PROOF Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Evanovich Janet Evanovich Janet Evanovich Why Not Try: Why Not Try: Why Not Try

If you like Reading If you like Reading If you like Reading Janet Evanovich Janet Evanovich Janet Evanovich Why Not Try: Why Not Try: Why Not Try: Sheryl Anderson—Molly Forrester series Sheryl Anderson—Molly Forrester series Sheryl Anderson—Molly Forrester series Donna Andrews—Meg Langslow series Donna Andrews—Meg Langslow series Donna Andrews—Meg Langslow series Nancy Bartholomew—Sierra Lavotini series Nancy Bartholomew—Sierra Lavotini series Nancy Bartholomew—Sierra Lavotini series Anthony Bruno—Loretta Kovacs series Anthony Bruno—Loretta Kovacs series Anthony Bruno—Loretta Kovacs series Nancy Bush—Jane Kelly series Nancy Bush—Jane Kelly series Nancy Bush—Jane Kelly series Tori Carrington—Sofie Metropolis series Tori Carrington—Sofie Metropolis series Tori Carrington—Sofie Metropolis series Jill Churchill—Jane Jeffry series Jill Churchill—Jane Jeffry series Jill Churchill—Jane Jeffry series Jennifer Crusie Jennifer Crusie Jennifer Crusie Sparkle Hayter—Robin Hudson series Sparkle Hayter—Robin Hudson series Sparkle Hayter—Robin Hudson series Marne Davis Kellogg—Lilly Bennett series Marne Davis Kellogg—Lilly Bennett series Marne Davis Kellogg—Lilly Bennett series Harley Jane Kozak—Wollie Shelley series Harley Jane Kozak—Wollie Shelley series Harley Jane Kozak—Wollie Shelley series Charlotte MacLeod—Sarah Kelling series Charlotte MacLeod—Sarah Kelling series Charlotte MacLeod—Sarah Kelling series Sarah Strohmeyer—Bubbles Yablonsky series Sarah Strohmeyer—Bubbles Yablonsky series Sarah Strohmeyer—Bubbles Yablonsky series MENTOR PUBLIC LIBRARY MENTOR PUBLIC LIBRARY MENTOR PUBLIC LIBRARY www.mentorpl.org www.mentorpl.org www.mentorpl.org Janet Evanovich Janet Evanovich Janet Evanovich Checklist Checklist Checklist Stephanie Plum series: Jamie Swift & Stephanie Plum series: Jamie Swift & Stephanie Plum series: Jamie Swift & Max Holt series: Max Holt series: 1. -

Mayhem in the A.M. Book Discussion Group Henderson Library

Mayhem in the A.M. Book Discussion Group Henderson Library Presumed Innocent by Scott Turow (January 12, 2012) Rusty Sabich, a prosecuting attorney investigating the murder of Carolyn Polhemus, his former lover and a prominent member of his boss's staff, finds himself accused of the crime. The Ice Princess by Camilla Lackberg (February 9, 2012) After she returns to her hometown to learn that her friend, Alex, was found in an ice-cold bath with her wrists slashed, biographer Erica Falck researches her friend's past in hopes of writing a book and joins forces with Detective Patrik Hedstrom, who has his own suspicions about the case. Careless in Red by Elizabeth George (March 8, 2012) Scotland Yard's Thomas Lynley discovers the body of a young man who appears to have fallen to his death. The closest town, better known for its tourists and its surfing than its intrigue, seems an unlikely place for murder. However, it soon becomes apparent that a clever killer is indeed at work, and this time Lynley is not a detective but a witness and possibly a suspect. Killer Smile by Lisa Scottoline (April 12, 2012) When she receives personal threats and an associate is murdered, young lawyer Mary DiNunzio realizes that her latest case, involving a World War II internment camp suicide, may have deadly modern-day ties. The Janissary Tree by Jason Goodwin (May 10, 2012) When the Ottoman Empire of 1836 is shattered by a wave of political murders that threatens to upset the balance of power, Yashim, an intelligence agent and a eunuch, conducts an investigation into clues within the empire's once-elite military forces. -

