Preconcert Enlightenment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sales Catalog

LAUREN KEISER MUSIC PUBLISHING KEISER CLASSICAL 2014—2015 PUBLICATION CATALOG 2014—2015 PUBLICATION CATALOG TRADE/ DEALER ORDERS 1-800-554-0626 INTERNATIONAL 1-414-774-3529 ORDER ONLINE HALLEONARD.COM Lauren Keiser Music Publishing 10750 Indian Head Industrial Dr. St. Louis, MO 63132, USA 203-560-9436 * 314-270-5305 (fax) www.laurenkeisermusic.com Copyright © 2014 Lauren Keiser Music Publishing 2 CONTENTS Piano/ Keyboard....................................................................... 3 Brass....................................................................................... 18 Organ, Harpsichord & misc. ........................................ 4 Brass Ensembles ....................................................... 19 Piano ............................................................................ 3 Horn ........................................................................... 18 Vocal.......................................................................................... 4 Trombone ................................................................... 19 Baritone ........................................................................ 5 Trumpet ...................................................................... 18 Mezzo Soprano ............................................................ 4 Tuba/ Euphonium ....................................................... 19 Narrator ........................................................................ 5 Percussion Solos and Ensembles. ...................................... 20 -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Misha Amory, Viola Thomas Sauer, Piano Hsin-Yun Huang, Viola Photo by Claudio Papapietro Support Scholarships The Juilliard Scholarship Fund provides vital support to any student with need and helps make a Juilliard education possible for many deserving young actors, dancers, and musicians. With 90 percent of our students eligible for financial assistance, every scholarship gift represents important progress toward Juilliard’s goal of securing the resources required to meet the needs of our dedicated artists. Gifts in any amount are gratefully welcomed! Visit juilliard.edu/support or call Tori Brand at (212) 799-5000, ext. 692, to learn more. The Juilliard School presents Misha Amory, Viola Thomas Sauer, Piano Hsin-Yun Huang, Viola Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Friday, October 18, 2019, 7:30pm Paul Hall ZOLTÁN KODÁLY Adagio (1905) (1882-1967) FRANK BRIDGE Pensiero (1908) (1879-1941) PAUL HINDEMITH “Thema con Variationen” from Sonata, (1895-1963) Op.31, No. 4 (1922) ARTHUR BLISS “Furiant” from Viola Sonata (1934) (1891-1975) BRUCE ADOLPHE Dreamsong (1989) (b.1955) GEORGE BENJAMIN Viola, Viola (1998) (b.1960) Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by the Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation in memory of Josephine Bay Paul. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. 1 ELLIOTT CARTER Elegy (1943) (1908-2012) IGOR STRAVINSKY Elegy (1944) (1882-1971) GYÖRGY KURTÁG Jelek (1965) (b.1926) Agitato Giusto Lento Vivo Adagio Risoluto DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH “Adagio” from Viola Sonata (1975) (1906-75) Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 30 minutes, including an intermission The Viola in the 20th Century By Misha Amory The 20th century was transformative for the viola as a solo instrument. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

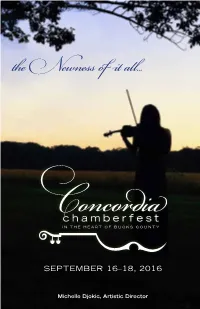

The Newness of It All

the Newness of it all... SEPTEMBER 16–18, 2016 Michelle Djokic, Artistic Director Friday,Concert September 16, 1 2016 7:00 pm The Barn at Glen Oaks Farm, Solebury, PA “Oh Gesualdo, Divine Tormentor” Bruce Adolphe SEPTEMBER for string quartet (b. 1955) 16–18, 2016 chamberfest IN THE HEART OF BUCKS COUNTY Deh, come in an sospiro Belta, poi che t'assenti Resta di darmi noia nco Gia piansi nel dolore Moro, lasso Adolphe - More or Less Momenti Clarinet Quintet in A major, K. 581 Wolfgang A. Mozart for clarinet and string quartet (1756 – 1791) THE ARTISTS Allegro Larghetto Piano - Anna Polonsky Menuetto Clarinet - Romie de Guise-Langlois Alllegretto con variazione-Adagio-Allegro Violin - Philippe Djokic, Emily Daggett-Smith Viola - Molly Carr, Juan-Miguel Hernandez Cello - Michelle Djokic k INTERMISSION k C String Quintet in C major, Opus 29 Ludwig van Beethoven for two violins, two violas and cello (1770 – 1827) Allegro moderato Adagio molto espressivo Scherzo -Allegro Presto k 1 OpenSaturday, SeptemberRehearsal 17, 2016 Sunday,Concert September 18,2 2016 10:30 am-1:00 pm & 2:00-5:00 pm 3:00 pm The Barn at Glen Oaks Farm, Solebury, PA The Barn at Glen Oaks Farm, Solebury, PA Art of the Fugue, BWV 1080 Contrapunctus I-IV Johann S. Bach Open rehearsal will feature works from for string quartet (1685 – 1750) Sunday’s program of Bach, Copland and Schumann Contrapunctus I - Allegro Contrapunctus II- Allegro moderato k Contrapunctus III - Allegro non tanto Contrapunctus IV - Allegro con brio Sextet Aaron Copland for clarinet, piano and string quartet (1900 – 1990) Allegro vivace Lento Finale k INTERMISSION k Piano Quartet in Eb Major, Opus 47 Robert Schumann for piano, violin, viola and cello (1810 – 1856) Sostenuto assai - Allegro ma non troppo Scherzo, Molto vivace Andante cantabile Finale, Vivace k For today's performance we are using a Steinway piano selected from Jacobs Music Company 2 3 PROGRAM NOTES Momenti, which consists of some of the strangest moments in Gesualdo’s music orga- nized into a mini tone-poem for string quartet. -

