché mondial des boissons et de sa concentration - Réflexion sur le pouvoir des marques et la signification de ce pouvoir pour notre comportement (de consommation) - Présentation des ingrédients des colas et de leur impact sur l'histoire mondiale - Découverte des approches de production et de commerce alternatives (production bio, commerce équitable, coopératives et entreprises collectives) - Analyse et compréhension de différentes sources (images, caricatures, textes) - Recherche, préparation et présentation d'informations en autonomie - Formulation et représentation d'arguments et de points de vue différents Savoirs et compréhension des thèmes de l'Apprentissage global Marquez les thèmes concernés Justice sociale Équité entre les Injustice entre et Causes de la Comprendre les groupes dans les sociétés pauvreté débats mondiaux Causes de Droits fondamentaux Différentes opinions l'injustice et responsabilités sur la lutte contre l'injustice Mondialisation et Commerce Appréhender les Relations de pouvoir Complexité des interdépendances international interdépendances nord-sud et au sein problématiques du système mondiales économique et politique Commerce