From Cato Manor to Kwa Mashu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa

Safrica Page 1 of 42 Recent Reports Support HRW About HRW Site Map May 1995 Vol. 7, No.3 SOUTH AFRICA THREATS TO A NEW DEMOCRACY Continuing Violence in KwaZulu-Natal INTRODUCTION For the last decade South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal region has been troubled by political violence. This conflict escalated during the four years of negotiations for a transition to democratic rule, and reached the status of a virtual civil war in the last months before the national elections of April 1994, significantly disrupting the election process. Although the first year of democratic government in South Africa has led to a decrease in the monthly death toll, the figures remain high enough to threaten the process of national reconstruction. In particular, violence may prevent the establishment of democratic local government structures in KwaZulu-Natal following further elections scheduled to be held on November 1, 1995. The basis of this violence remains the conflict between the African National Congress (ANC), now the leading party in the Government of National Unity, and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), the majority party within the new region of KwaZulu-Natal that replaced the former white province of Natal and the black homeland of KwaZulu. Although the IFP abandoned a boycott of the negotiations process and election campaign in order to participate in the April 1994 poll, following last minute concessions to its position, neither this decision nor the election itself finally resolved the points at issue. While the ANC has argued during the year since the election that the final constitutional arrangements for South Africa should include a relatively centralized government and the introduction of elected government structures at all levels, the IFP has maintained instead that South Africa's regions should form a federal system, and that the colonial tribal government structures should remain in place in the former homelands. -

List of Outstanding Trc Beneficiaries

List of outstanding tRC benefiCiaRies JustiCe inVites tRC benefiCiaRies to CLaiM tHeiR finanCiaL RePaRations The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development invites individuals, who were declared eligible for reparation during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission(TRC), to claim their once-off payment of R30 000. These payments will be eff ected from the President Fund, which was established in accordance with the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act and regulations outlined by the President. According to the regulations the payment of the fi nal reparation is limited to persons who appeared before or made statements to the TRC and were declared eligible for reparations. It is important to note that as this process has been concluded, new applications will not be considered. In instance where the listed benefi ciary is deceased, the rightful next-of-kin are invited to apply for payment. In these cases, benefi ciaries should be aware that their relationship would need to be verifi ed to avoid unlawful payments. This call is part of government’s attempt to implement the approved TRC recommendations relating to the reparations of victims, which includes these once-off payments, medical benefi ts and other forms of social assistance, establishment of a task team to investigate the nearly 500 cases of missing persons and the prevention of future gross human rights violations and promotion of a fi rm human rights culture. In order to eff ectively implement these recommendations, the government established a dedicated TRC Unit in the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development which is intended to expedite the identifi cation and payment of suitable benefi ciaries. -

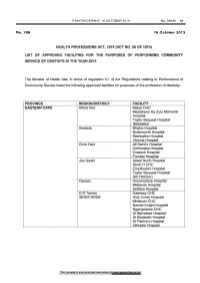

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes of Performing Community Service by Dentists in the Year

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 13 No. 788 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY DENTISTS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of dentistry. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Maluti CHC Madzikane Ka Zulu Memorial Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Matatiele) Amato le Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Madwaleni Hospital Victoria Hospital Chris Hani All Saint's Hospital Cofimvaba Hospital Cradock Hospital Frontier Hospital Joe Gqabi Aliwal North Hospital Block H CHC Empilisweni Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Mt Fletcher) Cacadu Humansdorp Hospital Midlands Hospital Settlers Hospital O.R Tambo Gateway CHC ISRDS NODE Holy Cross Hospital Mhlakulo CHC Nessie Knight Hospital Ngangelizwe CHC St Barnabas Hospital St Elizabeth Hospital St Patrick's Hospital Zithulele Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 14 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 FREE STATE Motheo District(DC17) National Dental Clinic Botshabelo District Hospital Fezile Dabi District(DC20) Kroonstad Dental Clinic MafubefTokollo Hospital Complex Metsimaholo/Parys Hospital Complex Lejweleputswa DistrictWelkom Clinic Area(DC18) Thabo Mofutsanyana District Elizabeth Ross District Hospital* (DC19) Itemoheng Hospital* ISRDS NODE Mantsopa -

