Reconsidering Jean Renoir's La Marseillaise Through Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partie De Campagne : Un Film « Inachevé » ? Partie De Campagne : an “Unfinished” Film?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenEdition 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 57 | 2009 Varia Partie de campagne : un film « inachevé » ? Partie de campagne : an “unfinished” film? Marie Robert Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/4013 DOI : 10.4000/1895.4013 ISBN : 978-2-8218-0988-8 ISSN : 1960-6176 Éditeur Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma (AFRHC) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 avril 2009 Pagination : 98-124 ISBN : 978-2-913758-58-2 ISSN : 0769-0959 Référence électronique Marie Robert, « Partie de campagne : un film « inachevé » ? », 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze [En ligne], 57 | 2009, mis en ligne le 01 avril 2012, consulté le 23 septembre 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/1895/4013 ; DOI : 10.4000/1895.4013 © AFRHC Eli Lotar, photo de tournage, Partie de campagne, coll. Cinémathèque française. Partie de campagne : un film « inachevé » ? par Marie Robert 1895 / Souvent considéré comme le chef-d’œuvre de Jean Renoir, Partie de campagne1, après avoir n° 57 avril connu des vicissitudes de tournage, resta inachevé à l’été 1936 et ne vit le jour en 1946 que 2009 par la volonté du producteur Pierre Braunberger, qui avait d’ailleurs été à l’origine de son interruption. Sur ce film, des sources écrites et archivistiques ont été interprétées dans des travaux relatifs, 99 entre autres, à Jean Renoir, à Jacques Prévert, à Jacques-Bernard Brunius et à Eli Lotar, mais pas jusqu’à présent dans l’optique du producteur, dont le rôle créateur fut pourtant déter- minant. -

The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens

dining in the sanctuary of demeter and kore 1 Hesperia The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens Volume 78 2009 This article is © The American School of Classical Studies at Athens and was originally published in Hesperia 78 (2009), pp. 269–305. This offprint is supplied for personal, non-commercial use only. The definitive electronic version of the article can be found at <http://dx.doi.org/10.2972/hesp.78.2.269>. hesperia Tracey Cullen, Editor Editorial Advisory Board Carla M. Antonaccio, Duke University Angelos Chaniotis, Oxford University Jack L. Davis, American School of Classical Studies at Athens A. A. Donohue, Bryn Mawr College Jan Driessen, Université Catholique de Louvain Marian H. Feldman, University of California, Berkeley Gloria Ferrari Pinney, Harvard University Sherry C. Fox, American School of Classical Studies at Athens Thomas W. Gallant, University of California, San Diego Sharon E. J. Gerstel, University of California, Los Angeles Guy M. Hedreen, Williams College Carol C. Mattusch, George Mason University Alexander Mazarakis Ainian, University of Thessaly at Volos Lisa C. Nevett, University of Michigan Josiah Ober, Stanford University John K. Papadopoulos, University of California, Los Angeles Jeremy B. Rutter, Dartmouth College A. J. S. Spawforth, Newcastle University Monika Trümper, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Hesperia is published quarterly by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Founded in 1932 to publish the work of the American School, the jour- nal now welcomes submissions from all scholars working in the fields of Greek archaeology, art, epigraphy, history, materials science, ethnography, and literature, from earliest prehistoric times onward. -

The Techniques of Realism and Fantasy for the Expression of the Political in French Cinema from Its Origins to the New Wave

