Time to Vote?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide for Scrutineers

GUIDE FOR SCRUTINEERS Form 125 Mar 2021 Role of Scrutineers It is important that candidates are familiar with the duties and responsibilities of the scrutineers that observe proceedings and act on your on your behalf. Scrutineers may observe election activities on your behalf. Up to two scrutineers per candidate may attend at one station at a time (Note: This could be changed to one scrutineer per polling station due to COVID-19 protective measures) Scrutineers will receive identification badges to wear in the polling place. Political affiliation is not permitted on the badges or elsewhere The candidate or the official agent must appoint them in writing on the Appointment of Scrutineer forms, which are available from your Returning Officer. They must have a properly completed appointment and take a declaration of secrecy to be authorized to remain in the polling place. Scrutineers must present the Appointment of Scrutineer form to the election officer and complete a declaration of secrecy at each polling station they attend On the form, you must designate the polling station(s) or registration station(s) they have been appointed to observe. The Elections Act authorizes scrutineers to remain in the polling place while the vote and the ballot count take place. Scrutineers may observe polling day activities. Election officers are authorized to ask scrutineers to leave if they obstruct the taking of the poll, communicate with an elector who has asked not to be spoken to, disrupt the voting process, or commit any offence against the Elections -

Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21St Century

This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting — © 2004 Bev Harris Rights reserved to Talion Publishing/ Black Box Voting ISBN 1-890916-90-0. You can purchase copies of this book at www.Amazon.com. Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21st Century By Bev Harris Talion Publishing / Black Box Voting This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Contents © 2004 by Bev Harris ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Jan. 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever except as provided for by U.S. copyright law. For information on this book and the investigation into the voting machine industry, please go to: www.blackboxvoting.org Black Box Voting 330 SW 43rd St PMB K-547 • Renton, WA • 98055 Fax: 425-228-3965 • [email protected] • Tel. 425-228-7131 This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting © 2004 Bev Harris • ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Dedication First of all, thank you Lord. I dedicate this work to my husband, Sonny, my rock and my mentor, who tolerated being ignored and bored and galled by this thing every day for a year, and without fail, stood fast with affection and support and encouragement. He must be nuts. And to my father, who fought and took a hit in Germany, who lived through Hitler and saw first-hand what can happen when a country gets suckered out of democracy. And to my sweet mother, whose an- cestors hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad, who gets that disapproving look on her face when people don’t do the right thing. -

Randomocracy

Randomocracy A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Why the B.C. Citizens Assembly recommends the single transferable-vote system Jack MacDonald An Ipsos-Reid poll taken in February 2005 revealed that half of British Columbians had never heard of the upcoming referendum on electoral reform to take place on May 17, 2005, in conjunction with the provincial election. Randomocracy Of the half who had heard of it—and the even smaller percentage who said they had a good understanding of the B.C. Citizens Assembly’s recommendation to change to a single transferable-vote system (STV)—more than 66% said they intend to vote yes to STV. Randomocracy describes the process and explains the thinking that led to the Citizens Assembly’s recommendation that the voting system in British Columbia should be changed from first-past-the-post to a single transferable-vote system. Jack MacDonald was one of the 161 members of the B.C. Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform. ISBN 0-9737829-0-0 NON-FICTION $8 CAN FCG Publications www.bcelectoralreform.ca RANDOMOCRACY A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Jack MacDonald FCG Publications Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Copyright © 2005 by Jack MacDonald All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2005 by FCG Publications FCG Publications 2010 Runnymede Ave Victoria, British Columbia Canada V8S 2V6 E-mail: [email protected] Includes bibliographical references. -

