Ballet by Douglas Blair Turnbaugh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide for Teachers and Students

Melody Mennite in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRE AND POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES AND INFORMATION Learning Outcomes & TEKS 3 Attending a ballet performance 5 The story of Cinderella 7 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Choreographer 11 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Composer 12 The Artists who Created Cinderella Designer 13 Behind the Scenes: “The Step Family” 14 TEKS ADDRESSED Cinderella: Around the World 15 Compare & Contrast 18 Houston Ballet: Where in the World? 19 Look Ma, No Words! Storytelling in Dance 20 Storytelling Without Words Activity 21 Why Do They Wear That?: Dancers’ Clothing 22 Ballet Basics: Positions of the Feet 23 Ballet Basics: Arm Positions 24 Houston Ballet: 1955 to Today 25 Appendix A: Mood Cards 26 Appendix B: Create Your Own Story 27 Appendix C: Set Design 29 Appendix D: Costume Design 30 Appendix E: Glossary 31 2 LEARNING OUTCOMES Students who attend the performance and utilize the study guide will be able to: • Students can describe how ballets tell stories without words; • Compare & contrast the differences between various Cinderella stories; • Describe at least one dance from Cinderella in words or pictures; • Demonstrate appropriate audience behavior. TEKS ADDRESSED §117.106. MUSIC, ELEMENTARY (5) Historical and cultural relevance. The student examines music in relation to history and cultures. §114.22. LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH LEVELS I AND II (4) Comparisons. The student develops insight into the nature of language and culture by comparing the student’s own language §110.25. ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND READING, READING (9) The student reads to increase knowledge of own culture, the culture of others, and the common elements of cultures and culture to another. -

2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020

® 2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020 Report Summary The following is a report on the gender distribution of choreographers whose works were presented in the 2019-2020 seasons of the fifty largest ballet companies in the United States. Dance Data Project® separates metrics into subsections based on program, length of works (full-length, mixed bill), stage (main stage, non-main stage), company type (main company, second company), and premiere (non-premiere, world premiere). The final section of the report compares gender distributions from the 2018- 2019 Season Overview to the present findings. Sources, limitations, and company are detailed at the end of the report. Introduction The report contains three sections. Section I details the total distribution of male and female choreographic works for the 2019-2020 (or equivalent) season. It also discusses gender distribution within programs, defined as productions made up of full-length or mixed bill works, and within stage and company types. Section II examines the distribution of male and female-choreographed world premieres for the 2019-2020 season, as well as main stage and non-main stage world premieres. Section III compares the present findings to findings from DDP’s 2018-2019 Season Overview. © DDP 2019 Dance DATA 2019 - 2020 Season Overview Project] Primary Findings 2018-2019 2019-2020 Male Female n/a Male Female Both Programs 70% 4% 26% 62% 8% 30% All Works 81% 17% 2% 72% 26% 2% Full-Length Works 88% 8% 4% 83% 12% 5% Mixed Bill Works 79% 19% 2% 69% 30% 1% World Premieres 65% 34% 1% 55% 44% 1% Please note: This figure appears inSection III of the report. -

Registration Packet 2015-16

! Registration Packet 2015-16 Faculty Artur Sultanov, Artistic Director Mr. Sultanov was born and raised in St. Petersburg, Russia. He trained at Vaganova Ballet Academy and at age 17, joined the Kirov ballet where he danced a classical repertoire. Artur has also performed with Eifman Ballet as a Soloist. In 2000 he moved to San Francisco to join Alonzo King’s Lines Ballet. In 2003 Artur joined Oregon Ballet Theatre. His principal roles at OBT include the Prince in Swan Lake, Ivan in Firebird, and the Cavalier in the Nutcracker, among others. Mr. Sultanov has performed on the stages of the Metropolitan Opera House, Kennedy Center, Bolshoi Ballet Theatre, and the Mariisnky Theatre in his native city of St. Petersburg. In addition to being an accomplished dancer, Mr. Sultanov has also taught extensively throughout his professional career. In the past eight years, Mr. Sultanov has taught and choreographed for the school of Oregon Ballet Theatre and Lines Contemporary Ballet School of San Francisco. His vast experience also includes holding master workshops in the Portland Metro Area, Seaside, OR, Vancouver and Tacoma, Washington. Artur Sultanov is excited to be a part of the Portland dance community and is looking forward to inspiring a new generation of dancers. Vanessa Thiessen Vanessa Thiessen is originally from Portland, OR. She trained at the School of Oregon Ballet Theatre, with James Canfield, and continued on to dance for Oregon Ballet Theatre from 1995-2003. At OBT she danced leading roles in Gissele and Romeo and Juliet. After moving to San Francisco in 2003, she danced with Smuin Ballet, ODC Dance, Amy Seiwert’s Imagery, Opera Parallele and Tanya Bello’s Project b. -

