The Crime of Amateurism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application of the UAAA, RUAAA, and State Athlete-Agent Laws to Corruption in Men's College Basketball and Revisions Necessitated by NCAA Rule Changes

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 30 Issue 1 Fall Article 4 2019 Application of the UAAA, RUAAA, and State Athlete-Agent Laws to Corruption in Men's College Basketball and Revisions Necessitated by NCAA Rule Changes Joshua Lens Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Joshua Lens, Application of the UAAA, RUAAA, and State Athlete-Agent Laws to Corruption in Men's College Basketball and Revisions Necessitated by NCAA Rule Changes, 30 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 47 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol30/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LENS – ARTICLE 30.1 1/10/2020 11:59 AM APPLICATION OF THE UAAA, RUAAA, AND STATE ATHLETE-AGENT LAWS TO CORRUPTION IN MEN’S COLLEGE BASKETBALL AND REVISIONS NECESSITATED BY NCAA RULE CHANGES JOSHUA LENS* I. INTRODUCTION Opening statements in the October 2018 federal trial regarding corruption in men’s college basketball served as a juicy appetizer for what was to come in the rest of the trial. Now former Adidas executive James Gatto, former Adidas consultant Merl Code, and aspiring agent and former runner for NBA agent Andy Miller, Christian Dawkins, faced accusations that they paid money from Adidas to prospective student-athletes and their families to ensure the prospective student-athletes signed with Adidas-sponsored schools, and then with Adidas and certain financial planners and agents once they turned professional.1 In her opening statement, Casey Donnelly, Gatto’s attorney, admitted that Gatto funneled $100,000 to the family of highly recruited prospect Brian Bowen; paid $40,000 to the family of current Dallas Maverick Dennis Smith, Jr. -

Student-Athlete? an In-Depth Look at the Past, Present, and Future Kyle Elliott Lukf Er

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2018 Student-Athlete? An In-Depth Look at the Past, Present, and Future Kyle Elliott lukF er Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Sports Management Commons Recommended Citation Fluker, Kyle Elliott, "Student-Athlete? An In-Depth Look at the Past, Present, and Future" (2018). Senior Honors Theses. 602. https://commons.emich.edu/honors/602 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Student-Athlete? An In-Depth Look at the Past, Present, and Future Abstract The NCAA began in the early 1900s as a way to regulate the wild west that was intercollegiate athletics. Over time, the organization has grown from its 62 member beginnings to three divisions with 1,281 members. In 2017, for the first time in its history, the NCAA brought in over one billion dollars in total revenue (Kirshner 2018). The NCAA has been able to achieve this feat by its insistence on the "amateurism" of its participants. This business model has allowed the organization to keep the financial benefits associated with the playing of high-level sports on college campuses. Participants in these events deemed "Student-Athletes," are barred from receiving payment for their athletic skills without being faced with the potential of losing their ability to compete at the NCAA level. -

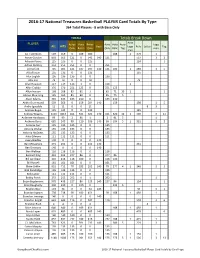

2016-17 National Treasures Basketball PLAYER Card Totals by Type 364 Total Players - 8 with Base Only