How to Run Pandemic-Sustainable Elections: Lessons Learned from Postal Voting

How to run pandemic-sustainable elections: Lessons learned from postal voting Hanna Wass1*, Johanna Peltoniemi1, Marjukka Weide,1,2 Miroslav Nemčok3 1 Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland 2 Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Jyväskylä, Finland 3 Department of Political Science, University of Oslo * Correspondence: [email protected] Keywords: pandemic elections, postponing elections, electoral reform, voter facilitation, convenience voting, postal voting Abstract The COVID-19 pandemic has made it clear that the traditional “booth, ballot, and pen” model of voting, based on a specific location and physical presence, may not be feasible during a health crisis. This situation has highlighted the need to assess whether existing national electoral legislation includes enough instruments to ensure citizens’ safety during voting procedures, even under the conditions of a global pandemic. Such instruments, often grouped under the umbrella of voter facilitation or convenience voting, range from voting in advance and various forms of absentee voting (postal, online, and proxy voting) to assisted voting and voting at home and in hospitals and other healthcare institutions. While most democracies have implemented at least some form of voter facilitation, substantial cross-country differences still exist. In the push to develop pandemic- sustainable elections in different institutional and political contexts, variation in voter facilitation makes it possible to learn from country-specific experiences. As accessibility and inclusiveness are critical components of elections for ensuring political legitimacy and accountability, particularly in times of crisis, these lessons are of utmost importance. In this study, we focus on Finland, where the Parliament decided in March 2021 to postpone for two months the municipal elections that were originally scheduled to be held on April 18. -

Sample Type B Notice for Referendum

FASCIMILE BALLOT NOTICE OF PALMYRA-EAGLE AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT ADVISORY REFERENDUM ELECTION NOVEMBER 5, 2019 OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT CLERK OF THE PALMYRA-EAGLE AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT TO THE ELECTORS OF THE PALMYRA-EAGLE AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT: Notice is hereby given of an advisory referendum election to be held in the Palmyra-Eagle Area School District, on the 5th day of November, 2019 at which the question(s), to be submitted to a vote for an advisory referendum, is shown in the sample ballot below. INFORMATION TO VOTERS Upon entering the polling place, a voter shall state his or her name and address, show an acceptable form of photo identification and sign the poll book before being permitted to vote. If a voter is not registered to vote, a voter may register to vote at the polling place serving his or her residence if the voter provides proof of residence in a form specified by law. Where ballots are distributed to voters, the initials of two inspectors must appear on the ballot. Upon being permitted to vote, the voter shall retire alone to a voting booth or machine and cast his or her ballot except that a voter who is a parent or guardian may be accompanied by the voter's minor child or minor ward. An election official may inform the voter of the proper manner for casting a vote, but the official may not in any manner advise or indicate a particular voting choice. On referenda questions when voting by paper ballot, the elector shall make a cross (X) in the square at the right of “yes” if in favor of the question, or the elector shall make a cross (X) in the square at the right of “no” if opposed to the question. -

Convenience Voting

ANRV344-PL11-19 ARI 28 January 2008 15:20 V I E E W R S I E N C N A D V A Convenience Voting Paul Gronke, Eva Galanes-Rosenbaum, Peter A. Miller, and Daniel Toffey Department of Political Science and The Early Voting Information Center, Reed College, Portland, Oregon 97202; email: [email protected]; [email protected] Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2008. 11:437–55 Key Terms The Annual Review of Political Science is online at early voting, absentee voting, turnout, election administration, http://polisci.annualreviews.org elections, vote by mail This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053006.190912 Abstract Copyright c 2008 by Annual Reviews. ! Forms of convenience voting—early in-person voting, voting by All rights reserved mail, absentee voting, electronic voting, and voting by fax—have be- 1094-2939/08/0615-0437$20.00 come the mode of choice for >30% of Americans in recent elections. Despite this, and although nearly every state in the United States has adopted at least one form of convenience voting, the academic re- search on these practices is unequally distributed across important questions. A great deal of literature on turnout is counterbalanced by a dearth of research on campaign effects, election costs, ballot quality, and the risk of fraud. This article introduces the theory of convenience voting, reviews the current literature, and suggests areas for future research. 437 ANRV344-PL11-19 ARI 28 January 2008 15:20 INTRODUCTION voting.2 Every convenience voting method Convenience voting is typically understood aims to give potential voters easier access to to mean any mode of balloting other than the ballot, even if, in some cases, it might mean precinct-place voting. -

