Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

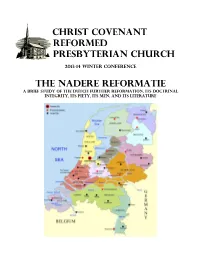

Nadere Reformatie Lecture 1

CHRIST COVENANT Reformed PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH 2013-14 WINTER CONFERENCE THE NADERE REFORMATIE A Brief Study of the Dutch Further Reformation, its doctrinal integrity, its piety, its men, and its Literature Nadere Reformatie Lectures-Pastor Ruddell’s Notes 1) The Name: Nadere Reformatie a) The name itself is a difficult term. It has been translated as: i) Second Reformation: As a name, the second reformation has something to be said for it, but it may give the impression that it is something separate from the first reformation, it denies the continuity that would have been confessed by its adherents. ii) Further Reformation: This is the term that is popular with Dutch historians who specialize in this movement. This term is preferred because it does set forth a continuity with the past, and with the Protestant Reformation as it came to the Netherlands. Its weakness is that it may seem to imply that the original Reformation did not go far enough—that there ought to be some noted deficiency. iii) The movement under study has also been called “Dutch Precisianism” as in, a more precise and exacting practice of godliness or piety. The difficulty here is that there are times when that term “precisionist” has been used pejoratively, and historians are unwilling to place a pejorative name upon a movement so popular with godly Dutch Christians. iv) There are times when the movement has been referred to as “Dutch Puritanism”. And, while there is much to commend this name as well, Puritanism also carries with it a particular stigma, which might be perceived as unpopular. -

Literaturverzeichnis in Auswahl1

Literaturverzeichnis in Auswahl1 A ADAMS, THOMAS: An Exposition upon the Second Epistle General of St. Peter. Herausgegeben von James Sherman. 1839. Nachdruck Ligonier, Pennsylvania: Soli Deo Gloria, 1990. DERS.: The Works of Thomas Adams. Edinburgh: James Nichol, 1862. DERS.: The Works of Thomas Adams. 1862. Nachdruck Eureka, California: Tanski, 1998. AFFLECK, BERT JR.: „The Theology of Richard Sibbes, 1577–1635“. Doctor of Philosophy-Dissertation: Drew University, 1969. AHENAKAA, ANJOV: „Justification and the Christian Life in John Bunyan: A Vindication of Bunyan from the Charge of Antinomianism“. Doctor of Philosophy-Dissertation: Westminster Theological Seminary, 1997. AINSWORTH, HENRY: A Censure upon a Dialogue of the Anabaptists, Intituled, A Description of What God Hath Predestinated Concerning Man. & c. in 7 Poynts. Of Predestination. pag. 1. Of Election. pag. 18. Of Reprobation. pag. 26. Of Falling Away. pag. 27. Of Freewill. pag. 41. Of Originall Sinne. pag. 43. Of Baptizing Infants. pag. 69. London: W. Jones, 1643. DERS.: Two Treatises by Henry Ainsworth. The First, Of the Communion of Saints. The Second, Entitled, An Arrow against Idolatry, Etc. Edinburgh: D. Paterson, 1789. ALEXANDER, James W.: Thoughts on Family Worship. 1847. Nachdruck Morgan, Pennsylvania: Soli Deo Gloria, 1998. ALLEINE, JOSEPH: An Alarm to the Unconverted. Evansville, Indiana: Sovereign Grace Publishers, 1959. DERS.: A Sure Guide to Heaven. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1995. ALLEINE, RICHARD: Heaven Opened … The Riches of God’s Covenant of Grace. New York: American Tract Society, ohne Jahr. ALLEN, WILLIAM: Some Baptismal Abuses Briefly Discovered. London: J. M., 1653. ALSTED, JOHANN HEINRICH: Diatribe de Mille Annis Apocalypticis ... Frankfurt: Sumptibus C. Eifridi, 1627. -