Mysteries- Women Sleuths

MYSTERIES- WOMEN SLEUTHS SERIES China Bayless Mysteries Albert, Susan Wittig China Bayless is a Pecan Springs, Texas herb store owner (and former attorney). Herb lore and a portrait of a modern small town being reshaped by big city refugees are important features of this series. Thyme of death (1992) Witches' bane (1993) Hangman's root (1994) Rosemary remembered (1995) Rueful death (1996) Love lies bleeding (1997) Chile death (1998) Lavender lies (1999) Mistletoe man (2000) Bloodroot (2001) Indigo dying (2003) A dilly of a death (2004) Meg Langslow Andrews, Donna Andrews series provides plenty of laughs for readers who like their mysteries on the cozy side. Meg Langsdown is a sculptor by trade, but a PI by chance. “There's a smile on every page and at least one chuckle per chapter." -- Publishers Weekly Murder, with Peacocks (1999) Murder With Puffins (2000) Revenge of the Wrought Iron Flamingos (2001) Crouching Buzzard, Leaping Loon (2003) We'll always have parrots (2004) Turing Hopper Andrews, Donna Turning is a true original – a mainframe computer with a mind like Miss Marple and hardware that hides a spiciously human heart. You've Got Murder (2002) Click Here for Murder (2003) Carlotta Carlyle Barnes, Linda Six-foot-one red-head Carlotta Carlyle, former Boston cop and sometimes cabbie, sets herself up as an independent private investigator ready to deal with anything from lost pets to grand larceny. Trouble of fools (1987) Snake tattoo (1989) Coyote (1990) Steel guitar (1991) Snapshot (1993) Hardware (1995) Cold case (1997) Flashpoint (1999) Big dig (2002) Anna Pigeon Barr, Nevada All of Nevada Barr's novels center around Anna Pigeon, an independent, tough- talking, wine-drinking law enforcement park ranger. -

Taltp-Spring-2008-American-Romance

Teaching American Literature: A Journal of Theory and Practice Special Issue Spring/Summer 2008 Volume 2 Issue 2/3 Suzanne Brockmann (Anne Brock) (5 June 1960- Suzanne Brockmann, New York Times best-selling and RITA-award-winning author, pioneered and popularized military romances. Her well-researched, tightly-plotted, highly emotional, action-packed novels with their socially- and politically-pertinent messages have firmly entrenched the romance genre in the previously male-dominated world of the military thriller and expanded the reach and relevance of the romance genre far beyond its stereotypical boundaries. The Navy SEAL heroes of her Tall, Dark and Dangerous series published under the Silhouette Intimate Moments imprint and the heroes and even occasionally the heroines of her best-selling, mainstream Troubleshooter series who work for various military and counter-terrorism agencies have set the standards for military characters in the romance genre. In these two series, Brockmann combines romance, action, adventure, and mystery with frank, realistic examinations of contemporary issues such as terrorism, sexism, racial profiling, interracial relationships, divorce, rape, and homosexuality. Brockmann’s strong, emotional, and realistic heroes, her prolonged story arcs in which the heroes and heroines of future books are not only introduced but start their relationships with each other books before their own, and her innovative interactions with her readers, have made her a reader favorite. Suzanne was born in Englewood, New Jersey on 6 May, 1960 to Frederick J. Brockmann, a teacher and public education administrator, and Elise-Marie “Lee” Schriever Brockmann, an English teacher. Suzanne and her family, including one older sister, Carolee, born 28 January, 1958, lived in Pearl River, N.Y., Guilford, Conn., and Farmingdale, N.Y., following Fred Brockmann’s career as a Superintendent of Schools. -