THE EXPRESSION OF THE POLITICAL IN FRENCH CINEMA THE TECHNIQUES OF REALISM AND FANTASY FOR THE EXPRESSION OF THE POLITICAL IN FRENCH CINEMA FROM ITS ORIGINS TO THE NEW WAVE By FRANCES OKSANEN, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University October 1990 MASTER OF ARTS (1990) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (French) Hamilton~ Ontario TITLE: The Techniques of Realism and Fantasy for the Expression of the Political in French Cinema from its Origins to the New Wave AUTHOR: Frances Oksanen, B. A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor John Stout NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 167. ii .... '. ABSTRACT This study examines the relationship between film techniques and politics in French cinema. The first filmmakers established the basic techniques of cinema, using realism to record events, and fantasy to create amusements. Narrative film developed as a combination of these techniques. Cinema of the twenties was closely associated with the European art movements of Dadaism, Surrealism and Expressionism. By the thirties, the political polarisation and the threat of a second World War caused filmmakers to project political opinions and to portray societal problems. Narrative film became an important means of influencing public opinion, although not always in the directions intended. With the New Wave, autobiographical content and a return to early film techniques made narrative film both personal and traditional. The directors solidified the reputation of French cinema as topical, socially relevant, and politically involved. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor John C. Stout for his advice through the course of my research, and Professor Charles E. -

Partie De Campagne : Un Film « Inachevé » ? Partie De Campagne : an “Unfinished” Film?

1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 57 | 2009 Varia Partie de campagne : un film « inachevé » ? Partie de campagne : an “unfinished” film? Marie Robert Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/4013 DOI : 10.4000/1895.4013 ISBN : 978-2-8218-0988-8 ISSN : 1960-6176 Éditeur Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma (AFRHC) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 avril 2009 Pagination : 98-124 ISBN : 978-2-913758-58-2 ISSN : 0769-0959 Référence électronique Marie Robert, « Partie de campagne : un film « inachevé » ? », 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze [En ligne], 57 | 2009, mis en ligne le 01 avril 2012, consulté le 19 mars 2021. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/1895/4013 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/1895.4013 © AFRHC 1895 No57 16-3-2009 bis:Mise en page 1 16/04/09 11:31 Page 98 Eli Lotar, photo de tournage, Partie de campagne, coll. Cinémathèque française. 1895 No57 16-3-2009 bis:Mise en page 1 16/04/09 11:31 Page 99 Partie de campagne : un film « inachevé » ? par Marie Robert 1895 / Souvent considéré comme le chef-d’œuvre de Jean Renoir, Partie de campagne1, après avoir n° 57 avril connu des vicissitudes de tournage, resta inachevé à l’été 1936 et ne vit le jour en 1946 que 2009 par la volonté du producteur Pierre Braunberger, qui avait d’ailleurs été à l’origine de son interruption. Sur ce film, des sources écrites et archivistiques ont été interprétées dans des travaux relatifs, 99 entre autres, à Jean Renoir, à Jacques Prévert, à Jacques-Bernard Brunius et à Eli Lotar, mais pas jusqu’à présent dans l’optique du producteur, dont le rôle créateur fut pourtant déter- minant. -

Final Weeks of Popular Jean Renoir Retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1994 FINAL WEEKS OF POPULAR JEAN RENOIR RETROSPECTIVE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART The Museum of Modern Art's popular retrospective of the complete extant work of director Jean Renoir (1894-1979), one of cinema's great masters, continues through November 27, 1994. Presented in commemoration of the centenary of the director's birth, the exhibition comprises thirty-seven works, including thirty-three films by Renoir and a 1993 BBC documentary about the filmmaker by David Thompson. Twenty-three of the works by Renoir have been drawn from the Museum's film archives. Many of the remaining titles are also from the Cinematheque frangaise, Paris, and Interama, New York. The son of the Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Jean Renoir produced a rich and complex oeuvre that mined the spectacle of life, in all its fascinating inconstancy. In 1967 he said, "I'm trying to discover human beings, and sometimes I do." Although critics and scholars disagree on how to categorize Renoir's films -- some believe that his work can be divided into periods, while others argue that his films should be viewed as an indivisible whole -- there is no dissent about their integrity. His works are unfailingly humane, psychologically acute, and bursting with visual and aural moments that propel the narratives. - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 Highlights of the second half of the program include a new 35mm print of La Bete humaine (The Beast in Man, 1938), a powerful adaptation of a novel by Emile Zola, previously available in the United States only in 16mm. -

