Alvin Lucier's Music for Solo Performer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice Phenomenon Electronic

Praised by Morton Feldman, courted by John Cage, bombarded with sound waves by Alvin Lucier: the unique voice of singer and composer Joan La Barbara has brought her adventures on American contemporary music’s wildest frontiers, while her own compositions and shamanistic ‘sound paintings’ place the soprano voice at the outer limits of human experience. By Julian Cowley. Photography by Mark Mahaney Electronic Joan La Barbara has been widely recognised as a so particularly identifiable with me, although they still peerless interpreter of music by major contemporary want to utilise my expertise. That’s OK. I’m willing to composers including Morton Feldman, John Cage, share my vocabulary, but I’m also willing to approach a Earle Brown, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley and her new idea and try to bring my knowledge and curiosity husband, Morton Subotnick. And she has developed to that situation, to help the composer realise herself into a genuinely distinctive composer, what she or he wants to do. In return, I’ve learnt translating rigorous explorations in the outer reaches compositional tools by apprenticing, essentially, with of the human voice into dramatic and evocative each of the composers I’ve worked with.” music. In conversation she is strikingly self-assured, Curiosity has played a consistently important role communicating something of the commitment and in La Barbara’s musical life. She was formally trained intensity of vision that have enabled her not only as a classical singer with conventional operatic roles to give definitive voice to the music of others, in view, but at the end of the 1960s her imagination but equally to establish a strong compositional was captured by unorthodox sounds emanating from identity owing no obvious debt to anyone. -

Studio Bench: the DIY Nomad and Noise Selector

Studio Bench: the DIY Nomad and Noise Selector Amit Dinesh Patel Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2019 Abstract This thesis asks questions about developing a holistic practice that could be termed ‘Studio Bench’ from what have been previously seen as three separate activities: DIY electronic instrument making, sound studio practice, and live electronics. These activities also take place in three very specific spaces. Firstly, the workshop with its workbench provides a way of making and exploring sound(- making) objects, and this workbench is considered more transient and expedient in relation to finding sounds, and the term DIY Nomad is used to describe this new practitioner. Secondly, the recording studio provides a way to carefully analyse sound(-making) objects that have been self-built and record music to play back in different contexts. Finally, live practice is used to bridge the gap between the workbench and studio, by offering another place for making and an opportunity to observe and listen to the sound(-making) object in another environment in front of a live audience. The DIY Nomad’s transient nature allows for free movement between these three spaces, finding sounds and making in a holistic fashion. Spaces are subverted. Instruments are built in the studio and recordings made on the workbench. From the nomadity of the musician, sounds are found and made quickly and intuitively, and it is through this recontextualisation that the DIY Nomad embraces appropriation, remixing, hacking and expediency. The DIY Nomad also appropriates cultures and the research is shaped through DJ practice - remixing and record selecting - noise music, and improvisation. -

Alvin Lucier's

CHAMBERS This page intentionally left blank CHAMBERS Scores by ALVIN LUCIER Interviews with the composer by DOUGLAS SIMON Wesleyan University Press Middletown, Connecticut Scores copyright © 1980 by Alvin Lucier Interviews copyright © 1980 by Alvin Lucier and Douglas Simon Several of these scores and interviews have appeared in similar or different form in Arts in Society; Big Deal; The Painted Bride Quar- terly; Parachute; Pieces 3; The Something Else Yearbook; Source Magazine; and Individuals: Post-Movement Art in America, edited by Alan Sondheim (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1977). Typography by Jill Kroesen The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of a Wesleyan University Project Grant. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lucier, Alvin. [Works. Selections] Chambers. Concrete music. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Concrete music. 2. Chance compositions. 3. Lucier, Alvin. 4. Composers—United States- Interviews. I. Simon, Douglas, 1947- II. Title. M1470.L72S5 789.9'8 79-24870 ISBN 0-8195-5042-6 Distributed by Columbia University Press 136 South Broadway, Irvington, N.Y. Printed in the United States of America First edition For Ellen Parry and Wendy Stokes This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ix 1. Chambers 1 2. Vespers 15 3. "I Am Sitting in a Room" 29 4. (Hartford) Memory Space 41 5. Quasimodo the Great Lover 53 6. Music for Solo Performer 67 7. The Duke of York 79 8. The Queen of the South and Tyndall Orchestrations 93 9. Gentle Fire 109 10. Still and Moving Lines of Silence in Families of Hyperbolas 127 11. Outlines and Bird and Person Dyning 145 12. -

