Choosing to Make Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell Crosby’s 1945 holiday album Original release label “Holiday Inn” movie poster With the possible exception of “Silent Night,” no other song is more identified with the holiday season than “White Christmas.” And no singer is more identified with it than its originator, Bing Crosby. And, perhaps, rightfully so. Surely no other Christmas tune has ever had the commercial or cultural impact as this song or sold as many copies--50 million by most estimates, making it the best-selling record in history. Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas” in 1940. Legends differ as to where and how though. Some say he wrote it poolside at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona, a reasonable theory considering the song’s wishing for wintery weather. Some though say that’s just a good story. Furthermore, some histories say Berlin knew from the beginning that the song was going to be a massive hit but another account says when he brought it to producer-director Mark Sandrich, Berlin unassumingly described it as only “an amusing little number.” Likewise, Bing Crosby himself is said to have found the song only merely adequate at first. Regardless, everyone agrees that it was in 1942, when Sandrich was readying a Christmas- themed motion picture “Holiday Inn,” that the song made its debut. The film starred Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby and it needed a holiday song to be sung by Crosby and his leading lady, Marjorie Reynolds (whose vocals were dubbed). Enter “White Christmas.” Though the film would not be seen for many months, millions of Americans got to hear it on Christmas night, 1941, when Crosby sang it alone on his top-rated radio show “The Kraft Music Hall.” On May 29, 1942, he recorded it during the sessions for the “Holiday Inn” album issued that year. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Biu Withers by Rob Bowman He Was the Leading Figure in the Nascent Black Singer-Songwriter Movement of the Early 1970S

PERFORMERS BiU Withers By Rob Bowman He was the leading figure in the nascent black singer-songwriter movement of the early 1970s. BILL WITHERS WAS SIMPLY NOT BORN TO PLAY THE record industry game. His oft-repeated descriptor for A&R men is “antagonistic and redundant.” Not surprisingly, most A&R men at Columbia Records, the label he recorded for beginning in 1975, considered him “difficult.” Yet when given the freedom to follow his muse, Withers wrote, sang, and in many cases produced some of our most enduring classics, including “Ain’t No Sunshine,” “Lean on Me,” “Use Me,” “Lovely Day,” “Grandma’s Hands,” and “Who Is He (and What Is He to You).” ^ “Not a lot of people got me,” Withers recently mused. “Here I was, this black guy playing an acoustic guitar, and I wasn’t playing the gut-bucket blues. People had a certain slot that they expected you to fit in to.” ^ Withers’ story is about as improb able as it could get. His first hit, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” recorded in 1971 when he was 33, broke nearly every pop music rule. Instead of writing words for a bridge, Withers audaciously repeated “I know” twenty-six times in a row. Moreover, the two-minute song had no introduction and was released as a throwaway B-side. Produced by Stax alumni Booker T. Jones for Sussex Records, the single’s struc ture, sound, and sentiment were completely unprecedented and pos sessed a melody and lyric that tapped into the Zeitgeist of the era. Like much of Withers’ work, it would ultimately prove to be timeless. -

Best-Selling American Instrumental Artist & Grammy Award® Winner Chris Botti Performs at the Kimmel Center Campus May 6, 2017

Tweet it! Grammy-winning trumpeter @ChrisBotti performs swoon-worthy songs from his most recent album #Impressions at @KimmelCenter for one night only 5/6 Press Contact: Amanda Conte 215-790-5847 [email protected] BEST-SELLING AMERICAN INSTRUMENTAL ARTIST & GRAMMY AWARD® WINNER CHRIS BOTTI PERFORMS AT THE KIMMEL CENTER CAMPUS MAY 6, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, March 23, 2017) –– The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, in association with BRE Presents, welcomes Grammy Award® winner and largest-selling American instrumental artist Chris Botti to the Merriam Theater for one night only on Saturday, May 6, 2017 at 8:00 p.m. Using creative expression to push the limits of any single genre, Botti will perform compositions from his repertoire of 10 studio albums, including his most recent album Impressions, which took home the 2013 Grammy Award® for Best Pop Instrumental Album. “Chris Botti is one of the most innovative and celebrated figures of the modern music era,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “His ability to flawlessly move from genre to genre shines through in his meticulously crafted performance, creating timeless arrangements that will leave music lovers of all ages in awe.” Over the past three decades, Botti has recorded and performed with some of the most iconic names in music, including Sting, Barbra Streisand, Tony Bennett, Lady Gaga, Josh Groban, Yo-Yo Ma, Michael Bublé, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, John Mayer, Andrea Bocelli, Joshua Bell, Aerosmith's Steven Tyler, and even Frank Sinatra. Hitting the road for as many as 300 days per year, the trumpeter has performed with some of the finest symphonies and at some of the world's most prestigious venues, from Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl to the Sydney Opera House and the Real Teatro di San Carlo in Italy. -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

