The Return of Beauty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lady of Edgecliff

The Lady of Edgecliff Annie Peachman Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney Street art is a developing postmodern phenomenon with the profound capacity to challenge the cultural assumptions underpinning modernity and a modernist approach to art. Taking Bruno Dutot’s work, ‘The Lady of Edgecliff’, or ‘Oucha’ as a starting point, one can explore the cultural importance of street art, as it elucidates the contradictions inherent to contemporary society – which exists as a hybrid of both modernity and postmodernity. Postmodernism informs the way in which street art contests the prevalence of empiricism within modernity, which values technique over symbolic meaning and aesthetics. Street art simultaneously challenges the modernist notion of progress towards utopian ideals, often focusing more on dystopia and revisiting the past through the use of intertextuality, viewing the world as a simulacrum rather than as an absolute truth. In its total public accessibility, street art also challenges the notion of art as a commodity, as well as the modernist association of art with institutionalism, which positions the artist as a tradesperson, and the art world as a business. Yet with increasing numbers of acclaimed street artists shifting to exhibiting in galleries and accepting commissions for their work, the distinctions between postmodern and modern art are blurred. As such, street art reveals the enduring vestiges of modernity in contemporary culture, and thus questions how such ideas remain in conjunction with the ideas of postmodernism– suggesting that contemporary society is not unconditionally postmodern but instead exists as a hybridised culture, with interrelated and interdependent elements of both postmodernity and modernity central to our contemporary milieu. -

First Friday Mural Tour Featuring 20X21eug Mural Project Artists

First Friday Mural Tour featuring 20x21EUG Mural Project artists Meet at us 5:30pm at West Broadway and Charnelton for the start of the guided tour, led by Paul Godin of 20x21EUG Mural Project. 1 Telmo Miel - Shaw-Med (198 W Broadway) 2 Beau Stanton - McDonald Theatre (1010 Willamette St) 3 Hyuro - KIVA (125 W 11th Ave) 4 Hush - Falling Sky Brewing House (1334 Oak Alley) 5 Blek le Rat - Level Up Arcade (1290 Oak St) 6 JAZ - McDonald Theatre (1010 Willamette St) 7 Blek le Rat - Actor’s Cabaret (996 Willamette St) Dan Witz - Actor’s Cabaret (996 Willamette St) 8 Acidum Project - Cowfish (62 W Broadway) ? Dan Witz - Various installations around Downtown Eugene Artist Biographies: Telmo Miel - Netherlands* Artistic duo Telmo Pieper and Miel Krutzmann, known as Telmo Miel, balance somewhere between surreal and realistic rendering with an immense attention to detail and vivid color. Beau Stanton - Brooklyn/USA Stanton lives in Brooklyn, N.Y. and draws his inspiration for his big-wall art from historic ornamentation, religious iconography, and classical painting. He does everything from large-scale installations to stained glass, mosaics, and multimedia animations. Hyuro - Spain/Argentina* Hyuro is best known for her surrealist and sometimes whimsical approach. Her work embodies a sense of eerie playfulness by blending thematic issues of politics, nature, and feminine identity. Hush - United Kingdom* Hush’s style draws upon elements of Japanese influence, including anime and geishas. His approach combines traditional artistic techniques and street art style, creating a dynamic blend of graphic elements and abstract pop. 20x21eug.com *A sample of the artist’s work, not a 20x21 mural Blek le Rat - France* Known as one of the Godfathers of Stencil Art, Blek le Rat’s work has served as inspiration for artists like Banksy and Space Invader. -

