BENSON, ALAN, Ph.D. Collaborative Authoring and the Virtual Problem of Context in Writing Courses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Analysis an Interdisciplinary Forum on Folklore and Popular Culture

CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Vol. 17.1 Cover image courtesy of Beate Sløk-Andersen CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Vol. 17.1 © 2019 by The University of California Editorial Board Pertti J. Anttonen, University of Eastern Finland, Finland Hande Birkalan, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey Charles Briggs, University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. Anthony Bak Buccitelli, Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg, U.S.A. Oscar Chamosa, University of Georgia, U.S.A. Chao Gejin, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Valdimar Tr. Hafstein, University of Iceland, Reykjavik Jawaharlal Handoo, Central Institute of Indian Languages, India Galit Hasan-Rokem, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem James R. Lewis, University of Tromsø, Norway Fabio Mugnaini, University of Siena, Italy Sadhana Naithani, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Peter Shand, University of Auckland, New Zealand Francisco Vaz da Silva, University of Lisbon, Portugal Maiken Umbach, University of Nottingham, England Ülo Valk, University of Tartu, Estonia Fionnuala Carson Williams, Northern Ireland Environment Agency Ulrika Wolf-Knuts, Åbo Academy, Finland Editorial Collective Senior Editors: Sophie Elpers, Karen Miller Associate Editors: Andrea Glass, Robert Guyker, Jr., Semontee Mitra Review Editor: Spencer Green Copy Editors: Megan Barnes, Jean Bascom, Nate Davis, Cory Hutcheson, Alice Markham-Cantor, Anna O’Brien, Joy Tang, Natalie Tsang Website Manager: Kiesha Oliver Table of Contents -

Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON

THEATER EMORY A Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON Three Productions in Rotating Repertory The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity October 23-24, November 3-4, 8-9 • Written by Kristoffer Diaz • Directed by Lydia Fort A satirical smack-down of culture, stereotypes, and geopolitics set in the world of wrestling entertainment. Mary Gray Munroe Theater We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Südwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 October 25-26, 30-31, November 10-11 • Written by Jackie Sibblies Drury • Directed by Eric J. Little The story of the first genocide of the twentieth century—but whose story is actually being told? Mary Gray Munroe Theater The Moors October 27-28, November 1-2, 6-7 • Written by Jen Silverman • Directed by Matt Huff In this dark comedy, two sisters and a dog dream of love and power on the bleak English moors. Mary Gray Munroe Theater Sara Juli’s Tense Vagina: an actual diagnosis November 29-30 • Written, directed, and performed by Sara Juli Visiting artist Sara Juli presents her solo performance about motherhood. Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Tatischeff Café April 4-14 • Written by John Ammerman • Directed by John Ammerman and Clinton Wade Thorton A comic pantomime tribute to great filmmaker and mime Jacques Tati Mary Gray Munroe Theater 2 2017-2018 SEASON Midnight Pillow September 21 - October 1, 2017 • Inspired by Mary Shelley • Directed by Park Krausen 13 Playwrights, 6 Actors, and a bedroom. What dreams haunt your midnight pillow? Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Anointing of Dracula: A Grand Guignol October 26 - November 5, 2017 • Written and directed by Brent Glenn • Inspired by the works of Bram Stoker and others. -

A Good Soldier Or Random Exposure? a Stochastic Accumulating Mechanism to Explain Frequent Citizenship

A GOOD SOLDIER OR RANDOM EXPOSURE? A STOCHASTIC ACCUMULATING MECHANISM TO EXPLAIN FREQUENT CITIZENSHIP By Christopher R. Dishop A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Psychology—Doctor of Philosophy 2020 ABSTRACT A GOOD SOLDIER OR RANDOM EXPOSURE? A STOCHASTIC ACCUMULATING MECHANISM TO EXPLAIN FREQUENT CITIZENSHIP By Christopher R. Dishop The term, “good soldier,” refers to an employee who exhibits sustained, superior citizenship relative to others. Researchers have argued that this streaky behavior is due to motives, personality, and other individual characteristics such as one’s justice perceptions. What is seldom acknowledged is that differences across employees in their helping behavior may also reflect differences in the number of requests that they receive asking them for assistance. To the extent that incoming requests vary across employees, a citizenship champion could emerge even among those who are identical in character. This study presents a situation by person framework describing how streaky citizenship may be generated from the combination of context (incoming requests for help) and person characteristics (reactions to such requests). A pilot web-scraping study examines the notifications individuals receive asking them for help. The observed empirical pattern is then implemented into an agent-based simulation where person characteristics and responses can be systematically controlled and manipulated. The results suggest that employee helping behaviors, in response to pleas for assistance, may exhibit sustained differences even if employees do not differ a priori in motive or character. Theoretical and practical implications, as well as study limitations, are discussed. I dedicate this dissertation to four family members who made my education possible. -

