How to Minimize the Pain of Local Anesthetic Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP

Information for Behavioral Health Providers in Primary Care Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP What are Hallucinogens? Hallucinogenic compounds found in some plants and mushrooms (or their extracts) have been used— mostly during religious rituals—for centuries. Almost all hallucinogens contain nitrogen and are classified as alkaloids. Many hallucinogens have chemical structures similar to those of natural neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine-, serotonin-, or catecholamine-like). While the exact mechanisms by which hallucinogens exert their effects remain unclear, research suggests that these drugs work, at least partially, by temporarily interfering with neurotransmitter action or by binding to their receptor sites. This InfoFacts will discuss four common types of hallucinogens: LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide) is one of the most potent mood-changing chemicals. It was discovered in 1938 and is manufactured from lysergic acid, which is found in ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains. Peyote is a small, spineless cactus in which the principal active ingredient is mescaline. This plant has been used by natives in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States as a part of religious ceremonies. Mescaline can also be produced through chemical synthesis. Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine) is obtained from certain types of mushrooms that are indigenous to tropical and subtropical regions of South America, Mexico, and the United States. These mushrooms typically contain less than 0.5 percent psilocybin plus trace amounts of psilocin, another hallucinogenic substance. PCP (phencyclidine) was developed in the 1950s as an intravenous anesthetic. Its use has since been discontinued due to serious adverse effects. How Are Hallucinogens Abused? The very same characteristics that led to the incorporation of hallucinogens into ritualistic or spiritual traditions have also led to their propagation as drugs of abuse. -

Local Anesthetic Half Life (In Hours) Lidocaine 1.6 Mepivacaine 1.9 Bupivacaine 353.5 Prilocaine 1.6 Articaine 0.5

Local Anesthetics • The first local anesthetics History were cocaine and procaine (Novacain) developed in ltlate 1800’s • They were called “esters” because of their chemical composition • Esters had a slow onset and short half life so they did not last long History • Derivatives of esters called “amides” were developed in the 1930’s • Amides had a faster onset and a longer half life so they lasted longer • AidAmides quiklickly repldlaced esters • In dentistry today, esters are only found in topical anesthetics Generic Local Anesthetics • There are five amide anesthetics used in dentistry today. Their generic names are; – lidocaine – mepivocaine – bupivacaine – prilocaine – artica ine • Each is known by at least one brand name Brand Names • lidocaine : Xylocaine, Lignospan, Alphacaine, Octocaine • mepivocaine: Carbocaine, Arestocaine, Isocaine, Polocaine, Scandonest • prilocaine : Citanest, Citanest Forte • bibupivaca ine: MiMarcaine • articaine: Septocaine, Zorcaine About Local Anesthetic (LA) • Local anesthetic (LA) works by binding with sodium channels in neurons preventing depolarization • LA is inactivated at the injection site when it is absorbed into the blood stream and redistributed throughout the body • If enough LA is absorbed, sodium channels in other parts of the body will be blocked, causing systemic side effects About LA • A clinical effect of LAs is dilation blood vessels, speeding up absorption and distribution • To counteract this dilation so anesthesia is prolonged, , a vasoconstrictor is often added to LAs • However, vasoconstrictors have side effects also Metabolism and Excretion • Most amide LAs are metabolized (inactivated) by the liver and excreted by the kidneys. • Prilocaine is partially metabolized by the lungs • Articaine is partially metabolized by enzymes in the bloo d as well as the liver. -