Top 5 Bands Or Artists… Charlotte Gainsbourg, 5:55, Because Records

08 Open 48 A Celebration of Street Art Sara and Marc Schiller of the Wooster Collective 10 Tehran Graffiti on why they love street art 12 Spy 1: Joska 54 Pictoplasma New cities, new friends, new fairytales Tristan Manco sees if the characters are still at war 14 Spy 2: Adolf Gil Lights on leaves reveal the city 58 Oh Shit Venezuelan artist Alejandro Lecuna takes action 16 Inside Basementizid (Heilbron) 60 In Your Ear Flip 2 18 Cheaper Sneakers Music Marbury and the art of endorsement 62 In Your Eye 20 Skating the Great Wall Books A photo journal by Kevin Metallier 64 Show & tell 26 Squatting the White Cube Banksy in LA Bombing the Brandwagen 66 Show & tell 24 Rider Ink FriendsWithYou Bootleg Show Steven Gorrow 70 Show & tell 34 Illustrative Works Iguapop 3rd Birthday Exhibition - Kukula - Lucy Mclauchlan 70 Want It Products - Brooke Reidt 73 Got a name for it? 47 Sawn Off Tales The art of Vincent Gootzen F L I P 2 Creative action = active creation Lucy Mclauchlan Lucy Cover: Cover: Issue #11 Creative Director Garry Maidment [email protected] Editor in Chief Harlan Levey [email protected] Associate Editor Jason Horton [email protected] Art Director Tobias Allanson [email protected] Music Editor Florent de Maria fl [email protected] Production Manager Tommy Klaehn [email protected] Distribution Susan Hauser [email protected] Contributors Brooke Reidt, Logan Hicks, Christine Strawberry, Tristan Manco, Kukula, Joska, Sara and Marc Schiller, Kev M, Lucy Mclauchlan, Adolf Gil, the big ‘I’ in Iguagpop, David Gaffney, Steven Gorrow, Jorgy Bear, Street Player, Cyrus Shahrad, Guifari, Sergei Vutuc, Vincent Gootzen, Lecu, Timothy Leary once said that women who want to be a beautiful book and made us again regret our limited Sam Borkson, Cameron Bird, Nounouhau Collective, Nelson and Conny Neuner. -

With, on and Against Street Signs on Art Made out of Street Signs

SAUC - Journal V4 - N1 Changing times: Tactics With, On and Against Street Signs On Art Made out of Street Signs Mª Isabel Carrasco Castro Marist College Madrid Program C/ Madrid, s/n Ofce: 9.0.40 Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Getafe, Spain [email protected] Abstract In The Practice of Everyday Life (1980), Michel de Certeau suggests the idea of a city in which there are, on one side, strategies of information, surveillance, control and infrastructure design laid out by the system and, on the other one, tactics defning the how-to-do of the users with regards to that system, that is, the operations by which they adapt them to align their own interests and needs. The texts allows us to examine the interventions of urban artists as a tactic characterized, as defned by De Certeau, as the harnessing of the system's resources (making do). This is more specifcally translated into adaptability, development on a space they do not own, identifcation and utilization of the occasion (time) and the inventiveness of diverting time and resources (shortcut and la perruque). In this work, we will take trafc signs of restriction and prohibition as one of the urban components that highlight the normativization of public spaces through the direct message of "NO" (not doing). Many artists have, in previous years, developed an interest in the artistic and symbolic possibilities of these signs and have developed works (tactics) as their response to them. Dan Witz (Chicago, 1957), Clet (Bretagne, 1966), Brad Dowey (Louisville, 1980) or DosJotas (Madrid, 1982) are good examples of this. -

Street Art Icon Daleast Paints Façade of Bülowstrasse 7

PRESS INFORMATION Page 1/3 Golden Eagle: Street Art Icon DALeast Paints Façade of Bülowstrasse 7 Der goldene Adlerkopf, gesprüht von DALeast, auf der Fassade der Bülowstr. 7. Photo: Henrik Haven Berlin, 29 October 2014: anyone who passes Nollendorfplatz on the subway or takes a stroll down Bülowstrasse in Schöneberg cannot miss the astonishing paint job on the commercial and residential property at number 7. Since just a few days ago, the entire façade has been covered in hundreds of golden lines. They criss-cross – and appear to the observer like a giant, three-dimensional and very much living Eagle-Head. The artwork was created by none less than the street art icon DALeast. The Chinese artist’s murals have been fascinating passers-by all over the world for several years now. DALeast came up with a particularly spectacular idea for Bülowstrasse: this time, he worked in yellow and white on black. A première. The art action is part of the “Project/M” series by the Gewobag initiative Urban Nation. Four times a year, Urban Nation invites a group of young, internationally renowned street artists to redesign surfaces in Bülowstrasse. “Project/M is about bringing artists together and letting them jointly develop lively and colourful artworks”, explains Yasha Young, director of the Urban Nation initiative and of Gewobag’s art and culture management. The shop windows on the ground floor of Bülowstrasse 7 also got a face lift. Last Saturday, the Americans Jeff Soto and Dan Witz, Switzerland’s NYCHOS, the Polish-born OLEK and the Mexican SANER each transformed one of the windows into an individual work of art, with the result that by the end of the evening, a spectacular outdoor gallery had been created. -