Between the Grimms and "The Group" -- Literature in American High

R EPOR T R ESUMES ED 015 175 TE 000 039 BETWEEN THE GRIMMS AND "THE GROUP"--LITERATURE IN AMERICAN HIGH SCHOOLS. DY- ANDERSON, SCARVIA D. EDUCATICWAL TESTING SERVICE, PRINCETON, N.J. PUB DATE AFR 64 EDRS FRICE MF-$0.25 HC-$1.00 23F. DESCRIPTORS- *ENGLISH INSTRUCTION, *LITERATURE, *SECONDARY EDUCATION, BIOGRAPHIES, DRAMA, ENGLISH CURRICULUM, ESSAYS, NOVELS, POETRY, SHORT STORIES, EDUCATIONAL TESTING SERVICE, IN 1963, THE COOPERATIVE TEST DIVISION OF THE EDUCATIONAL TESTING SERVICE SOUGHT TO ESTABLISH A LIST OF THE MAJOR WORKS OF LITERATURE. TAUGHT TO ALL STUDENTS IN ANY ENGLISH CLASS IN UNITED STATES SECONDARY SCHOOLS. QUESTIONNAIRES ASKING FOR SUCH A LIST OF EACH GRADE WERE SENT TO RANDOM SAMPLES OF SCHOOLS, AND 222 FUDLIC, 223 CATHOLIC, 192 INDEPENDENT, AND 54 SELECTED URBAN SCHOOLS RESPONDED. MAJOR RESULTS SHOW THAT THE FOLLOWING WORKS ARE TAUGHT IN AT LEAST 30 PERCENT 0F THE PUBLIC SECONDARY SCHOOLS FROM WHICH RESPONSES WERE RECEIVED--"MACDETHI" "JULIUS CAESAR," "SILAS MARNER," "OUR TOWN," "GREAT EXPECTATIONS," "HAMLET," "RED BADGE OF COURAGE," "TALE OF TWO CITIES," AND "THE SCARLET LETTER." THE WORKS TAUGHT IN AT LEAST 30 PERCENT OF THE CATHOLIC SECONDARY SCHOOLS ARE THOSE LISTED FOR PUBLIC SCHOOLS PLUS "FRICE AND PREJUDICE" AND "THE MERCHANT 07 VENICE." THE INDEFENDENT SCHOOL LIST INCLUDES ALL TITLES ON THE OTHER TWO LISTS WITH THE EXCEPTION OF "OUR TOWN," AND THE ADDITION OF "HUCKLEBERRY FINN," "THE ODYSSEY," "OEDIPUS THE KING," "ROMEO AND JULIET," AND "RETURN OF THE NATIVE." (THE BULK OF THE REPORT CONTAINS (1) PERCENTAGE TABLES AND LISTS OF MAJOR WORKS ASSIGNED BY FIVE PERCENT OR MORE OF THE SECONDARY SCHOOLS SURVEYED, (2) A DESCRIPTION OF THE SAMPLE SCHOOLS, AND (3) A LIST OF WORKS USED IN LESS THAN FIVE PERCENT OF SCHOOLS IN ANY OF THE SAMPLES.) (DL) • LITERATURE IN AMERICAN HIGH SCHOOLS Scarvia B. -

There Goes 'The Neighborhood'

NEED A TRIM? AJW Landscaping 910-271-3777 September 29 - October 5, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching Licensed – Insured – FREE Estimates 00941084 The cast of “The Neighborhood” Carry Out WEEKDAYMANAGEr’s SPESPECIALCIAL $ 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Pizzas5 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5and 16EACH oz. Beverage (AdditionalMonday toppings $1.40Thru each) Friday There goes ‘The from 11am - 4pm Neighborhood’ 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, September 29, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Comedy with a purpose: It’s a beautiful day in ‘The Neighborhood’ By Kyla Brewer munity. Calvin’s young son, Marty The cast shuffling meant the pi- TV Media (Marcel Spears, “The Mayor”), is lot had to be reshot, and luckily the happy to see Dave, his wife, Gem- cast and crew had an industry vet- t the end of the day, it’s nice to ma (Beth Behrs, “2 Broke Girls”), eran at the helm. Legendary televi- Akick back and enjoy a few and their young son, Grover (Hank sion director James Burrows, best laughs. Watching a TV comedy is a Greenspan, “13 Reasons Why”). known for co-creating the TV classic great way to unwind, but some sit- Meanwhile, Calvin’s older unem- “Cheers,” directed both pilots for coms are more than just a string of ployed son, Malcolm (Sheaun McK- “The Neighborhood.” A Hollywood snappy one-liners. A new series inney, “Great News”), finds it enter- icon, he’s directed more than 50 takes a humorous look at a serious taining to watch his frustrated fa- television pilots, and he reached a issue as it tackles racism in America. -

