Migration, Food and Cultural Production Across Changing Afro- Ecuadorian Geographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Profile Copia

ECUADOR One of the most biodiverse countries in the world Index General facts Geography Society Food Economy Government Fundación VASE Volunteer service General Facts Capital City: Quito Currency: US Dollar Official Languages: Spanish and Kichwa Government: Unitary Presidential Constitutional Republic President: Lenin Moreno Geography Straddling the equator in western South America, Ecuador has land in both the Northern and the Southern hemisphere It borders Colombia in the North and Peru in the South and the East. The Pacific Ocean is Ecuador’s western border. The land area totals 283.560km², including the Galapagos Islands. The border with Colombia is 590km and the border with Peru 1.420km long. Ecuador’s coast line has a length of 2.237km. The “Mitad del Mundo –Center of the world” is where the equator crosses Ecuador at latitude 0°0°0. Geographic Regions Galapagos Islands - Costa (Coast) - Sierra (Andes) – Amazonia (Rainforest) Galápagos The islands are known for their large number of endemic species and were studied by Charles Darwin during the second voyage of HMS Beagle. His observations and collections contributed to the inception of Darwin's theory of evolution by means of natural selection. The Galápagos Islands and their surrounding waters form the Galápagos Province of Ecuador, the Galápagos National Park, a nd the Galápagos Marine Reserve. The Coast (tropical weather, 23-26°C ) This region consists of the low-lying Western part of the country, including all of the Pacific coastline. The coastal plain extends far inland, as far as the foothills of the Andes mountain range. The region originally was forest, but most of the woodland have been cleared for timber, cattle ranging and agriculture. -

“Urbanization in Ecuador: an Overview Using the FUA Definition”

Institut de Recerca en Economia Aplicada Regional i Pública Document de Treball 2018/14, 18 pàg. Research Institute of Applied Economics Working Paper 2018/14, 18 pag. Grup de Recerca Anàlisi Quantitativa Regional Document de Treball 2018/07, 18 pàg. Regional Quantitative Analysis Research Group Working Paper 2018/07, 18 pag. “Urbanization in Ecuador: An overview using the FUA definition” Obaco M & Díaz-Sánchez J P WEBSITE: www.ub-irea.com • CONTACT: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.ub.edu/aqr/ • CONTACT: [email protected] Universitat de Barcelona Av. Diagonal, 690 • 08034 Barcelona The Research Institute of Applied Economics (IREA) in Barcelona was founded in 2005, as a research institute in applied economics. Three consolidated research groups make up the institute: AQR, RISK and GiM, and a large number of members are involved in the Institute. IREA focuses on four priority lines of investigation: (i) the quantitative study of regional and urban economic activity and analysis of regional and local economic policies, (ii) study of public economic activity in markets, particularly in the fields of empirical evaluation of privatization, the regulation and competition in the markets of public services using state of industrial economy, (iii) risk analysis in finance and insurance, and (iv) the development of micro and macro econometrics applied for the analysis of economic activity, particularly for quantitative evaluation of public policies. IREA Working Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. For that reason, IREA Working Papers may not be reproduced or distributed without the written consent of the author. -

The Contribution of the Afro-Descendant Soldiers to the Independence of the Bolivarian Countries (1810-1826)

Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad ISSN: 1909-3063 [email protected] Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Colombia Reales, Leonardo The contribution of the afro-descendant soldiers to the independence of the bolivarian countries (1810- 1826) Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad, vol. 2, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2007 Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=92720203 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REVISTA - Bogotá (Colombia) Vol. 2 No. 2 - Julio - Diciembre 11 rev.relac.int.estrateg.segur.2(2):11-31,2007 THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE AFRO-DESCENDANT SOLDIERS TO THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE BOLIVARIAN COUNTRIES (1810-1826) Leonardo Reales (Ph.D. Candidate - The New School University) ABSTRACT In the midst of the independence process of the Bolivarian nations, thousands of Afro-descendant soldiers were incorporated into the patriot armies, as the Spanish Crown had done once independence was declared. What made people of African descent support the republican cause? Was their contribution to the independence decisive? Did Afro-descendant women play a key role during that process? Why were the most important Afro-descendant military leaders executed by the Creole forces? What was the fate of those soldiers and their descendants at the end of the war? This paper intends to answer these controversial questions, while explaining the main characteristics of Recibido: 3 de septiembre 2007 Aceptado: 8 de octubre 2007 society throughout the five countries freed by the Bolivarian armies in the 1810s and 1820s. -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