Ungovernability and Material Life in Urban South Africa

“WHERE THERE IS FIRE, THERE IS POLITICS”: Ungovernability and Material Life in Urban South Africa KERRY RYAN CHANCE Harvard University Together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches . we shall liberate this country. —Winnie Mandela, 1986 Faku and I stood surrounded by billowing smoke. In the shack settlement of Slovo Road,1 on the outskirts of the South African port city of Durban, flames flickered between piles of debris, which the day before had been wood-plank and plastic tarpaulin walls. The conflagration began early in the morning. Within hours, before the arrival of fire trucks or ambulances, the two thousand house- holds that comprised the settlement as we knew it had burnt to the ground. On a hillcrest in Slovo, Abahlali baseMjondolo (an isiZulu phrase meaning “residents of the shacks”) was gathered in a mass meeting. Slovo was a founding settlement of Abahlali, a leading poor people’s movement that emerged from a burning road blockade during protests in 2005. In part, the meeting was to mourn. Five people had been found dead that day in the remains, including Faku’s neighbor. “Where there is fire, there is politics,” Faku said to me. This fire, like others before, had been covered by the local press and radio, some journalists having been notified by Abahlali via text message and online press release. The Red Cross soon set up a makeshift soup kitchen, and the city government provided emergency shelter in the form of a large, brightly striped communal tent. Residents, meanwhile, CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 30, Issue 3, pp. 394–423, ISSN 0886-7356, online ISSN 1548-1360. -

CLIMATE ACTION PLAN? 8 the Global Shift to 1.5°C 8 Cities Taking Bold Action 9

ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING & CLIMATE PROTECTION DEPARTMENT CLIMATE PROTECTION BRANCH 166 KE Masinga (Old Fort) Road, Durban P O Box 680, Durban, 4000 Tel: 031 311 7920 ENERGY OFFICE 3rd Floor, SmartXchange 5 Walnut Road, Durban, 4001 Tel: 031 311 4509 www.durban.gov.za Design and layout by ARTWORKS | www.artworks.co.za ii Table of Contents Message from the Mayor 2 Message from C40 Cities Regional Director for Africa 3 Preamble 4 1 DURBAN AS A CITY 5 2 WHY A 1.5°C CLIMATE ACTION PLAN? 8 The global shift to 1.5°C 8 Cities taking bold action 9 3 A SNAPSHOT OF DURBAN’S CLIMATE CHANGE JOURNEY 12 4 CLIMATE CHANGE GOVERNANCE IN DURBAN 14 Existing governance structures 14 Opportunities for climate governance 14 Pathways to strengthen climate governance 16 5 TOWARDS A CARBON NEUTRAL AND A RESILIENT DURBAN 18 Durban’s GHG emissions 18 Adapting to a changing climate 22 6 VISION AND TARGETS 28 7 ACTIONS 30 Securing carbon neutral energy for all 34 Moving towards clean, efficient and affordable transport 38 Striving towards zero waste 42 Providing sustainable water services and protection from flooding 45 Prioritising the health of communities in the face of a changing climate 51 Protecting Durban’s biodiversity to build climate resilience 54 Provide a robust and resilient food system for Durban 57 Protecting our City from sea-level rise 60 Building resilience in the City’s vulnerable communities 63 8 ACTION TIMEFRAME AND SUMMARY TABLE 66 9 SISONKE: TOGETHER WE CAN 73 Responding to the challenge 73 Together we can 75 10 FINANCING THE TRANSITION 78 11 MONITORING AND UPDATING THE CAP 80 Existing structures 80 Developing a CAP Monitoring and Evaluation Framework 80 List of acronyms 82 Endnotes 84 Durban Climate Action Plan 2019 1 Message from the Mayor limate change is one of the most pressing challenges of our time. -

Community Struggle from Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Jacob, "Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 404. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/404 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS DELIVERY AND DIGNITY: COMMUNITY STRUGGLE FROM KENNEDY ROAD Jacob Bryant Richard Pithouse, Center for Civil Society School for International Training South Africa: Reconciliation and Development Fall 2005 “The struggle versus apartheid has been a little bit achieved, though not yet, not in the right way. That’s why we’re still in the struggle, to make sure things are done right. We’re still on the road, we’re still grieving for something to be achieved, we’re still struggling for more.” -- Sbusiso Vincent Mzimela “The ANC said ‘a better life for all,’ but I don’t know, it’s not a better life for all, especially if you live in the shacks. We waited for the promises from 1994, up to 2004, that’s 10 years of waiting for the promises from the government. -