A Memorial Volume of St. Andrews University In

DUPLICATE FROM THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND. GIFT OF VOTIVA TABELLA H H H The Coats of Arms belong respectively to Alexander Stewart, natural son James Kennedy, Bishop of St of James IV, Archbishop of St Andrews 1440-1465, founder Andrews 1509-1513, and John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews of St Salvator's College 1482-1522, cofounders of 1450 St Leonard's College 1512 The University- James Beaton, Archbishop of St Sir George Washington Andrews 1 522-1 539, who com- Baxter, menced the foundation of St grand-nephew and representative Mary's College 1537; Cardinal of Miss Mary Ann Baxter of David Beaton, Archbishop 1539- Balgavies, who founded 1546, who continued his brother's work, and John Hamilton, Arch- University College bishop 1 546-1 57 1, who com- Dundee in pleted the foundation 1880 1553 VOTIVA TABELLA A MEMORIAL VOLUME OF ST ANDREWS UNIVERSITY IN CONNECTION WITH ITS QUINCENTENARY FESTIVAL MDCCCCXI MCCCCXI iLVal Quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis Horace PRINTED FOR THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND COMPANY LIMITED MCMXI GIF [ Presented by the University PREFACE This volume is intended primarily as a book of information about St Andrews University, to be placed in the hands of the distinguished guests who are coming from many lands to take part in our Quincentenary festival. It is accordingly in the main historical. In Part I the story is told of the beginning of the University and of its Colleges. Here it will be seen that the University was the work in the first instance of Churchmen unselfishly devoted to the improvement of their country, and manifesting by their acts that deep interest in education which long, before John Knox was born, lay in the heart of Scotland. -

Hidden Lives: Asceticism and Interiority in the Late Reformation, 1650-1745

Hidden Lives: Asceticism and Interiority in the Late Reformation, 1650-1745 By Timothy Cotton Wright A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonathan Sheehan, chair Professor Ethan Shagan Professor Niklaus Largier Summer 2018 Abstract Hidden Lives: Asceticism and Interiority in the Late Reformation, 1650-1745 By Timothy Cotton Wright Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonathan Sheehan, Chair This dissertation explores a unique religious awakening among early modern Protestants whose primary feature was a revival of ascetic, monastic practices a century after the early Reformers condemned such practices. By the early seventeenth-century, a widespread dissatisfaction can be discerned among many awakened Protestants at the suppression of the monastic life and a new interest in reintroducing ascetic practices like celibacy, poverty, and solitary withdrawal to Protestant devotion. The introduction and chapter one explain how the absence of monasticism as an institutionally sanctioned means to express intensified holiness posed a problem to many Protestants. Large numbers of dissenters fled the mainstream Protestant religions—along with what they viewed as an increasingly materialistic, urbanized world—to seek new ways to experience God through lives of seclusion and ascetic self-deprival. In the following chapters, I show how this ascetic impulse drove the formation of new religious communities, transatlantic migration, and gave birth to new attitudes and practices toward sexuality and gender among Protestants. The study consists of four case studies, each examining a different non-conformist community that experimented with ascetic ritual and monasticism. -

Scottísh Ecclesiastical Anti G Eneral Calendar

Scottísh Ecclesiastical anti G eneral Calendar. MAY 1928. 1 T. ZS, Philip and James. David Livingstone d. 1873. 2 W. S. Athanasius (373). Prin. J. Marshall Lang d. 1909. 3 Th. Archbishop Sharp murdered 1679. Thomas Hood d. 1845. 4 F. Sir T. Lawrence b. 1769. T. Huxley b. 1818. 5 S. Napoleon I. cl. 1821. Karl Marx b. 1818. 6 after Easter. Accession King George V. Jansen d. 1638. 7 M. Earl Rosebery b. 1847. A. Harnack b. 1851. 8 T. Dante b. 1265. John Stuart Mill cl. 1873. g W. Sir J. M. Barrie b. 1860. Vindictive sunk Ostend 1918. io Th. Indian Mutiny, Meerut, 1857. Bp. James Kennedy d. 1466. II F. Margaret Wilson and Margaret M`Lachlan, Wigtown, martyred 1685. 12 S. S. Congall, Durris (602). D. G. Rossetti b. 1828. 13 D Battle of Langside 1568. U.P. Church formed 1847. 14 M. E. Fitzgerald cl. 1883. Vimy Ridge 1916. 15 T. Whitsunday TeIm. Queen Mary and Bothwell ni. 1567. 16 W. S. Brendan, Voyager (577). Court of Session Instd. 1532. 17 Th. Ascension Bap. S. Cathan, Bute (710). R.V. New Test. published 1881. 18 F. The " Disruption," 1843. G. Meredith d. 1909. 19 S. Prof. Wilson (Chris. North) b. 1785. Gladstone d. 1898. 20 Thos. Boston cl. 1732. William Chambers cl. 1883. 21 M. Montrose exted. 1649. Miss Walker-Arnott, Jaffa, cl. 1911. 22 T. 7th Royal Scots disaster, Gretna, 1915. R. Wagner b. 1813. 23 W. St Giles' Cathedral reopened 1883. Savonarola burnt 1498. 24 Th. Queen Victoria b. 1819. John G. -

