Texas Statewide Historic Preservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

SUBCOMMITTEE on ARTICLES VI, VII, & VIII AGENDA MONDAY, MAY 2, 2016 10:00 A.M. ROOM E1.030 I. II. Charge #17: Review Histori

TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE ON ARTICLES VI, VII, & VIII LARRY GONZALES, CHAIR AGENDA MONDAY, MAY 2, 2016 10:00 A.M. ROOM E1.030 I. CALL TO ORDER II. CHAIRMAN’S OPENING REMARKS III. INVITED TESTIMONY Charge #17: Review historic funding levels and methods of financing for the state parks system. Study recent legislative enactments including the General Appropriations Act(84R), HB 158 (84R), and SB 1366 (84R) to determine the effect of the significant increase in funding, specifically capital program funding, on parks across the state. LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD • Michael Wales, Analyst • Mark Wiles, Manager, Natural Resources & Judiciary Team TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT • Carter Smith, Executive Director • Brent Leisure, State Park Division Director • Jessica Davisson, Infrastructure Division Director IV. PUBLIC TESTIMONY V. FINAL COMMENTS VI. ADJOURNMENT Overview of State Park System Funding PRESENTED TO HOUSE APPROPRIATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE ON ARTICLES VI, VIII, AND VIII LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD STAFF MAY 2016 Overview of State Park System Funding The Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) state parks system consists of 95 State Historic Sites, State Natural Areas, and State Parks, of which 91 are open to the public. State park-related appropriations fund operating the sites, the maintenance and capital improvements of state park infrastructure, associated administrative functions, providing grants to local parks and other entities for recreation opportunities, and advertising and publications related to the parks system. ● Total state parks-related appropriations for the 2016-17 biennium totals $375.9 million in All Funds, an increase of $83.6 million, or 28.6 percent , above the 2014-15 actual funding level. -

Senator Bettencourt Files SB 28 in the Texas Senate to Create Educational Opportunities for Texas Families

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 11, 2021 Contact: Cristie Strake (512) 463-0107 [email protected] Brian Whitley (510) 495-5542 [email protected] Senator Bettencourt Files SB 28 in the Texas Senate to Create Educational Opportunities for Texas Families Public Education Chair Harold Dutton filed identical companion, HB 3279 in Texas House The Charter School Equity Act will help more Texas students access public schools that meet their needs AUSTIN – Senator Paul Bettencourt (R-Houston) and Chairman Harold Dutton (D-Houston) file The Charter School Equity Act, which levels the playing field for successful public charter schools that are prepared to meet the needs of more Texas families. This bipartisan legislation has 11 joint-authors in the Texas Senate including Senators Birdwell, Buckingham, Campbell, Creighton, Hall, Hughes, Lucio, Paxton, Perry, Springer, and Taylor. Representative Harold Dutton (D-Houston) filed the companion bill, HB 3279, in the House. “Parents deserve to be in the driver’s seat when it comes to the education of their children,” said Senator Bettencourt. “This legislation ensures that public charter schools, which have a remarkably successful track record, can continue to give families access to schools that work for them.” he added. "Public charter schools are meeting the needs of families across Texas," said Representative Harold Dutton. "I'm pleased to work with Senator Bettencourt and my colleagues in the House on this important legislation that will give more students the opportunity to thrive." SB 28 puts parents and students first by preventing local governments from forcing charter schools to follow different rules than ISDs regarding zoning, permitting, and construction. -

Texas Education Agency Overview

Texas Education Agency Overview 100 - Office of the Commissioner; Senior Policy Advisor The Commissioner's Office provides leadership to schools, manages the Texas Education Agency (TEA), and provides coordination with the state legislature and other branches of state government as well as the U. S. Department of Education. SBOE activities and rules, commissioner rules and regulations, commissioner hearing decisions, coordinates with state legislature, Commissioner’s Correspondence and Complaints Management. Number of FTEs: 6 Correspondence Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to correspondence received by members of the public, local education agencies (LEAs), legislature, and other state agencies. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 03-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function serves as a review and distribution center for correspondence assigned to other offices in coordination with Complaints Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. Complaints Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to complaints received by members of the public. Through various activities, this function ensures that the operations of the Agency’s complaint system is compliant with applicable regulations and policy and effectively meets identified needs of the Agency. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 04-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function mainly serves as a review and distribution center for complaints assigned to other offices in coordination with Correspondence Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. -