Acu.1203.Cor

Fall/Winter 2010 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art atCooper 2 | The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Message from Union President George Campbell Jr. At Cooper Union Autumn at The Cooper Union is always an exciting time, not least Fall/Winter 2010 because the season marks the arrival each year of our new incom- ing class of students. Their presence year after year renews the commitment and resolve of our faculty and staff to sustain the Message from the President 2 college’s standard of excellence that ranks Cooper Union among News Briefs 3 College Rankings the nation’s top institutions of higher education. These newly LEED Certification arrived undergraduates will be the second class of students to Presidential Search Update commence their studies at 41 Cooper Square, opened officially in Charitable Gift Annuities at The Cooper Union September of last year. Since its completion and integration into J. Hoberman first Gelb Professor in the Humanities The Cooper Union campus, the building has received significant Alumni on Wall Street Panel international media attention from the architectural and popular In Memory of Ysrael Seinuk press. Its design has been reviewed in countless print and elec- In Memory of Jane Deed tronic publications around the world. Most recently, the building Juliana Thomas has been recognized for its structurally integrated ecological Urban Visionaries Awards Dinner 6 profile and robust green features with the prestigious LEED Platinum certification, making 41 Cooper Square the first aca- Features 8 demic building in New York City to receive such an honor. -

Adam Friedman – “Space and Time, and Other Mysterious Aggregations” @ Eleanor Harwood Gallery

Search... HOME FEATURES STUDIO VISITS INTERVIEWS FAIRS STREETS VIDEOS BLOGS FORUM SOCIAL ABOUT Preview: Adam Friedman – “Space and Time, and Other Mysterious Aggregations” @ Eleanor Harwood Gallery Posted by sleepboy, January 22, 2013 Like 12 Tweet Arrested Motion Like 49,062 people like Arrested Motion. Facebook social plugin POPULAR POSTS Today This week This month Shepard Fairey x Lance Armstrong Mural @ Nike’s Montalban Upcoming: Jean-Michel Basquiat @ Gagosian With the opening set for January 26th at the Eleanor Harwood Gallery, the time is right to preview Adam (New York) Friedman’s newest body of work. Space and Time, and Other Mysterious Aggregations will feature the Portland-based artist’s signature surreal geologic forms, created through the process and painting and mixed media work. He describes his imagery thusly – “I paint symbols and tropes that we comprehend as landscape; mountains, sunsets, etc. But I Openings: “Nocturnes: Romancing the Night” @ relish the mystery of the natural world, and I’m curious what happens when we view nature through a lens that breaks National Arts Club the rules of our understanding. In my work, rules of perspective, distance, and light are bent. Space can become a solid object and places are folded on top of one another. Millions of years are compacted into a single instant and rocks Releases: Swoon – “Thalassa” @ Paper Monster become fluid. I strive to present a moment that defies human intervention in the landscape, and pays homage to the potential in the inexplicable.” Preview: Art Stage Singapore Discuss Adam Friedman here. Via Hi-Fructose. Streets: Mantis (not Banksy) Viewpoints: Top 25 Most Expensive Banksy Works Ever Studio Visits Takashi Murakami x Hajime Asaoka Watch Openings: Tim Biskup – “Excavation” @ Antonio Colombo SEARCH Search CALENDAR 1.08 : Writers and Writers @ MoMA (NY) 1.09 : James Jean @ Jack Tilton (NY) 1.09 : Jose Parla @ The Barclays Center (NY) 1.10 : Robert Lazzarini @ Marlborough Chelsea (NY) 1.10 : David Shrigley @ Anton Kern (NY) 1.10 : Liu Bolin @ Galerie Paris-Beijing (Paris) 1.11 : .. -