Living and Learning in Quito, Ecuador

Living and Learning in Quito, Ecuador A Semester Abroad Experience Living and Learning in Quito, Ecuador Semester Abroad Study Program Living and Learning in Quito, Ecuador is a study abroad program available to students who desire to continue their college education in an international setting. Living and Learning in Quito will function under the supervision and guidelines of your North American institution. This 13-week semester is designed to combine classroom learning and practical internships in a unique and challenging cross-cultural setting. Along with receiving up to 16 units of college credit, students will live, learn and grow academically, experientially, and spiritually. The men and women who participate in this program will be asked to consider how they can use their gifts and talents to reach the world with the good news of Jesus Christ. While living in Quito for 13 weeks students will experience a variety of new cultures, gain a global perspective and understand in a new way the joys and the challenges of serving God in a cross-cultural setting. Students will enjoy the rich interaction with teachers, faculty, and ministry site hosts in a classroom setting, as well as on a one-to-one level. We believe this unique opportunity and setting will lend itself to life long impact. If you accept this challenge, you will: • LEARN through Spanish language study and interdisciplinary seminars about Latin culture, history, ecology, politics, economics, and religion. • LEARN through college level courses that apply toward your major • LIVE with Ecuadorian families, improving your Spanish and sharing your life with Latin American Christians. -

A Key Ingredient for Successful Peacekeeping Operations Management by Joseph L

No. 04-6W Landpower Essay October 2004 An Institute of Land Warfare Publication Special Operators: A Key Ingredient for Successful Peacekeeping Operations Management by Joseph L. Homza Low-intensity operations cannot be won or contained by military power alone. They require the application of all elements of national power across the entire range of conditions which are the source of the conflict.1 U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, Special Forces Peacekeeping is not a job for soldiers, but only a soldier can do it.2 Former United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammerskold Multinational and regional alliances, as well as the Charter of the United Nations, include “terms that reflect a determination to provide an international institution that could control conflict” in the Low-Intensity Conflict (LIC) spectrum of war.3 As a defense contractor employed by Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation, I recently had a unique opportunity to participate directly in the Military Observer Mission Ecuador and Peru (MOMEP), an LIC reduction operation conducted by conventional military forces with management influence by Special Operations Forces (SOF). The tenets of campaign analysis—e.g., military historical perspectives, force structure, command and control capabilities and military objectives—provide a paradigm to demonstrate clearly the effectiveness of this conflict management mission performed by SOF in accordance with the ten focus areas stipulated by John M. Collins in Special Operations Forces: An Assessment.4 The MOMEP Confidence Building Measure (CBM) was an example of SOF and conventional military force elements at their operational best. The Organization of American States (OAS), due to the actions of the SOF and conventional units assigned to MOMEP, would experience a successful CBM Peacekeeping Operation (PKO) in a regional context. -