Know Your Vaccination Sites for Phase 2:Week 26 July -01 August 2021 Sub-Distrct Facility/Site Ward Address Operating Days Operating Hours

UTHUKELA HEALTH DISTRICT VACCINATION SITES FOR THE WEEK 26-31 JULY 2021 SUB- FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS DISTRCT Inkosi ThusongKNOWHall YOUR14 Next to oldVACCINATION Mbabazane 26 - 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Ntabamhlope Municipal offices Inkosi Weenen Comm Hall 20 Next to municipal offices 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele SITES Inkosi Wembezi Hall 9 VQ Section 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Inkosi Forderville Hall 10 Canna Avenue 26-30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Fordeville Inkosi Mahlutshini Hall 12 Next to Mahlutshini Tribal 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele Court Inkosi Phasiwe Hall 6 Next to Phasiwe Primary 26- 30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele School Inkosi Estcourt hospital 23 No. 1 Old main Road, 26-30 July 2021 08:00 – 16:00 Langalibalele southwing nurses home Estcourt UTHUKELA HEALTH DISTRICT VACCINATION SITES FOR THE WEEK 26-31 JULY 2021 SUB- FACILITY/SITE WARD ADDRESS OPERATING DAYS OPERATING HOURS DISTRCT Inkosilangali MoyeniKNOWHall 2 YOURLoskop Area -VACCINATIONnext to Mjwayeli P 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele School Inkosilangali Geza Hall 5 Next to Jafter Store – Loskop 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele Area SITES Inkosilangali Mpophomeni Hall 1 Loskop Area at Ngodini 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele Inkosilangali Mdwebu Methodist 14 Ntabamhlophe Area- Next to 31 Jul- 01 Aug 08:00 – 16:00 balele Church Mdwebu Hall 2021 Inkosilangali Thwathwa Hall 13 Kwandaba Area at 31 Jul-01 Aug 2021 08:00 – 16:00 balele -

Final Basic Assessment Report

FINAL BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT FINAL BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT PROPOSED BRIDGE CITY BP SERVICE STATION, SITUATED ON PORTION 151 OF ERF 8, BRIDGE CITY, KWAMASHU, WITHIN ETHEKWINI METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY, KWAZULU-NATAL Submitted in terms of the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, 2014 promulgated in terms of the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998) EDTEA File Reference Number: DM/0028/2016 HANSLAB (PTY) LTD BRIDGE CITY BP SERVICE STATION Page 1 FINAL BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT DOCUMENT NAME Final Basic Assessment Report APPLICANT Hlengwa & Zulu Investments (Pty) Ltd The Proposed BP Service Station Development, situated PROJECT NAME on Portion 151 of Erf 8, Bridge City, KwaMashu, within the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, KwaZulu Natal. ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PRACTITIONER’S ORGANISATION Hanslab (Pty) Ltd DM/0028/2016 EDTEA FILE REFERENCE NUMBER LOCATION Durban – KwaZulu Natal COMPILED BY: Ms. Jashmika Maharaj SIGNATURE: _________________________ REVIEWED BY: Mr. Sheldon Singh SIGNATURE: ___________________________ DATE: 09 December 2016 HANSLAB (PTY) LTD BRIDGE CITY BP SERVICE STATION Page 2 FINAL BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT REVIEW OF THE FINAL BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT This Final Basic Assessment Report is available for commenting for a period of 30 days (excluding Public Holidays) from Monday, 12 December 2016 until Monday, 06 February 2017. A copy of the Final Basic Assessment Report is available at strategic public place in the project area and upon request from Afzelia Environmental Consultants (Pty) Ltd. The report is available for viewing at the following library: Bester Community Library, Next to the Bester Community Hall, 20 Dalmeny Main Road, Q-Section KwaMashu, The report is also available for viewing on the Afzelia website: www.afzelia.co.za Please forward any further comments to Ms Adika Rambally at the Department of Economic Development, Tourism & Environment Affairs by post, fax or email at the contact details below. -

