Road Map of Symbols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

Cane River, Louisiana

''ewe 'Know <Who <We !A.re'' An Ethnographic Ove1'View of the Creole Traditions & Community of Isle Brevelle & Cane River, Louisiana H.F. Gregory, Ph.D. Joseph Moran, M.A. I /'I "1\ 1'We Know Who We Are": I An Ethnographic Overview of the Creole Community and Traditions of I Isle Breve lie and Cane River, Louisiana I I I' I I 'I By H.F. Gregory, Ph.D. I Joseph Moran, M.A. I I I Respectfully Submitted to: Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior I In partial fulfillment of Subagreement #001 to Cooperative Agreement #7029~4-0013 I I December, 1 996 '·1 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I Errata Page i - I "Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve" should read, "Jean Lafitte National I Historical Park and Preserve ...." Please define "emic" as the point of view from the culture as opposed to the I anthropological, descriptive view of the culture - the outsider's point ofview(etic). I Page vi- "Dr. Allison Pena" should read, "Ms. Allison Pena. ." I Page 13 - I "The first was literary-folkloristic which resulted in local color novels and romantic history - all but 'outside' authors and artists ... "should read, "The first was literary-folkloristic which I resulted in local color and romantic history - all by 'outside' authors and artists ...." I Page 14 - "Whenever Creoles tried to explain who they were, who they felt they were, it ultimately was, and is, interpreted as an attempt to passer pour blanc" should read, "Whenever Creoles tried I to explain who they were, who they felt they were, it ultimately was, and is, interpreted as an I attempt to passer pour blanc, or to pass for white... -

Understanding South Louisiana Through Literature

UNDERSTANDING SOUTH LOUISIANA THROUGH LITERATURE: FOLKTALES AND POETRY AS REPRESENTATIONS OF CULTURAL IDENTITY by ANNA BURNS (Under the direction of Dr. Nina Hellerstein) ABSTRACT Folktales represent particular cultural attitudes based on location, time period, and external and internal influences. Cultural identity traits appear through the storytellers, who emphasize these traits to continue cultural traditions. The folktales and poetry studied in this thesis show how various themes work together to form the Cajun and Creole cultures. The themes of occupation, music and dance, and values; religion, myth, and folk beliefs; history, violence, and language problems are examined separately to show aspects of Cajun and Creole cultures. Secondary sources provide cultural information to illustrate the attitudes depicted in the folktales and poetry. INDEX WORDS: Folktales, Poetry, Occupation, Religion, Violence, Cajun and Creole, Cultural Identity UNDERSTANDING SOUTH LOUISIANA THROUGH LITERATURE: FOLKTALES AND POETRY AS REPRESENTATIONS OF CULTURAL IDENTITY by ANNA BURNS B.A., Loyola University of New Orleans, 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2002 ©2002 Anna Burns All Rights Reserved UNDERSTANDING SOUTH LOUISIANA THROUGH LITERATURE: FOLKTALES AND POETRY AS REPRESENTATIONS OF CULTURAL IDENTITY by ANNA BURNS Major Professor: Dr. Nina Hellerstein Committee: Dr. Doris Kadish Dr. Tim Raser Electronic Version Approved: Gordhan L. Patel Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2002 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to all those who have supported me in various ways through this journey and many others. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all those who have given me superior guidance and support during my studies, particulary Dr. -

Guide to Gwens Databases

THE LOUISIANA SLAVE DATABASE AND THE LOUISIANA FREE DATABASE: 1719-1820 1 By Gwendolyn Midlo Hall This is a description of and user's guide to these databases. Their usefulness in historical interpretation will be demonstrated in several forthcoming publications by the author including several articles in preparation and in press and in her book, The African Diaspora in the Americas: Regions, Ethnicities, and Cultures (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming 2000). These databases were created almost entirely from original, manuscript documents located in courthouses and historical archives throughout the State of Louisiana. The project lasted 15 years but was funded for only five of these years. Some records were entered from original manuscript documents housed in archives in France, in Spain, and in Cuba and at the University of Texas in Austin as well. Some were entered from published books and journals. Some of the Atlantic slave trade records were entered from the Harvard Dubois Center Atlantic Slave Trade Dataset. Information for a few records was supplied from unpublished research of other scholars. 2 Each record represents an individual slave who was described in these documents. Slaves were listed, and descriptions of them were recorded in documents in greater or lesser detail when an estate of a deceased person who owned at least one slave was inventoried, when slaves were bought and sold, when they were listed in a will or in a marriage contract, when they were mortgaged or seized for debt or because of the criminal activities of the master, when a runaway slave was reported missing, or when slaves, mainly recaptured runaways, testified in court. -