14 Councils, Counsel and the Seventeenth-Century Composite

1 14 Councils, Counsel and the Seventeenth-Century Composite State* JACQUELINE ROSE In the closing pages of his treatise ‘Of the union of Britayne’, the Presbyterian clergyman Robert Pont sought to reassure his fellow Scots and English neighbours that a union of their kingdoms merely enlarged and would not change their commonwealth. ‘If any small differences arise’, Pont blithely declared, ‘they wil be by sage counsel easily reconcyled’.1 In the honeymoon days of 1604, when James VI’s accession to the throne of England seemed to promise the fulfilment of God’s plan for a Protestant British imperium, Pont’s optimism was excusable. His reticence in spelling out the details of joint or coordinate British conciliar mechanisms was, in part, a typical humanist adherence to the moral economy of counsel which floated loftily above institutional specificities. Pont’s interlocutors express admiration for a princely commonwealth which is tempered by aristocracy. Both England and Scotland avoided the risk of tyranny by founding their commonwealths ‘upon such a ground, where one kinge by the counsell of his nobility ruled all’.2 This was less English ancient constitutionalism than Scottish aristocratic conciliarism. But Pont’s silence on the details of British councils was typical of many writers in the Jacobean union debates and beyond. * My thanks to all those who commented on drafts of this article. 1 The Jacobean Union: Six Tracts of 1604, ed. B. R. Galloway and B. P. Levack (Edinburgh, Scottish History Society, 4th ser., 21, 1985), p. 24. 2 Jacobean Union: Six Tracts, pp. 1-2. 2 That the seventeenth-century Atlantic archipelago was plagued by the problem of being a composite state is well known. -

Title Page R.J. Pederson

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/22159 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Pederson, Randall James Title: Unity in diversity : English puritans and the puritan reformation, 1603-1689 Issue Date: 2013-11-07 UNITY IN DIVERSITY: ENGLISH PURITANS AND THE PURITAN REFORMATION 1603-1689 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. Carel Stolker volgens besluit van het College voor promoties te verdedigen op 7 November 2013 klokke 15:00 uur door Randall James Pederson geboren te Everett, Washington, USA in 1975 Promotiecommissie Promotores: Prof. dr. Gijsbert van den Brink Prof. dr. Richard Alfred Muller, Calvin Theological Seminary, Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA Leden: Prof. dr. Ernestine van der Wall Dr. Jan Wim Buisman Prof. dr. Henk van den Belt Prof. dr. Willem op’t Hof Dr. Willem van Vlastuin Contents Part I: Historical Method and Background Chapter One: Historiographical Introduction, Methodology, Hypothesis, and Structure ............. 1 1.1 Another Book on English Puritanism? Historiographical Justification .................. 1 1.2 Methodology, Hypothesis, and Structure ...................................................................... 20 1.2.1 Narrative and Metanarrative .............................................................................. 25 1.2.2 Structure ................................................................................................................... 31 1.3 Summary ................................................................................................................................ -

TMSJ 5/1 (Spring 1994) 43-71

TMSJ 5/1 (Spring 1994) 43-71 DOES ASSURANCE BELONG TO THE ESSENCE OF FAITH? CALVIN AND THE CALVINISTS Joel R. Beeke1 The contemporary church stands in great need of refocusing on the doctrine of assurance if the desirable fruit of Christian living is to abound. A relevant issue in church history centers in whether or not the Calvinists differed from Calvin himself regarding the relationship between faith and assurance. The difference between the two was quantitative and method- ological, not qualitative or substantial. Calvin himself distinguished between the definition of faith and the reality of faith in the believer's experience. Alexander Comrie, a representative of the Dutch Second Reformation, held essentially the same position as Calvin in mediating between the view that assurance is the fruit of faith and the view that assurance is inseparable from faith. He and some other Calvinists differ from Calvin in holding to a two-tier approach to the consciousness of assurance. So Calvin and the Calvinists furnish the church with a model to follow that is greatly needed today. * * * * * Today many infer that the doctrine of personal assurance`that is, the certainty of one's own salvation`is no longer relevant since nearly all Christians possess assurance in an ample degree. On the contrary, it is probably true that the doctrine of assurance has particular relevance, because today's Christians live in a day of minimal, not maximal, assurance. Scripture, the Reformers, and post-Reformation men repeatedly 1Joel R. Beeke, PhD, is the Pastor of the First Netherlands Reformed Congregation, Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Theological Instructor for the Netherlands Reformed Theological School. -