ENG 402: Advanced Placement English Literature & Composition Summer Reading

ENG 402: Advanced Placement English Literature & Composition Summer Reading Dear students, Welcome to Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition! You have chosen a challenging, but rewarding path. This course is for students with intellectual curiosity, a strong work ethic, and a desire to learn. I know all of you have been well prepared for the “Wonderful World of Literature” in which we will delve into a wide selection of fiction, drama, and poetry. In order to prepare for the course, you will complete a Summer Reading Assignment prior to returning to school in the fall. Your summer assignment has been designed with the following goals in mind: to help you build confidence and competence as readers of complex texts; to give you, when you enter class in the fall, an immediate basis for discussion of literature – elements like narrative viewpoint, symbolism, plot structure, point of view, etc.; to set up a basis for comparison with other works we will read this year; to provide you with the beginnings of a repertoire of works you can write about on the AP Literature Exam next spring; and last but not least, to enrich your mind and stimulate your imagination. If you have any questions about the summer reading assignment (or anything else pertaining to next year), please feel free to email me ([email protected]). I hope you will enjoy and learn from your summer reading. I am looking forward to seeing you in class next year! Have a lovely summer! Mrs. Yee Read: How to Read Literature Like a Professor by Thomas C. -

For the Duration: Global War and Satire in England and the United States

FOR THE DURATION: GLOBAL WAR AND SATIRE IN ENGLAND AND THE UNITED STATES by Elizabeth Steedley A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland February 2015 ABSTRACT “For the Duration” moves to unsettle some regnant assumptions about the ways in which historical experience shaped the formal choices and political investments of modernist writers. While recent critical work has focused on the influence of the Great War either on non-combatant authors or on minor memoirists and poets of the trenches, little attention has been given to the war’s effect on modernist authors who saw combat and thereafter crafted narratives distinguished by their satirical innovation. In the first three chapters of this dissertation, I concentrate on works by Ford Madox Ford, Wyndham Lewis, and Evelyn Waugh to suggest that these soldier-authors’ experience of temporal duration in war led them not, as one might expect, to emphasize Bergsonian durée in the novelistic presentation of experience but rather to reject it. Concerned that Bergsonism and its literary offshoots offered no foothold for critical engagement with post- war reality, these writers dwelt on the importance of clock-time, causality, and material reality in providing a grounding for historical responsibility; moreover, they strove to exploit the political potential of satire, a genre that has a peculiarly temporal character. Satire was especially attractive to these writers, I argue, not only because they saw in the interwar world a dispiriting unconcern with the causes and consequences of World War I but also because the genre’s dependence on barbed, multi-front attacks mimicked a key feature of modern combat. -

Penguin Classics

PENGUIN CLASSICS A Complete Annotated Listing www.penguinclassics.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world, providing readers with a library of the best works from around the world, throughout history, and across genres and disciplines. We focus on bringing together the best of the past and the future, using cutting-edge design and production as well as embracing the digital age to create unforgettable editions of treasured literature. Penguin Classics is timeless and trend-setting. Whether you love our signature black- spine series, our Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions, or our eBooks, we bring the writer to the reader in every format available. With this catalog—which provides complete, annotated descriptions of all books currently in our Classics series, as well as those in the Pelican Shakespeare series—we celebrate our entire list and the illustrious history behind it and continue to uphold our established standards of excellence with exciting new releases. From acclaimed new translations of Herodotus and the I Ching to the existential horrors of contemporary master Thomas Ligotti, from a trove of rediscovered fairytales translated for the first time in The Turnip Princess to the ethically ambiguous military exploits of Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, there are classics here to educate, provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers of all interests and inclinations. We hope this catalog will inspire you to pick up that book you’ve always been meaning to read, or one you may not have heard of before. To receive more information about Penguin Classics or to sign up for a newsletter, please visit our Classics Web site at www.penguinclassics.com. -