Exhibition Guide

HA HA ROAD 12 August – 23 October 2011 QUAD Gallery Guide Gallery Guide produced for the exhbition: HA HA ROAD at QUAD Gallery, Derby, England from 12 August – 23 October, 2011. Exhibition co-produced with Oriel Mostyn Gallery, Llandudno, Wales. Mostyn dates: 3 December – 8 January, 2011. Text copyright Dave Ball + Sophie Springer, 2011. All images copyright the respective artists/galleries. IMAGE FRONT COVER: Ha-Ha Road, Woolwich, London Courtesty of Nick Constantine, 2009 H A H A R O A D 12 August to 23 October 2011 Exploring the use of humour in contemporary art, Ha Ha Road presents the work of 25 international artists who play with a "rupture of sense". Taking its title from the name of a street, the exhibition plays on its double meaning. Apart from its connection with laughter, a "ha-ha" also refers to a type of sunken boundary: a wall or fence set into a trench, forming a hidden division in a landscape whilst preserving the scenic view. This invisible frontier serves as a neat metaphor for our relationship to the world of laughter. Strangely indistinguishable from the familiar terrain of normality, a joke transports us to a place where sense breaks down, where the familiar is turned on its head, where the ordinary becomes extraordinary, and where the world means differently. Nothing has changed and yet everything has changed. This is the paradoxical condition of humour, and the source of its disruptive power. The show explores what it means to step over this barrier and to set foot into the inexplicable and illogical world of humour. -

Download Map

12. Matt Small (United Kingdom) 20x21 Mural Project A British artist who focuses primarily on creating portraits, Small diverges from the classic painter as he creates his three dimensional portraits from reclaimed MURALPROJECT 20x21 ARTISTS and found items from the community. 13. WK Interact (France/USA) 1. Acidum Project (Brazil) Originally from France, WK has lived and worked in New York since the early The art duo of Robézio Marqs and Tereza Dequinta brought vivid color, 1990s. WK’s stunning black and white portrait of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. brilliant patterns and obscure characters to Eugene with “Sidewalk Games depicts a moment from his most famous speech. (and Kindness)”. 14. Alexis Diaz (Puerto Rico) 2. Beau Stanton (USA) Diaz is a painter and urban muralist known for his mythic and dreamlike A multi-disciplinary artist from Brooklyn, N.Y., Stanton draws inspiration depictions of animals in a state of metamorphosis. Painted with sumi ink and for his big-wall art from historic ornamentation, religious iconography brushes, this mammoth mural was “discovered” in the Whiteaker neighborhood and classical painting. in 2018. 3. Steven Lopez (USA) 15. Bayne Gardner (Eugene, Oregon, USA) The UO graduate returned to Eugene to provide a subtle environmental A self-taught visual artist living and working in the Eugene-Springfield area, message through his mural about the important role bees play in our Gardner is inspired by motion in nature and brings a lively and spontaneous food supply. energy to everything he paints. 4. Hua Tunan (China) 16. AIKO (Japan/USA) Tunan’s style of traditional Chinese art combined with Western graffiti Acclaimed street artist AIKO was born and raised in Tokyo before moving to depicts an epic battle between a dragon and tigers taking place among New York City in the mid-1990s. -