African Reflections on the American Landscape

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Center for Cultural Resources African Reflections on the American Landscape IDENTIFYING AND INTERPRETING AFRICANISMS Cover: Moving clockwise starting at the top left, the illustrations in the cover collage include: a photo of Caroline Atwater sweeping her yard in Orange County, NC; an orthographic drawing of the African Baptist Society Church in Nantucket, MA; the creole quarters at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation in Thibodaux, LA; an outline of Africa from the African Diaspora Map; shotgun houses at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation; details from the African Diaspora Map; a drawing of the creole quarters at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation; a photo of a banjo and an African fiddle. Cover art courtesy of Ann Stephens, Cox and Associates, Inc. Credits for the illustrations are listed in the publication. This publication was produced under a cooperative agreement between the National Park Service and the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers. African Reflections on the American Landscape IDENTIFYING AND INTERPRETING AFRICANISMS Brian D. Joyner Office of Diversity and Special Projects National Center for Cultural Resources National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2003 Ta b le of Contents Executive Summary....................................................iv Acknowledgments .....................................................vi Chapter 1 Africa in America: An Introduction...........................1 What are Africanisms? ......................................2 -

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

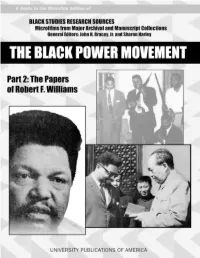

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

Visitlakecharles 800-456-SWLA LAKE CHARLES | SULPHUR | WESTLAKE DEQUINCY | VINTON | IOWA Welcome Y’All! What's Inside?

VisitLakeCharles.org #VisitLakeCharles 800-456-SWLA LAKE CHARLES | SULPHUR | WESTLAKE DEQUINCY | VINTON | IOWA Welcome Y’all! What's Inside? Share Your Story ...........................................................4 Casino Time ...................................................................6 Lake Charles/Southwest Louisiana Arts & Culture ...............................................................8 - The Gateway to Cajun Country Galleries & Museums Performing Arts Adventure and exploration await with a diverse offering Cultural Districts of culture, music, world-famous food, festivals, the great Where to Eat? .............................................................. 12 outdoors, casino gaming, top name entertainment and Dining Options historic attractions. So, unwind & have fun! Southwest Louisiana Boudin Trail Stop by the convention & visitors bureau, 1205 N. Fun Food Facts Lakeshore Drive, while you are in town. Visit with our Culinary Experiences friendly staff, have a cup of coffee and get tips on how to Cuisine & Recipes make your stay as memorable as possible. Creole vs. Cajun ...........................................................23 Music Scene .................................................................24 Connect with us & share your adventures! Looking for Live Music? facebook.com/lakecharlescvb Nightlife www.visitlakecharles.org/blog #visitlakecharles Adventure Tourism ......................................................27 Get Your Adventure On! Creole Nature Trail Adventure Point ...........................28 -

The Music of Louisiana: Cajuns, Creoles and Zydeco

The Music of Louisiana: Cajuns, Creoles and Zydeco Carole Poindexter-Sylvers INTRODUCTION The music and cuisine of southern Louisiana experienced a renaissance during the 1980s. Zydeco musicians and recording artists made appearances on morning talk shows, Cajun and Creole restaurants began to spring up across the nation, and celebrity chefs such Paul Prudhomme served as a catalyst for the surge in interest. What was once unknown by the majority of Americans and marginalized within the non-French speaking community in Louisiana had now become a national trend. The Acadians, originally from Acadia, Nova Scotia, were expelled from Canada and gradually became known as Cajuns. These Acadians or Cajuns proudly began teaching the lingua franca in their francophone communities as Cajun French, published children‘s books in Cajun French and school curricula in Cajun French. Courses were offered at local universities in Cajun studies and Cajun professors published scholarly works about Cajuns. Essentially, the once marginalized peasants had become legitimized. Cajuns as a people, as a culture, and as a discipline were deemed worthy of academic study stimulating even more interest. The Creoles of color (referring to light-skinned, French-speaking Negroid people born in Louisiana or the French West Indies), on the other hand, were not acknowledged to the same degree as the Cajuns for their autonomy. It would probably be safe to assume that many people outside of the state of Louisiana do not know that there is a difference between Cajuns and Creoles – that they are a homogeneous ethnic or cultural group. Creoles of color and Louisiana Afro-Francophones have been lumped together with African American culture and folkways or southern folk culture. -

The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture From

The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti by Christina Frances Mobley Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Bruce Hall ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Lisa Lindsay ___________________________ James Sweet Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 i v ABSTRACT The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti by Christina Frances Mobley Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Bruce Hall ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Lisa Lindsay ___________________________ James Sweet An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Christina Frances Mobley 2015 Abstract In my dissertation, “The Kongolese Atlantic: Central African Slavery & Culture from Mayombe to Haiti,” I investigate the cultural history of West Central African slavery at the height of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the late eighteenth century. My research focuses on the Loango Coast, a region that has received -