GLOBAL EXAMPLES of FORBIDDEN BOOKS for The

documenta 14 The Parthenon of Books by Marta Minujín Global Examples of Forbidden Books GLOBAL EXAMPLES OF FORBIDDEN BOOKS For the artwork The Parthenon of Books, part of documenta 14 in Kassel, the artist Marta Minujín and documenta 14 are collecting up to 100.000 books which have been re-published after being banned for years as well as those that are distributed legally in some countries but not in others. The following list of currently or formerly prohibited books, many of which are considered among the classics of world literature today, illustrates the global scope of censorship. The donated books do not necessarily need to be original editions from the time of their respective prohibitions. documenta 14 welcomes donations of new editions, original editions, as well as several copies of the same title. Akhmatova, Anna Andreyevna: Poems 1909–1945 Aristophanes: Lysistrata Balzac, Honoré de: A Woman of Thirty Balzac, Honoré de: The Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans or A Harlot High and Low Balzac, Honoré de: The Girl with the Golden Eyes Balzac, Honoré de: A Murky Business Balzac, Honoré de: History of the Thirteen Balzac, Honoré de: Droll Stories Balzac, Honoré de: Eugénie Grandet Balzac, Honoré de: The Old Maid or An Old Maid Balzac, Honoré de: The Country Doctor Balzac, Honoré de: The Unknown Masterpiece Beecher Stowe, Harriet: Uncle Tom’s Cabin The Bible Boccaccio, Giovanni: The Decameron Burroughs, William S.: Naked Lunch Brecht, Bertolt: Entire works Brod, Max: Entire works Brodsky, Joseph Aleksandrovich: Entire works Brown, -

The Werewolf in Lore and Legend Plate I

Montague Summers The Werewolf IN Lore and Legend Plate I THE WARLOCKERS’ METAMORPHOSIS By Goya THE WEREWOLF In Lore and Legend Montague Summers Intrabunt lupi rapaces in uos, non parcentes gregi. Actus Apostolorum, XX, 29. DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. Mineola New York Bibliographical Note The Werewolf in Lore and Legend, first published in 2003, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1933 by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., London, under the title The Werewolf. Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Summers, Montague, 1880-1948. [Werewolf] The werewolf in lore and legend / Montague Summers, p. cm. Originally published: The werewolf. London : K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1933. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-486-43090-1 (pbk.) 1. Werewolves. I. Title. GR830.W4S8 2003 398'.45—dc22 2003063519 Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc., 3 1 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501 CONTENTS I. The Werewolf: Lycanthropy II. The Werewolf: His Science and Practice III. The Werewolf in Greece and Italy, Spain and Portugal IV. The Werewolf in England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland V. The Werewolf in France VI. The Werewolf in the North, in Russia and Germany A Note on the Werewolf in Literature Bibliography Witch Ointments. By Dr. H. J. Norman Index LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS I. The Warlocks’ Metamorphosis. By Goya. Formerly in the Collection of the Duke d’Osuna II. A Werewolf Attacks a Man. From Die Emeis of Johann Geiler von Kaisersberg III. The Transvection of Witches. From Ulrich Molitor’s De Lamiis IV. The Wild Beast of the Gevaudan. -

Conference Program

Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church In the Currents of History: from Trent to the Future Mission Statement Welcome to the Beautiful City of Trento! And Thank You for Making this Journey! Since moral theology is so diffuse today, since many Catholic theological ethicists Here the Council of Trent convened time and again for twenty-five years, from December are caught up in their own specific cultures, and since their interlocutors tend to be 13, 1545 to December 4, 1563. Here we meet for only 4 days! in other disciplines, there is the need for an international exchange of ideas among Catholic theological ethicists. When the Council Fathers created the field of moral theology for seminary formation, they could not have imagined who would be teaching theological ethics five centuries Catholic theological ethicists recognize the need: to appreciate the challenge of later. But here we are today, from more than 70 countries, lay women and men, religious pluralism; to dialogue from and beyond local culture; and to interconnect within a women and men, and clergy. world church not dominated solely by a northern paradigm. We have much to do. While we can learn from the past, we need to keep our eyes In response to these recognized needs, Catholic theological ethicists will meet to on the future. With technology in a globalized world, we do not need to journey refresh their memories, reclaim their heritage, and reinterpret their sources. here again and again as the Council Fathers did. Rather, with the same dedication, imagination, and hope that animated them, together we need to develop sustained Therefore, Catholic theological ethicists will pursue in this conference a way of modes of networking so as to better serve the church and the world by pursuing the proceeding that reflects their local cultures and engages in cross-cultural conversations truth in justice and charity. -

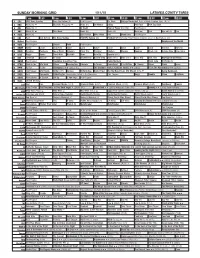

Sunday Morning Grid 1/11/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/11/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Dr. Chris College Basketball Duke at North Carolina State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) On Money Skiing PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football NFC Divisional Playoff Dallas Cowboys at Green Bay Packers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Employee of the Month 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Revenge of the Nerds 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Pablo Montero Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.