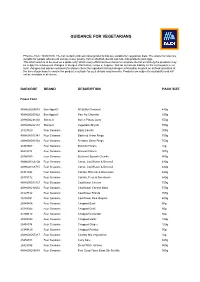

Guidance for Vegetarians

GUIDANCE FOR VEGETARIANS Effective from: 16/05/2020. The list contains Aldi own label products that are suitable for vegetarian diets. The products listed are suitable for people who do not eat any meat, poultry, fish or shellfish, but do eat milk, milk products and eggs. This information is to be used as a guide only; whilst every effort has been taken to complete the list accurately the products may be subject to subsequent changes in allergen information, recipe or supplier. Aldi do not accept liability for the consequences of such changes and advise customers to always check the ingredient list and allergen information on pack on all food and drink at the time of purchase to ensure the product is suitable for your dietary requirements. Products are subject to availability and will not be available in all stores. BARCODE BRAND DESCRIPTION PACK SIZE Frozen Food 4088600205915 Bon Appetit! All Butter Croissant 440g 4088600205922 Bon Appetit! Pain Au Chocolat 390g 4088600233130 Slimwell Sweet Potato Curry 550g 4088600242101 Slimwell Vegetable Biryani 550g 25127829 Four Seasons Baby Carrots 907g 4088600033341 Four Seasons Battered Onion Rings 750g 4088600033334 Four Seasons Breaded Onion Rings 750g 25288667 Four Seasons Broccoli Florets 1kg 25242744 Four Seasons Broccoli Florets 907g 25468359 Four Seasons Butternut Squash Chunks 500g 4088600168708 Four Seasons Carrot, Cauliflower & Broccoli 640g 4088600168715 Four Seasons Carrot, Cauliflower & Broccoli 640g 25314892 Four Seasons Carrots, Broccoli & Sweetcorn 640g 25315172 Four Seasons Carrots, -

Guidance for People Avoiding Milk & Lactose

GUIDANCE FOR PEOPLE AVOIDING MILK & LACTOSE Effective from: 16/05/2020. The list contains Aldi own label products that are suitable for people avoiding milk and lactose. The products listed do not contain milk or ingredients derived from milk and controls are in place to minimise the risk of cross contamination with milk and milk derivatives. This information is to be used as a guide only; whilst every effort has been taken to complete the list accurately the products may be subject to subsequent changes in allergen information, recipe or supplier. Aldi do not accept liability for the consequences of such changes and advise customers to always check the ingredient list and allergen information on pack on all food and drink at the time of purchase to ensure the product is suitable for your dietary requirements. Products are subject to availability and will not be available in all stores. BARCODE BRAND DESCRIPTION PACK SIZE Frozen Food 4088600113326 Slimwell Chicken & Chorizo-Style Sausage Paella 550g 4088600107028 Inspired Cuisine Chicken And Vegetable Fajita Mix 700g 4088600075914 Slimwell Chicken Chow Mein 550g 4088600231495 Everyday Essentials Chicken Curry 400g 4088600209630 Slimwell Meatballs & Pasta 550g 4088600284811 Inspired Cuisine Roast Chicken Dinner 400g 4088600021577 Slimwell Smokey Barbecue Chicken 500g 4088600069937 Inspired Cuisine Sweet And Sour Chicken With Rice 400g 4088600265865 The Fishmonger Basa Fillets 380g 4088600186337 The Fishmonger Battered Chunky Cod 500g 4088600186351 The Fishmonger Battered Chunky Haddock -

1 Border War Between Ecuador and Peru

1 Student: Solveig Karin Erdal pn: 810711 7684 Border War between Ecuador and Peru -Can there be Positive Peace without the Indians? Peace and Conflict Studies C level, 41-60 points Autumn 2003 Malmö University Supervisor: Peter Hervik 2 Table of content Table of Content 2 Maps 3 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Solving the Border Conflict 4 1.2 Contextualisation of the Problem 5 1.3 Research Question 5 1.4 Method, Material, Source Criticism and Limitations 6 2 Theory 8 2.1 Positive Peace 8 2.2 Distributive and Integrative Negotiations 10 2.3 Borders 10 2.4 Citizenship 11 2.5 Summary 12 3 Indians in Ecuador and Peru 13 3.1 Indians in the ‘War Zone’ 13 3.2 Indian Identity 15 3.3 Indian Demands 17 3.4 Indian Rights 19 3.4.1 ILO 169 19 3.4.2 Self Determination 21 3.5 Indian Social Movements 22 3.6 Summary 23 4 Border Conflict between Ecuador and Peru 24 4.1 The Conflict in 1995 24 4.2 Long-term Historical Background 26 4.3 The Conflict after the Rio Protocol 28 4.4 Ecuador and Peru’s Interests in the Conflict 29 4.5 Summary 31 5 Towards a Peace Agreement 31 5.1 Getting to the Negotiating Table 31 5.2 Four Guarantor Countries as Mediators 32 5.3 Negotiations become Integrative 35 5.4 Peace Agreement of 1998 37 5.5 Integration of the Indians in the Negotiations 39 5.6 Summary 42 6 Positive Peace Including Indians 42 6.1 Indians in the States 42 6.2 Positive Peace Building 44 6.3 Future of Positive Peace in Ecuador and Peru 46 6.4 Summary 46 7 Positive Peace With the Indians 47 References 49 3 Maps Map over the conflicting border line (Palmer 1997:120). -