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

Electronic Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kopcienski, Jacob A., "Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7493. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7493 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Thesis submitted To the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis D. -

Live Performance

LIVE PERFORMANCE LIVE PERFORMANCE AND MIDI Introduction Question: How do you perform electronic music without tape? Answer: Take away the tape. Since a great deal of early electroacoustic music was created in radio stations and since radio stations used tape recordings in broadcast, it seemed natural for electroacoustic music to have its final results on tape as well. But music, unlike radio, is traditionally presented to audiences in live performance. The ritual of performance was something that early practitioners of EA did not wish to forsake, but they also quickly realized that sitting in a darkened hall with only inanimate loudspeakers on stage would be an unsatisfactory concert experience for any audience. HISTORY The Italian composer Bruno Maderna, who later established the Milan electronic music studio with Luciano Berio, saw this limitation almost immediately, and in 1952, he created a work in the Stockhausen's Cologne studio for tape and performer. “Musica su Due Dimensioni” was, in Maderna’s words, “the first attempt to combine the past possibilities of mechanical instrumental music with the new possibilities of electronic tone generation.” Since that time, there have been vast numbers of EA works created using this same model of performer and tape. On the one hand, such works do give the audience a visual focal point and bring performance into the realm of electroacoustic music. However, the relationship between the two media is inflexible; unlike a duet between two instrumental performers, which involves complex musical compromises, the tape continues with its fixed material, regardless of the live performer’s actions. 50s + 60s 1950s and 60s Karlheinz Stockhausen was somewhat unique in the world of electroacoustic music, because he was not only a pioneering composer of EA but also a leading acoustic composer. -

It Worked Yesterday: on (Re-) Performing Electroacoustic Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Berweck, Sebastian It worked yesterday: On (re-)performing electroacoustic music Original Citation Berweck, Sebastian (2012) It worked yesterday: On (re-)performing electroacoustic music. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/17540/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ It worked yesterday On (re-)performing electroacoustic music A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sebastian Berweck, August 2012 Abstract Playing electroacoustic music raises a number of challenges for performers such as dealing with obsolete or malfunctioning technology and incomplete technical documentation. Together with the generally higher workload due to the additional technical requirements the time available for musical work is significantly reduced. -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

Sound American | SA Issue 6: Five Questions with Nicolas Collins

SOUND AMERICAN ABOUT THIS ISSUE JULIUS EASTMAN'S PRELUDE TO JOAN D'ARC + TOM JOHNSON'S RATIONAL MELODIES + GÉRARD GRISEY'S PROLOGUE TO LES ESPACE ACOUSTIQUE + ANTOINE BEUGER'S KEINE FERNEN MEHR + STEVE LACY'S DUCKS + FOUR SAXOPHONES ON BODY AND SOUL FIVE QUESTIONS: KURT GOTTSCHALK ABOUT OUR CONTRIBUTORS STORE SUBSCRIBE TO DRAM ARCHIVE OF PAST ISSUES + SA Issue 6: Five Questions with Nicolas Collins FIVE QUESTIONS WITH NICOLAS COLLINS Nic Collins: Photo by Viola Rusche New York born and raised, Nicolas Collins studied composition with Alvin Lucier at Wesleyan University, worked for many years with David Tudor, and has collaborated with numerous soloists and ensembles around the world. He lived most of the 1990s in Europe, where he was Visiting Artistic Director of Stichting STEIM (Amsterdam), and a DAAD composer-in-residence in Berlin. Since 1997 he has been editor-in-chief of the Leonardo Music Journal, and since 1999 a Professor in the Department of Sound at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His book, Handmade Electronic Music – The Art of Hardware Hacking (Routledge), has influenced emerging electronic music worldwide. Collins has the dubious distinction of having played at both CBGB and the Concertgebouw. Visit Nic at: www.nicolascollins.com ***** Five Questions with... is a feature of Sound American where I bother a very busy person until they answer a handful of queries around the issue's topic. This issue features composer, educator, and writer Nicolas Collins. Collins is best known for his ability to find music in the inner workings of everyday electronic objects. CD players become laser turntables, laptop motors create instant electronic music, and the laying of hands on circuits control unholy manipulations of children's toys. -

Sine Waves and Simple Acoustic Phenomena in Experimental Music - with Special Reference to the Work of La Monte Young and Alvin Lucier