Post-Reformation Reformed Sources and Children1

Post-Reformation Reformed sources 1 and children A C Neele Jonathan Edwards Center Yale University (USA) Abstract This article suggests that the topic “children” received considerable attention in the post-Reformation era – the period of CA 1565-1725. In particular, the author argues that the post-Reformation Reformed sources attest of a significant interest in the education and parenting of children. This interest not only continued, but intensified during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation when much thought was given to the subject matter. This article attempts to appraise the aim of post-Reformation Reformed sources on the topic “children.” 1. INTRODUCTION The theology of the post-Reformation era, which includes Puritanism, German Pietism and the Nadere Reformatie – a Dutch intra-ecclesiastical movement – has been appraised as a period of theological divergence from the sixteenth- century Protestant Reformation (Corley, Lemke & Lovejoy 2002:119).2 More precise, its theology has been characterized as dogmatic mostly rigid and polemic; that is an abstract doctrine with little or no regard for practical significance. Furthermore, the post-Reformation concern for doctrine has been regarded as leading to the relapse to Scholasticism and the neglect of the vitality of the Reformers’ humanism, such as John Calvin (1509-1564) (Ritschl 1880:86; Van der Linde 1976:47; Van’t Spijker 1993:13-14 & Graafland 1961:66). In addition, these and other scholars note an aberration in the theology of the Nadere Reformatie from the sixteenth-century 1 This article is based on a paper presented at the annual meeting of Church Historians of Southern Africa, University of Stellenbosch, 16-18 January, 2006. -

Scholasticism and the Problem of Intellectual Reform

Tilburg University Introduction Wisse, P.M.; Sarot, M. Published in: Scholasticism reformed Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Wisse, P. M., & Sarot, M. (2010). Introduction: Reforming views of reformed scholasticism. In P. M. Wisse, M. Sarot, & W. Otten (Eds.), Scholasticism reformed: Essays in honour of Willem J. van Asselt (Published on the occasion of the retirement of Willem J. van Asselt from Utrecht University) (pp. 1-27). (Studies in theology and religion; No. 14). Brill. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. sep. 2021 Reforming Views of Reformed Scholasticism Introduction Maarten Wisse and Marcel Sarot 1 Introduction The title of the present work is intentionally ambiguous: Scholasticism Reformed. It may be read, firstly, as a simple reversion of “Reformed scholasticism,” as indeed some of the contributions to this volume study aspects of the type of theology between the early Reformation and the Enlightenment that continued to use the traditional methods rooted in the medieval period. -

The Presbyterian Interpretation of Scottish History 1800-1914.Pdf

Graeme Neil Forsyth THE PRESBYTERIAN INTERPRETATION OF SCOTTISH HISTORY, 1800- 1914 Ph. D thesis University of Stirling 2003 ABSTRACT The nineteenth century saw the revival and widespread propagation in Scotland of a view of Scottish history that put Presbyterianism at the heart of the nation's identity, and told the story of Scotland's history largely in terms of the church's struggle for religious and constitutional liberty. Key to. this development was the Anti-Burgher minister Thomas M'Crie, who, spurred by attacks on Presbyterianism found in eighteenth-century and contemporary historical literature, between the years 1811 and 1819 wrote biographies of John Knox and Andrew Melville and a vindication of the Covenanters. M'Crie generally followed the very hard line found in the Whig- Presbyterian polemical literature that emerged from the struggles of the sixteenth and seventeenth century; he was particularly emphatic in support of the independence of the church from the state within its own sphere. His defence of his subjects embodied a Scottish Whig interpretation of British history, in which British constitutional liberties were prefigured in Scotland and in a considerable part won for the British people by the struggles of Presbyterian Scots during the seventeenth century. M'Crie's work won a huge following among the Scottish reading public, and spawned a revival in Presbyterian historiography which lasted through the century. His influence was considerably enhanced through the affinity felt for his work by the Anti- Intrusionists in the Church of Scotland and their successorsin the Free Church (1843- 1900), who were particularly attracted by his uncompromising defence of the spiritual independence of the church.