June 2020 Editors: Fiona Fowler & Maya Donelan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Locations Britain in the 1930S and 40S

Key Locations Britain in the 1930s and 40s Marcus Garvey Park Hamlet Gardens 2 Beaumont Crescent Dieppe Street St. Dunstan’s Road 53 Talgarth Road Section 10 Marcus Garvey Curriculum Links Objectives This section can provide links Children should learn: with History Unit 20 ‘What can we learn about recent history • to identify Marcus Garvey and compile a historical narrative from studying the life of a famous person?’. It links to Citizenship • to examine the portrayal of Marcus Garvey by extracting by introducing the idea of information from reference material including support politics through a controversial material, accompanying DVD and internet sources figure from recent history. It also provides links to ICT Unit 2C • to select information to represent key aspects of a biography ‘Finding information’ and Unit 6D • to begin to evaluate the impact of Marcus Garvey on the ‘Using the internet’. history of his time and his legacy This section links to Key Stage 3 History Unit 15 ‘Black peoples Activities of America from slavery to equality?’ and Citizenship Unit 1. Using support and reference material, ask the children to write 03 ‘Human rights’. their own account of the life of Marcus Garvey, focusing on the political nature of his activities. 2. Ask the children to think about what being famous means. Why Outcomes is Marcus Garvey more famous in the Caribbean and USA than The children could: he is in Britain? Should he be more famous in Britain? • summarise the key events in Marcus Garvey’s life in a 3. Ask the children to discuss, in small groups, ways of chronological sequence representing Marcus Garvey’s life and achievements. -

Fulham Palace Visitor Leaflet and Site

Welcome to Fulham Palace Pick up our What’s On guide to House and Garden, the find out about upcoming events home of the Bishops of London since AD 704, and We would love /fulhampalacetrust to see your photos! @fulham_palace a longer history stretching @fulhampalace back 6,000 years. Our site includes our historic house Getting here and garden, museum and café; we invite you to explore. Open daily • Free entry Wheelchair and pushchair friendly All ages are welcome to explore our site Drawing Bishop Bishop room café Porteus’s Howley’s library room Bishop Terrick’s p rooms East court Access Ram Chapel Bishop Great hall Sherlock’s room Putney Bridge Putney Exit to Fulham Palace is located on Bishop’s Avenue, just West (Tudor) court o Fulham Palace Road (A219). Visit our website for further information on getting to Fulham Palace including coach access and street parking. West (Tudor) court Museum rooms Accessibility Public areas of Fulham Palace are accessible and Visitor assistance dogs are welcome. Limited accessible parking is available to book. Visit out website for further information. information Shop Fulham Palace Trust Bishop’s Avenue Fulham and site map Main entrance London, SW6 6EA +44 (0)20 7736 3233 Education centre [email protected] Open daily • Free admission * Some rooms may be closed from time Registered charity number 1140088 fulhampalace.org to time for private events and functions Home to a history that never stands still Market barrow Walled garden Buy fresh, organic produce Explore the knot garden, orchard grown in our garden. and bee hives. -

What Is Village Planning Guidance?

Kew Village INTRODUCTION TO VILLAGE PLANNING GUIDANCE FOR KEW What is Village Planning Guidance? How can I get involved? London Borough of Richmond upon Thames (LBRuT) wants residents and businesses to help prepare ‘Village Planning Guidance’ for the Kew Village area. There will be two different stages of engagement This will be a document that the Council considers when deciding on planning and consultation before the guidance is adopted. applications. Village Planning Guidance can: During November and December 2013 residents and • Help to identify, with your help, what the ‘local character’ of your area is and businesses are being asked about their vision for the what features need to be retained. future of their areas, thinking about: • Help protect and enhance the local character of your area, particularly if it is • the local character not a designated ‘conservation area’. • heritage assets • Establish key design principles that new development should respond to. • improvement opportunities for specific sites or areas • other planning policy or general village plan issues • The boundary has been based on the Village Plan area to reflect the views of where people live. The open parts of the Thames Policy Area (as Spring 2014 - draft guidance will be written after denoted in purple on the photograph below) will not form part of the Christmas based on your views and a formal (statutory) guidance as this is already covered by a range of other policies. consultation carried out in March/April 2014 before adoption. How does Village Planning Guidance work? How does the ‘Village Planning Guidance’ relate to Village Plans? The Village Planning Guidance will become a formal planning policy ‘Supplementary Planning Document’ (SPD) which the council will take The Planning Guidance builds on the ‘Village Plans’ which account of when deciding on planning applications, so it will influence were developed from the 2010 ‘All in One’ survey developers and householders in preparing plans and designs. -

