Near-Inertial Waves in Strongly Baroclinic Currents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symmetric Instability in the Gulf Stream

Symmetric instability in the Gulf Stream a, b c d Leif N. Thomas ⇤, John R. Taylor ,Ra↵aeleFerrari, Terrence M. Joyce aDepartment of Environmental Earth System Science,Stanford University bDepartment of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge cEarth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology dDepartment of Physical Oceanography, Woods Hole Institution of Oceanography Abstract Analyses of wintertime surveys of the Gulf Stream (GS) conducted as part of the CLIvar MOde water Dynamic Experiment (CLIMODE) reveal that water with negative potential vorticity (PV) is commonly found within the surface boundary layer (SBL) of the current. The lowest values of PV are found within the North Wall of the GS on the isopycnal layer occupied by Eighteen Degree Water, suggesting that processes within the GS may con- tribute to the formation of this low-PV water mass. In spite of large heat loss, the generation of negative PV was primarily attributable to cross-front advection of dense water over light by Ekman flow driven by winds with a down-front component. Beneath a critical depth, the SBL was stably strat- ified yet the PV remained negative due to the strong baroclinicity of the current, suggesting that the flow was symmetrically unstable. A large eddy simulation configured with forcing and flow parameters based on the obser- vations confirms that the observed structure of the SBL is consistent with the dynamics of symmetric instability (SI) forced by wind and surface cooling. The simulation shows that both strong turbulence and vertical gradients in density, momentum, and tracers coexist in the SBL of symmetrically unstable fronts. -

Ocean and Climate

Ocean currents II Wind-water interaction and drag forces Ekman transport, circular and geostrophic flow General ocean flow pattern Wind-Water surface interaction Water motion at the surface of the ocean (mixed layer) is driven by wind effects. Friction causes drag effects on the water, transferring momentum from the atmospheric winds to the ocean surface water. The drag force Wind generates vertical and horizontal motion in the water, triggering convective motion, causing turbulent mixing down to about 100m depth, which defines the isothermal mixed layer. The drag force FD on the water depends on wind velocity v: 2 FD CD Aa v CD drag coefficient dimensionless factor for wind water interaction CD 0.002, A cross sectional area depending on surface roughness, and particularly the emergence of waves! Katsushika Hokusai: The Great Wave off Kanagawa The Beaufort Scale is an empirical measure describing wind speed based on the observed sea conditions (1 knot = 0.514 m/s = 1.85 km/h)! For land and city people Bft 6 Bft 7 Bft 8 Bft 9 Bft 10 Bft 11 Bft 12 m Conversion from scale to wind velocity: v 0.836 B3/ 2 s A strong breeze of B=6 corresponds to wind speed of v=39 to 49 km/h at which long waves begin to form and white foam crests become frequent. The drag force can be calculated to: kg km m F C A v2 1200 v 45 12.5 C 0.001 D D a a m3 h s D 2 kg 2 m 2 FD 0.0011200 Am 12.5 187.5 A N or FD A 187.5 N m m3 s For a strong gale (B=12), v=35 m/s, the drag stress on the water will be: 2 kg m 2 FD / A 0.00251200 35 3675 N m m3 s kg m 1200 v 35 C 0.0025 a m3 s D Ekman transport The frictional drag force of wind with velocity v or wind stress x generating a water velocity u, is balanced by the Coriolis force, but drag decreases with depth z. -