PDF Download Hard Eight

HARD EIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Janet Evanovich | 352 pages | 03 Feb 2007 | St Martins Press | 9780312983864 | English | New York, United States Hard Eight PDF Book Alternate Versions. Stephanie realizes that Abruzzi is "conducting psychological warfare " against her, believing that she knows where Evelyn is. Writer: Paul Thomas Anderson. He wanted this thing in a certain way. Keno Bar Manager Kathleen Campbell William Parker. Rating Required Select Rating 1 star worst 2 stars 3 stars average 4 stars 5 stars best. Edit page. One of the best films of the year. He went on to earn further critical points for his role of the soldier sent to the front lines in Terrence Malick's war epic The Thin Red Line Get a sneak peek of the new version of this page. We accept the sincerity and altruistic motives of the aging loner he Philip Baker Hall portrays in this consciously spare Nevada-set sleeper. Hard Eight Gift Card. I had written a scene where two people talk about doing a scam. When John's and Clementine's honeymoon night leads to a disastrous hostage situation, Sydney takes care of it, as usual. Stephanie is asked by her parents' next-door neighbor, Mabel Markowitz, to find her granddaughter, Evelyn and great-granddaughter, Annie, who have disappeared. Play Episode Pause Episode. I was very happy that Lucy contacted me after I indicated that I needed help to add a message, as this was a gift card, being directly mailed to the recipient. But when slick casino pro Jimmy Jackson threatens to reveal a secret from Sydney's past that could destroy his relationship with the newlyweds, Sydney decides to hedge his bets and not leave anything to chance. -

If You Enjoy... the Stephanie Plum Books by Janet Evanovich

IF YOU ENJOY... THE STEPHANIE PLUM BOOKS BY JANET EVANOVICH Stephanie Plum is a bounty hunter with atti- tude. In Stephanie's opinion, toxic waste, rabid drivers, armed schizophrenics, and Au- gust heat, humidity, and hydrocarbons are all part of the great adventure of living in Jer- sey. She's a product of blue-collar Trenton, where houses are attached and narrow, cars are American, windows are clean, and dinner is served at six. Metro Girl by Janet Evanovich Size 12 is Not Fat by Meg Cabot When her wild and womanizing younger 28-year-old former pop star Heather Wells brother goes missing in southern Florida, has hit rock bottom, but when she finds a job Alexandra Barnaby endures humidity, sun- in a college dorm, things seem to start look burn, and bugs in her search for him along- up...at least until girls in the dorm begin to side Sam Hooker, who believes Barnaby's perish at an alarming rate. brother has stolen his boat. The Spellman Files by Lisa Lutz Bubbles Unbound by Sarah Strohmeyer Isabel Spellman may have a checkered past Against all odds, Bubbles Yablonsky has re- littered with romantic mistakes & creative turned to school, but while on her way to jour- vandalism; but the upshot is she's good at nalism school, she happens upon a crime her job as a licensed P.I. with her family's scene and finds herself drawn into a murder firm, Spellman Investigations. Invading peo- investigation. ple's privacy comes naturally to Izzy. In fact, it comes naturally to all the Spellmans… Crocodile on the Sandbank by Elizabeth The Miracle Strip by Nancy Bartholomew Peters The whip-smart Sierra Lavotini is the hottest After her father's death, thirty-two-year-old act on Panama City's strip scene. -

Tracing a Feminist Rewriting of the Detective Genre

ABSTRACT EMERSON, KRISTIN AMANDA. Women of Mystery and Romance: Tracing a Feminist Rewriting of the Detective Genre. (Under the direction of Leila May.) Many critics find that female characters in detective fiction are never entirely successful as either women or detectives. They argue that authors find it impossible to portray women properly in both roles—one persona always eclipses the other. The conflict is generally attributed to the traditionally “masculine” and conventional nature of the detective genre. This study proposes that the recent combination of detective fiction with the conventionally “feminine” genre of romance fiction offers hope for a feminist rewriting of the detective genre. A set of guidelines to subtly rescript detective fiction’s conventions is derived from suggestions by several critics, and is heavily influenced by typical elements of romance fiction. The usefulness of this framework in identifying the characteristics of more empowered and fully developed female detectives is tested by a close reading of three representative works from various points in the history of detective fiction. The three works, which include Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, Carolyn Keene’s Nancy Drew series, and Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum series, each incorporate a combination of romance and detective fiction and feature a female investigator. The framework proves useful in assessing the achievements and failures in the characterization of female detectives in these novels. It also offers guidelines that could be considered by authors of future detective works to rescript the most conservative elements of the detective fiction genre so that they no longer prevent the emergence of successful, empowered female detectives. -

