Maryland Wetland Program Plan 2021 – 2025

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanticoke Currents Summer 2017

Nanticoke June | 2017 currents CONSERVING THE NATUR AL, CULTURAL, AND RECREATIONAL RESOURCES OF THE NANTICOKE RI VER Homeowners Workshops Golden Nanticoke Creek Freaks Workshop Learn about rain gardens, Was there a fungus among The NWA offers educators an rain barrels, pollinator- us? Find out what caused a opportunity to learn about friendly gardening practices, golden sheen on the our local waterways and lawn fertilization, converting Nanticoke in May. learn activities they can lawns to meadows, and conduct with their students See pages 2 & 3 . more. inside and outside. See page 6. See page 5. C+ Grade for the Nanticoke Report Card The Nanticoke’s grades slipped a bit this year. Increased rainfall and higher levels of phosphorus are damaging the waterways. Learn more about the issues and what you can do. See page 7. Unusual Golden Sheen on the Nanticoke River Photo Credit: Tom Darby Written by Mike Pretl & Judith Stribling May 22 dawned as a normal though periodically rainy day for NWA’s Creekwatchers. Every other Monday from late March through early November – rain or shine -- our trained volunteers visit 36 sites on the river and its major tributaries, from Delaware down to Nanticoke. These citizen scientists collect water samples and partner labs analyze for total nitrogen, total phosphorus, chlorophyll a, and bacteria. Creekwatchers also measure dissolved oxygen, salinity, water temperature, water clarity, and total water depth directly. Lastly, Creekwatchers note and record on data sheets the temperature and weather conditions as well as any unusual phenomenon of the water or its surrounding habitat. That morning, our river waters displayed nothing abnormal, only an occasional, slight film of brownish algae, to be expected in the spring months. -

Flood Insurance Study

FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY CECIL COUNTY, MARYLAND AND INCORPORATED AREAS Cecil County Community Community Name Number ↓ CECIL COUNTY (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) 240019 *CECILTON, TOWN OF 240020 CHARLESTOWN, TOWN OF 240021 CHESAPEAKE CITY, TOWN OF 240099 ELKTON, TOWN OF 240022 NORTH EAST, TOWN OF 240023 PERRYVILLE, TOWN OF 240024 PORT DEPOSIT, TOWN OF 240025 RISING SUN, TOWN OF 240158 *No Special Flood Hazard Areas Identified Revised: May 4, 2015 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 24015CV000B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of the FIS may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision (LOMR) process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: July 8, 2013 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: May 4, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Christina River Wetland Condition Report

Matthew A. Jennette Alison B. Rogerson Andrew M. Howard Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control Division of Watershed Stewardship 820 Silver Lake Blvd, Suite 220 Dover, DE 19904 LeeAnn Haaf Danielle Kreeger Angela Padeletti Kurt Cheng Jessie Buckner Partnership for the Delaware Estuary 110 South Poplar Street, Suite 202 Wilmington, DE 19801 The citation for this document is: Jennette, M.A., L. Haaf, A.B. Rogerson, A.M. Howard, D. Kreeger, A. Padeletti, K. Cheng, and J. Buckner. 2014. Condition of Wetlands in the Christiana River Watershed. Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Watershed Assessment and Management Section, Dover, DE and the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, Wilmington, DE. ii Christina River Wetland Condition ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided by EPA Region III Wetland Program Development Grant Assistance # CD-96312201-0, EPA National Estuary Program, the Delaware Department of Natural Resources, and the DuPont Clear into the Future program. Technical support and field research was made possible by the contributions of many individuals. Tracy Quirk and Melanie Mills from the Academy of Natural Science of Drexel University (ANS) for the collection and analysis of Site Specific data, and assistance with RAM data collection and analysis. Tom Kincaid and Tony Olsen with the EPA Office of Research and Development Lab, Corvallis, Oregon provided the data frame for field sampling and statistical weights for interpretation. Kristen Kyler and Rebecca Rothweiler participated in many field assessments under a myriad of conditions. Maggie Pletta and Michelle Lepori-Bui were helpful with revisions on drafts of the report, as well as producing the cover art for the final document. -

Nanticoke River Explorers Brochure

he Nanticoke River is the wetland functions. Both Maryland and Delaware have Submerged aquatic largest Chesapeake Bay identified the Nanticoke watershed as a priority area vegetation (SAV) tributary on the lower for protecting and enhancing natural resources for is considered an SCALE SEAFORD River Towns and Delmarva Peninsula, Nanticoke River recreation and conservation and recognize the need indicator species for 0 1 2 3 Watershed NANTICOKE RIVER The Tmeandering gently through marshland, to develop a greater sense of stewardship among water quality and 1 Points of Interest forests and farmland, on its 50 mile journey from southern the growing population. provides important miles Delaware to Tangier Sound in Maryland. Navigable beyond habitat for many Present Day307 Access and313 Information Seaford Boat Ramp SEAFORD, DE 1 Seaford, Delaware, the river has played an important role in animal species. Living Resources HURLOCK 20 Seaford was once part of Dorchester Nanticoke commerce and trade throughout its history, providing a critical Historically, there NANTICOKE WILDLIFE AREA, DELAWARE County in the Province of Maryland. First were well-established water route for early Native American tribes, and later for European The interaction between land and water that takes place in the This wildlife area surrounds historic Broad Creek called “Hooper’s Landing”, Seaford was settlers. The Nanticoke watershed encompasses approximately Nanticoke watershed has created diverse natural conditions and an SAV beds in the lower just South of Seaford, DE on the Nanticoke. Visitors laid out in 1799, and incorporated in 1865, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Atmospheric National Oceanic and Woodland just three days prior to the end of the Civil 725,000 acres, including over 50,000 acres of tidal wetlands. -