Monitoring Anesthetic Depth

ANESTHETIC MONITORING Lyon Lee DVM PhD DACVA MONITORING ANESTHETIC DEPTH • The central nervous system is progressively depressed under general anesthesia. • Different stages of anesthesia will accompany different physiological reflexes and responses (see table below, Guedel’s signs and stages). Table 1. Guedel’s (1937) Signs and Stages of Anesthesia based on ‘Ether’ anesthesia in cats. Stages Description 1 Inducement, excitement, pupils constricted, voluntary struggling Obtunded reflexes, pupil diameters start to dilate, still excited, 2 involuntary struggling 3 Planes There are three planes- light, medium, and deep More decreased reflexes, pupils constricted, brisk palpebral reflex, Light corneal reflex, absence of swallowing reflex, lacrimation still present, no involuntary muscle movement. Ideal plane for most invasive procedures, pupils dilated, loss of pain, Medium loss of palpebral reflex, corneal reflexes present. Respiratory depression, severe muscle relaxation, bradycardia, no Deep (early overdose) reflexes (palpebral, corneal), pupils dilated Very deep anesthesia. Respiration ceases, cardiovascular function 4 depresses and death ensues immediately. • Due to arrival of newer inhalation anesthetics and concurrent use of injectable anesthetics and neuromuscular blockers the above classic signs do not fit well in most circumstances. • Modern concept has two stages simply dividing it into ‘awake’ and ‘unconscious’. • One should recognize and familiarize the reflexes with different physiologic signs to avoid any untoward side effects and complications • The system must be continuously monitored, and not neglected in favor of other signs of anesthesia. • Take all the information into account, not just one sign of anesthetic depth. • A major problem faced by all anesthetists is to avoid both ‘too light’ anesthesia with the risk of sudden violent movement and the dangerous ‘too deep’ anesthesia stage. -

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens What Are Hallucinogens? Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that alter a person’s awareness of their surroundings as well as their thoughts and feelings. They are commonly split into two categories: classic hallucinogens (such as LSD) and dissociative drugs (such as PCP). Both types of hallucinogens can cause hallucinations, or sensations and images that seem real though they are not. Additionally, dissociative drugs can cause users to feel out of control or disconnected from their body and environment. Some hallucinogens are extracted from plants or mushrooms, and others are synthetic (human-made). Historically, people have used hallucinogens for religious or healing rituals. More recently, people report using these drugs for social or recreational purposes. Hallucinogens are a Types of Hallucinogens diverse group of drugs Classic Hallucinogens that alter perception, LSD (D-lysergic acid diethylamide) is one of the most powerful mind- thoughts, and feelings. altering chemicals. It is a clear or white odorless material made from lysergic acid, which is found in a fungus that grows on rye and other Hallucinogens are split grains. into two categories: Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) comes from certain classic hallucinogens and types of mushrooms found in tropical and subtropical regions of South dissociative drugs. America, Mexico, and the United States. Peyote (mescaline) is a small, spineless cactus with mescaline as its main People use hallucinogens ingredient. Peyote can also be synthetic. in a wide variety of ways DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is a powerful chemical found naturally in some Amazonian plants. People can also make DMT in a lab. -

Pharmacology – Inhalant Anesthetics

Pharmacology- Inhalant Anesthetics Lyon Lee DVM PhD DACVA Introduction • Maintenance of general anesthesia is primarily carried out using inhalation anesthetics, although intravenous anesthetics may be used for short procedures. • Inhalation anesthetics provide quicker changes of anesthetic depth than injectable anesthetics, and reversal of central nervous depression is more readily achieved, explaining for its popularity in prolonged anesthesia (less risk of overdosing, less accumulation and quicker recovery) (see table 1) Table 1. Comparison of inhalant and injectable anesthetics Inhalant Technique Injectable Technique Expensive Equipment Cheap (needles, syringes) Patent Airway and high O2 Not necessarily Better control of anesthetic depth Once given, suffer the consequences Ease of elimination (ventilation) Only through metabolism & Excretion Pollution No • Commonly administered inhalant anesthetics include volatile liquids such as isoflurane, halothane, sevoflurane and desflurane, and inorganic gas, nitrous oxide (N2O). Except N2O, these volatile anesthetics are chemically ‘halogenated hydrocarbons’ and all are closely related. • Physical characteristics of volatile anesthetics govern their clinical effects and practicality associated with their use. Table 2. Physical characteristics of some volatile anesthetic agents. (MAC is for man) Name partition coefficient. boiling point MAC % blood /gas oil/gas (deg=C) Nitrous oxide 0.47 1.4 -89 105 Cyclopropane 0.55 11.5 -34 9.2 Halothane 2.4 220 50.2 0.75 Methoxyflurane 11.0 950 104.7 0.2 Enflurane 1.9 98 56.5 1.68 Isoflurane 1.4 97 48.5 1.15 Sevoflurane 0.6 53 58.5 2.5 Desflurane 0.42 18.7 25 5.72 Diethyl ether 12 65 34.6 1.92 Chloroform 8 400 61.2 0.77 Trichloroethylene 9 714 86.7 0.23 • The volatile anesthetics are administered as vapors after their evaporization in devices known as vaporizers. -