Download Plum Boxed Set 3 Books 79 Seven up Hard Eight to the Nines Stephanie Plum Novels Pdf Ebook by Janet Evanovich

Download Plum Boxed Set 3 Books 79 Seven Up Hard Eight To the Nines Stephanie Plum Novels pdf ebook by Janet Evanovich You're readind a review Plum Boxed Set 3 Books 79 Seven Up Hard Eight To the Nines Stephanie Plum Novels book. To get able to download Plum Boxed Set 3 Books 79 Seven Up Hard Eight To the Nines Stephanie Plum Novels you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Book Details: Original title: Plum Boxed Set 3, Books 7-9 (Seven Up / Hard Eight / To the Nines) (Stephanie Plum Novels) Series: Stephanie Plum Novels Paperback: Publisher: St. Martins Press; Box edition (June 19, 2007) Language: English ISBN-10: 0312947453 ISBN-13: 978-0312947453 Product Dimensions:4.2 x 3 x 7.1 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 4651 kB Description: This boxed set contains three hilarious Stephanie Plum novels from Janet Evanovich: Seven Up, Hard Eight and To the Nines.Seven UpAll New Jersey bounty hunter Stephanie Plum has to do is bring in semi-retired bail jumper Eddie DeChooch. For an old man hes still got a knack for slipping out of sight--and raising hell. How else can Stephanie explain... Review: It is rare that I find a book that literally makes me laugh out loud when I read it. So far, Ive laughed out loud while reading each of the Stephanie Plum books. -

EVANOVICH, Janet

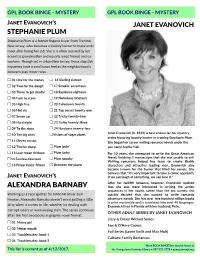

GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY JANET EVANOVICH’S JANET EVANOVICH STEPHANIE PLUM Stephanie Plum is a former lingerie buyer from Trenton, New Jersey, who becomes a bounty hunter to make ends meet after losing her job. She is is often assisted by her eccentric grandmother and equally inept friends and co- workers. Though set in urban New Jersey, these slapstick mysteries have a small town feel as the neighborhood's denizens play minor roles. 01 One for the money 16 Sizzling sixteen 02 Two for the dough 17 Smokin' seventeen 03 Three to get deadly 18 Explosive eighteen 04 Four to score 19 Notorious nineteen 05 High five 20 Takedown twenty 06 Hot six 21 Top secret twenty-one 07 Seven up 22 Tricky twenty-two 08 Hard eight 23 Turbo twenty-three 09 To the nines 24 Hardcore twenty-four Janet Evanovich (b. 1943) is best known for her mystery 10 Ten big ones Visions of sugar plums series featuring bounty-hunter-in-training Stephanie Plum. 11 Eleven on top She began her career writing romance novels under the 12 Twelve sharp Plum lovin' pen name Steffie Hall. 13 Lean mean thirteen Plum lucky For 10 years, she attempted to write the Great American 14 Fearless fourteen Plum spooky Novel, finishing 3 manuscripts that she was unable to sell. Writing romances helped her learn to create likable 15 Finger lickin' fifteen Between the plums characters and attractive leading men. Evanovich also became known for the humor that filled her novels. She believes that "it's very important to take a comic approach. -