Chapter 7 Balanced Flow

Chapter 7 Balanced flow In Chapter 6 we derived the equations that govern the evolution of the at- mosphere and ocean, setting our discussion on a sound theoretical footing. However, these equations describe myriad phenomena, many of which are not central to our discussion of the large-scale circulation of the atmosphere and ocean. In this chapter, therefore, we focus on a subset of possible motions known as ‘balanced flows’ which are relevant to the general circulation. We have already seen that large-scale flow in the atmosphere and ocean is hydrostatically balanced in the vertical in the sense that gravitational and pressure gradient forces balance one another, rather than inducing accelera- tions. It turns out that the atmosphere and ocean are also close to balance in the horizontal, in the sense that Coriolis forces are balanced by horizon- tal pressure gradients in what is known as ‘geostrophic motion’ – from the Greek: ‘geo’ for ‘earth’, ‘strophe’ for ‘turning’. In this Chapter we describe how the rather peculiar and counter-intuitive properties of the geostrophic motion of a homogeneous fluid are encapsulated in the ‘Taylor-Proudman theorem’ which expresses in mathematical form the ‘stiffness’ imparted to a fluid by rotation. This stiffness property will be repeatedly applied in later chapters to come to some understanding of the large-scale circulation of the atmosphere and ocean. We go on to discuss how the Taylor-Proudman theo- rem is modified in a fluid in which the density is not homogeneous but varies from place to place, deriving the ‘thermal wind equation’. Finally we dis- cuss so-called ‘ageostrophic flow’ motion, which is not in geostrophic balance but is modified by friction in regions where the atmosphere and ocean rubs against solid boundaries or at the atmosphere-ocean interface. -

Geostrophic Current Component Perpendicular to the Line Connecting a Station Pair - (Indirectly Measuring Current)

ATOC 5051 INTRODUCTION TO PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY Lecture 5 Learning objectives: (1)Know the modern ocean observing system that integrates in situ observations and remote sensing from space (satellite) (2) What is indirect method, why is it necessary, and how does it work? 1. Integrated observing system; 2. Indirect current measurement and application 1. Integrated observing system http://www.pmel.noaa.gov The Pacific TRITON (Triangle Trans-Ocean Buoy Network) TRITON array: east Indian & west Pacific (Japan) TAO Buoy and ship TAO/TRITON buoy data Moored buoy. Example: TAO/TRITON Moored buoy; Tropical Atmosphere Ocean (TAO); TRIangle Trans-Ocean buoy TRITON buoy Network (TRITON). https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/drupal/ani/ ATLAS (Autonomous Temperature Line Acquisition System) Data: https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/dru pal/ani/ The Research Moored Array for African-Asian-Australian Monsoon Analysis and Prediction (RAMA) initiated in ~2004; until march 2019: 90% complete 2011: CINDY/ DYNAMO In-situ: Calibrate Satellite data Piracy Current & future planned IndOOS maps Prioritized actionable recommendations: for next decade (46-33) Prediction and Research Moored Array in the Atlantic (PIRATA) Argo floats T,S PROFILE & CURRENTS AT INTERMEDIATE DEPTH http://www.argo.ucsd.edu/ Pop-up floats: ~10-days pop up, transmit data to ARGO satellite (~6hours up/down); on the way, collect T and S profile (0~2000m); (Surface: 6~12hours) currents at ~1000m (float drift-parking depth; then dive down to 2000m for T&S Profiling). Life cycles; ~150 repeated cycles. ARGO Floats (each 20-30kg) Argo floats T,S PROFILE & CURRENTS AT INTERMEDIATE DEPTH Float distribution as on August 30, 2019 • Gliders (mount sensors, e.g., ADCP); • Propel themselves by changing buoyancy; • Measure current, T, S, dissolved O2, etc.) from deeper ocean to surface; Good for measuring coastal ocean circulation. -