The Great War, 1914-18 Biographies of the Fallen

IRISH CRICKET AND THE GREAT WAR, 1914-18 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE FALLEN BY PAT BRACKEN IN ASSOCIATION WITH 7 NOVEMBER 2018 Irish Cricket and the Great War 1914-1918 Biographies of The Fallen The Great War had a great impact on the cricket community of Ireland. From the early days of the war until almost a year to the day after Armistice Day, there were fatalities, all of whom had some cricket heritage, either in their youth or just prior to the outbreak of the war. Based on a review of the contemporary press, Great War histories, war memorials, cricket books, journals and websites there were 289 men who died during or shortly after the war or as a result of injuries received, and one, Frank Browning who died during the 1916 Easter Rising, though he was heavily involved in organising the Sporting Pals in Dublin. These men came from all walks of life, from communities all over Ireland, England, Scotland, Wales, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, India and Sri Lanka. For all but four of the fifty-two months which the war lasted, from August 1914 to November 1918, one or more men died who had a cricket connection in Ireland or abroad. The worst day in terms of losses from a cricketing perspective was the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, when eighteen men lost their lives. It is no coincidence to find that the next day which suffered the most losses, 9 September 1916, at the start of the Battle of Ginchy when six men died. -

108-114 FULHAM PALACE ROAD Hammersmith, London W6 9PL

CGI of Proposed Development 108-114 FULHAM PALACE ROAD Hammersmith, London W6 9PL West London Development Opportunity 108-114 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 9PL 2 INVESTMENT LOCATION & HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION • Residential led development The site is situated on the west side of Fulham opportunity in the London Borough Palace Road, at the junction of the Fulham Palace Road and Winslow Road, in the London of Hammersmith & Fulham. Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. • 0.09 hectare (0.21 acre). The surrounding area is characterised by a mix of uses; Fulham Palace Road is typified by 3 • Existing, mixed-use building storey buildings with retail at ground floor and comprising retail, office and a mixture of commercial and residential uppers, residential uses. whilst Winslow Road and the surrounding streets predominately comprise 2-3 storey • Proposed new-build development residential terraces. Frank Banfield Park is extending to approximately 3,369 situated directly to the west and Charing Cross Hospital is situated 100m to the south of the sqm (36,250 sq ft) GIA. site. St George’s development known as Fulham • Full planning permission for: Reach is located to the west of Frank Branfield Park with the River Thames beyond. • 32 x private and 2 x intermediate The retail offering on Fulham Palace Road is residential units. largely made up of independent shops, bars and restaurants, whilst a wider range of amenities • 2 x retail units. and retailers is found in central Hammersmith, • 6 basement car parking spaces. located approximately 0.55 km (0.3 miles) to the north of the site. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

The Bishop of London, Colonialism and Transatlantic Slavery

The Bishop of London, colonialism and transatlantic slavery: Research brief for a temporary exhibition, spring 2022 and information to input into permanent displays Introduction Fulham Palace is one of the earliest and most intriguing historic powerhouses situated alongside the Thames and the last one to be fully restored. It dates back to 704AD and for over thirteen centuries was owned by the Bishop of London. The Palace site is of exceptional archaeological interest and has been a scheduled monument since 1976. The buildings are listed as Grade I and II. The 13 acres of botanical gardens, with plant specimens introduced here from all over the world in the late 17th century, are Grade II* listed. Fulham Palace Trust has run the site since 2011. We are restoring it to its former glory so that we can fulfil our vision to engage people of all ages and from all walks of life with the many benefits the Palace and gardens have to offer. Our site-wide interpretation, inspired learning and engagement programmes, and richly-textured exhibitions reveal insights, through the individual stories of the Bishops of London, into over 1,300 years of English history. In 2019 we completed a £3.8m capital project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, to restore and renew the historic house and garden. The Trust opens the Palace and gardens seven days a week free of charge. In 2019/20 we welcomed 340,000 visitors. We manage a museum, café, an award-winning schools programme (engaging over 5,640 pupils annually) and we stage a wide range of cultural events. -