Dr. J. W. Edgar Opinion No. (Ci379

Dr. J. W. Edgar Opinion No. (Ci379) Commissioner of Education Texas Education Agency Re: Whether The Classroom Austin, Texas Teachers of Dallas, a non-profit corporation, is exempt from payment of franchise taxes under Dear Dr. Edgar: stated facts. We quote In Its entirety your letter requesting the opinion of this office on the above captioned question. "The Classroom Teachers of Dallas is incorporated as a non-profit membership organization under the laws of Texas for the following purpose as stated in its charter: 'The purpose for which The Classroom Teachers of Dallas is formed is strictly educational, to-wit: The advancement of public school education in Texas.' ItI am informed that the organization, in pursuit of the stated purpose, engage8 in the following activities: "1 . It publishes and distributes The Dallas Teacher, a periodical including columns designed to provide beneficial information and significant news to the teaching profession. “2 . It distributes to the teachers educational pamphlets and materials printed by the National Education Association and the Texas State Teachers Association. "3. It organizes and assists in organizing Future Teachers of America Clubs in each high school and junior high school and participates extensively in the programs which are designed to provide information to future teachers. -1799- Dr. J.~W. Edgar, Page 2 Opinion No. (C- 379) “4 . It helps organize-. Student. .Education . .Associ- ations in colleges, supplies tnem witn eaucatlon materials and works with them in their programs which look toward teaching as a profession. “5 . It supplies speakers at local, district and state meetings of both Future Teachers of America and Student Education Associations. -

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas Texans Outdoors: An Analysis of 1985 Participation in Outdoor Recreation Activities By Kathryn N. Nichols and Andrew P. Goldbloom Under the Direction of James A. Deloney November, 1989 Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, Texas 78744 (512) 389-4900 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Conducting a mail survey requires accuracy and timeliness in every single task. Each individualized survey had to be accounted for, both going out and coming back. Each mailing had to meet a strict deadline. The authors are indebted to all the people who worked on this project. The staff of the Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division, deserve special thanks. This dedicated crew signed letters, mailed, remailed, coded, and entered the data of a twenty-page questionnaire that was sent to over twenty-five thousand Texans with over twelve thousand returned completed. Many other Parks Division staff outside the branch volunteered to assist with stuffing and labeling thousands of envelopes as deadlines drew near. We thank the staff of the Information Services Section for their cooperation in providing individualized letters and labels for survey mailings. We also appreciate the dedication of the staff in the mailroom for processing up wards of seventy-five thousand pieces of mail. Lastly, we thank the staff in the print shop for their courteous assistance in reproducing the various documents. Although the above are gratefully acknowledged, they are absolved from any responsibility for any errors or omissions that may have occurred. ii TEXANS OUTDOORS: AN ANALYSIS OF 1985 PARTICIPATION IN OUTDOOR RECREATION ACTIVITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................... -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District ANDERSON 396 - XXX D PALESTINE PICNIC AND CAMPING PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $136,086.77 C 8/23/1976 3/1/1979 2 719 - XXX D COMMUNITY FOREST PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $275,500.00 C 8/23/1979 8/31/1985 2 ANDERSON County Total: $411,586.77 County Count: 2 ANDREWS 931 - XXX D ANDREWS MUNICIPAL POOL CITY OF ANDREWS $237,711.00 C 12/6/1984 12/1/1989 19 ANDREWS County Total: $237,711.00 County Count: 1 ANGELINA 19 - XXX C DIBOLL CITY PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $174,500.00 C 10/7/1967 10/1/1971 2 215 - XXX A COUSINS LAND PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $113,406.73 C 8/4/1972 6/1/1973 2 297 - XXX D LUFKIN PARKS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $49,945.00 C 11/29/1973 1/1/1977 2 512 - XXX D MORRIS FRANK PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $236,249.00 C 5/20/1977 1/1/1980 2 669 - XXX D OLD ORCHARD PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $235,066.00 C 12/5/1978 12/15/1983 2 770 - XXX D LUFKIN TENNIS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $51,211.42 C 6/30/1980 6/1/1985 2 879 - XXX D HUNTINGTON CITY PARK CITY OF HUNTINGTON $35,313.56 C 9/26/1983 9/1/1988 2 ANGELINA County Total: $895,691.71 County Count: 7 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 2 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. -