2016-17 National Treasures Basketball PLAYER Card Totals By Type 364 Total Players - 8 with Base Only TOTALS Totals Break Down Auto PLAYER Autos Auto Relics Auto Auto Auto Logo ALL HITS Base Logo Relic Letter Tag Only Relics Only Only Relic Tag man man A.J. Hammons 569 569 0 189 380 188 1 379 1 Aaron Gordon 803 663 121 0 542 140 121 537 3 2 Adreian Payne 125 125 0 0 125 124 1 Adrian Dantley 251 251 251 0 0 251 Al Horford 745 605 121 187 297 140 121 186 1 289 3 5 Al Jefferson 135 135 0 0 135 135 Alex English 136 136 136 0 0 136 Alex Len 79 79 0 0 79 79 Allan Houston 117 117 116 1 0 116 1 Allen Crabbe 376 376 251 125 0 251 125 Allen Iverson 168 168 85 82 1 85 71 10 1 1 Alonzo Mourning 165 165 85 80 0 85 75 5 Alvan Adams 345 345 135 210 0 135 210 Andre Drummond 503 363 0 159 204 140 159 198 1 5 Andre Iguodala 11 11 0 0 11 8 3 Andrew Bogut 135 135 0 0 135 135 Andrew Wiggins 1153 1013 161 331 521 140 161 320 10 1 507 3 11 Anfernee Hardaway 99 99 2 96 1 2 91 5 1 Anthony Davis 685 545 99 110 336 140 99 104 5 1 331 3 2 Antoine Carr 135 135 135 0 0 135 Antoine Walker 135 135 135 0 0 135 Antonio McDyess 135 135 135 0 0 135 Artis Gilmore 111 111 111 0 0 111 Avery Bradley 140 0 0 0 0 140 Ben McLemore 371 231 0 0 231 140 231 Ben Simmons 140 0 0 0 0 140 Ben Wallace 116 116 116 0 0 116 Bernard King 333 333 247 86 0 247 86 Bill Laimbeer 216 216 116 100 0 116 100 Bill Russell 161 161 161 0 0 161 Blake Griffin 852 712 78 282 352 140 78 277 4 1 346 3 3 Bob Dandridge 135 135 135 0 0 135 Bob Lanier 111 111 111 0 0 111 Bobby Portis 253 253 252 0 1 252 1 Bojan Bogdanovic 578 438 227 86 125 140 227 86 124 1 Brad Daugherty 230 230 0 230 0 225 5 Bradley Beal 174 34 0 0 34 140 30 3 1 Brandon Ingram 738 738 98 189 451 98 188 1 450 1 Brandon Jennings 140 0 0 0 0 140 Brandon Knight 643 643 116 0 527 116 518 3 6 Brandon Rush 4 4 0 0 4 4 Brice Johnson 640 640 0 189 451 188 1 450 1 Brook Lopez 625 485 0 0 485 140 479 6 Bryn Forbes 140 140 140 0 0 140 Buddy Hield 837 837 232 189 416 232 188 1 415 1 C.J. -

AUBURN BASKETBALL Adam Harrington/Eddie Johnson

Table of Contents 2012-13 AUBURN BASKETBALL Adam Harrington/Eddie Johnson ............ 115 Darrell Lockhart/John Mengelt ............... 116 2012-13 Quick Facts Table of Contents ........................................ 1 General Information Building a Winner ....................................2-3 Mike Mitchell/Chris Morris .................... 117 Mamadou N'diaye/Moochie Norris......... 118 School ............................ Auburn University Recruiting the Nation's Best ....................4-5 Location ........................... Auburn, Alabama Auburn Academic Support .......................6-7 Myles Patrick/Stan Pietkiewicz .............. 119 Founded .............................. October 1, 1856 Dribble Drive Offense ..............................8-9 Chuck Person/Wesley Person.................. 120 In Your Face Defense ...........................10-11 Chris Porter/Aaron Swinson ................... 121 Enrollment ......................................... 25,134 Be a Part of Something Special ...........12-13 AUBURN BASKETBALL Colors ............ Burnt Orange and Navy Blue AU & Tony Barbee...A New Beginning ...14-15 World Famous Fan Base ..................122-123 Nickname ........................................... Tigers The Auburn Family ..............................16-17 National Media Interest ....................124-125 Conference .............................. Southeastern Auburn University ...............................18-19 Prime-Time Exposure ......................126-127 Arena ......................... Auburn Arena (9,121) -

Official Basketball Box Score -- Game Totals -- Final Statistics Virginia Vs Duke 01/19/19 6:00 Pm at Cameron Indoor Stadium (Durham, N.C.)