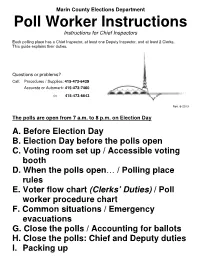

Poll Worker Instructions Instructions for Chief Inspectors

Marin County Elections Department Poll Worker Instructions Instructions for Chief Inspectors Each polling place has a Chief Inspector, at least one Deputy Inspector, and at least 2 Clerks. This guide explains their duties. Questions or problems? Call: Procedures / Supplies: 415-473-6439 Accuvote or Automark: 415-473-7460 Or 415-473-6643 Rev. 6-2013 The polls are open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. on Election Day A. Before Election Day B. Election Day before the polls open C. Voting room set up / Accessible voting booth D. When the polls open … / Polling place rules E. Voter flow chart (Clerks’ Duties) / Poll worker procedure chart F. Common situations / Emergency evacuations G. Close the polls / Accounting for ballots H. Close the polls: Chief and Deputy duties I. Packing up A. Before Election Day – Chief Inspector Duties ♣ Pick up a red bag at the training class. Do not open the sealed This bag contains: a black Accuvote bag, a polling place portion of the Accuvote accessibility supply bag, a Vote by Mail Ballot Box, and other bag until Election Day. supplies you will need. ♣ Use the inventory list in the red bag to make sure your red bag has all the supplies you need. ♣ Call your polling place contact (listed on your supply receipt) to make sure you can get into the polling place on Election Day by 6:30 a.m., or earlier. Important! Take this person’s contact info with you on Election Day in case you have any problems getting in. ♣ Call your Deputy Inspector(s) to tell them what time to meet you at the polling place on Election Day. -

If You Don't Know How to Get Started, Just Ask a Question

Module 8 Get Public Records and Freedom of Information Documents Public records are the kind of evidence that can stand up in a court of law. And like a box o' chocolates, you never know what you're gonna get. Guide for Requesting Public Documents Goals: Get provable documentation to find out what's really going on. Anything that's on paper or e-mail at a government agency is fair game, with a small handful of exceptions. You can't use public records request to ask a question, but you can use them to ask for documents. All you have to do is try to imagine what documents might contain answers to your questions, and request those records. It is the legal obligation of governmental agencies to provide the documents you request. How to Ask For Public Documents • Label your request "Public Records Request" if you are requesting it from a state or local governmental entity, or "Freedom of Information Act Request" if you are requesting it from a federal governmental entity. • Make sure to date it and provide an address for them to send responses. • You cannot request a record before it exists. To request election audit logs, for example, you need to wait until the election events have taken place. C ITIZEN' S T OOL K IT TO T AKE B ACK Y OUR E LECTIONS http://www.blackboxvoting.org/toolkit.pdf © Black Box Voting Inc. 2006 8/14/06 edition • Once you have requested a record, it is illegal to destroy it. If you think you might need a time-sensitive record but you aren't sure, request it as soon as possible and ask that they quote you a price for it. -

Guidelines for News Media During Elections

VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF ELECTIONS GUIDELINES FOR NEWS MEDIA DURING ELECTIONS These guidelines provide an overview of the restrictions applicable to media outlets and their activities inside polling locations on Election Day. News media representatives may visit, film and photograph inside Virginia polling places on Election Day for a reasonable and limited period of time while the polls are open. Media representatives may not disrupt the smooth operation of the election; voters and officers of election must not feel uncomfortable with their presence or have their privacy violated. Before Election Day: While the Department highly recommends that all media outlets contact the general registrar of the relevant locality prior to visiting any polling locations on Election Day, Va. Code § 24.2-604 states “the officers of election shall permit representatives of the news media to visit and film and photograph inside the polling location for a reasonable and limited period of time while the polls are open.” Certain restrictions apply, e.g., such as the media is prohibited from hindering or delaying a voter in any way. Further, if a majority of the officers of election conclude that the media outlet is not complying with state law, then the officers of election are authorized to require any news outlet to leave the polling location. Again, the Department recommends that any media outlet planning or considering filming on Election Day contact the general registrar well in advance of the election. You can find contact information for individual registrar offices on the Department of Elections’ (ELECT) website (elections.virginia.gov). Pursuant to Va. -