A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 87 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-2012 Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley James Blackshear Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Blackshear, James. "Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley." New Mexico Historical Review 87, 3 (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol87/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Boots on the Ground a history of fort bascom in the canadian river valley James Blackshear n 1863 the Union Army in New Mexico Territory, prompted by fears of a Isecond Rebel invasion from Texas and its desire to check incursions by southern Plains Indians, built Fort Bascom on the south bank of the Canadian River. The U.S. Army placed the fort about eleven miles north of present-day Tucumcari, New Mexico, a day’s ride from the western edge of the Llano Estacado (see map 1). Fort Bascom operated as a permanent post from 1863 to 1870. From late 1870 through most of 1874, it functioned as an extension of Fort Union, and served as a base of operations for patrols in New Mexico and expeditions into Texas. Fort Bascom has garnered little scholarly interest despite its historical signifi cance. -

Archaeological Studies at the CPS Butler Lignite Prospect, Bastrop and Lee Counties, Texas, 1983

Volume 1986 Article 5 1986 Archaeological Studies at the CPS Butler Lignite Prospect, Bastrop and Lee Counties, Texas, 1983 Kenneth M. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Brown, Kenneth M. (1986) "Archaeological Studies at the CPS Butler Lignite Prospect, Bastrop and Lee Counties, Texas, 1983," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 1986, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.1986.1.5 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1986/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Studies at the CPS Butler Lignite Prospect, Bastrop and Lee Counties, Texas, 1983 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1986/iss1/5 Arehaeologieal Studies at the" CPSBIJTLER Lignite Prospeet., Bastrop and Lee Counties., Texas., 1983 Kenneth M. -

William Chapman 1642

Descendants of William Chapman Generation 1 1. WILLIAM1 CHAPMAN was born in 1652 in Ipswich, Essex County, Massschuetts. He died in 1732 in Amesbury, Windham County, Connecticut. He married ELISABETH SMITH. She was born in 1657 in Ipswich, Essex County, Massachuetts. She died in 1732 in Windham, Connecticut. Notes for William Chapman: This William, born in 1642 in Ipswich, Essex County, Massschuettes, is the earliest Chapman about which my data gathering has been able to include. He was born the year Maryland was founded by English colonists sent by the second Lord Baltimore. Source:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maryland "Chapman is English: occupational name for a merchant or trader, Middle English 'chapman,' Old English, 'ceapmann,' a compound of 'ceap' or 'barter,' or 'bargain,' 'price,' 'property The name was brought independently to North America from England by numerous different bearers from the 17th Century onward. John Chapman (sic)was one of the free planters who assented to the 'FundamentalAgreement' of the New Haven Colony on June 4, 169." Source: Patrick Hanks, Editor, Dictionary of American Family Names,Oxford University Press, New York, New York, 2003, Card #929.40973D554 2003 V.1, Dallas Public Library, Genealogical Section, page 318. William was born the year the first Oberammergau Passion Play was done, 1642. He lived until 1732, when he died and is presumed interred at Amesbury, Windham County, Connecticut. Source:http://www.oberammergau.de/ot_e/passionplay/ There is one character of fame in the Chapman line to whom it would be desirable to document relationship. However, tracking down the actual connection has eluded me. -

