A Guide to Mourning Customs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

Vnka Vtupr ,Ufzk Vuj Ic Rzghkt

Parshas Korach 5775 Volume 14, Issue 34 P ARSHA I N SI G H T S P O N S O R Korach… separated himself… they stood before Mo she with two hundred vnka vtupr ,ufzk and fifty men… they gathered against Moshe and Aaron… (16:1 - 3) OUR UNCLE Korach gathered the entire assembly against them… (16:19) vuj ic rzghkt How did Korach succeed in arousing the people against Moshe. Moshe was their savior. SPONSORED BY Bnai Yisroel had been ensla ved in a hopless situation in Mitzrayim, and Moshe came and DR. YITZCHOK KLETTER turned the situation around, until the great king Pharoah went running thropugh the4 AND streets of Goshen in middle of the night looking for Moshe, to send Bani Yisroel out. FRIEDA LEAH KLETTER Moshe was the one who as cended Har Sinai and brought the Torah to Bnai Yisroel. he was the one who spoke directly to Hashem, and helped Bnai Yisroel with their food in the desert. All issues were brought to Moshe. DILEMMA How could Bnai Yisroel forget this all, and turn against Moshe? Al l the miraculous things And Korach took… (16:1) Moshe did should have caused them to recognize the G-dliness that Moshe had? Did they Hashem told Bnai Yisroel to take from not see the shining countenance of Moshe, on account of Hashem’s Presence resting on him? the Egyptians their expensive utensils upon departing from t heir land. Furthermore, unfortunately people sin on a daily basis. Why was Korach’s sin so severe, However, Hashem’s instructions were that all involved were destroyed, with no remembrance? They were swallowed into the only for those who had been their slaves. -

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3 Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50Am Mincha/Maariv 6:20Pm Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30Pm FRIDAY, OCTOBE

THE BAYIT BULLETIN MOTZEI SHABBAT, SEPTEMBER 21 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3 Maariv/Shabbat Ends (LLBM) 7:40pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50am Selichot Concert 9:45pm Mincha/Maariv 6:20pm Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 22 Shacharit 8:30am FRIDAY, OCTOBER 4 Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:05, 7:50am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Candle Lighting 6:15pm Mincha/Maariv 6:25pm TUESDAY & WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24-25 Shacharit with Selichot 6:20, 7:50am SHABBAT SHUVA, OCTOBER 5 Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm Shacharit 7:00, 8:30am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Mincha 5:25pm MONDAY & THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 23 & 26 Shabbat Shuva Drasha 5:55pm Maariv/Havdalah 7:16pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:15, 7:50am Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6 Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Shacharit with Selichot 8:30am FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27 Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:20, 7:50am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Candle Lighting 6:27pm Mincha 6:37pm MONDAY, OCTOBER 7 Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50am SHABBAT, SEPTEMBER 28 Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Shacharit 7:00am, 8:30am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Mincha 6:10pm Maariv/Shabbat Ends 7:28pm TUESDAY, OCTOBER 8 - EREV YOM KIPPUR SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 29: EREV ROSH HASHANA Shacharit with Selichot 6:35, 7:50am Shacharit w/ Selichot and Hatarat Nedarim 7:30am Mincha 3:30pm Candle Lighting 6:23pm Candle Lighting 6:09pm Mincha/Maariv 6:33pm Kol Nidre 6:10pm Fast Begins 6:27pm MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 30: ROSH HASHANA 1 Shacharit WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 9 - YOM KIPPUR Main Sanctuary and Social Hall -

Yeshivat Har Etzion Virtual Beit Midrash Project(Vbm)

Yeshivat Har Etzion Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash (Internet address: [email protected]) PARASHAT HASHAVUA encampment in the beginning of Bemidbar also relates to their ****************************** journey. PARASHAT VAYIKRA ********************************************************** Generally speaking, then, the Book of Vayikra is the This year’s Parashat HaShavua series is dedicated book of commandments which Moshe received in the Mishkan, in loving memory of Dov Ber ben Yitzchak Sank z"l and the Book of Bemidbar is the book of travels. As such, these ********************************************************** two sefarim form the continuation of the final verses of Sefer Dedicated in memory of Matt Eisenfeld z"l and Sara Duker z"l Shemot specifically, and, more generally, the continuation of the on their 20th yahrzeit. Book of Shemot as a whole. God's communication with Moshe Though their lives were tragically cut short in the bombing of Bus and the traveling patterns of Benei Yisrael constitute the two 18 in Jerusalem, their memory continues to inspire. results of the God's Presence in the Mishkan. The first Am Yisrael would have benefitted so much from their expresses the relationship between the Almighty and His people contributions. Yehi zikhram barukh. – through His communion with Moshe, when He presents His Yael and Reuven Ziegler commandments to the nation. The second expresses this ************************************************************************** relationship through God's direct involvement in the nation's navigation through the wilderness, where He leads like a King striding before His camp. Introduction to Sefer Vayikra By Rav Mordechai Sabato Parashat Vayikra: The Voluntary Sacrifices The first seven chapters of Sefer Vayikra deal with the At the very beginning of Sefer Vayikra, both the various types of korbanot (sacrifices) and their detailed laws. -

TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning

TRANSITIONS & CELEBRATIONS: Jewish Life Cycle Guides E EW A TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning Written and compiled by Rabbi John L. Rosove Temple Israel of Hollywood INTRODUCTION The death of a loved one is so often a painful and confusing time for members of the family and dear friends. It is our hope that this “Guide” will assist you in planning the funeral as well as offer helpful information on our centuries-old Jewish burial and mourning practices. Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary (“Hillside”) has served the Southern California Jewish Community for more than seven decades and we encourage you to contact them if you need assistance at the time of need or pre-need (310.641.0707 - hillsidememorial.org). CONTENTS Pre-need preparations .................................................................................. 3 Selecting a grave, arranging for family plots ................................................. 3 Contacting clergy .......................................................................................... 3 Contacting the Mortuary and arranging for the funeral ................................. 3 Preparation of the body ................................................................................ 3 Someone to watch over the body .................................................................. 3 The timing of the funeral ............................................................................... 3 The casket and dressing the deceased for burial .......................................... -

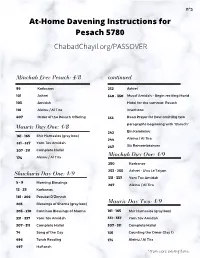

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Lincoln Square Synagogue for As Sexuality, the Role Of

IflN mm Lincoln Square Synagogue Volume 27, No. 3 WINTER ISSUE Shevat 5752 - January, 1992 FROM THE RABBI'S DESK.- It has been two years since I last saw leaves summon their last colorful challenge to their impending fall. Although there are many things to wonder at in this city, most ofthem are works ofhuman beings. Only tourists wonder at the human works, and being a New Yorker, I cannot act as a tourist. It was good to have some thing from G-d to wonder at, even though it was only leaves. Wondering is an inspiring sensation. A sense of wonder insures that our rela¬ tionship with G-d is not static. It keeps us in an active relationship, and protects us from davening or fulfilling any other mitzvah merely by rote. A lack of excitement, of curiosity, of surprise, of wonder severs our attachment to what we do. Worse: it arouses G-d's disappointment I wonder most at our propensity to cease wondering. None of us would consciously decide to deprive our prayers and actions of meaning. Yet, most of us are not much bothered by our lack of attachment to our tefilot and mitzvot. We are too comfortable, too certain that we are living properly. That is why I am happy that we hosted the Wednesday Night Lecture with Rabbi Riskin and Dr. Ruth. The lecture and the controversy surrounding it certainly woke us up. We should not need or even use controversy to wake ourselves up. However, those of us who were joined in argument over the lecture were forced to confront some of the serious divisions in the Orthodox community, and many of its other problems. -

Bar/Bat Mitzvah Fees

www.tbsroslyn.org (516) 621-2288 (Valid Through June 30, 2020) 2019-2020 5779-5780 Rabbi Alan B. Lucas Rabbi Uri D. Allen Cantor Ofer S. Barnoy Executive Director: Donna Bartolomeo Religious School Director: Sharon Solomon Makom Director: Rabbi Uri D. Allen Name: Date: Torah portion: TABLE OF CONTENTS Greetings From Rabbi Lucas .................................................................................................... 4 Mazal Tov! ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Overall Goals Of The Bar/Bat Mitzvah Program .............................................................. 5 Educational and Religious Requirements For Bar and Bat Mitzvah ............................................................................................................ 6 Bar/Bat Mitzvah Programming .............................................................................................. 7 Trope Class .............................................................................................................................. 7 Participation In Our Mishpacha Minyan...................................................................... 7 Bar/Bat Mitzvah Family Programming ....................................................................... 7 The Mitzvah Project ............................................................................................................. 7 The Different Bar/Bat Mitzvah Ceremonies ..................................................................... -

The Laws of Shabbat

Shabbat: The Jewish Day of Rest, Rules & Cholent Meaningful Jewish Living January 9, 2020 Rabbi Elie Weinstock I) The beauty of Shabbat & its essential function 1. Ramban (Nachmanides) – Shemot 20:8 It is a mitzvah to constantly remember Shabbat each and every day so that we do not forget it nor mix it up with any other day. Through its remembrance we shall always be conscious of the act of Creation, at all times, and acknowledge that the world has a Creator . This is a central foundation in belief in God. 2. The Shabbat, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, NCSY, NY, 1974, p. 12 a – (אומן) It comes from the same root as uman .(אמונה) The Hebrew word for faith is emunah craftsman. Faith cannot be separated from action. But, by what act in particular do we demonstrate our belief in God as Creator? The one ritual act that does this is the observance of the Shabbat. II) Zachor v’shamor – Remember and Safeguard – Two sides of the same coin שמות כ:ח - זָכֹוראֶ ת יֹום הַשַבָתלְקַדְ ׁשֹו... Exodus 20:8 Remember the day of Shabbat to make it holy. Deuteronomy 5:12 דברים ה:יב - ׁשָמֹוראֶ ת יֹום הַשַבָתלְקַדְ ׁשֹו... Safeguard the day of Shabbat to make it holy. III) The Soul of the Day 1. Talmud Beitzah 16a Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said, “The Holy One, Blessed be He, gave man an additional soul on the eve of Shabbat, and at the end of Shabbat He takes it back.” 2 Rashi “An additional soul” – a greater ability for rest and joy, and the added capacity to eat and drink more. -