Structure and Transport of the North Atlantic Current in the Eastern

Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Structure and Transport of the North Atlantic Current 10.1029/2018JC014162 in the Eastern Subpolar Gyre From Sustained Key Points: Glider Observations • Two branches of the North Atlantic Current (named the Hatton Bank Jet 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 and the Rockall Bank Jet) are revealed L. Houpert , M. E. Inall , E. Dumont , S. Gary , C. Johnson , M. Porter , W. E. Johns , by repeated glider sections and S. A. Cunningham1 • Around 6.3+/-2.1 Sv is carried by the Hatton Bank Jet in summer, 1Scottish Association for Marine Science, Oban, UK, 2Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, Miami, FL, USA about 40% of the upper-ocean transport by the North Atlantic Current across 59.5N • Thirty percent of the Hatton Bank Abstract Repeat glider sections obtained during 2014–2016, as part of the Overturning in the Subpolar Jet transport is due to the vertical North Atlantic Program, are used to quantify the circulation and transport of North Atlantic Current (NAC) geostrophic shear while the branches over the Rockall Plateau. Using 16 glider sections collected along 58∘N and between 21∘W Hatton-Rockall Basin currents are ∘ mostly barotropic and 15 W, absolute geostrophic velocities are calculated, and subsequently the horizontal and vertical structure of the transport are characterized. The annual mean northward transport (± standard deviation) Correspondence to: is 5.1 ± 3.2 Sv over the Rockall Plateau. During summer (May to October), the mean northward transport is L. Houpert, stronger and reaches 6.7 ± 2.6 Sv. This accounts for 43% of the total NAC transport of upper-ocean waters [email protected] < . -

Lecture 4: OCEANS (Outline)

LectureLecture 44 :: OCEANSOCEANS (Outline)(Outline) Basic Structures and Dynamics Ekman transport Geostrophic currents Surface Ocean Circulation Subtropicl gyre Boundary current Deep Ocean Circulation Thermohaline conveyor belt ESS200A Prof. Jin -Yi Yu BasicBasic OceanOcean StructuresStructures Warm up by sunlight! Upper Ocean (~100 m) Shallow, warm upper layer where light is abundant and where most marine life can be found. Deep Ocean Cold, dark, deep ocean where plenty supplies of nutrients and carbon exist. ESS200A No sunlight! Prof. Jin -Yi Yu BasicBasic OceanOcean CurrentCurrent SystemsSystems Upper Ocean surface circulation Deep Ocean deep ocean circulation ESS200A (from “Is The Temperature Rising?”) Prof. Jin -Yi Yu TheThe StateState ofof OceansOceans Temperature warm on the upper ocean, cold in the deeper ocean. Salinity variations determined by evaporation, precipitation, sea-ice formation and melt, and river runoff. Density small in the upper ocean, large in the deeper ocean. ESS200A Prof. Jin -Yi Yu PotentialPotential TemperatureTemperature Potential temperature is very close to temperature in the ocean. The average temperature of the world ocean is about 3.6°C. ESS200A (from Global Physical Climatology ) Prof. Jin -Yi Yu SalinitySalinity E < P Sea-ice formation and melting E > P Salinity is the mass of dissolved salts in a kilogram of seawater. Unit: ‰ (part per thousand; per mil). The average salinity of the world ocean is 34.7‰. Four major factors that affect salinity: evaporation, precipitation, inflow of river water, and sea-ice formation and melting. (from Global Physical Climatology ) ESS200A Prof. Jin -Yi Yu Low density due to absorption of solar energy near the surface. DensityDensity Seawater is almost incompressible, so the density of seawater is always very close to 1000 kg/m 3. -

Ch.1: Basics of Shallow Water Fluid ∂

AOS611Chapter1,2/16/16,Z.Liu 1 Ch.1: Basics of Shallow Water Fluid Sec. 1.1: Basic Equations 1. Shallow Water Equations on a Sphere We start with the shallow water fluid of a homogeneous density and focus on the effect of rotation on the motion of the water. Rotation is, perhaps, the most important factor that distinguishes geophysical fluid dynamics from classical fluid dynamics. There are four basic equations involved in a homogeneous fluid system. The first is the mass equation: 1 d u 0 (1.1.1) dt 3 3 where 3 i x j y k z , u3 (u,v, w) . The other three equations are the momentum equations, which, in its 3-dimensional vector form can be written as: du 1 3 2Ù u p g F dt 3 3 (1.1.2) d where u dt t 3 3 On the earth, it is more convenient to cast the equations on the spherical coordinate with ,,r being the longitude, latitude and radians, respectively. That is: Copyright 2013, Zhengyu Liu AOS611Chapter1,2/16/16,Z.Liu 2 1 d 1 u 1 (vcos) w 0 dt rcos r cos r du u 1 p (2 )(v sin wcos ) F dt rcos r cos (1.1.3) dv u wv 1 p (2 )usin F dt rcos r r 2 dw u v 1 p (2 )u cos g Fr dt r cos r r This is a complex set of equations that govern the fluid motion from ripples, turbulence to planetary waves. For the atmosphere and ocean, many approximations can be made. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Phytoplankton in Surface Ocean Fronts : Resolving Biological Dynamics and Spatial Structure Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/61r5x33r Author De Verneil, Alain Joseph Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Phytoplankton in Surface Ocean Fronts: Resolving Biological Dynamics and Spatial Structure A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Oceanography by Alain Joseph de Verneil Committee in charge: Professor Peter J.S. Franks, Chair Professor Jorge Cortés Professor Michael R. Landry Professor Mark D. Ohman Professor Daniel L. Rudnick 2015 Copyright Alain Joseph de Verneil, 2015 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Alain Joseph de Verneil is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2015 iii DEDICATION To my family, Mama, Papa and Mary-Pat, Christine and Matt, Mamy and Papy, Paul Dano, and Claude duVerlie iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .................................................................................................................iii Dedication........................................................................................................................ iv Tables of Contents ........................................................................................................... -