British Ballet Charity Gala

BRITISH BALLET CHARITY GALA HELD AT ROYAL ALBERT HALL on Thursday Evening, June 3rd, 2021 with the ROYAL BALLET SINFONIA The Orchestra of Birmingham Royal Ballet Principal Conductor: Mr. Paul Murphy, Leader: Mr. Robert Gibbs hosted by DAME DARCEY BUSSELL and MR. ORE ODUBA SCOTTISH BALLET NEW ADVENTURES DEXTERA SPITFIRE Choreography: Sophie Laplane Choreography: Matthew Bourne Music: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Gran Partita and Eine kleine Nachtmusik Music: Excerpts from Don Quixote and La Bayadère by Léon Minkus; Dancers: Javier Andreu, Thomas Edwards, Grace Horler, Evan Loudon, Sophie and The Seasons, Op. 67 by Alexander Glazunov Martin, Rimbaud Patron, Claire Souet, Kayla-Maree Tarantolo, Aarón Venegas, Dancers: Harrison Dowzell, Paris Fitzpatrick, Glenn Graham, Andrew Anna Williams Monaghan, Dominic North, Danny Reubens Community Dance Company (CDC): Scottish Ballet Youth Exchange – CDC: Dance United Yorkshire – Artistic Director: Helen Linsell Director of Engagement: Catherine Cassidy ENGLISH NATIONAL BALLET BALLET BLACK SENSELESS KINDNESS Choreography: Yuri Possokhov THEN OR NOW Music: Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 8 by Dmitri Shostakovich, by kind permission Choreography: Will Tuckett of Boosey and Hawkes. Recorded by musicians from English National Music: Daniel Pioro and Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber – Passacaglia for solo Ballet Philharmonic, conducted by Gavin Sutherland. violin, featuring the voices of Natasha Gordon, Hafsah Bashir and Michael Dancers: Emma Hawes, Francesco Gabriele Frola, Alison McWhinney, Schae!er, and the poetry of -

Wsd 2018/19 Uniform Policy

WSD 2018/19 UNIFORM POLICY Proper dance attire must be neat and form fitted so that proper body alignment can be observed. Students are expected to attend ALL classes in full WSD uniform. Proper footwear, in good condition, is required in each class. Jewellery is not allowed, except for small pierced earrings. Students are not permitted to wear undergarments with their uniform, with the exception of bras. Bra straps must be clear or concealed and match the colour of the uniform. Students who arrive wearing clothing that does not adhere to the outlined specifications may be asked to change or observe class on that day. Please note: Students may be required to purchase an alternate colour or style of dance tights for Performance purposes. CLASS LEVEL LEOTARD, TIGHTS, SHOES & OPTIONAL DANCEWEAR Ballet Pre-School, Levels 1, 2, and 3 Pink WSD Tank or Camisole style leotard Pink dance tights, Pink ballet slippers with elastic securely sewn, Pink WSD headband Pink ballet skirt, Pink dance sweater (optional) Levels 4 & up, all Levels of Black WSD Tank or Camisole style leotard ITP & PPP Pink dance tights, Pink ballet slippers (leather or canvas) with elastic securely sewn Black ballet skirt, Black dance sweater, Black WSD headband (optional, unless otherwise specified) Levels 6 & up, Senior ITP & PPP Black WSD Faculty approved dance shorts (optional) Please note: Students enrolled in Russian Ballet Exam classes are required to wear a tank style WSD leotard (bra straps are not to be visible under any circumstance) and leather ballet slippers for -

