Socio-Cultural Processes and Livelihood Patterns at Tirurangadi- a Micro Historical Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malappuram District from 18.10.2020To24.10.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Malappuram district from 18.10.2020to24.10.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 DARAB, BURUPADA, ABDUL GAJAPATI, 21-10- JFCM 1, 22, MALAPPURA 606/2020 MALAPPUR LATHEEF, SI 1 DASNAIK KASLNAIK ODISHA, NOW AT 2020 AT MALAPPUR MALE M PS U/s 380 IPC AM MALAPPURA MELMURI 11:30 HRS AM M MALAPPURAM KERALA INDIA SANGEETH.P, CHOLASSERY H 18-10- 599/2020 18, MALAPPUR SI BAILED BY 2 SHAHEER SIDEEQUE VADEKKEMANNA KOTTAPADY 2020 AT U/s 27(b) of MALE AM MALAPPURA POLICE KODOOR PO 18:30 HRS NDPS Act M 336/2020 ATTAKULAYAN U/s 57 of KP 22-10- MUHAMMED JFCM 1, ALAVIKKUT 32, (H), Act altered in 3 MAJIDA VENGARA PS 2020 AT VENGARA RAFEEQUE, MALAPPUR TY MALE THARAYITTAL, to 317 IPC & 13:38 HRS SI VENGARA AM VENGARA Sec 75 of JJ Act KALIPPADAN HOUSE, 23-10- 640/2020 23, ALIPPARAMBU, MANCHERR JAISON, SI JFCM 1, 4 YOUSAF MOIDEEN MANJERI 2020 AT U/s 225(b) MALE KUNNANATH PO, Y MANJERI MANJERI 20:20 HRS IPC PERINTHALMANN A, MPM 523/2020 VALIYAKAVIL U/s 509 IPC ADDL. RADHA 20-10- AMED ,SUB 45, HOUSE,IRUVETTY & Sec 12 r/w AREAKKOD SESSIONS 5 KRISHNAN. RAMAN ELAYOOR 2020 AT INSPECTOR MALE POST, 11(1) of E COURT I, V.K 16:13 HRS OF POLICE MADARUKUNDU POCSO ACT MANJERI 2012 VADAKKEVEETIL 384/2020 20-10- SUBISH MOHAMME ABDURAHM 34, HOUSE EDAVANNAP U/s 279 IPC , VAZHAKKA BAILED BY 6 2020 AT MON, -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Annual Report 2016-17

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 Shaping the Nation ANSAL PROPERTIES & INFRASTRUCTURE LIMITED CIN : L45101DL1967PLC004759 Annual Report 2016-17 1 CIN : L45101DL1967PLC004759 Annual Report 2016-17 CONTENTS Page No. Company Information 3 Notice of Annual General Meeting 4-14 Location of Annual General Meeting 15 Directors’ Report 16-50 Corporate Governance Report 51-78 Management Discussion & Analysis 79-90 Auditors’ Report 91-97 Balance Sheet 98 Statement of Profit & Loss Account 99 Cash Flow Statement 100-101 Notes 103-159 Consolidated Accounts 160-233 Financial details of Subsidiary & Joint Venture Companies 234-236 for the year ended 31st March, 2017 as per Section 129 of Companies Act, 2013 and its Rules. Attendance Slip 237 Proxy Form 239 2 CIN : L45101DL1967PLC004759 Annual Report 2016-17 COMPANY INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Shri Sushil Ansal Chairman & Whole Time Director Shri Pranav Ansal Vice Chairman & Whole Time Director Shri Anil Kumar Joint Managing Director & Chief Executive Officer Shri D. N. Davar Independent Director Dr. R. C. Vaish Independent Director Dr. Prem Singh Rana Independent Director Dr. Lalit Bhasin Independent Director Shri P. R. Khanna Independent Director Smt. Archana Capoor Independent Director AUDIT COMMITTEE MEMBERS NOMINATION AND REMUNERATION COMMITTEE MEMBERS Shri D. N. Davar Chairman Shri D. N. Davar Chairman Dr. R. C. Vaish Vice Chairman Dr. R. C. Vaish Member Shri P. R. Khanna Member Dr. Prem Singh Rana Member Dr. Prem Singh Rana Member Dr. Lalit Bhasin Member Shri P. R. Khanna Member VICE PRESIDENT (FINANCE & ACCOUNTS) & CFO Shri Sunil Kumar Gupta COMPANY SECRETARY Shri Abdul Sami STATUTORY AUDITORS M/s. S. S. Kothari Mehta & Co. -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