February 2013 Calendar of Events

FEBRUARY 2013 CALENDAR OF EVENTS For complete up-to-date information on the campus-wide performance schedule, visit www.LincolnCenter.org. Calendar information NEW YORK CITY BALLET LINCOLN CENTER PRESENTS February 3 Sunday Wheeldon/Forsythe/ AMERICAN SONGBOOK is current as of JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER Balanchine/Martins Cécile McLorin Salvant January 3, 2012 Polyphonia The Allen Room 8:30 PM René Marie Quartet with Elias Bailey, Quentin Baxter, Herman Schmerman (Pas de Deux) Kevin Bales Variations pour une Porte et un Soupir February 1 Friday LINCOLN CENTER THEATER Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola The Waltz Project Luck of the Irish 7:30 & 9:30 PM FILM SOCIETY David H. Koch Theater 8 PM OF LINCOLN CENTER A New Play by Kirsten Greenidge To view the Film Society's February NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC LINCOLN CENTER PRESENTS schedule, visit www. Filmlinc.com. Directed by Rebecca Taichman GREAT PERFORMERS Christoph von Dohnanyi, Claire Tow Theater 2 & 7 PM conductor Angelika Kirchschlager, JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER mezzo-soprano Radu Lupu, piano METROPOLITAN OPERA René Marie Quartet Beethoven: Overture to Ian Bostridge, tenor with Elias Bailey, Quentin Baxter, Le Comte Ory Julius Drake, piano The Creatures of Prometheus Metropolitan Opera House 1 PM Kevin Bales Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 Wolf: Selections from Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola Spanisches Liederbuch Beethoven Symphony No. 5 METROPOLITAN OPERA 7:30 & 9:30 PM Avery Fisher Hall 8 PM Alice Tully Hall 5 PM L'Elisir d'Amore JUILLIARD SCHOOL February 2 Saturday Metropolitan Opera House 8 PM LINCOLN CENTER THEATER David Westen, trombone Luck of the Irish Morse Hall 4 PM DAVID RUBENSTEIN ATRIUM NEW YORK CITY BALLET AT LINCOLN CENTER A New Play by Robbins/Peck/Balanchine Kirsten Greenidge JUILLIARD SCHOOL Meet the Artist Saturdays Glass Pieces Directed by Rebecca Taichman Mina Um, violin Harlem Gospel Choir Year of the Rabbit Claire Tow Theater 2 & 7 PM Paul Hall 6 PM David Rubenstein Atrium 11 AM Vienna Waltzes David H. -

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Saturday, April 18, 2015 8 p.m. 7:15 p.m. – Pre-performance discussion Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts www.quickcenter.com ~INTERMISSION~ COPLAND ................................ Two Pieces for Violin and Piano (1926) K. LEE, MCDERMOTT ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT, piano STRAVINSKY ................................Concertino for String Quartet (1920) DAVID SHIFRIN, clarinet AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, KRISTIN LEE, violin SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA AMPHION STRING QUARTET KATIE HYUN, violin DAVID SOUTHORN, violin COPLAND ............................................Sextet for Clarinet, Two Violins, WEI-YANG ANDY LIN, viola Viola, Cello, and Piano (1937) MIHAI MARICA, cello Allegro vivace Lento Finale STRAVINSKY ..................................... Suite italienne for Cello and Piano SHIFRIN, HYUN, SOUTHORN, Introduzione: Allegro moderato LIN, MARICA, MCDERMOTT Serenata: Larghetto Aria: Allegro alla breve Tarantella: Vivace Please turn off cell phones, beepers, and other electronic devices. Menuetto e Finale Photographing, sound recording, or videotaping this performance is prohibited. MARICA, MCDERMOTT COPLAND ...............................Two Pieces for String Quartet (1923-28) AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA STRAVINSKY ............................Suite from Histoire du soldat for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano (1918-19) The Soldier’s March Music to Scene I Music to Scene II Tonight’s performance is sponsored, in part, by: The Royal March The Little Concert Three Dances: Tango–Waltz–Ragtime The Devil’s Dance Great Choral Triumphal March of the Devil K. LEE, SHIFRIN, MCDERMOTT Notes on the Program by DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Two Pieces for String Quartet Aaron Copland Suite italienne for Cello and Piano Born November 14, 1900 in Brooklyn, New York. Igor Stravinsky Died December 2, 1990 in North Tarrytown, New York. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