Legislative Assembly Approve Laws/Declarations of War Must Pay Considerable Taxes to Hold Office

Nat’l Assembly’s early reforms center on the Church (in accordance with Enlightenment philosophy) › Take over Church lands › Church officials & priests now elected & paid as state officials › WHY??? --- proceeds from sale of Church lands help pay off France’s debts This offends many peasants (ie, devout Catholics) 1789 – 1791 › Many nobles feel unsafe & free France › Louis panders his fate as monarch as National Assembly passes reforms…. begins to fear for his life June 1791 – Louis & family try to escape to Austrian Netherlands › They are caught and returned to France National Assembly does it…. after 2 years! Limited Constitutional Monarchy: › King can’t proclaim laws or block laws of Assembly New Constitution establishes a new government › Known as the Legislative Assembly Approve laws/declarations of war must pay considerable taxes to hold office. Must be male tax payer to vote. Problems persist: food, debt, etc. Old problems still exist: food shortages & gov’t debt Legislative Assembly can’t agree how to fix › Radicals (oppose monarchy & want sweeping changes in gov’t) sit on LEFT › Moderates (want limited changes) sit in MIDDLE › Conservatives (uphold limited monarchy & want few gov’t changes) sit on RIGHT Emigres (nobles who fled France) plot to undo the Revolution & restore Old Regime Some Parisian workers & shopkeepers push for GREATER changes. They are called Sans-Culottes – “Without knee britches” due to their wearing of trousers Monarchs & nobles across Europe fear the revolutionary ideas might spread to their countries Austria & Prussia urge France to restore Louis to power So the Legislative Assembly ………. [April 1792] Legislative Assembly declares war against Prussia and Austria › Initiates the French Revolutionary Wars French Revolutionary Wars: series of wars, from 1792-1802. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

GAUMONT PRESENTS: a CENTURY of FRENCH CINEMA, on View Through April 14, Includes Fifty Programs of Films Made from 1900 to the Present

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release January 1994 GAUNONT PRESENTS: A CENTURY OF FRENCH CINEMA January 28 - April 14, 1994 A retrospective tracing the history of French cinema through films produced by Gaumont, the world's oldest movie studio, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on January 28, 1994. GAUMONT PRESENTS: A CENTURY OF FRENCH CINEMA, on view through April 14, includes fifty programs of films made from 1900 to the present. All of the films are recently restored, and new 35mm prints were struck especially for the exhibition. Virtually all of the sound films feature new English subtitles as well. A selection of Gaumont newsreels [actualites) accompany the films made prior to 1942. The exhibition opens with the American premiere of Bertrand Blier's Un deux trois soleil (1993), starring Marcello Mastroianni and Anouk Grinberg, on Friday, January 28, at 7:30 p.m. A major discovery of the series is the work of Alice Guy-Blache, the film industry's first woman producer and director. She began making films as early as 1896, and in 1906 experimented with sound, using popular singers of the day. Her film Sur la Barricade (1906), about the Paris Commune, is featured in the series. Other important directors whose works are included in the exhibition are among Gaumont's earliest filmmakers: the pioneer animator and master of trick photography Emile Cohl; the surreal comic director Jean Durand; the inventive Louis Feuillade, who went on to make such classic serials as Les Vampires (1915) and Judex (1917), both of which are shown in their entirety; and Leonce Perret, an outstanding early realistic narrative filmmaker. -