Calcium-Channel Blockers and Anaesthesia

75 Review Article Calcium-channel blockers and Pierre-Georges Durand MD,* Jean-Jacques Lehot MD,* Pierre Fo~x D I)l'h~" anaesthesia Verapamil was the first calcium-channel blocker (CCB). It has Contents been used since 1962 in Europe then in Japan for its anti- Comparative pharmacology of calcium-channel blockers arrhythmic and coronary vasodilator effects/ The CCB have (CCB) become prominant cardiovascular drugs during the last 15 - Classification and chemical characteristics ),ears. Many experimental and clinical studies ha ve defined their - Mechanism of action mechanism of action, the effects of new drugs in this therapeutic - Pharmacokinetics class, and their indications and interactions with other drugs. - Interactions Due to the large number of patients treated with CCB it is - Pharmacodynamic effects important for the anaesthetist to know the general and specific Indications not related to anaesthesia problems involved during the perioperative period, the interac- - Confirmed indications tions with anaesthetics and the practical use of these drugs. - Possible indications Pharmacological interactions in anaesthesia Le verapamil a dtd initialement utilis6 comme un bloqueur des - Halogenated anaesthetics canaux calciques (CCB). 11 a ~t~ utilis6 depuis 1962 eta Europe - Other anaesthetics puis au Japon pour ses propri~tds anti-arythmiques et ses - Neuromuscular relaxants effets vaso-dilatateurs coronariens, i Les CCB sont devenus des Perioperative use drogues cardiovasculaires de choix depuis les 15 dernikres - Myocardial ischaemia -

Femoral Nerve Block Versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb

Alexandria Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44 Femoral Nerve Block versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb Peripheral Vascular Surgery By Ahmed Mansour, MD Assistant Professor of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University. Abstract Perioperative cardiac complications occur in 4% to 6% of patients undergoing infrainguinal revascularization under general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia. The risk may be even greater in patients whose cardiac disease cannot be fully evaluated or treated before urgent limb salvage operations. Prompted by these considerations, we investigated the feasibility and results of using femoral nerve block with infiltration of the genito4femoral nerve branches in these high-risk patients. Methods: Forty peripheral vascular reconstruction of lower limbs were performed under either spinal anesthesia (20 patients) or femoral nerve block with infiltration of genito-femoral nerve branches supplemented with local infiltration at the site of dissection as needed (20 patients). All patients had arterial lines. Arterial blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring was continued during surgery, in PACU and in the intensive care units. Results: Operations included femoral-femoral, femoral-popliteal bypass grafting and thrombectomy. The intra-operative events showed that the mean time needed to perform the block and dose of analgesics and sedatives needed during surgery was greater in group I (FNB,) compared to group II [P=0.01*, P0.029* , P0.039*], however, the time needed to start surgery was shorter in group I than in group II [P=0. 039]. There were no block failures in either group, but local infiltration in the area of the dissection with 2 ml (range 1-5 ml) of 1% lidocaine was required in 4 (20%) patients in FNB group vs none in the spinal group. -