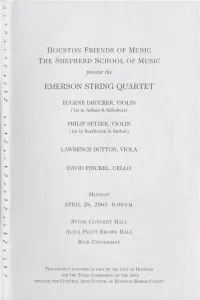

Emerson String Quartet

HOUSTON FRIENDS OF MUSIC THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC present the EMERSON STRING QUARTET EUGENE DRUCKER, VIOLIN (1st in Aitken & Schubert) PHILIP SETZER, VIOLIN (1st in Beethoven & Barber) .. LAWRENCE DUTTON, VIOLA DAVID FINCKEL, CELLO MONDAY -,. APRIL 28, 2003 8:00 P.M. STUDE CONCERT HALL ALICE PRATT BROWN HALL RICE UNIVERSITY THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED IN PART BY THE CITY OF HOUSTON AND TIIE T EXAS COMMISSION ON THE ARTS THROUGH THE CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL OF HOUSTON/HARRIS COUNTY. EMERSON STRING QUARTET -PROGRAM- LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro HUGH AITKEN (b.1924) Laura Goes to India (1998) SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) A . Adagio for String Quartet, Op. 11 (1936) -INTERMISSION- FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Quartet in D Minor, D. 810, "Death and the Maiden" (1824) Allegro Andante con moto Scherzo: Allegro molto Presto -.. The Emerson String Quartet appears by arrangement with IMC Artists and records exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. www.emersonquartet.com LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) ·.1 Beethoven wrote the Opus 18 Quartets during his first years in Vienna. He had arrived from Germany in 1792 by permission of the Elector of Bonn, shortly before his twenty-second birthday, in high spirits and carrying with him introductions to some of the most prominent members of music-loving Viennese nobility, who welcomed him into their substantial musical lives. At the end of his first four years in Vienna he had established himself as a pianist of major importance and a composer of the utmost promise; he had published, among other things, a set of three Piano Trios, Op.l, three Trios for Strings, Op. -

I Will Not Remain Silent: New Milken Archive of Jewish Music Album by Composer Bruce Adolphe Speaks to Past, Present, Future

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: [email protected] January 19, 2021 (310) 570-4770 I Will Not Remain Silent: New Milken Archive of Jewish Music Album By Composer Bruce Adolphe Speaks to Past, Present, Future “The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence.”—Rabbi Joaquim Prinz, 1963 With themes central to our times, the Milken Archive of Jewish Music: The American Experience is releasing its first new album since 2015 with I Will Not Remain Silent, by prominent American composer Bruce Adolphe. Featuring two compositions, the album explores themes of social justice through the prism of 20th-century activist Rabbi Joachim Prinz. Born in 1902, Prinz spoke out against the rise of anti-Semitism as a rabbi in Germany in the 1920s and 30s and became a prominent voice of the American Civil Rights Movement. Though not as well-known today, Prinz's public profile was such that he preceded Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at the 1963 March on Washington, where King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Prinz used this highly visible, national platform to stress the importance of speaking out against hatred and bigotry, and to emphasize the dangers of silence. “When I was the rabbi of the Jewish community in Berlin under the Hitler regime, I learned many things,” Prinz told the crowd assembled that day in 1963. “The most important thing that I learned under those tragic circumstances was that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problem. The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence.” In focusing on silence as the most important problem of the American Civil Rights Movement, Prinz emphasized the responsibility that those not affected by racism and inequality have in creating a more just and equal society. -

~ 1 ~ I Will Not Remain Silent: New Milken Archive of Jewish Music Album by Composer Bruce Adolphe Speaks to Past, Present, Futu