7Closing the Polls

ELECTION JUDGE/COORDINATOR HANDBOOK | GENERAL ELECTION 2020 CHAPTER 6 CLOSING THE POLLS Election Day 7:00 pm 7 Chapter 7 gives step-by-step instructions on closing the polls, reporting the voting, and completing end of night procedures. CLOSING THE POLLING PLACE – STEP BY STEP First, read the quick overview of all the procedures to close the polls. Then, see the detailed instructions that follow for each of the steps, #1-16. Quick Overview: Closing the Polls ❏ 1. Close the polls. ❏ 2. Find the Certificate of Results (Form 80) and a set of envelopes. You will fill it in as you work through all closing procedures. ❏ 3. Process any defective or damaged ballots. ❏ 4. Count and record the provisional ballots, spoiled provisional ballots, and spoiled affidavits. ❏ 5. Close the e-poll books. ❏ 6. Close the polls on the touchscreen. ❏ 7. Close polls on the ballot scanner and print all copies of the Official Results Tape ❏ 8. Transmit the results and remove the memory cards from the ballot scanner. ❏ 9. Process voted ballots with valid write-in votes. ❏ 10. Separately count and record all spoiled, damaged, and unused ballots. ❏ 11. Complete, hand-copy, and sign the Certificate of Results (Form 80). ❏ 12. Put ballots, reports, and related items into the Transfer Case, to go back to the Receiving Station. ❏ 13. Put required equipment, envelopes, and other items in the Black Return Bag to go back to the Receiving Station. ❏ 14. Lock specified equipment and supplies back into the ESC. ❏ 15. Leave the polling place neat and clean. ❏ 16. Return all required equipment and materials to the Receiving Station; leave the rest locked in the polling place. -

Case 2:20-Cv-00966-NR Document 409 Filed 08/23/20 Page 1 of 37

Case 2:20-cv-00966-NR Document 409 Filed 08/23/20 Page 1 of 37 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA No. 2:20-cv-966 DONALD J. TRUMP FOR PRESIDENT, INC., et al., Plaintiffs v. KATHY BOOCKVAR, in her capacity as Secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, et al., Defendants. OPINION J. Nicholas Ranjan, United States District Judge Plaintiffs in this case are President Trump’s reelection campaign, the Republican National Committee, and several other Republican congressional candidates and electors. They filed this suit, alleging federal and state constitutional violations stemming from Pennsylvania’s recent implementation of a mail-in voting plan. In their complaint, Plaintiffs point to the 2020 primary election, where “no excuse” mail-in voting was first implemented in Pennsylvania, and describe an election plagued by chaos. They say the primary was a “hazardous, hurried, and illegal implementation of unmonitored mail-in voting which provides fraudsters an easy opportunity to engage in ballot harvesting, - 1 - Case 2:20-cv-00966-NR Document 409 Filed 08/23/20 Page 2 of 37 manipulate or destroy ballots, manufacture duplicitous votes, and sow chaos.” [ECF 234, ¶ 1]. They fear the same will occur in the November general election, where much more, of course, is at stake. According to Plaintiffs, Pennsylvania’s mail-in voting plan is not just bad, but unconstitutional. They say it is a product of overreach by the Pennsylvania Secretary of the Commonwealth, Kathy Boockvar, that will lead to “vote dilution” (i.e., if unlawful votes are counted, then that “dilutes” lawful votes). -

Unfolding the Concept of Convenience Voting: Definition, Types, Benefits and Barriers

TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY School of Business and Governance Department of Ragnar Nurkse Grace Muthoni Muchiri Unfolding the Concept of Convenience Voting: Definition, Types, Benefits and Barriers. Master’s thesis HAGM; Technology Governance and Digital Transformation Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Dr. Robert Krimmer Co-supervisors: Dr. David Duenas- Cid, PhD Iuliia Krivonosova Tallinn 2021 I hereby declare that I have compiled the thesis independently and all works, important standpoints and data by other authors have been properly referenced and the same paper has not been previously presented for grading. The document length is 13567 words from the introduction to the end of conclusion. Grace Muthoni Muchiri ……………………………10.05.2021 Student code: 194561HAGM Student e-mail address: [email protected] Supervisor: Prof. Dr Dr Robert Krimmer The paper conforms to requirements in force …………………………………………… (signature, date) Co-supervisor: Dr. David Duenas- Cid, PhD The paper conforms to requirements in force …………………………………………… (signature, date) Co-supervisor: Iuliia Krivonosova The paper conforms to requirements in force …………………………………………… (signature, date) Chairman of the Defence Committee: Permitted to the defence. ………………………………… (name, signature, date) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am indebted to my supportive parents, George Muchiri and Loise Njeri for their support and encouragement through this process. A special thanks of gratitude to my supervisors: Prof Dr Dr Robert Krimmer, Dr David Dueñas Cid and Iuliia Krivonosova who have continuously and graciously offered me guidance and support in writing this thesis. Your thorough guidance and friendly approach in instilling the skills of a researcher in me have gone a long way in building my academic profile. You all are very exceptional.