Yom Kippur Morning Sinai Temple Springfield, Massachusetts October 12, 2016

Yom Kippur Morning Sinai Temple Springfield, Massachusetts October 12, 2016 Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die...?1 Who shall live and who shall die...? It was but a few weeks from the pulpit of Plum Street Temple in Cincinnati and my ordination to the dirt of Fort Dix, New Jersey, and the “night infiltration course” of basic training. As I crawled under the barbed wire in that summer night darkness illumined only by machine-gun tracer-fire whizzing overhead, I heard as weeks before the voice of Nelson Glueck, alav hashalom, whispering now in the sound of the war-fury ever around me: carry this Torah to amkha, carry it to your people. Who shall live and who shall die...? I prayed two prayers that night: Let me live, God, safe mikol tzarah v’tzukah, safe from all calamity and injury; don’t let that 50-calibre machine gun spraying the air above me with live ammunition break loose from its concrete housing. And I prayed once again. Let me never experience this frightening horror in combat where someone will be firing at me with extreme prejudice. Who shall live and who shall die...? I survived. The “terror [that stalks] by night” and “the arrow that flies by day” did not reach me.”2 The One who bestows lovingkindnesses on the undeserving carried me safely through. But one of my colleagues was not so lucky. He was a Roman Catholic priest. They said he died from a heart attack on the course that night. I think he died from fright. -

Kiruv Rechokim

l j J I ' Kiruv Rechokim ~ • The non-professional at work 1 • Absorbing uNew Immigrants" to Judaism • Reaching the Russians in America After the Elections in Israel • Torah Classics in English • Reviews in this issue ... "Kiruv Rechokim": For the Professional Only, Or Can Everyone Be Involved? ................... J The Four-Sided Question, Rabbi Yitzchok Chinn ...... 4 The Amateur's Burden, Rabbi Dovid Gottlieb ......... 7 Diary of a New Student, Marty Hoffman ........... 10 THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN A Plea From a "New Immigrant" to Judaism (a letter) 12 0021-6615) is published monthly, except July and August, by the Reaching the Russians: An Historic Obligation, Agudath Israel of America, 5 Nissan Wolpin............................... 13 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription After the Elections, Ezriel Toshavi ..................... 19 Sl2.00 per year; two years, S2LOO; three years, S28.00; out Repairing the Effects of Churban, A. Scheinman ........ 23 side of the United States, $13.00 per year. Single copy, $1.50 Torah Classic in English (Reviews) Printed in the U.S.A. Encyclopedia of Torah Thoughts RABBI NissoN Wotr1N ("Kad Hakemach") . 29 Editor Kuzari .......................................... JO Editorial Board Pathways to Eternal Life ("Orchoth Chaim") ....... 31 DR. ERNST BooENHEIMER Chairman The Book of Divine Power ("Gevuroth Hashem") ... 31 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JosEPH ELIAS JOSEPH fRIEDENSON Second Looks on the Jewish Scene I RABB! MOSHE SttERER Of Unity and Arrogance ......................... 33 If· MICHAEL RorasCHlLD I Business Manager Postscript TttE JEWISH OBSERVER does not I assume responsibility for the I Kashrus of any product or ser Return of the Maggidim, Chaim Shapiro ........... -

The Chosen, Season 1, Episode 2 Fall 2020 Connect to Christ Discipling Community Focus

The Chosen, Season 1, Episode 2 Fall 2020 Connect to Christ Discipling Community Focus Episode 2: Shabbat I don’t understand it myself. I was one way and now I’m completely different. And the thing that happened in between – was Him. So yes, I will know him for the rest of my life! (Mary Magdalene) Thanks for being part of the Fall 2020 Discipling Community focus. We’re focusing on Connect to Christ via the life of Christ by viewing and discussing Season 1 of The Chosen. Beyond the facts, we hope that Discipling Communities rediscover (or discover for the first time) the life, culture, heart, and actions of the gospel stories and allow the spirit and truth of the life of Jesus to help us take next steps in being and growing as biblical, loving, Spirit-filled disciples of Jesus. The Chosen is a multi-season journey through the life of Christ. It has been created from a synoptic perspective instead of focusing on one particular gospel account. Accessing the Video Content The best way to view The Chosen is to download the app for your particular smart device. Search The Chosen in your app store. Open up the app and all the episodes are available there. Then, stream the episode from your smartphone to your TV using your technology of choice. There are lots of options and instructions within the app to get you going. Episodes are also available on YouTube (with ads). We aren’t providing definitive steps because of the many combinations of devices & TVs.