Estimation of Geostrophic Current in the Red Sea Based on Sea Level Anomalies Derived from Extended Satellite Altimetry Data

Ocean Sci., 15, 477–488, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-477-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Estimation of geostrophic current in the Red Sea based on sea level anomalies derived from extended satellite altimetry data Ahmed Mohammed Taqi1,2, Abdullah Mohammed Al-Subhi1, Mohammed Ali Alsaafani1, and Cheriyeri Poyil Abdulla1 1Department of Marine Physics, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2Department of Marine Physics, Hodeihah University, Hodeihah, Yemen Correspondence: Ahmed Mohammed Taqi ([email protected]) Received: 8 April 2018 – Discussion started: 24 August 2018 Revised: 18 March 2019 – Accepted: 29 March 2019 – Published: 8 May 2019 Abstract. Geostrophic current data near the coast of the Red 1 Introduction Sea have large gaps. Hence, the sea level anomaly (SLA) data from Jason-2 have been reprocessed and extended to- The Red Sea is a narrow semi-enclosed water body that wards the coast of the Red Sea and merged with AVISO lies between the continents of Asia and Africa. It is lo- ◦ ◦ data at the offshore region. This processing has been ap- cated between 12.5–30 N and 32–44 E in a NW–SE ori- plied to build a gridded dataset to achieve the best results entation. Its average width is 220 km and the average depth for the SLA and geostrophic current. The results obtained is 524 m (Patzert, 1974). It is connected at its northern end from the new extended data at the coast are more con- with the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal and at sistent with the observed data (conductivity–temperature– its southern end with the Indian Ocean through the strait depth, CTD) and hence geostrophic current calculation. -

Do Eddies Play a Role in the Momentum Balance of the Leeuwin Current?

964 JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 35 Do Eddies Play a Role in the Momentum Balance of the Leeuwin Current? MING FENG CSIRO Marine Research, Floreat, Western Australia, Australia SUSAN WIJFFELS,STUART GODFREY, AND GARY MEYERS CSIRO Marine Research, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia (Manuscript received 2 March 2004, in final form 19 October 2004) ABSTRACT The Leeuwin Current is a poleward-flowing eastern boundary current off the western Australian coast, and alongshore momentum balance in the current has been hypothesized to comprise a southward pressure gradient force balanced by northward wind and bottom stresses. This alongshore momentum balance is revisited using a high-resolution upper-ocean climatology to determine the alongshore pressure gradient and altimeter and mooring observations to derive an eddy-induced Reynolds stress. Results show that north of the Abrolhos Islands (situated near the shelf break between 28.2° and 29.3°S), the alongshore momentum balance is between the pressure gradient and wind stress. South of the Abrolhos Islands, the Leeuwin Current is highly unstable and strong eddy kinetic energy is observed offshore of the current axis. The alongshore momentum balance on the offshore side of the current reveals an increased alongshore pressure gradient, weakened alongshore wind stress, and a significant Reynolds stress exerted by mesoscale eddies. The eddy Reynolds stress has a Ϫ0.5 Sv (Sv ϵ 106 m3 sϪ1) correction to the Indonesian Throughflow transport estimate from Godfrey’s island rule. The mesoscale eddies draw energy from the mean current through mixed barotropic and baroclinic instability, and the pressure gradient work overcomes the negative wind work to supply energy for the instability process. -