Fishing Regulations JANUARY - DECEMBER 2004

WEST VIRGINIA Fishing Regulations JANUARY - DECEMBER 2004 West Virginia Division of Natural Resources D I Investment in a Legacy --------------------------- S West Virginia’s anglers enjoy a rich sportfishing legacy and conservation ethic that is maintained T through their commitment to our state’s fishery resources. Recognizing this commitment, the R Division of Natural Resources endeavors to provide a variety of quality fishing opportunities to meet I increasing demands, while also conserving and protecting the state’s valuable aquatic resources. One way that DNR fulfills this part of its mission is through its fish hatchery programs. Many anglers are C aware of the successful trout stocking program and the seven coldwater hatcheries that support this T important fishery in West Virginia. The warmwater hatchery program, although a little less well known, is still very significant to West Virginia anglers. O West Virginia’s warmwater hatchery program has been instrumental in providing fishing opportunities F to anglers for more than 60 years. For most of that time, the Palestine State Fish Hatchery was the state’s primary facility dedicated to the production of warmwater fish. Millions of walleye, muskellunge, channel catfish, hybrid striped bass, saugeye, tiger musky, and largemouth F and smallmouth bass have been raised over the years at Palestine and stocked into streams, rivers, and lakes across the state. I A recent addition to the DNR’s warmwater hatchery program is the Apple Grove State Fish Hatchery in Mason County. Construction of the C hatchery was completed in 2003. It was a joint project of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the DNR as part of a mitigation agreement E for the modernization of the Robert C. -

A Summary of Peak Stages Discharges in Maryland, Delaware

I : ' '; Ji" ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY · Water Resources Division A SUMMARY OF PEAK STAGES AND DISCHARGES IN MARYLAND, DELAWARE, AND DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FOR FLOOD OF JUNE 1972 by Kenneth R. Taylor Open-File Report Parkville, Maryland 1972 A SUJ1D11ary of Peak Stages and Discharges in Maryland, Delaware, and District of Columbia for Flood of June 1972 by Kenneth R. Taylor • Intense rainfall associated with tropical storm Agnes caused devastating flooding in several states along the Atlantic Seaboard during late June 1972. Storm-related deaths were widespread from Florida to New York, and public and private property damage has been estllna.ted in the billions of dollars. The purpose of this report is to make available to the public as quickly as possible peak-stage and peak-discharge data for streams and rivers in Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. Detailed analyses of precipitation, flood damages, stage hydrographs, discharge hydrographs, and frequency relations will be presented in a subsequent report. Although the center of the storm passed just offshore from Maryland and Delaware, the most intense rainfall occurred in the Washington, D. c., area and in a band across the central part of Maryland (figure 1). Precipitation totals exceeding 10 inches during the June 21-23 period • were recorded in Baltimore, Carroll, Cecil, Frederick, Harford, Howard, Kent, Montgomery, and Prince Georges Counties, Md., and in the District of Columbia. Storm totals of more than 14 inches were recorded in Baltimore and Carroll Counties. At most stations more than 75 percent of the storm rainfall'occurred on the afternoon and night of June 21 and the morning of June 22 (figure 2). -

Defining the Nanticoke Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Indigenous Cultural Landscapes Study for the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail: Nanticoke River Watershed December 2013 Kristin M. Sullivan, M.A.A. - Co-Principal Investigator Erve Chambers, Ph.D. - Principal Investigator Ennis Barbery, M.A.A. - Research Assistant Prepared under cooperative agreement with The University of Maryland College Park, MD and The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, MD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Nanticoke River watershed indigenous cultural landscape study area is home to well over 100 sites, landscapes, and waterways meaningful to the history and present-day lives of the Nanticoke people. This report provides background and evidence for the inclusion of many of these locations within a high-probability indigenous cultural landscape boundary—a focus area provided to the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay and the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Advisory Council for the purposes of future conservation and interpretation as an indigenous cultural landscape, and to satisfy the Identification and Mapping portion of the Chesapeake Watershed Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Cooperative Agreement between the National Park Service and the University of Maryland, College Park. Herein we define indigenous cultural landscapes as areas that reflect “the contexts of the American Indian peoples in the Nanticoke River area and their interaction with the landscape.” The identification of indigenous cultural landscapes “ includes both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife therein associated with historic lifestyle and settlement patterns and exhibiting the cultural or esthetic values of American Indian peoples,” which fall under the purview of the National Park Service and its partner organizations for the purposes of conservation and development of recreation and interpretation (National Park Service 2010:4.22). -