The New Orleans Free People of Color and the Process of Americanization, 1803-1896

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2005 The New Orleans Free People of Color and the Process of Americanization, 1803-1896 Camille Kempf Gourdet College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Gourdet, Camille Kempf, "The New Orleans Free People of Color and the Process of Americanization, 1803-1896" (2005). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626484. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-wf20-pk69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW ORLEANS FREE PEOPLE OF COLOR AND THE PROCESS OF AMERICANIZATION, 1803-1896 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Camille K. Gourdet 2005 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Camille Kempf feourdet Approved by the Committee, May 2005 sor, Chair kii HhtC'QuL. $you2, Kathleen Bragdon, Professor UX-— M. Lynn Weiss, Professor ii To my husband Nico, who has always stood firmly by my side. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Chapter I. -

2020-2021 Louisiana Cultural Equity Arts Grant Recipients

2020-2021 Louisiana Cultural Equity Arts Grant Recipients Kumbuka`=40 Years of Remembering Ausettua AmorAmenkum Kouri-Vini Chasidy Morris Anthony Bean Community Theater and Anthony Bean Communty Theater Acting School and Acting School 100 Years - The RISE and FALL of Voices in the Dark Repertory BLACK WALL STREET ( Saluting BLACK Theatre Company Producer/Director BUSINESSES in NOLA) -Tommy Myrick A Cultural Renaissance R & R: The Lula Elzy New Orleans Dance Regenerate and Reunion - the 30th Theatre Anniversary Celebration of the Lula Elzy New Orleans Dance Theatre Gordeax: Explorations of Southern Antonio Garza Louisiana Foodways Lamentations Chakra Dance Theatre We Must Save Our Schools Bianca Siplin Big Chief Brian and the Nouveau Brian Nelson Bounce presents Hell Out The Way Black Film Festival of New Orleans Black Film Festival/Gian Smith Follow Me! India McDougle Deep South by Suroeste "DSXSO" Charitable Film Network Angles Miles Labat The Congo Square Website Freddi Evans African American Female The New Quorum Musician/Composer/Writer Residency New Venture Theatre Presents "Kings" New Venture Theatre February 25 through March 7, 2021 Rhythm and Blues Rontherin Ratliff We are the Light: LUNA Fete 2020 Arts Council New Orleans COMING TOGETHER: A tribute to Ellis Jamar Pierre Marsalis & 2020 (Mural) Folk Art Zone Sculpture Garden Charles Gillam Portal: A Solo Exhibition of Art by Demond Melancon Demond Melancon at the Arthur Roger Gallery CONGO SQUARE LIVING CLASSROOM Congo Square Preservation Society FIELD-TRIP GLBL WRMNG Nate Cameron Jr. Ana Hernandez Ana Hernandez Pass It On open mic Ayo Scott Watercolors Interdisciplinary Jarrell Hamilton Performance Work Place Congo: Restoration of the Spirit Kai Knight CARL LEBLANC: NEW ORLEANS’ 7th Geovane Santos WARD MODERN JAZZ GRIOT Big Chief, Black Hawk Jonathan Isaac Jackson "Creole Music - a Musical Gumbo" Joseph Hall The Bartholomew House: Rising Artists- Journey LaToya Ondiyahla Allen in-Residence Community Black Masking Indian Tribal Roll Call Laurie A. -

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions by Ned Hémard

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard The Creole Virtues … and Vices Much has been brought up, grown up or arisen in New Orleans, the metropolis known as the Crescent City. The word crescent itself is derived from the Latin crescere, a form of the verb meaning “to grow, to become visible, to spring from, to come forth, to increase, to thrive or to augment.” This came to apply to the “increasing” form of the waxing moon (luna crescens). In English, the word is now commonly used to refer to either the moon’s waxing, or waning, shape. From there, it was only a matter of time before it would be used to describe other things with that shape, such as croissants or bends in the river, as in the case of New Orleans. But the crescent symbol was in use long before that, appearing on Akkadian seals as early as 2300 BC. That’s Akkadian, not Acadian, chèr. A crescent sail on the Mississippi, March 30, 1861, Harper’s Weekly: “one can perceive the peculiar conformation from which New Orleans derives its popular appellation of ‘The Crescent City.’” The word Créole has “brought up” quite a bit of controversy in its “upbringing”. Confusion continues to exist as to its meaning with regard to race or European heritage. The French word créole, from the Spanish criollo, meaning a person native to a locality, comes from the Portuguese crioulo, the diminutive of cria, a person raised in the house, especially a servant, from criar, to bring up, ultimately from the Latin verb creare, meaning to create or beget.