Ward Councillors Pr Councillors Executive Committee

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE KNOW YOUR CLLR WEZIWE THUSI CLLR SIBONGISENI MKHIZE CLLR NTOKOZO SIBIYA CLLR SIPHO KAUNDA CLLR NOMPUMELELO SITHOLE Speaker, Ex Officio Chief Whip, Ex Officio Chairperson of the Community Chairperson of the Economic Chairperson of the Governance & COUNCILLORS Services Committee Development & Planning Committee Human Resources Committee 2016-2021 MXOLISI KAUNDA BELINDA SCOTT CLLR THANDUXOLO SABELO CLLR THABANI MTHETHWA CLLR YOGISWARIE CLLR NICOLE GRAHAM CLLR MDUDUZI NKOSI Mayor & Chairperson of the Deputy Mayor and Chairperson of the Chairperson of the Human Member of Executive Committee GOVENDER Member of Executive Committee Member of Executive Committee Executive Committee Finance, Security & Emergency Committee Settlements and Infrastructure Member of Executive Committee Committee WARD COUNCILLORS PR COUNCILLORS GUMEDE THEMBELANI RICHMAN MDLALOSE SEBASTIAN MLUNGISI NAIDOO JANE PILLAY KANNAGAMBA RANI MKHIZE BONGUMUSA ANTHONY NALA XOLANI KHUBONI JOSEPH SIMON MBELE ABEGAIL MAKHOSI MJADU MBANGENI BHEKISISA 078 721 6547 079 424 6376 078 154 9193 083 976 3089 078 121 5642 WARD 01 ANC 060 452 5144 WARD 23 DA 084 486 2369 WARD 45 ANC 062 165 9574 WARD 67 ANC 082 868 5871 WARD 89 IFP PR-TA PR-DA PR-IFP PR-DA Areas: Ebhobhonono, Nonoti, Msunduzi, Siweni, Ntukuso, Cato Ridge, Denge, Areas: Reservoir Hills, Palmiet, Westville SP, Areas: Lindelani C, Ezikhalini, Ntuzuma F, Ntuzuma B, Areas: Golokodo SP, Emakhazini, Izwelisha, KwaHlongwa, Emansomini Areas: Umlazi T, Malukazi SP, PR-EFF Uthweba, Ximba ALLY MOHAMMED AHMED GUMEDE ZANDILE RUTH THELMA MFUSI THULILE PATRICIA NAIR MARLAINE PILLAY PATRICK MKHIZE MAXWELL MVIKELWA MNGADI SIFISO BRAVEMAN NCAYIYANA PRUDENCE LINDIWE SNYMAN AUBREY DESMOND BRIJMOHAN SUNIL 083 7860 337 083 689 9394 060 908 7033 072 692 8963 / 083 797 9824 076 143 2814 WARD 02 ANC 073 008 6374 WARD 24 ANC 083 726 5090 WARD 46 ANC 082 7007 081 WARD 68 DA 078 130 5450 WARD 90 ANC PR-AL JAMA-AH 084 685 2762 Areas: Mgezanyoni, Imbozamo, Mgangeni, Mabedlane, St. -

History Workshop

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND, JOHANNESBURG HISTORY WORKSHOP STRUCTURE AND EXPERIENCE IN THE MAKING OFAPARTHEID 6-10 February 1990 AUTHOR: Iain Edwards and Tim Nuttall TITLE: Seizing the moment : the January 1949 riots, proletarian populism and the structures of African urban life in Durban during the late 1940's 1 INTRODUCTION In January 1949 Durban experienced a weekend of public violence in which 142 people died and at least 1 087 were injured. Mobs of Africans rampaged through areas within the city attacking Indians and looting and destroying Indian-owned property. During the conflict 87 Africans, SO Indians, one white and four 'unidentified' people died. One factory, 58 stores and 247 dwellings were destroyed; two factories, 652 stores and 1 285 dwellings were damaged.1 What caused the violence? Why did it take an apparently racial form? What was the role of the state? There were those who made political mileage from the riots. Others grappled with the tragedy. The government commission of enquiry appointed to examine the causes of the violence concluded that there had been 'race riots'. A contradictory argument was made. The riots arose from primordial antagonism between Africans and Indians. Yet the state could not bear responsibility as the outbreak of the riots was 'unforeseen.' It was believed that a neutral state had intervened to restore control and keep the combatants apart.2 The apartheid state drew ideological ammunition from the riots. The 1950 Group Areas Act, in particular, was justified as necessary to prevent future endemic conflict between 'races'. For municipal officials the riots justified the future destruction of African shantytowns and the rezoning of Indian residential and trading property for use by whites. -