Lidocaine Infusion for Analgesia MOA Pharmacology 1

Lidocaine Infusion for Analgesia MOA Pharmacology 1. Attenuation of proinflammatory effects: Ø Hepatic metabolism with high extraction ratio; Ø Blocks polymorphonuclear granulocyte priming, plasma clearance is 10 ml/kg/min13 reducing release of cytokines & reactive oxygen species1 Ø Adjust dose based on hepatic function and 2. Diminish nociceptive signaling to central nervous system: blood flow Ø Inhibition of G-protein-mediated effects2 Ø Renal clearance of metabolites Ø Reduces sensitivity & activity of spinal cord neurons Ø Context-sensitive half-time after a 3-day infusion is (glycine and NMDA receptor mediated)3,4 ∼20–40 min Ø Clinical effect of lidocaine tends to exceed the 5 3. Reduces ectopic activity of injured afferent nerves duration of the infusion by 5.5 times the half-life, supporting the putative preventive analgesia effect14 Perioperative Use Dosing Ø IV local anesthetic infusions have been used safely for pain control in the perioperative setting since the early 1950’s6,7 Infusion: 2mg/kg/hr (range 1.5-3 mg/kg/hr) Ø Reduce pain, nausea, ileus duration, opioid requirement, Loading dose: 1.5mg/kg (range 1-2 mg/kg) and length of hospital stay Ø Strongly consider bolus to rapidly achieve therapeutic concentration, otherwise steady state 9-12 Evidence for Specific Surgeries: reached in 4-8 hr Ø Strong: Open & laparoscopic abdominal; Reduces Max dose: 4.5 mg/kg postoperative pain, speeds return of bowel function, Ø Consider total dose from other local anesthetics reduces PONV, reduces length of hospital stay (e.g. regional anesthesia, periarticular injections, & Ø Moderate: Open prostatectomy, thoracic procedures, local infiltration) ambulatory surgery, and major spine; Reduces Continuous infusions up to 3 mg/kg/hr have been postoperative pain and opioid consumption shown to be safe Ø Moderate: Breast; Prevention of chronic postsurgical pain Ø Reduce infusion rate in patients with impaired Ø No benefit: Total abdominal hysterectomy, total hip drug metabolism & clearance (i.e. -

Local Anesthetic Toxicity: Prevention and Treatment

Local Anesthetic Toxicity: Prevention and Treatment John W. Wolfe, M.D. Staff Anesthesiologist Indiana University School of Medicine Indianapolis, Indiana John F. Butterworth, M.D. Chairman, Department of Anesthesia Indiana University School of Medicine Indianapolis, Indiana LESSON OBJECTIVES dine, and the site of injection on peak Upon completion of this lesson, the reader local anesthetic concentrations in blood. should be able to: 6. Describe the mechanism of local anes- 1. List the signs and symptoms of local thetic central nervous system toxicity. anesthetic toxicity. 7. Identify the risk factors for local anes- 2. Discuss the concept of "maximum safe thetic toxicity. doses of a local anesthetic." 8. Plan the treatment of local anesthetic- 3. Describe methods for reducing the risk of induced cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac local anesthetic toxicity. arrest. 4. Explain the treatment of local anes- 9. Describe the mechanism of local anes- thetic-related neurologic symptoms and thetic cardiovascular toxicity. toxic side effects. 10. Explain the dosage and proposed mech- 5. Discuss the effects of epinephrine, cloni- anism of lipid emulsion therapy. Current Reviews for Nurse Anesthetists designates this lesson for 1 CE contact hour in Clinical pharmacology/therapeutics. Introduction Mechanism of Cardiac and central nervous system (CNS) toxic Local Anesthetic Toxicity side effects of local anesthetics are relatively rare but potentially catastrophic complications of local and Local anesthetics normally produce their desired regional anesthesia. Fortunately, the likelihood of a effects on peripheral nerves by binding and inhibit- local anesthetic toxic event can be reduced by ad- ing voltage-gated sodium channels in neural cell herence to good technique. -