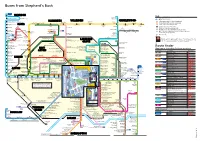

Buses from Sherpherd's Bush

UXBRIDGE HARLESDEN WILLESDEN CRICKLEWOOD HAYES LADBROKE GROVE EAST ACTON EALING ACTON TURNHAM GREEN Buses from Shepherd’s Bush HOUNSLOW BARNES 607 N207 Isleworth Brentford Gunnersbury Uxbridge UXBRIDGE Busch Corner Half Acre 316 Key Uxbridge Civic Centre Uxbridge Park Road Cricklewood 49 Day buses in black Bus Garage WILLESDEN CRICKLEWOOD N207 Night buses in blue HARLESDEN O Connections with London Underground Hillingdon Road The Greenway Harlesden Willesden Cricklewood — Central Middlesex Hospital Jubilee Clock Bus Garage Broadway ChildÕs Hill o Connections with London Overground 260 Hillingdon Lees Road HAYES Craven Park Willesden Cricklewood Golders R Connections with National Rail 228 Harlesden Green Kilburn Green B Connections with river boats South College Park Hayes End M Greenford South Early mornings and evenings only Willesden Junction Brondesbury Perivale Hampstead Chalk Farm G Daytimes only when Wetlands Centre is open Uxbridge 24 hour 31 24 hour 220 service County Court Greenford Park Royal 72 service 283 Swiss Cottage Camden Town L Not served weekday morning and evening peak hours Red Lion Hanger East Acton Lane ASDA Kilburn or Saturday shopping hours ROEHAMPTON Hayes Grapes Industrial Estate Scrubs Lane High Road DormerÕs Mitre Bridge N Limited stop Wells Lane Southall Ruislip Kilburn Park Trinity Road Lady Margaret Park Road s Road Royal Old Oak Common Lane QueenÕs Park The Fairway LADBROKE 95 Scrubs Lane 207 Southall Town Hall North Acton Mitre Way/Wormwood Scrubs 228 Southall Gypsy Corner GROVE Chippenham Road Police -

Proposal for Oak Processionary Moth Rapid Reaction Response Prepared by Forest Research on Behalf of the Forestry Commission’S Plant Health Service

Proposal for Oak Processionary Moth Rapid Reaction response prepared by Forest Research on behalf of the Forestry Commission’s Plant Health Service Introduction The finding of Oak Processionary Moth, Thaumetopoea processionea, in London during 2006 has resulted in considerable press and local authority interest in the threat posed by this moth. This threat encompasses both phytosanitary (the moth is very damaging to a range of oak species) and public health (the larvae possess highly irritating hairs) elements. This proposal does not directly address the public health issue as this is a matter outwith the competence of the Forestry Commission. To date, the responses to finding the moth have been fragmented and lack a coherent structure or overall co-ordinating body. Efforts to either manage the moth or to carry out surveys to determine the extent of the infestations have been very local and uncoordinated within London: • local authority surveys and application of control measures by Richmond Borough; • surveys and local control by Thames Water; • surveys and local control by Kew Gardens authorities; • surveys and local control by the highway authorities responsible for the A40 into London; • surveys and local control by Railtrack; • assessment of possible clustering of skin irritation complaints by local health authorities in London. Meetings have been held with some of the key players, including FR, Kew Gardens, local authorities (Acton, Richmond), local authority health officials, Defra PHSI and with an entomologist contracted to Richmond Borough Council. Arising from a meeting held in November 2006, a Tree Health Forum was organised and took place at Kew on 18 May. -

Office Suite 1 Fulham Palace Bishops Avenue, Fulham, London SW6 6EA Boston Gilmore LLP 020 7603 1616

Office Suite 1 Fulham Palace Bishops Avenue, Fulham, London SW6 6EA Boston Gilmore LLP www.bostongilmore.com 020 7603 1616 Private redecorated office suite Mainly first floor c.1,872 sq ft (174 sq m) approx HOUSE AND GARDEN BACKGROUND The historic house and garden of the Bishop of London since 704, now open to all to discover over 1300 years of British history in the heart of London. For centuries, this Grade I Listed building situated in extensive grounds by the River Thames was the country residence of the Bishops of London. Visitors to Fulham Palace have a wealth of things to see and do from exploring the museum that charts the Palace’s eventful history to having lunch in the Drawing Room restaurant that looks out onto the beautiful gardens. Fulham Palace garden is protected as an important historic landscape. Once enclosed by the longest moat in England, 13 acres remain of the original 36. The surviving layout is mainly 19th century with an earlier Walled Garden and some 18th century landscaping. www.fulhampalace.org LOCATION Fulham Palace and its grounds enjoy a stunning setting alongside Bishops Park on the banks of the River Thames. Bishops Avenue provides vehicular access, which leads to Fulham Palace Road, close to the junction with Fulham High Street and New Kings Road. Alternatively, an attractive riverside walk runs through Bishops Park to Putney Bridge. Putney Bridge Underground Station (District Line) is easily accessible and there are a number of bus routes from Hammersmith and Fulham Broadway. Fulham Palace Road provides convenient access north to Hammersmith Broadway connecting to the M4, and south over the river connecting to the A3/M3. -