Ballet's Influence on the Development of Early Cinema

Ballet’s Influence on the Development of Early Cinema and the Technological Modification of Dance Movement Jennifer Ann Zale Abstract Dance is a form of movement that has captured the attention of cinema spectators since the medium’s inception. The question of the compatibility between dance, particularly ballet, and cinema has been fiercely debated since the silent era and continues to be discussed by scholars and practitioners in the twenty-first century. This topic was of particular interest in the Russian cinema industry of the 1910s, in a country where ballet was considered to be among the most prestigious of the art forms. This article explores ballet’s influence on the development of silent cinema in pre-revolutionary Russia and the ways in which cinema technologies alter dance as an art form. This topic is discussed through the career of Vera Karalli, Imperial ballerina of the Bolshoi Theater turned Russia's first film star. I question the legitimacy of the argument that film can only preserve a disfigured image of a dancer’s body in motion. Many critics of Karalli’s cinematic performance fail to take into consideration the direct influence of the cinematography, editing style, and overall conditions of the Khanzhonkov Studio of 1914-1917 on the finished product. This article explores the cinematic rendition of the moving (dancing) body, taking into account the technology responsible for producing the final image. The study draws upon primary sources found in Moscow’s libraries and archives. Keywords: Dance in cinema; film history; Russian cinema; silent cinema; Vera Karalli. he final years of the Czarist era were a fruitful time period in the history of Russian ballet that included a combination of both innovative and classical choreography. -

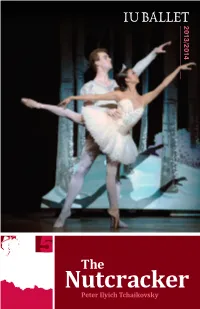

Nutcracker 5 Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season ______

2013/2014 5 The Nutcracker Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater as its 55th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffman Michael Vernon, Choreography Philip Ellis, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Design Patrick Mero, Lighting Design The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. ____________ Musical Arts Center Thursday vening,E December Fifth, Seven O’Clock Friday Evening, December Sixth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December Seventh, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December Seventh, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Eighth, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress & Children’s Ballet Mistress The children performing in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music Pre-College Ballet Program. MENAHEM PRESSLER th 90BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION Friday, Dec. 13 8pm | Musical Arts Center | $10 Students $20 Regular The Jacobs School of Music will celebrate the 90th birthday of Distinguished Professor Menahem Pressler with a concert that includes performances by violinist Daniel Hope, cellist David Finckel, pianist Wu Han, the Emerson String Quartet, and the master himself! Chat online with the legendary pianist! Thursday, Dec. 12 | 8pm music.indiana.edu/celebrate-pressler For concert tickets, visit the Musical Arts Center Box Office: (812) 855-7433, or go online to music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. -

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

May 28, 2000 Hometownnewspapers.Net 75¢ Votume 35 Numeer 103 Westland

lomeTbwn COMMUNICATIONS NETWORK lUestlanu (Dbseruer * ' » W Your hometown newspaper serving Westland for 35 years Sunday, May 28, 2000 hometownnewspapers.net 75¢ Votume 35 Numeer 103 Westland. Michigan OC000 HomeTown Communications Network™ DEAR READERS: On Thursday, June 1, a new At Home section will debut in your Chi Id's death nets 13-25 years Weatlahd Observer. The new sec tion ii a broadsheet like the Assistant Wayne County Prosecutor viction. With 18 months served, his other section* in your Home- A local man has been imprisoned for the beat Jerry Dorsey IV said. sentence means that he could be Town Observer. This means ing death of a 3-year-oid child. The boy died A defense attorney had argued after released from prison before he is 40 more local news about garden from injuries supposedly inflicted because the the boy's death that Cobb didn't mean years old. •••••*•' ing, home decorating, home child urinated on a living room floor. to hurt the toddler when he hit him for Cobb was accused of beating Darius improvement and landscaping. urinating on a living room floor. Police while the boy's mother was at wofjt. Many features that our readers described Cobb as a 6-foot-1, 275-pound Somerset compared the toddler's look forward to each week such BYDABKELLCLEM ond-degree murder, man. injuries to those he would have suf as "The Appliance Doctor" and STAFF WROTE Cobb admitted killing toddler Darius dcIein00c.hoDiecomm.net fered by falling from a two- or three- "Marketplace" continue. Deshawn Conaway by beating him The force of the blow was enough to story building. -