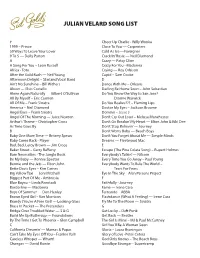

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

News Archives the Buffalo News

News Archives: The Buffalo News http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_action=doc&p_d... BuffaloNews.com Buffalo.com Mobile Sitemap ShopBuffalo Marketplace Jobs Cars Real Estate Rentals Classifieds ADVERTISER INDEX ADVERTISEMENT Forecast 62° Traffic City & Region Sports Entertainment Life Business Opinion Deaths Multimedia Reader Services The Buffalo News Archives Hamlisch, Klein, Arnaz prove irresistible Published on April 20, 2008 Author: Mary Kunz Goldman - NEWS CLASSICAL MUSIC CRITIC © The Buffalo News Inc. The best part of the mini-version of "They're Playing Our Song," the climax of Saturday's pops concert in Kleinhans Music Hall, was watching the back of Marvin Hamlisch's head. That was because comedian Robert Klein, in his irresistible yappy way, reminded us how the show, which was a success on Broadway a couple of decades ago, was based on Hamlisch's own romance with Carole Bayer Sager. So as we heard the songs from the show, it was hard not to look at Hamlisch, and think: This is all about him! What can it feel like, having your own personal feelings laid bare for this big sold-out Buffalo audience to see? Hamlisch, planted on the podium solid as an ox, didn't seem to mind. But still. The night was full of various kinds of drama. Klein got about 20 minutes to himself for stand-up comedy and song, and it was great fun, even if it was geared frankly toward an older crowd. His opening song, about colonoscopies, brought the house down. Lucie Arnaz, the daughter of Lucille Ball, was also endearing. -

Dream Shake Song List

Dream Shake Song List My Stupid Mouth – John Mayer Nature Boy – Nat King Cole Africa – D’angelo On & On – Erykah Badu Aint No Sunshine – Bill Withers One Mo Gin’ – D’angelo Back in the Day – Erykah Badu Ordinary People – John Legend Banana Pancakes – Jack Johnson Roses – Outkast Brown Sugar – D’angelo Save Room – John Legend City Love – John Mayer Senorita – Justin Timberlake Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Seven Nation Army – White Stripes (Ben l Oncle Cruisin’ – D’angelo Soul) Don’t Worry Be Happy – Bobby Mcferrin Sitting, Waiting, Wishing – Jack Johnson Easy Like Sunday Morning – Lionel Richie Slow Dancing – John Mayer Fallin’ – Alicia Keys Stay With You – John Legend Feel Like Making Love – Roberta Flack (D’angelo) Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Georgia On My Mind – Ray Charles Sunday Morning – Maroon 5 Get Lucky – Daft Punk Sunny – Bobby Hebb Got to Give it up – Marvin Gaye Super Rich Kids – Frank Ocean Gravity – John Mayer Taylor – Jack Johnson Hey Ya – Outkast Thinkin Bout You - Frank Ocean Hit the Road Jack – Ray Charles Vallery – Amy Winehouse I Need a Dollar – Aloe Black Waiting in Vain – Bob Marley I Shot the Sheriff – Bob Marley What’s Going On – Marvin Gaye Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder When We get By – D’angelo Just Friends – Musiq Soulchild Why Georgia – John Mayer Lazy Song – Bruno Mars Wonderful World – Louis Armstrong Lean On Me – Bill Withers Your Body is a Wonderland – John Mayer Lovely Day – Bill Withers And many more… Man’s World – James Brown Mercy Mercy Me – Marvin Gaye Ms. Jackson – Outkast . -