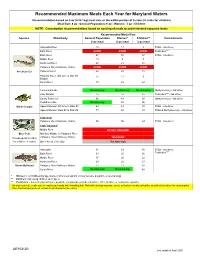

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Center for Excellence in Disabilities at West Virginia University, Robert C

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication was made possible by the support of the following organizations and individuals: Center for Excellence in Disabilities at West Virginia University, Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center West Virginia Assistive Technology System (WVATS) West Virginia Division of Natural Resources West Virginia Division of Tourism Partnerships in Assistive Technologies, Inc. (PATHS) Special thanks to Stephen K. Hardesty and Brittany Valdez for their enthusiasm while working on this Guide. 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 3 • How to Use This Guide ......................................... 4 • ADA Sites .............................................................. 5 • Types of Fish ......................................................... 7 • Traveling in West Virginia ...................................... 15 COUNTY INDEX .......................................................... 19 ACTIVITY LISTS • Public Access Sites ............................................... 43 • Lakes ..................................................................... 53 • Trout Fishing ......................................................... 61 • River Float Trips .................................................... 69 SITE INDEX ................................................................. 75 SITE DESCRIPTIONS .................................................. 83 APPENDICES A. Recreation Organizations ......................................207 B. Trout Stocking Schedule .......................................209 -

Watersheds.Pdf

Watershed Code Watershed Name 02130705 Aberdeen Proving Ground 02140205 Anacostia River 02140502 Antietam Creek 02130102 Assawoman Bay 02130703 Atkisson Reservoir 02130101 Atlantic Ocean 02130604 Back Creek 02130901 Back River 02130903 Baltimore Harbor 02130207 Big Annemessex River 02130606 Big Elk Creek 02130803 Bird River 02130902 Bodkin Creek 02130602 Bohemia River 02140104 Breton Bay 02131108 Brighton Dam 02120205 Broad Creek 02130701 Bush River 02130704 Bynum Run 02140207 Cabin John Creek 05020204 Casselman River 02140305 Catoctin Creek 02130106 Chincoteague Bay 02130607 Christina River 02050301 Conewago Creek 02140504 Conococheague Creek 02120204 Conowingo Dam Susq R 02130507 Corsica River 05020203 Deep Creek Lake 02120202 Deer Creek 02130204 Dividing Creek 02140304 Double Pipe Creek 02130501 Eastern Bay 02141002 Evitts Creek 02140511 Fifteen Mile Creek 02130307 Fishing Bay 02130609 Furnace Bay 02141004 Georges Creek 02140107 Gilbert Swamp 02130801 Gunpowder River 02130905 Gwynns Falls 02130401 Honga River 02130103 Isle of Wight Bay 02130904 Jones Falls 02130511 Kent Island Bay 02130504 Kent Narrows 02120201 L Susquehanna River 02130506 Langford Creek 02130907 Liberty Reservoir 02140506 Licking Creek 02130402 Little Choptank 02140505 Little Conococheague 02130605 Little Elk Creek 02130804 Little Gunpowder Falls 02131105 Little Patuxent River 02140509 Little Tonoloway Creek 05020202 Little Youghiogheny R 02130805 Loch Raven Reservoir 02139998 Lower Chesapeake Bay 02130505 Lower Chester River 02130403 Lower Choptank 02130601 Lower -

Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Connecting

CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH CHESAPEAKE NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL CONNECTING TRAILS EVALUATION STUDY 410 Severn Avenue, Suite 405 Annapolis, MD 21403 CONTENTS Acknowledgments 2 Executive Summary 3 Statement of Study Findings 5 Introduction 9 Research Team Reports 10 Anacostia River 11 Chester River 15 Choptank River 19 Susquehanna River 23 Upper James River 27 Upper Nanticoke River 30 Appendix: Research Teams’ Executive Summaries and Bibliographies 34 Anacostia River 34 Chester River 37 Choptank River 40 Susquehanna River 44 Upper James River 54 Upper Nanticoke River 56 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are truly thankful to the research and project team, led by John S. Salmon, for the months of dedicated research, mapping, and analysis that led to the production of this important study. In all, more than 35 pro- fessionals, including professors and students representing six universities, American Indian representatives, consultants, public agency representatives, and community leaders contributed to this report. Each person brought an extraordinary depth of knowledge, keen insight and a personal devotion to the project. We are especially grateful for the generous financial support that we received from the following private foundations, organizations and corporate partners: The Morris & Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, The Clay- ton Fund, Inc., Colcom Foundation, The Conservation Fund, Lockheed Martin, the Richard King Mellon Foundation, The Merrill Foundation, the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, the Rauch Foundation, The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, Verizon, Virginia Environmental Endowment and the Wallace Genetic Foundation. Without their support this project would simply not have been possible. Finally, we would like to extend a special thank you to the board of directors of the Chesapeake Conser- vancy, and to John Maounis, Superintendent of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Office, for their leadership and unwavering commitment to the Captain John Smith Chesapeake Trail.