In the High Court of Kerala at Ernakulam Present The

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM PRESENT THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE RAJA VIJAYARAGHAVAN V WEDNESDAY, THE 28TH DAY OF APRIL 2021 / 8TH VAISAKHA, 1943 WP(C).No.33596 OF 2019(Y) PETITIONERS: 1 THE KODUR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.R.1523, VALIYAD, KODUR P.O., MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 676 504, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY K.MOHANADASAN. 2 PULAMANTHOLE SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.F 1565, PULAMANTHOLE P.O., MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 323, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY ABOOBACKER. 3 THE ELAMKULAM SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.F.1536, KUNNAKKAVU P.O., MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 340, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY T.ARUNKUMAR. 4 THE PUNNAPPALA SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.F.928, P.O.NADUVATH, VIA WANDOOR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 328, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY SATHIANATHAN K.P. 5 THE PORUR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.357, P.O.CHATHANGOTTUPURAM, WANDOOR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 328, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY RAGHUNATH E. 6 THE CHOKKAD SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.602, P.O.CHOKKAD, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 352, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY SAJEEVAN NAIR V.P. 7 THE WANDOOR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.387, P.O.WANDOOR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 328, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY UMMER A.P. 8 THE TRIPRANGODE SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.1890, P.O.TRIPANGODE, TIRUR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 676 108, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY P.V.SURESH. 9 THE NIRAMARUTHUR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.612, KUMARANPADI P.O., PIN - 676 109, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY CHANDRAN V.K. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Malappuram District from 21.02.2021To27.02.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Malappuram district from 21.02.2021to27.02.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THATTAMBALATH MUHAMMED HOUSE, 24-02- JFCM ABDURAHM 28, 55/2021 U/s MALAPPUR ALI, SI 1 SHAJAHAN KORAPPADAM, KOZHIKODE 2021 AT MALAPPUR AN MALE 454, 380 IPC AM MALAPPURA MUNDUMUZHI, 14:00 HRS AM M VAZHAKKAD(PO) UMMER PULIKKAL HOUSE, MUTTIPPALA 21-02-2021 76/2021 U/s MEMANA, MUHAMME 38, THIRUVEGAPPURA, MANCHERR JFCM-1 2 FIROS BABU M, AT 18:40 20(b)(ii)B of SUB D MALE KAIPPURAM, Y MANJERI ANAKKAYAM HRS NDPS Act INSPECTOR, KOPPAM MANJERI PS ANOOP P G, KORADAN HOUSE 21-02-2021 29, KOTTAKKAL 53/2021 U/s KOTTAKKA SI BAILED BY 3 MUNEER SIDHIQUE PARAMBILANGADI AT 20:45 MALE PS 279, 283 IPC L KOTTAKKAL POLICE KOTTAKKAL HRS PS 52/2021 U/s ANOOP P G, ELANKULAVAN 21-02-2021 ABDULKARE 27, KOTTAKKAL 279 IPC, 118 KOTTAKKA SI BAILED BY 4 JAFAR HOUSE AT 20:30 EM MALE PS (e) KP Act, L KOTTAKKAL POLICE PANDIKKAD HRS 185 MV Act PS 50/2021 U/s FIROSE KANNIYAN HO, 26-02- CHANDRAM JFCM-1 ABDURAHM 35, 20(b)(II)(B) , 5 RAHMAN @ SHAPPINKUNNU, KONDOTTY 2021 AT KONDOTTY OHAN, IP MALAPPUR AN MALE 29 of NDPS KOSI FIROS PULPATTA 09:30 HRS KONDOTTY AM Act KIZHAKKANTE 23-02- SUBRAN SI, JFCM-1 HUSSAIN 25, PURAKKAL HOUSE, KONDOTTY 91/2021 U/s 6 UMARALI 2021 AT KONDOTTY KONDOTTY MALAPPUR KOYA MALE ARIYALLOOR, PS 379, 34 -

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of Engg. Trivandrum Mohammed

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of engg. Trivandrum Mohammed Shajahan P COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ABDUL AZEEZ C Government Engineering College Thrissur ABDUL AZEEZ KT Federal Institute of Science and Technology Abdul Basith Government Engineering College, Wayanad Abdul Basith K GEC palakkad Abdul Mahroof N MEA Engineering college perinthalmanna ABDUL MAJID K T Gov. Engineering college kozhikode Abdul Muhsin v Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Malabar Polytechnic college, Kottakkal Abdul Vahid B. S MES COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING,KUTTIPPURAM ABDUL VARIS N FISAT Abhay Krishna SD Tkm college of engineering Abhijit k Nehru college of engineering and reasearch centre Abhijith uk MES CET, KUNNUKARA Abhimanyu ks TKM College Of Engineering, Kollam ABHIRAJ.P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING KOTTARAKKARA ABHIRAM P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING TRIVANDATUM ABHIRAM P jawaharlal college of engineering and technology Abhishek A S Sreepathy institute of Management and technology Abijith g GEC PALAKKAD ADARSH DAS N Lal Bahadur Shastri College of Engineering, ADARSH DAS.P Eranad Knowledge City Technical Campus Adhil Fuad M.E.S College Of Engineering Adhin Gopuj.A COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY VALANCHERI ADHINI ULLAS AK GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING COLLEGE THRISSUR ADITHYA KUMAR M S Al ameen engineering college Adnan mohamed ali College of Engineering Trivandrum Afnan Mohammed A Government engineering college idukki Aghil.P MESCE AHAMED SHAMZAD MK MEA Engineering College Perinthalmanna Ahammed Jouhar E T Mes engineering college kuttipuram Ahammed rasheek Government Engineering College Thrissur AHNAS P P Ncerc Ajay Anand C Govt. -

EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl

LIST OF HIGH SCHOOLS IN MALAPPURAM DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl. Std. Std. HS/HSS/VHSS Boys/G Name of Name of School Address with Pincode Block Taluk No. (Fro (To) /HSS & irls/ Panchayat/Muncip m) VHSS/TTI Mixed ality/Corporation GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS 1 Arimbra GVHSS Arimbra - 673638 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Morayur Malappuram Eranad 2 Edavanna GVHSS Edavanna - 676541 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Edavanna Wandoor Nilambur 3 Irumbuzhi GHSS Irumbuzhi - 676513 VIII XII HSS Mixed Anakkayam Malappuram Eranad 4 Kadungapuram GHSS Kadungapuram - 679321 I XII HSS Mixed Puzhakkattiri Mankada Perinthalmanna 5 Karakunnu GHSS Karakunnu - 676123 VIII XII HSS Mixed Thrikkalangode Wandoor Eranad 6 Kondotty GVHSS Melangadi, Kondotty - 676 338. V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Kondotty Kondotty Eranad 7 Kottakkal GRHSS Kottakkal - 676503 V XII HSS Mixed Kottakkal Malappuram Tirur 8 Kottappuram GHSS Andiyoorkunnu - 673637 V XII HSS Mixed Pulikkal Kondotty Eranad 9 Kuzhimanna GHSS Kuzhimanna - 673641 V XII HSS Mixed Kuzhimanna Areacode Eranad 10 Makkarapparamba GVHSS Makkaraparamba - 676507 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Makkaraparamba Mankada Perinthalmanna 11 Malappuram GBHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Boys Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 12 Malappuram GGHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Girls Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 13 Manjeri GBHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Mixed Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 14 Manjeri GGHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Girls Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 15 Mankada GVHSS Mankada - 679324 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Mankada Mankada -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

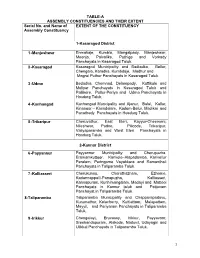

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kozhikode City District from 07.07.2019To13.07.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Kozhikode City district from 07.07.2019to13.07.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 CHATHANADPAR TRAFFIC IN FRONT 07-07-2019 634/2019 U/s NANDANA 23, AMBA(H), STATION BAILED BY 1 SANATH K OF INDOOR at 11:45 279 IPC & 185 SI JALEEL.T N Male THACHILOTTUPA (Kozhikode POLICE STADIUM Hrs MV ACT RAMBA, KALLAI City) Kathikamthottupara Christian NADAKKA 07-07-2019 618/2019 U/s 44, mb, Near Vellayil College Jn., VU Nandakumar, BAILED BY 2 Faisal. N.P. Usman at 13:50 279 IPC & 185 Male PS, West Hill Post, Kannur Road (Kozhikode SI of Police POLICE Hrs of MV Act Kozhikode Kozhikode City) 196/2019 U/s Baithul Shahida, CHEMMAN 07-07-2019 279 IPC& Muhammad Muhammad 32, Pallikandi, Chemmangad GADU BAILED BY 3 at 14:05 132(1) r/w SI Saneesh V Hashim Koya Male Kallai(po), PS (Kozhikode POLICE Hrs 179 of MV Kozhikode City) Act Padinjarayil- House, 07-07-2019 FEROKE Muhammed 18, 393/2019 U/s Subair. N, SI BAILED BY 4 Shoukathali Puthuppadam, Feroke PS at 14:20 (Kozhikode Adil. N Male 279, 338 IPC of Police POLICE Ayikkarappadi Hrs City) Krishna Nivas KUNNAMA 07-07-2019 491/2019 U/s Unnikrishna Govindan 45, Kannambathidam NGALAM BAILED BY 5 Karanthur at 16:10 118(a) of KP Sreejith SI n K Nair Male Melekathoth (Kozhikode POLICE Hrs Act Paingottupuram City) 594/2019 U/s Karadan House, -

Ground Water Information Booklet of Alappuzha District

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भजू ल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, मलꥍपुरम स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA जी श्रीनाथ सहायक भूजल ववज्ञ G. Sreenath Asst Hydrogeologist KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASAPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA TABLE OF CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2.0 CLIMATE AND RAINFALL ................................................................................... 3 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES .............................................................. 4 4.0 GROUNDWATER SCENARIO ............................................................................... 5 5.0 GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY .............................................. 11 6.0 GROUNDWATER RELATED ISaSUES AND PROBLEMS ............................... 14 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY ....................................................... 14