Press Release: for Immediate Release

PRESS RELEASE: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Mike Michelon, Executive Director 734-994-5899, [email protected] #### Ann Arbor Summer Festival Announces First Shows of the Season ANN ARBOR MI (February 12, 2020) – The Ann Arbor Summer Festival is pleased to announce three headlining ticketed performances for the festival’s 2020 season. Festival Executive Director Mike Michelon shares, “We are thrilled to announce three of our ticketed shows early this season. Our 37th season will feature an eclectic mix of a Broadway icon, a world class illusionist, and an infamous comedy troupe returning for their 21st season.” The remaining ticketed performances will be announced in March. The full Top of the Park season will be announced on May 1. Festival Ticket Information Tickets On Sale: Thursday, February 13 at 9 am (General Public) Online: tickets.a2sf.org By Phone: (734) 764-2538 or toll-free in Michigan at (800) 221-1229 In Person: Michigan League Ticket Office, 911 N. University Ave, Ann Arbor MI 48109 Festival Venue Information Power Center for the Performing Arts: 121 Fletcher Street, Ann Arbor, MI Hill Auditorium: 825 N University Ave, Ann Arbor, MI Zingerman’s Greyline: 100 N Ashley St, Ann Arbor, MI Top of the Park: 915 E Washington St, Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor Summer Festival 2020 Ticketed Performances Scott Silven: Wonders at Dusk Wednesday-Friday, June 24-26 at 6:30/7pm Zingerman’s Greyline $55 (plus fees), $35 (plus fees), ages 12-18 Scott Silven is an incomparable modern marvel, and he returns to A2SF after a sold-out run in 2018. -

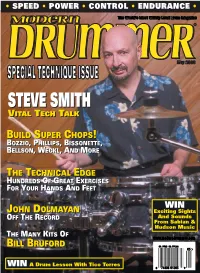

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

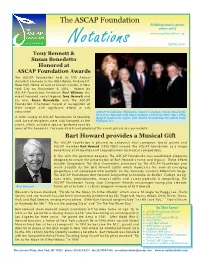

Notations Spring 2011

The ASCAP Foundation Making music grow since 1975 www.ascapfoundation.org Notations Spring 2011 Tony Bennett & Susan Benedetto Honored at ASCAP Foundation Awards The ASCAP Foundation held its 15th Annual Awards Ceremony at the Allen Room, Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York City on December 8, 2010. Hosted by ASCAP Foundation President, Paul Williams, the event honored vocal legend Tony Bennett and his wife, Susan Benedetto, with The ASCAP Foundation Champion Award in recognition of their unique and significant efforts in arts education. ASCAP Foundation Champion Award recipients Susan Benedetto (l) & Tony Bennett with Mary Rodgers (2nd from left), Mary Ellin A wide variety of ASCAP Foundation Scholarship Barrett (2nd from right), and ASCAP Foundation President Paul and Award recipients were also honored at the Williams (r). event, which included special performances by some of the honorees. For more details and photos of the event, please see our website. Bart Howard provides a Musical Gift The ASCAP Foundation is pleased to announce that composer, lyricist, pianist and ASCAP member Bart Howard (1915-2004) named The ASCAP Foundation as a major beneficiary of all royalties and copyrights from his musical compositions. In line with this generous bequest, The ASCAP Foundation has established programs designed to ensure the preservation of Bart Howard’s name and legacy. These efforts include: Songwriters: The Next Generation, presented by The ASCAP Foundation and made possible by the Bart Howard Estate which showcases the work of emerging songwriters and composers who perform on the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage. The ASCAP Foundation Bart Howard Songwriting Scholarship at Berklee College recog- nizes talent, professionalism, musical ability and career potential in songwriting.