Race, Fútbol, and the Ecuadorian Nation: the Ideological Biology of (Non-)Citizenship by Jean Muteba Rahier Florida International University

e-misférica 5.2: Race and its Others (December 2008) www.emisferica.org Race, Fútbol, and the Ecuadorian Nation: the Ideological Biology of (Non-)Citizenship By Jean Muteba Rahier Florida International University Whether new or old, cultural or biological, what … racisms have in common is their dependency on, and ultimate reduction to, a belief in the biological separation of the human population into visible and discrete groups; that is “race.” With the widespread belief that it is an open, autonomous and meritocratic arena, sport is fundamental in informing people’s perceptions about the naturalness and obviousness of racial difference. … The world of sport has thus become an image factory that disseminates and even intensifies our racial preoccupations. (Carrington and McDonald 2001: 4-5) Participation in international sports competitions often provides “national populations”— and particularly their elites—with occasions to enact the official understanding of “national identity,” or sometimes also to reflect upon and revisit what and who is included in, or excluded from, the “national character,” and why. Such events can also give a special stage to victorious athletes from subaltern groups or excluded peoples. This essay is focused on the comments published in the press and on the internet about the performance of the almost entirely black Ecuadorian national team at the 2006 FIFA World Cup—the biggest global sports arena there is. On 9 June 2006, the Ecuadorian team won 2-0 against Poland in their first match of the tournament in the Gelsenkirchen stadium in Germany. Two Afro-Ecuadorian players, Carlos Tenorio and Agustín (Tín) Delgado, marked the goals. -

PRATT-THESIS-2019.Pdf

THE UTILITARIAN AND RITUAL APPLICATIONS OF VOLCANIC ASH IN ANCIENT ECUADOR by William S. Pratt, B.S. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts with a Major in Anthropology August 2019 Committee Members: Christina Conlee, Chair David O. Brown F. Kent Reilly III COPYRIGHT by William S. Pratt 2019 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, William S. Pratt, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Numerous people have contributed over the years both directly and indirectly to the line of intrigue that led me to begin this work. I would like to extend thanks to all of the members of my thesis committee. To Christina Conlee for her patience, council, and encouragement as well as for allowing me the opportunity to vent when the pressures of graduate school weighed on me. To F. Kent Reilly for his years of support and for reorienting me when the innumerable distractions of the world would draw my eye from my studies. And I especially owe a great deal of thanks to David O. -

Food for Thought How Food and Economics Intersect in Rural Ecuador

Food For thought How Food and Economics Intersect in Rural Ecuador lindsay stone dietary trends can have large implications on public health. there is a strong physiological connection between food consumption and one’s well-being. thus nutrition is an important factor in a nation’s overall health. many factors contribute to how and why an individual eats certain foods. in ecuador, historical, socioeconomic, cultural, behavioral, and environmental factors influence the different diets, and thereby, the nutritional conditions, of different ethnic, and regional geographic populations. discrepancies among these groups are particularly noticeable in sierra, ecuador’s the highland region. this paper examines the prevalence of malnutrition across ecuador. specifically, it considers how the ecuadorian diet took shape, and how different sub-cuisines contribute to malnutrition. while all regions are considered, a focus is placed primarily on the sierra, given that levels of malnutrition are noticeably higher in this region, and that this highland area is home to large rural and indigenous communities who are most significantly impacted by the area’s nutritional conditions. Fried plantains, steamed tubers, spice-rubbed beef, that distinguish a given dish or food item as belonging to empanadas, sipping chocolate, flour tortillas… such is just specific categories; foods can be distinguished as belonging a sampling of the variety of foods and meals that can be to the “highland/lowland [or] north/central/south,” as found across the different geographical regions of Ecua- “urban/rural [or] “province/capital” fare, as stereotypically dor. This Latin American country spans from the Galapa- pre-Hispanic/Spanish-influenced or traditional/ gos Islands and the country’s Pacific coast to the Amazon indigenous/mestizo food, etc.