2013-2014 Annual Report Table of Contents

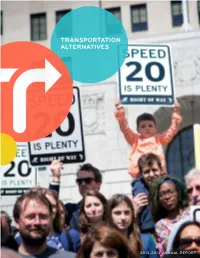

2013-2014 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 5 PAUL STEELY WHITE THE BIG IDEA: VISION ZERO 6 STOPPING THE SPEEDING EPIDEMIC 8 AUTOMATED ENFORCEMENT CAMERAS 10 NEW YORK CITY’S SPEED LIMIT 12 HAZARDOUS ARTERIAL STREETS 14 MANHATTAN 15 BRONX 16 QUEENS 17 STATEN ISLAND 18 BROOKLYN 19 MILESTONES 20 FINANCIAL INFORMATION 23 SUPPORTERS 24 2 TRANSPORTATION ALTERNATIVES IS YOUR ADVOCATE Transportation Alternatives’ mission is to reclaim New York City’s streets from the automobile and promote bicycling, walking and public transit as the best transportation alternatives. Since 1973, the hard work and passion of Transportation Alternatives advocates, members and activists have transformed the streets of New York City. BY THE NUMBERS 16,500 bicyclists riding five annual 12,000 bike tours dues-paying members 108,000 1,000 local activists online organizing in advocates five boroughs 48,000 petition signatures and letters sent to New York City and state officials in 365 days TRANSPORTATION ALTERNATIVES 2013-2014 ANNUAL REPORT 3 At a City Hall rally to demand the protection of pedestrians’ and bicyclists’ right of way, Transportation Alternatives Executive Director Paul Steely White stands with Greg Thompson, whose 16-year-old sister Renee was struck and killed by a truck driver in a Manhattan crosswalk. 4 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DEAR FRIENDS, MEMBERS AND SUPPORTERS very day I open the paper to another story of a New Yorker killed crossing the street. Every 30 hours in our city, another pedestrian’s life is lost. E In the face of such staggering violence, there is the reason for everything Transportation Alternatives does. -

SØREN SOLKÆR: SURFACE BOOK and EXHIBITION PROJECT All The

SØREN SOLKÆR: SURFACE BOOK AND EXHIBITION PROJECT All the portraits in SURFACE show artists who work in the public space. It is a book and exhibition project that was started in August 2012. The artists are photographed in cities across the world with their own art work , in a subjective and staged manner using artificial light and often props and masks. The resulting portrait aims to investigate the relation between the artist and his work and its space in the urban environment. The aim is to portray the most significant figures in public and street art both on the contemporary scene as well as the pioneering figures. The book will be published in February 2015, followed by numerous exhibitions worldwide. So far, I have photographed more than 110 artists , in locations stretching the globe – including Copenhagen, Stavanger, London, Miami, Newcastle, Paris, Berlin, New York, Los Angeles, Berlin, Sydney and Melbourne. SURFACE is an interpretation of the genre as well as the personalities behind the art itself. It is my ambition to present a snapshot of the scene in its current days of transition, whilst also shedding light on the pioneering figures who paved the way. SURFACE isn’t meant as documentation of street art but as is common in my approach, I photograph the artists in a visual interplay with their work, which consequently facilitate evidence of the art works themselves. SURFACE – THE BOOK The book will be a 248 page hardcover coffee table book measuring 24x32 cm, featuring around 140 artists. It will be published by Gingko Press in February 2015 and distributed worldwide. -

Dan Witz Press Release

Dan Witz Dark Doings November 5 – December 3, 2009 Opening Reception: Thursday, November 5th, 2009 "It was Dan Witz who, back in 2003, first showed us how powerful street art could be. Each summer Dan's projects take street art to new levels by adding elements of "surprise and delight" into the city landscape. For us, Dan Witz is the consummate street artist. He's provocative. He's dedicated. And most of all – He has absolutely wicked skills." – Marc and Sara Schiller Wooster Collective Carmichael Gallery is proud to present Dark Doings, a solo exhibition of new works by Dan Witz. This is the Brooklyn based artist’s first US west coast solo exhibition. In Dark Doings, Witz will showcase a selection of pieces from his expansive summer street project of the same name. Created both for the street and gallery, the subtle, haunting images of human and animal faces trapped behind dirty glass windows are inspired by a recent visit earlier in the year to the red light district of Amsterdam. In speaking about the philosophy behind this body of work, Dan explains, “I’m trying to exploit our collective tendency towards sleepwalking by inserting outrageous things right out there in plain view that are also practically invisible. My goal is to make obvious in your face art that ninety‐nine percent of the people who walk by won’t notice. Eventually when they stumble upon one or find out about it I’m hoping they’ll start wondering what else they’ve been missing.” Artwork at the show will comprise of mixed media on digital prints on plastic, presented either framed or mounted to wood doors, the latter serving as both canvas and contextual framework through which the work can be viewed.