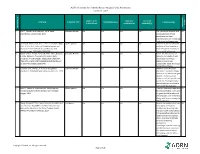

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table SAMPLE SIZE/ CONTROL/ OUTCOME CITATION EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTION(S) CONCLUSION(S) POPULATION COMPARISON MEASURE(S) SCORE CONSENSUS REFERENCE # REFERENCE 1 Lirk P., Picardi S. and Hollmann, M. W. Local Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a The mechanism of action and VA anaesthetics: 10 essentials. 2014 access pathways of local anesthetics and their pharmokinetics are increasingly understood and appreciated. 2 Calatayud, Jesús, M.D.,D.D.S., Ph.D., González, Õngel, Expert Opinion n/a n/a n/a n/a A review of the discovery and VA M.D., D.D.S., Ph.D. History of the development and evolution of local anesthesia evolution of local anesthesia since the coca leaf. from the Spanish discovery of Anesthesiology. 2003;98(6):1503-1508. the coca leaf in America. 3 Gordh T, M.D., Gordh, Torsten E.,M.D., Ph.D., Lindqvist Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Before the introduction of VA K, M.Sc. Lidocaine: The origin of a modern local lidocaine, the choice of local anesthetic. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1433-1437. anesthetics was limited. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. doi: Lidocaine's onset was 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. substantially faster and longer lasting than procaine. 4 Volcheck G.W., Mertes, P. M. Local and general Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Whether to test the local VA anesthetics immediate hypersensitivity reactions. 2014 anesthetic causing the allergic reaction or an alternative agent depends on the expected future need of the specific local anesthetic. -

The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures

Volume 2- Issue 1 : 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000695 Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Mini Review Open Access The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada MD* Received: January 17, 2018; Published: January 25, 2018 *Corresponding author: Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada, Ex-Professor of Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery, Teresópolis Schoolof Medicine, Rio de Janeiro, Rua Jose da Silva Ribeiro 119 apt 11 São Paulo, SP Brazil CEP: 05726-130, Email: Abstract The local anesthetics are widely u sed in minor pediatric surgical procedures. The major problem with their use is the resulted pain experienced by the patients at the time of injection. To discuss those situations in the light of the medical literature we present this mini-review. Key words: Local Injection; Pain; Buffer; pH; Lidocaine; Pediatric Surgery Procedure Introduction Table 1: Techniques for injection pain control*. a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) cream [17] S.No Techniques for injection pain control before infiltration, and local external cooling (cryoanalgesia) have 1. Warming the anesthetic solution [18,19] (Table 1). also been used to reduce the pain of infiltration of local anesthetic 2. Buffering the anesthetic Buffering the Anesthetic 3. Injection technique 4. Distraction Local anesthesia is extremely useful either as the sole method the best results on the minor surgery in general [3,6]. Blocking 5. Combination anesthetic technique the pain pathway with local anesthetic solution will also reduce 6. Cooling of skin the family stress response to the surgical procedure. -

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens What are hallucinogens? Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that alter a person’s awareness of their surroundings as well as their own thoughts and feelings. They are commonly split into two categories: classic hallucinogens (such as LSD) and dissociative drugs (such as PCP). Both types of hallucinogens can cause hallucinations, or sensations and images that seem real though they are not. Additionally, dissociative drugs can cause users to feel out of control or disconnected from their body and environment. Some hallucinogens are extracted from plants or mushrooms, and some are synthetic (human- made). Historically, people have used hallucinogens for religious or healing rituals. More recently, people report using these drugs for social or recreational purposes, including to have fun, deal with stress, have spiritual experiences, or just to feel different. Common classic hallucinogens include the following: • LSD (D-lysergic acid diethylamide) is one of the most powerful mind-altering chemicals. It is a clear or white odorless material made from lysergic acid, which is found in a fungus that grows on rye and other grains. LSD has many other street names, including acid, blotter acid, dots, and mellow yellow. • Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N- dimethyltryptamine) comes from certain types of mushrooms found in tropical and subtropical regions of South America, Mexico, and the United States. Some common names for Blotter sheet of LSD-soaked paper squares that users psilocybin include little smoke, magic put in their mouths. mushrooms, and shrooms. Photo by © DEA • Peyote (mescaline) is a small, spineless cactus with mescaline as its main ingredient. Peyote can also be synthetic.