Observations of Surface Currents and Tidal Variability Off of Northeastern Taiwan from Shore-Based High Frequency Radar

remote sensing Article Observations of Surface Currents and Tidal Variability Off of Northeastern Taiwan from Shore-Based High Frequency Radar Yu-Ru Chen 1 , Jeffrey D. Paduan 2 , Michael S. Cook 2, Laurence Zsu-Hsin Chuang 1 and Yu-Jen Chung 3,* 1 Institute of Ocean Technology and Marine Affairs, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan; [email protected] (Y.-R.C.); [email protected] (L.Z.-H.C.) 2 Department of Oceanography, Naval Postgraduate School—NPS, Monterey, CA 93943, USA; [email protected] (J.D.P.); [email protected] (M.S.C.) 3 Department of Marine Science, Naval Academy, Kaohsiung 813, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A network of high-frequency radars (HFRs) has been deployed around Taiwan. The wide-area data coverage is dedicated to revealing near real-time sea-surface current information. This paper investigates three primary objectives: (1) describing the seasonal current synoptic variability; (2) determining the influence of wind forcing; (3) describing the tidal current field pattern and variability. Sea surface currents derived from HFR data include both geostrophic components and wind-driven components. This study explored vector complex correlations between the HFR time series and wind, which was sufficient to identify high-frequency components, including an Ekman balance among the surface currents and wind. Regarding the characteristics of mesoscale events and the tidal field, a year-long high-resolution surface dataset was utilized to observe the current–eddy– tide interactions over four seasons. The harmonic analysis results derived from surface currents off Citation: Chen, Y.-R.; Paduan, J.D.; Cook, M.S.; Chuang, L.Z.-H.; Chung, of northeastern Taiwan during 2013 are presented. -

A Coriolis Tutorial, Part 4

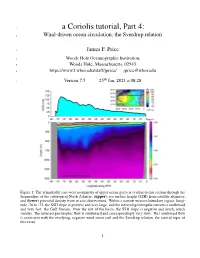

1 a Coriolis tutorial, Part 4: 2 Wind-driven ocean circulation; the Sverdrup relation 3 James F. Price 4 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 5 Woods Hole, Massachusetts, 02543 6 https://www2.whoi.edu/staff/jprice/ [email protected] th 7 Version7.5 25 Jan, 2021 at 08:28 Figure 1: The remarkable east-west asymmetry of upper ocean gyres is evident in this section through the thermocline of the subtropical North Atlantic: (upper), sea surface height (SSH) from satellite altimetry, and (lower) potential density from in situ observations. Within a narrow western boundary region, longi- tude -76 to -72, the SSH slope is positive and very large, and the inferred geostrophic current is northward and very fast: the Gulf Stream. Over the rest of the basin, the SSH slope is negative and much, much smaller. The inferred geostrophic flow is southward and correspondingly very slow. This southward flow is consistent with the overlying, negative wind stress curl and the Sverdrup relation, the central topic of this essay. 1 8 Abstract. This essay is the fourth of a four part introduction to Earth’s rotation and the fluid dynamics 9 of the atmosphere and ocean. The theme is wind-driven ocean circulation, and the motive is to develop 10 insight for several major features of the observed ocean circulation, viz. western intensification of upper 11 ocean gyres and the geography of the mean and the seasonal variability. 12 A key element of this insight is an understanding of the Sverdrup relation between wind stress curl 13 and meridional transport. To that end, shallow water models are solved for the circulation of a model 14 ocean that is started from rest and driven by a specified wind stress field: westerlies at mid-latitudes and 15 easterlies in subpolar and tropical regions.