Texas Forts Trail Region

CatchCatch thethe PioPionneereer SpiritSpirit estern military posts composed of wood and While millions of buffalo still roamed the Great stone structures were grouped around an Plains in the 1870s, underpinning the Plains Indian open parade ground. Buildings typically way of life, the systematic slaughter of the animals had included separate officer and enlisted troop decimated the vast southern herd in Texas by the time housing, a hospital and morgue, a bakery and the first railroads arrived in the 1880s. Buffalo bones sutler’s store (provisions), horse stables and still littered the area and railroads proved a boon to storehouses. Troops used these remote outposts to the bone trade with eastern markets for use in the launch, and recuperate from, periodic patrols across production of buttons, meal and calcium phosphate. the immense Southern Plains. The Army had other motivations. It encouraged Settlements often sprang up near forts for safety the kill-off as a way to drive Plains Indians onto and Army contract work. Many were dangerous places reservations. Comanches, Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches with desperate characters. responded with raids on settlements, wagon trains and troop movements, sometimes kidnapping individuals and stealing horses and supplies. Soldiers stationed at frontier forts launched a relentless military campaign, the Red River War of 1874–75, which eventually forced Experience the region’s dramatic the state’s last free Native Americans onto reservations in present-day Oklahoma. past through historic sites, museums and courthouses — as well as historic downtowns offering unique shopping, dining and entertainment. ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ 2 The westward push of settlements also relocated During World War II, the vast land proved perfect cattle drives bound for railheads in Kansas and beyond. -

Domain Code Report Code with Description

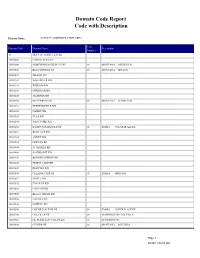

Domain Code Report Code with Description Element Name: AGENCY ADMINISTRATIVE AREA Line Domain Code Domain Name Description Number 10 DEPT OF AGRICULTURE 10000000 FOREST SERVICE 10010000 NORTHERN REGION USFS 01 MONTANA MISSOULA 10010200 BEAVERHEAD NF 01 MONTANA DILLON 10010201 DILLON RD 10010202 WISE RIVER RD 10010203 WISDOM RD 10010206 SHERIDAN RD 10010207 MADISON RD 10010300 BITTERROOT NF 01 MONTANA HAMILTON 10010301 STEVENSVILLE RD 10010302 DARBY RD 10010303 SULA RD 10010304 WEST FORK RD 10010400 IDAHO PANHANDLE NF 01 IDAHO COEUR D ALENE 10010401 WALLACE RD 10010402 AVERY RD 10010403 FERNAN RD 10010404 ST MARIES RD 10010406 SANDPOINT RD 10010407 BONNERS FERRY RD 10010408 PRIEST LAKE RD 10010409 RED IVES RD 10010500 CLEARWATER NF 01 IDAHO OROFINO 10010501 PIERCE RD 10010502 PALOUSE RD 10010503 CANYON RD 10010504 KELLY CREEK RD 10010505 LOCHSA RD 10010506 POWELL RD 10010600 COEUR D ALENE NF 01 IDAHO COEUR D ALENE 10010700 COLVILLE NF 01 WASHINGTON COLVILLE 10010710 NE WASH LUP (COLVILLE) 01 WASHINGTON 10010800 CUSTER NF 01 MONTANA BILLINGS Page 1 09/20/11 02:07 PM Line Domain Code Domain Name Description Number 10010801 SHEYENNE RD 10010802 BEARTOOTH RD 10010803 SIOUX RD 10010804 ASHLANDFORT HOWES RD 10010806 GRAND RIVER RD 10010807 MEDORA RD 10010808 MCKENZIE RD 10010810 CEDAR RIVER NG 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010820 DAKOTA PRAIRIES GRASSLAND 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010830 SHEYENNE NG 01 NORTH DAKOTA 10010840 GRAND RIVER NG 01 SOUTH DAKOTA 10010900 DEERLODGE NF 01 MONTANA BUTTE 10010901 DEER LODGE RD 10010902 JEFFERSON RD 10010903 PHILIPSBURG RD 10010904 BUTTE RD 10010929 DILLON RD 01 MONTANA DILLON 11 LANDS IN BUTTE RD, DEERLODGE NF ADMIN 12 ISTERED BY THE DILLON RD, BEAVERHEAD NF.