Sine Waves and Simple Acoustic Phenomena in Experimental Music - with Special Reference to the Work of La Monte Young and Alvin Lucier Peter John Blamey Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my principal supervisor Dr Chris Fleming for his generosity, guidance, good humour and invaluable assistance in researching and writing this thesis (and also for his willingness to participate in productive digressions on just about any subject). I would also like to thank the other members of my supervisory panel - Dr Caleb Kelly and Professor Julian Knowles - for all of their encouragement and advice. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .......................................................... (Signature) Table of Contents Abstract..................................................................................................................iii Introduction: Simple sounds, simple shapes, complex notions.............................1 Signs of sines....................................................................................................................4 Acoustics, aesthetics, and transduction........................................................................6 The acoustic and the auditory......................................................................................10 -

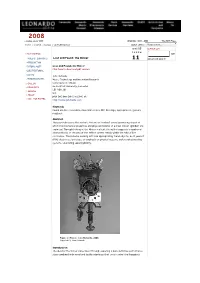

The Mincer by John Richards

22 00 00 88 -- online since 1993 ISSN NO : 1071 - 4391 The MIT Press Home > Journal > Essays > LEA-LMJ Special QUICK LINKS : Please select... vv oo l l 11 55 SEARCH LEA ii ss ss uu ee LEA E-JOURNAL GO TABLE OF CONTENTS LL oo ss t t aa nn dd FF oo uu nn dd : : t t hh ee MM i i nn cc ee r r 11 Advanced Search INTRODUCTION EDITOR'S NOTE LL oo ss t t aa nn dd FF oo uu nn dd : : t t hh ee MM i i nn cc ee r r Click here to download pdf version. GUEST EDITORIAL ESSAYS John Richards ANNOUNCEMENTS Music, Technology and Innovation Research :: GALLERY CentreSchool of Music :: RESOURCES De Montfort University, Leicester LE1 9BH, UK :: ARCHIVE U.K. :: ABOUT jrich [at] dmu [dot] ac [dot] uk :: CALL FOR PAPERS http://www.jsrichards.com KK ee yy ww oo r r dd s s Found art, live electronics, musical interface, DIY, bricolage, appropriation, gesture, feedback AA bb s s t t r r a a c c t t This paper discusses the author’s Mincer: an ‘evolved’ sound generating object of which the mechanical properties and physical material of a meat mincer (grinder) are exploited. Through looking at the Mincer in detail, the author suggests a number of characteristics of the device that reflect current trends within the field of live electronics. This includes working with and appropriating found objects, do-it-yourself (DIY) electronics, bricolage, an emphasis on physical gesture, and sound generating systems celebrating super-hybridity. -

Christian Wolff: an Aesthetic of Suggestion George E

Christian Wolff: An Aesthetic of Suggestion George E. Lewis When Christian Wolff and Robyn Schulkowsky came to my Columbia University office in October 2012 for a chat about this project, I greeted them with a YouTube video they had never seen before: a performance of the concluding work on this CD, Duo 7 from 2007. After some discussion it was determined that the video was apparently made by an audience member from a 2011 performance in Buenos Aires. “We’ve played this piece many times,” Schulkowsky laughed. “That’s a funny little piece.”1 Indeed it was, and the performance was a fortuitous introduction to a conversation that I’ve reflected upon here. Robyn Schulkowsky’s path to new music seems as fortuitous as one could imagine. Since the early 1990s she has lived in Berlin, but her musical career began in South Dakota. She applied to the Eastman School of Music, but “my parents wouldn’t let me go because it was in New York State.” So she ended up going to “new music school,” as she fondly recalled. “I wasn’t expecting anything. I didn't know anything. I just wanted to be a percussionist. I’d had maybe twenty private lessons.” But she wound up as an undergraduate at the University of Iowa, one of the most exciting scenes in the emerging American new music of the 1970s, where fellow percussionist Steven Schick was a classmate, along with the trombone-violin duo of Jon English and Candace Natvig, clarinetist Michael Lytle, percussionist Will Parsons, and the African- American electronic music composer Richard McCreary, who later taught synthesis techniques to Muhal Richard Abrams and me at Governors State University near Chicago before becoming an ordained minister.2 Moving to New Mexico, Schulkowsky teamed up with saxophonist Tom Guralnick, doing improvised music concerts and organizing a concert series that brought in Anthony Braxton and Alvin Lucier, among others—“Besides us, there was nobody doing that kind of thing there”—as well as performing with the New Mexico Symphony Orchestra and teaching at the University of New Mexico.