Bournonville À Biarritz 6Th Édition

ACADEMIE Bournonville à Biarritz 6th édition from July 28th to August 2nd 2014 Artistic director Monik Elgueta - Biarritz Artistic consultant Eric Viudes In partnership with the city of Biarritz and the Centre Chorégraphique National Malandain Ballet Biarritz Auguste Bournonville (1805-1879) Teachers Auguste Bournonville who was the son of Antoine frank andersen Bournonville, a French dancer and Director of the Royal Danish Ballet from 1985 ballet teacher who lived in exile in to 1994 and from 2002 to 2008 and of the Royal Swedish Ballet from 1995 to 1999. Danemark, studied ballet with his Professor of Dance Acedemy in Beijing father in Copenhagen before com- pleting his training in Paris with erik aschengreen Pierre Gardel and Auguste Vestris. Danish professor, dance historian and ballet He joined the Paris Opera in 1826, critic but left France in 1830 to become a principal at the Royal Danish Ballet and succeeded his father as a ballet dinna bjorn master, a post that he held until 1877. Throughout his life Director of the Norwegian National Ballet from he supported the lightness , the elegance and the phra- 1990 to 2002 and of the finnish National Ballet sing of the French balletic style. The style that he taught from 2001 to 2008, international guest teacher and that survived him thanks to an uninterrupted tradi- tion. The author of around fifty ballets essentially resting eva kloborg on a harmonious and happy vision of life, Bournonville, Character dancer at the Royal Danish Ballet and international guest teacher in spite of the way ballet changed during his lifetime, as testified by the “romantic ballet”, gave equal importance to male and female dancers. -

PRODUCTION NOTES “Flesh and Bone” Follows Claire, a Young Ballet

PRODUCTION NOTES “Flesh and Bone” follows Claire, a young ballet dancer with a distinctly troubled past, as she joins the ranks of a prestigious ballet company in New York. The gritty, complex series unflinchingly explores the dysfunction and glamour of the ballet world. Claire is a transcendent ballerina with vaulting ambitions, held back by her own self-destructive tendencies; coping mechanisms for the sexual and emotional damage she’s endured. When confronted with the machinations of the company’s mercurial Artistic Director and also an unwelcome visitor from her past, Claire’s inner torments and aspirations drive her on a compelling, unforeseeable journey. It is Moira Walley-Beckett’s first project following her Emmy-award winning tenure as a writer and Executive Producer on “Breaking Bad.” Walley-Beckett partnered with a team of Executive Producers whose backgrounds include premium programming and insider dance connections – former ballet dancer Lawrence Bender (Pulp Fiction, Inglourious Basterds, Reservoir Dogs), Kevin Brown (“Roswell”), whose family of former ballet dancers was the basis for the 1977 feature The Turning Point, and Emmy-award winning producer John Melfi, whose extensive credits include “House of Cards,” “The Comeback,” “Nurse Jackie” and the film and TV versions of “Sex and the City.” “Flesh and Bone” is a character-driven drama that “rips the Band‑Aid off the glossy, optical illusion that is ballet. Ballet appears to be ethereal and perfect - and the dancers make it look easy - but the underbelly is pain,” said Walley- Beckett. “It’s dedication. It’s obsession. It’s an addiction. And it is perfect fodder for drama.” “Ballet is the backdrop for the story and many of the characters are involved in that world, but I’m not telling a story about ballet,” Walley-Beckett explains. -

Educational Packet the Roaring 20'S

Educational Packet *BE Sure to click on the links for detailed information and Videos* The RoaRing 20’s F. Scott Fitzgerald Zelda Fitzgerald flappers The Charleston Lindy hoppers The Lindy HOp BALLET TERMINOLOGY Adagio – A dance movement done in a slow tempo. Allegro – A dance movement done in a fast tempo. Arabesque – A ballet position in which one leg is raised straight behind the body while the dancer balances on the other leg. The position has many variations, with the leg sometimes low and sometimes high, or with the leg pointed almost straight up, as in Arabesque Penchee. Attitude – A ballet position in which one leg is raised either in front of (Attitude Avant) or behind (Attitude Derriere) the body, with the knee slightly bent. Ballerina – This is a title that is given to principal or “Star” female dancers in a ballet company. Ballet – From the Italian, “Ballare,” to dance. Ballet d’Action – A dance that tells a story. Barre – The wooden rail that is attached to the walls of a dance studio for dancers to hold onto during warm-up. The barre is used to help dancers find and practice balance. Batterie – A term referring to the fast and rhythmic beating of the legs, one against the other, to add excitement to a jump. Bourees – A series of many tiny steps on points that make the dancer seem to glide across the stage. Character Dance – Folk dances that have their roots in different countries of the world. Examples: Mazurka – Polish; Czardas-Hungarian; Bolero – Spanish; Gigue – French. The term “character dance” also refers to roles that are largely mimed or comic, such as the role of Dr.