Sustainable Shelves Q1 2021

Earley, Pete Serial killer whisperer $44.99 9781452604749; Prehistoric life / [authors, Douglas Palmer ... et al. consultants, Simon$40.00 Lamb ...9780756655730;"0756655730" et al.]. Eid, Alain. Minerals of the world / Alain Eid, Michel Viard [photographs] [translated$25.00 from the French]. 785808248 Tyson, Neil deGrasse. The Pluto files : the rise and fall of America's favorite planet / Neil deGrasse$23.95 Tyson.9780393065206 (hardcover);"0393065200 (hardcover)" Kirkland, Kyle. Force and motion / Kyle Kirkland. $35.00 0816061114 (acid-free paper);"9780816061112 (acid-free paper)" Lloyd, Seth, 1960- Programming the universe : a quantum computer scientist takes on the$26.00 cosmos1400040922 / Seth (alk. paper);"1400033861Lloyd. (pbk. : alk. paper)";"9781400040926" Susskind, Leonard. The theoretical minimum : what you need to know to start doing physics$26.99 / Leonard9780465028115 Susskind (hardcover) and George :;"046502811X" Hrabovsky. Kakalios, James, 1958- The physics of superheroes / James Kakalios. $26.00 1592401465;"9781592401468" Lincoln, Don, author. The Large Hadron Collider : the extraordinary story of the Higgs boson $29.95and other9781421413518 stuff (hardcoverthat :will alk. paper);"1421413515 blow your (hardcover mind : alk. paper)" / Don Lincoln. Hiltzik, Michael A., author. Big science : Ernest Lawrence and the invention that launched the military-industrial$30.00 9781451675757 complex hardcover;"1451675755 / Michael Hiltzik. hardcover" Stein, James D., 1941- Cosmic numbers : the numbers that define our universe / James D. Stein.$25.99 0465063799 (pbk.);"9780465021987 (hardback)";"0465021980 (hardback)";"9780465063796 (pbk.)" Wolfson, Richard. Simply Einstein : relativity demystified / Richard Wolfson. $24.95 0393051544 (hardcover) Jayawardhana, Ray. Neutrino hunters : the thrilling chase for a ghostly particle to unlock the$27.00 secrets9780374220631 of the universe (hbk.);"0374220638 / Ray Jayawardhana. -

Copper Cat Books 15 May 2019

Copper Cat Books 15 May 2019 Author Title Sub Title Genre Publication Date 1979 Chevrolet Wiring All Passenger Cars Automotive, 1979 Diagrams Reference 400 Notable Americans 1965 A compilation of the Historical 1914 messages and papers of the presidents A history of Palau Volume One Traditional Palau The First Anthropology, 1976 Europeans Regional A Treasure Chest of Children's A Sewing Book From the Ann Hobby 1982 Wear Person Collection A Visitor's Guide to Chucalissa Anthropology, Guidebooks, Native Americans Absolutely Effortless Feb 01, Prosperity - Book I 1998 Adamantine Threading tools Catalog No 4 Catalogs, Collecting/ Hobbies African Sculpture /The Art History/Study, 1970 Brooklyn museum Guidebooks Air Navigation AF Manual 51-40 Volume 1 & 2 Alamogordo Plus Twenty-Five the impact of atomic/energy Historical 1971 Years; on science, technology, and world politics. All 21 California Missions Travel U.S. El Camino Real, "The King's Highway" to See All the Missions All Segovia and province 1983 America's Test Kitchen The Tv Cookbooks 2013 Companion Cookbook 2014 America's Test Kitchen Tv the TV companion cookbook Cookbooks Companion Cookbook 2013 2013 The American Historical Vol 122 No 1 Feb 2017 Review The American Historical Vol 121 No 5 Dec 2016 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 2 Apr 2017 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 5 Dec 2017 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 4 Oct 2017 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 3 Jun 2017 Review Amgueddfa Summer/Autumn Bulletin of the National Archaeology 1972 1972 Museum of Wales Los Angeles County Street 1986 Guide & Directory.