Official Basketball Box Score -- Game Totals -- Final Statistics Virginia vs Duke 01/19/19 6:00 pm at Cameron Indoor Stadium (Durham, N.C.) Virginia 70 • 16-1,4-1 Total 3-Ptr Rebounds ## Player FG-FGA FG-FGA FT-FTA Off Def Tot PF TP A TO Blk Stl Min 25 Mamadi Diakite f 1-5 0-2 0-0 0 1 1 4 2 0 0 1 0 17 33 Jack Salt c 2-2 0-0 1-2 1 3 4 2 5 0 1 0 0 27 05 Kyle Guy g 6-12 2-7 0-0 2 4 6 1 14 1 1 0 1 37 11 Ty Jerome g 6-13 1-5 1-3 1 3 4 2 14 4 1 0 0 35 12 De'Andre Hunter g 8-14 0-2 2-4 1 3 4 3 18 0 1 0 1 38 00 Kihei Clark 1-2 0-0 0-0 0 1 1 2 2 1 2 0 1 18 02 Braxton Key 2-3 0-1 7-8 1 5 6 4 11 2 1 1 1 21 30 Jay Huff 2-2 0-0 0-0 0 1 1 2 4 0 1 2 0 7 Team 1 2 3 Totals 28-53 3-17 11-17 7 23 30 20 70 8 8 4 4 200 FG % 1st Half: 15-26 57.7% 2nd half: 13-27 48.1% Game: 28-53 52.8% Deadball 3FG % 1st Half: 1-8 12.5% 2nd half: 2-9 22.2% Game: 3-17 17.6% Rebounds FT % 1st Half: 1-3 33.3% 2nd half: 10-14 71.4% Game: 11-17 64.7% 2 Duke 72 • 15-2, 4-1 Total 3-Ptr Rebounds ## Player FG-FGA FG-FGA FT-FTA Off Def Tot PF TP A TO Blk Stl Min 01 Zion Williamson f 10-16 0-1 7-14 3 6 9 2 27 1 3 1 2 38 02 Cam Reddish f 3-12 1-6 2-4 1 7 8 4 9 1 4 0 2 37 05 RJ Barrett f 11-19 1-6 7-11 0 5 5 0 30 3 1 0 0 40 41 Jack White f 2-3 0-1 0-0 2 2 4 3 4 0 0 0 1 40 20 Marques Bolden c 0-0 0-0 2-2 2 2 4 4 2 0 0 0 0 33 12 Javin DeLaurier 0-0 0-0 0-0 0 0 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 7 15 Alex O'Connell 0-1 0-0 0-0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 5 Team 2 0 2 Totals 26-51 2-14 18-31 10 22 32 18 72 6 8 1 5 200 FG % 1st Half: 14-32 43.8% 2nd half: 12-19 63.2% Game: 26-51 51.0% Deadball 3FG % 1st Half: 2-10 20.0% 2nd half: 0-4 0.0% Game: 2-14 14.3% Rebounds FT % 1st Half: 7-9 77.8% 2nd half: 11-22 50.0% Game: 18-31 58.1% 5 Officials: Tim Clougherty,James Breeding,Jamie Luckie Technical fouls: Virginia-None. -

Los Angeles Lakers Staff Directory Los Angeles Lakers 2002 Playoff Guide

LOS ANGELES LAKERS STAFF DIRECTORY Owner/Governor Dr. Jerry Buss Co-Owner Philip F. Anschutz Co-Owner Edward P. Roski, Jr. Co-Owner/Vice President Earvin Johnson Executive Vice President of Marketing Frank Mariani General Counsel and Secretary Jim Perzik Vice President of Finance Joe McCormack General Manager Mitch Kupchak Executive Vice President of Business Operations Jeanie Buss Assistant General Manager Ronnie Lester Assistant General Manager Jim Buss Special Consultant Bill Sharman Special Consultant Walt Hazzard Head Coach Phil Jackson Assistant Coaches Jim Cleamons, Frank Hamblen, Kurt Rambis, Tex Winter Director of Scouting/Basketball Consultant Bill Bertka Scouts Gene Tormohlen, Irving Thomas Athletic Trainer Gary Vitti Athletic Performance Coordinator Chip Schaefer Senior Vice President, Business Operations Tim Harris Director of Human Resources Joan McLaughlin Executive Director of Marketing and Sales Mark Scoggins Executive Director, Multimedia Marketing Keith Harris Director of Public Relations John Black Director of Community Relations Eugenia Chow Director of Charitable Services Janie Drexel Administrative Assistant Mary Lou Liebich Controller Susan Matson Assistant Public Relations Director Michael Uhlenkamp Director of Laker Girls Lisa Estrada Strength and Conditioning Coach Jim Cotta Equipment Manager Rudy Garciduenas Director of Video Services/Scout Chris Bodaken Massage Therapist Dan Garcia Basketball Operations Assistant Tania Jolly Executive Assistant to the Head Coach Kristen Luken Director of Ticket Operations -