2003 No 1 March.Pdf

WEST MIDDLESEX FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Executive Committee Chairman Robin Purr [email protected] Vice Chairman Mrs Sue Willard 11 Broad Walk, Heston, Middlesex TW5 9AA Secretary [email protected] Treasurer Paul Kershaw 241 Waldegrave Road, Twickenham TW1 4SY [email protected] Membership Secretary Mrs Bridget Purr 9 Plevna Road, Hampton Middlesex TW18 1EF [email protected] Editor Mrs Yvonne Masson 65 St Margaret’s Grove, East Twickenham Middlesex TW1 1JF [email protected] Publicity Officer Ted Dunstall 43 Elers Road, Ealing, London W13 9QB Committee Members Richard Chapman Janice Kershaw Margaret Harnden Lewis Orton Patrick Harnden Programme Secretary Mrs Antonia Davis 20 Evergreen Way, Hayes, Middlesex Society Web site http://www.west-middlesex-fhs.org.uk/ Subscriptions All Categories: £9.00 per annum Subscription year l January to 31 December Examiners Wendy Mott and Muriel Sprott In all correspondence please mark your envelope WMFHS in the upper left-hand corner; if a reply is needed, a SAE/IRCs must be enclosed. Members are asked to note that receipts are only sent by request, if return postage is included. Published by West Middlesex Family History Society Registered Charity No. 291906 WEST MIDDLESEX FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL Volume 21 Number 1 March 2003 Contents Future Meetings …………………………………………….. 2 News Roundup ……………………………………………... 3 The Riverside Village of Isleworth …………………………. 8 A London Childhood ……………………………………….. 14 Help! ………………………………………………………… 18 Computerising the West Middlesex Strays Index …………... 19 Bookshelf …………………………………………………… 22 Network 11 Tape Library …………………………………… 24 More . Servants in the Census ……………………………. 26 Society Publications on Microfiche ………………………… 28 Past Meetings ………………………………………………. -

2006 No 1 March.Pdf

WEST MIDDLESEX FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Executive Committee Chairman Mrs Yvonne Masson [email protected] Vice Chairman Jim Devine Secretary Tony Simpson 32 The Avenue, Bedford Park, Chiswick W4 1HT [email protected] Treasurer Paul Kershaw 241 Waldegrave Road, Twickenham TW1 4SY [email protected] Membership Secretary Mrs June Watkins 22 Chalmers Road, Ashford, Middlesex TW15 1DT [email protected] Editor Mrs Pam Smith 23 Worple Road, Ashford, Middlesex TW15 1DT [email protected] Committee Members Mavis Burton Kay Dudman Richard Chapman Patrick Harnden Mike Cordery Maggie Mold Programme Secretary Mrs. Maggie Mold 48 Darby Crescent, Sunbury-on-Thames Middlesex TW16 5LA Society Web site http://www.west-middlesex-fhs.org.uk/ Subscriptions All Categories: £10.00 per annum Subscription year l January to 31 December Examiners Chris Hern and Muriel Sprott In all correspondence please mark your envelope WMFHS in the upper left-hand corner; if a reply is needed, a SAE/IRCs must be enclosed. Members are asked to note that receipts are only sent by request, if return postage is included. Published by West Middlesex Family History Society Registered Charity No. 291906 WEST MIDDLESEX FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL Volume 24 Number 1 March 2006 Contents Future meetings …………………………………………….. 2 News Roundup ……………………………………………... 3 The Story of Greenwich ……………………………………. 6 Surnames on the Internet …………………………………… 7 Christmas Past and Present ………………………………… 8 The Rural Past ……………………………………………… 10 Tales from the Harlington Parish Registers ………………... 11 Certificate Courier Service …………………………………. 13 A Very Unconventional Great Aunt ……………………….. 14 Hayes Middlesex …………………………………………… 19 Enclosure in the 19th Century (Part 2) ……………………..