Chapter 9: In-Depth Case Study Analysis

Impact of Township Shopping Centres – July, 2010 CHAPTER NINE: IN-DEPTH CASE STUDY ANALYSIS – UMLAZI MEGA CITY 9.1 INTRODUCTION Umlazi Mega City represents a minor regional centre located in Umlazi, KwaZulu Natal. The purpose of this chapter is multi-fold: Firstly, to provide a profile of the centre under investigation and its location in relation to surrounding supply; Secondly, to provide a socio-economic profile of the primary consumer market of the centre; Thirdly, to provide an overview of past and present consumer market behaviour, overall levels of satisfaction, perceived needs and preferences; Fourthly, to determine the overall impact that the development of the centre had on the local community and economy. 9.2 UMLAZI MEGA CITY PROFILE AND LOCATION WITH REFERENCE TO COMPETITION 9.2.1 UMLAZI MEGA CITY PROFILE Table 9.1 provides a condensed profile of Umlazi Mega City. Overall it is evident that it represents a minor regional centre of 28 000m2 retail GLA, located at 50 Mangosuthu Highway, Umlazi. It was developed in 2006 and consists of a single retail floor with 102 shops and 465 parking bays. It is anchored by Super Spar, Woolworths, Jet and Mr Price. Table 9.1: Umlazi Mega City Profile Centre type Minor regional centre Centre size 28 000m2 retail GLA Location 50 Mangosuthu Highway, Umlazi Date of development 2006 Number of retail floors 1 Number of shops 102 Number of parking bays 465 open Anchor tenants Super Spar Woolworths Jet Mr Price Owner SA Corporate Real Estate Fund Developer Mark II Project Managers Source: Demacon Ex. SACSC, 2010 9.2.2 UMLAZI MEGA CITY LOCATION WITH REFERENCE TO COMPETITION Map 9.1 indicates the location of Umlazi Mega City with reference to existing retail centres within and just beyond a 10km radius. -

National Water

STAATSKOERANT, 7 DESEMBER 2018 No. 42092 69 DEPARTMENT OF WATER AND SANITATION NO. 1366 07 DECEMBER 2018 1366 National Water Act, 1998: Mzimvubu-Tsitsikamma Water Management Area (WMA7) in the Eastern Cape Province: Amending and Limiting the use of Water in terms of Item 6 of Schedule 3 of the Act, for Urban, Agricultural and Industrial (including Mining) purposes 42092 MZIMVUSU- TSIT$IKAMMA WATER MANAGEMENT AREA (WMA 7)IN THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE: AMENDING AND LIMITING THE USE OF WATER IN TERMSOF ITEM 6 OF SCHEDULE 3 OF THE NATIONAL WATER ACT OF 1998;FOR URBAN, AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL (INCLUDING MINING) PURPOSES The Minister of Water and Sanitation has, in terms of item 6(1) of Schedule 3of the National Water Act of 1998 (Act 36 of 1998) (The Act), empowered to limit theuse of water in the area concerned if the Minister, on reasonable grounds, believes that a watershortage exists within the area concerned. This power has been delegated to me in terms of Section63 (1) (b) of the Act. Therefore,I,Deborah Mochotlhi, in my capacity as the Acting Director -Generalof the Department of Water and Sanitation hereby under delegated authority, interms of item 6 (1) of Schedule 3 read with section 72(1) of the Act, publish a notice in the gazetteto amend and limit the taking and storing of water in terms of section 21(a) and 21(b) byall users in the geographical areas listed and described below, as follows: 1. The Algoa Water Supply System (WSS) and associated primary catchments: Decrease the curtailment from 30% to 25% on all taking of waterfrom surface or groundwater resources for domestic and industrial water use from the Algoa WSS and the relevant parts of the catchments within which the Algoa WSSoccurs.