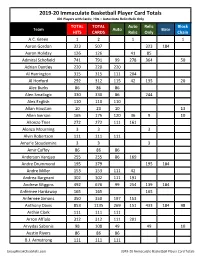

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals 401 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 1 2 1 1 Aaron Gordon 323 507 323 184 Aaron Holiday 126 126 41 85 Admiral Schofield 741 791 99 278 364 50 Adrian Dantley 220 220 220 Al Harrington 315 315 111 204 Al Horford 292 312 115 42 135 20 Alec Burks 86 86 86 Alen Smailagic 330 330 86 244 Alex English 110 110 110 Allan Houston 10 23 10 13 Allen Iverson 165 175 120 36 9 10 Allonzo Trier 272 272 111 161 Alonzo Mourning 3 3 3 Alvin Robertson 111 111 111 Amar'e Stoudemire 3 3 3 Amir Coffey 86 86 86 Anderson Varejao 255 255 86 169 Andre Drummond 195 379 195 184 Andre Miller 153 153 111 42 Andrea Bargnani 302 302 111 191 Andrew Wiggins 492 676 99 254 139 184 Anfernee Hardaway 165 165 165 Anfernee Simons 350 350 197 153 Anthony Davis 853 1135 269 151 433 184 98 Archie Clark 111 111 111 Arron Afflalo 312 312 111 201 Arvydas Sabonis 98 108 49 49 10 Austin Rivers 86 86 86 B.J. Armstrong 111 111 111 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bam Adebayo 163 347 163 184 Baron Davis 98 118 98 20 Ben Simmons 206 390 5 201 184 Bernard King 230 233 230 3 Bill Laimbeer 4 4 4 Bill Russell 104 117 104 13 Bill Walton 35 48 35 13 Blake Griffin 318 502 5 313 184 Bob McAdoo 49 59 49 10 Boban Marjanovic 264 264 111 153 Bogdan Bogdanovic 184 190 141 42 1 6 Bojan Bogdanovic 247 431 247 184 Bol Bol 719 768 99 287 333 -

THE NCAA NEWS/Janwy 23,19115 3 I I Legislative Assistance Women’S Championship Proposed 1985 Column No

The NC January 23,1985, Volume 22 Number 4 ()f&iaj Publicationof thw@ National Collegiate Athletic Association Davis, Bailey and Roaden named to top positions John R. Davis, faculty athletics Oregon. Prior to directing the experi- representative at Oregon State Uni- mental station, Davis was head of the versity who has served as secretary- agricultural engineering department treasurer of the NCAA the past two at Oregon State for four years. years, was named president of the From 1965 to 1971, Davis was Association January 16 during closing dean of the college of engineering and activities of the 79th annual Conven- architecture at the University of Ne- tion in Nashville, Tennessee. braska, Lincoln. Davis succeeds John L. Toner, Unii Davis, who served on the Council versity of Connecticut director of and Governmental Affairs Committee athletics, who concluded eight years prior to his appointment as secretary- of service in the NCAA administrative treasurer, was a lecturer at the Uni- structure-four years on the Council, versity of California, Davis, and was two years as secretary-treasurer and a member of the agricultural engi- two years as president. neering faculties at Purdue University Davis will serve as president for and Michigan State University. two years. He will be assisted by A native of Minnesota, Davis re- Wilford S. Bailey, Auburn University ceived bachelor’s and master’s degrees faculty athletics representative, who in agricultural engineering from the was elected secretary-treasurer. University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. Other Administrative Committee He later earned a Ph.D. in agricultural members who will serve in 1985 are engineering from Michigan State. -