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: [email protected] January 19, 2021 (310) 570-4770 FOR MEDIA ONLY: Album Tracks/Photos/Video I Will Not Remain Silent: New Milken Archive of Jewish Music Album By Composer Bruce Adolphe Speaks to Past, Present, Future “The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence.”—Rabbi Joaquim Prinz, 1963 With themes central to our times, the Milken Archive of Jewish Music: The American Experience is releasing its first new album since 2015 with I Will Not Remain Silent, by prominent American composer Bruce Adolphe. Featuring two compositions, the album explores themes of social justice through the prism of 20th-century activist Rabbi Joachim Prinz. “The Milken Archive release of I Will Not Remain Silent and Reach Out, Raise Hope, Change Society brings together two very different works about violence, injustice, human rights, and hope at a moment when there is an urgent need once again for this message to be powerfully sounded in America,” said Adolphe. “I appreciate that the Milken Archive recognizes the significance of these works and the importance of Prinz’s message.” Born in 1902, Prinz spoke out against the rise of anti-Semitism as a rabbi in Germany in the 1920s and 30s and became a prominent voice of the American Civil Rights Movement. Though not as well-known today, Prinz's public profile was such that he preceded Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at the 1963 March on Washington, where King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Prinz used this highly visible, national platform to stress the importance of speaking out against hatred and bigotry, and to emphasize the dangers of silence. -

BRENTANO QUARTET Mark Steinberg, Violin Serena Canin, Violin Misha Amory, Viola Nina Lee, Cello

BRENTANO QUARTET Mark Steinberg, violin Serena Canin, violin Misha Amory, viola Nina Lee, cello Sunday, October 18 – 3:00 PM Benjamin Franklin Hall, American Philosophical Society This concert is supported in part by Robert E. Mortensen. PROGRAM FELIX MENDELSSOHN JOHANNES BRAHMS Four Pieces for String Quartet, Op. 81 [Sel.] String Quartet in A Minor, Op. 51, No. 2 Tema con variazioni: Andante sostenuto Allegro non troppo Scherzo: Allegro leggiero Andante moderato Quasi minuetto, moderato ROBERT SCHUMANN Finale: Allegro non assai String Quartet in A Major, Op. 41, No. 3 Andante espressivo—Allegro molto moderato Assai agitato Adagio molto Allegro molto vivace—Quasi Trio ABOUT THE BRENTANO QUARTET Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and critical acclaim. “Passionate, uninhibited and spellbinding,” raves the London Independent; the New York Times extols its “luxuriously warm sound [and] yearning lyricism.” Within a few years of its formation, the Quartet garnered the first Cleveland Quartet Award and the Naumburg Chamber Music Award and was also honored in the UK with the Royal Philharmonic Award for Most Outstanding Debut. Since then, the Quartet has concertized widely, performing in the world’s most prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall in New York; the Library of Congress in Washington; the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam; the Konzerthaus in Vienna; Suntory Hall in Tokyo; and the Sydney Opera House. In addition to performing the entire two-century range of the standard quartet repertoire, the Brentano Quartet maintains a strong interest in contemporary music, and has commissioned many new works. Their latest project, a monodrama for quartet and voice called Dido Reimagined, was composed by Pulitzer- winning composer Melinda Wagner and librettist Stephanie Fleischmann, and will premiere in spring 2021 with soprano Dawn Upshaw. -

MUSICIAN BIOGRAPHIES Bernard Mindich Bernard Lisa-Marie Mazzucco

CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE ONSTAGE ANI KAVAFIAN, violin Bernard Mindich DAVID SHIFRIN, clarinet MIHAI MARICA, cello , viola TARA HELEN O’CONNOR, flute PAUL NEUBAUER YURA LEE, viola Lisa-Marie Mazzucco Bernard Mindich Lisa-Marie Mazzucco ARNAUD SUSSMANN, violin © 2007 NyghtFalcon All Rights Reserved Today’s performance is sponsored by Tom and Mary Ellen Litzinger COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL The Community Advisory Council is dedicated to strengthening the relationship between the Center for the Performing Arts and the community. Council members participate in a range of activities in support of this objective. Nancy VanLandingham, chair Mary Ellen Litzinger Lam Hood, vice chair Bonnie Marshall Pieter Ouwehand William Asbury Melinda Stearns Patricia Best Susan Steinberg Lynn Sidehamer Brown Lillian Upcraft Philip Burlingame Pat Williams Alfred Jones Jr. Nina Woskob Deb Latta Eileen Leibowitz student representative Ellie Lewis Jesse Scott Christine Lichtig CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE presents The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Tara Helen O’Connor, flute David Shifrin, clarinet Ani Kavafian, violin Arnaud Sussmann, violin Yura Lee, viola Paul Neubauer, viola Mihai Marica, cello 7:30 p.m. Thursday, November 20, 2014 Schwab Auditorium The performance includes one intermission. This presentation is a component of the Center for the Performing Arts Classical Music Project. With support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the project provides opportunities to engage students, faculty, and the community with classical music artists and programs. Marica Tacconi, Penn State professor of musicology, and Carrie Jackson, Penn State associate professor of German and linguistics, provide faculty leadership for the curriculum and academic components of the grant project.