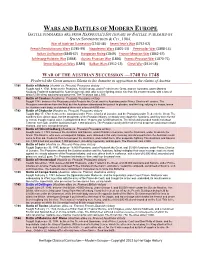

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

La Grande Illusion

La Grande Illusion 'Boeldieu?' bellows the German officer who is performing the roll call. 'De Boeldieu?' The only reply is the sound of a flute through the night air. The prisoner of war camp commandant, Von Rauffenstein, held tightly in a neck brace, nervously adjusts his monocle before taking it out again in order to better pinpoint the location of the missing French officer, who is casually sitting on top of the fortress walls. The white-gloved Captain De Boeldieu plays a tune, 'le petit navire' (the little boat) on his flute (which had remained undetected and therefore had been not confiscated by his jailers). A huge commotion breaks out in the main courtyard of the castle, known as Wintersborn in the film. The hunt for De Boeldieu is taken up by German soldiers and the beams of searchlights. He runs up the steps of the staircase, hardly touching the ground. Lieutenant Maréchal and Lieutenant Rosenthal make the most of the confusion and quietly steal away from their French, British and Russian fellow-prisoners. They have a length of rope that they made right under the noses of their guards. They throw the rope off the top of a wall and successfully escape from the forbidding medieval fortress that now serves as a prisoner of war camp. Meanwhile, De Boeldieu makes his way across a snow-covered roof to a mass of rocks. He taunts his pursuers with a tune on his flute. They take aim and fire, but the fugitive officer throws himself to the ground just in time. -

Timeline (PDF)

Timeline of the French Revolution 1789 1793 May 5 Estates General convened in Versailles Jan. 21 Execution of Louis XVI (and later, Marie Jun. 17 National Assembly Antoinette on Oct. 16) Jun. 20 Tennis Court Oath Feb. 1 France declares war on British and Dutch (and Jul. 11 Necker dismissed on Spain on Mar. 7) Jul. 13 Bourgeois militias in Paris Mar. 11 Counterrevolution starts in Vendée Jul. 14 Storming of the Bastille in Paris (official start of Apr. 6 Committee of Public Safety formed the French Revolution) Jun. 1-2 Mountain purges Girondins Jul. 16 Necker recalled Jul. 13 Marat assassinated Jul. 20 Great Fear begins in the countryside Jul. 27 Maximilien Robespierre joins CPS Aug. 4 Abolition of feudalism Aug. 10 Festival of Unity and Indivisibility Aug. 26 Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen Sept. 5 Terror the order of the day Oct. 5 Adoption of Revolutionary calendar 1791 1794 Jun. 20-21 Flight to Varennes Aug. 27 Declaration of Pillnitz Jun. 8 Festival of the Supreme Being Jul. 27 9 Thermidor: fall of Robespierre 1792 1795 Apr. 20 France declares war on Austria (and provokes Prussian declaration on Jun. 13) Apr. 5/Jul. 22 Treaties of Basel (Prussia and Spain resp.) Sept. 2-6 September massacres in Paris Oct. 5 Vendémiare uprising: “whiff of grapeshot” Sept. 20 Battle of Valmy Oct. 26 Directory established Sept. 21 Convention formally abolishes monarchy Sept. 22 Beginning of Year I (First Republic) 1797 Oct. 17 Treaty of Campoformio Nov. 21 Berlin Decree 1798 1807 Jul. 21 Battle of the Pyramids Aug. -

Dépliant Visite De Valmy (GB)

Visit of the site THE WINDMILL This present windmill is the fourth since 1792. The first one, which was not situated exactly on this spot, was destroyed on the day of the battle under Kellermann’s orders because it was a target point for the ennemy artillery. It was rebuilt with the reparation money, but at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was demolished, like all windmills in France because it had become of no use. In 1939, on the 150th anniversary of the battle, a windmill which had been bought in Flanders was re-erected but because of the 2nd world war, it was not inaugurated until the 20th of September 1947. During the bicentenary festival, a huge ferris wheel was set up. As it rotated, it symbolized the long forgotten movement of the slats. It had been designed so that it could rotate on its central axis in order to face the wind. But time passed and damages were caused and the windmill had to be placed upon a concrete base and has often been restaured. The windmill was destroyed by the storm on the 26th december 1999. A new windmill, built in the factory of Villeneuve d’Ascq (North of France), has been especially convoyed up to the site on the 1st of april 2005. It is now possible to see it mowing wheat and producing flour like in 1792. THE BATTLE FIELD Four orientation tables show the position of the troops. The center of the ennemy were positioned on the “ Côte de la Lune ” (200m.