"The NCAA Commission's Report and Recommendations on College Basketball

GOVERNANCE Ryan P. Mulvaney, Esq. Partner; NBPA certified basketball agent; FIBA licensed basketball agent [email protected] McElroy, Deutsch, Mulvaney & Carpenter, LLP, New Jersey The NCAA Commission’s report and recommendations on college basketball - some layups, some airballs On 11 October 2017, resulting from the arrests of numerous college coaches, Adidas representatives, and a recruiter for a now defunct sports agency in connection with the United States Attorney’s Ofce for the Southern District of New York’s (‘DOJ’) investigation into corruption in “the dark underbelly of college basketball1” - paying coaches, players and/or their families - the National Collegiate Athletic Association (‘NCAA’) President Mark Emmert announced the formation of the Commission On College Basketball (‘Commission’) to examine Division I basketball2. In this article, Ryan P. Mulvaney, Esq., Partner at McElroy, Deutsch, Mulvaney & Carpenter, LLP, provides his analysis of the resulting report and recommendations (‘R&R’) published by the Commission to address the issues in collegiate basketball in the US. Introduction when it comes to opining on monetarily Christian Dawkins of now defunct ASM In its R&R, the Commission noted rewarding players who are targeted by Sports, a financial advisor, Munish Sood, that those it interviewed not only Division I programs in grammar and high and a suit maker, Rashan Michel (‘Agent/ confirmed the DOJ’s allegations but school not for their academic prowess Advisor Defendants’);11 and an executive, highlighted concessions of actual but for their athleticism (ability to earn James Gatto, and representatives, knowledge: “everyone knew what universities and conferences money), Merl Code and Jonathan Augustine12, was going on3” and “many informed the Commission’s silence is deafening. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

2016 Usa Men's U18 National Team Training Camp

20162016 USAUSA BASKETBALLBASKETBALL MEN’SMEN’S U18U18 NATIONALNATIONAL TEAMTEAM TRAININGTRAINING CAMPCAMP MEDIAMEDIA GUIDEGUIDE JUNE 14-18, 2016 • COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO #USABMU18 • #USABFAMILY • @USABASKETBALL 2016 USA MEN’S U18 NATIONAL TEAM TRAINING CAMP @ U.S. OLYMPIC TRAINING CENTER @ STRAKE JESUIT HIGH SCHOOL • COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO • HOUSTON, TEXAS Tuesday, June 14 Monday, July 11 Practice @ 6 pm Practice @ 8 pm Wednesday, June 15 Tuesday, July 12 Practice @ 10 am Practice @ 10 am Practice @ 6 pm Practice @ 6 pm Thursday, June 16 Wednesday, July 13 Practice @ 8:30 am Practice @ 10 am Finalists Announcement @ Time TBD Practice @ 6 pm Practice @ 4:30 pm Thursday, July 14 Friday, June 17 Practice @ 10 am Practice @ 10 am Practice @ 6 pm Practice @ 4:30 pm Friday, July 15 Saturday, June 28 Practice @ 1:30 pm Practice @ 8:30 am NOTES: • All sessions are closed to the public. • Media must be credentialed to attend training camp. • Times listed are local. 2016 USA U18 NATIONAL TEAM TRAINING CAMP STAFF JUNIOR NATIONAL TEAM COMMITTEE USA BASKETBALL STAFF Jim Boeheim, Syracuse University (Chair) Jim Tooley, Executive Director/CEO Lorenzo Romar, University of Washington Craig Miller, Chief Media/Communications Officer Matt Painter, Purdue University Sean Ford, Men’s National Team Director Bob McKillop, Davidson College Bj Johnson, Men’s Assistant National Team Director Curtis Sumpter, Former USA National Team Member Ellis Dawson, National Team Operations Director (Athlete Representative) Caroline Williams, Communications Director -

Opponents Opponents

opponents opponents OPPONENTS opponents opponents Directory Ownership ................................................................Bruce Levenson, Michael Gearon, Steven Belkin, Ed Peskowitz, ..............................................................................Rutherford Seydel, Todd Foreman, Michael Gearon Sr., Beau Turner President, Basketball Operations/General Manager .....................................................................................Danny Ferry Assistant General Manager.........................................................................................................................................Wes Wilcox Senior Advisor, Basketball Operations .....................................................................................................................Rick Sund Head Coach .......................................................... Larry Drew (All-Time: 84-64, .568; All-Time vs Hornets: 1-2, .333) Assistant Coaches ............................................................. Lester Conner, Bob Bender, Kenny Atkinson, Bob Weiss Player Development Instructor ............................................................................................................................Nick Van Exel Strength & Conditioning Coach ........................................................................................................................ Jeff Watkinson Vice President of Public Relations .........................................................................................................................................TBD