Oyster Gardening We've Finally Got All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanticoke Currents Summer 2017

Nanticoke June | 2017 currents CONSERVING THE NATUR AL, CULTURAL, AND RECREATIONAL RESOURCES OF THE NANTICOKE RI VER Homeowners Workshops Golden Nanticoke Creek Freaks Workshop Learn about rain gardens, Was there a fungus among The NWA offers educators an rain barrels, pollinator- us? Find out what caused a opportunity to learn about friendly gardening practices, golden sheen on the our local waterways and lawn fertilization, converting Nanticoke in May. learn activities they can lawns to meadows, and conduct with their students See pages 2 & 3 . more. inside and outside. See page 6. See page 5. C+ Grade for the Nanticoke Report Card The Nanticoke’s grades slipped a bit this year. Increased rainfall and higher levels of phosphorus are damaging the waterways. Learn more about the issues and what you can do. See page 7. Unusual Golden Sheen on the Nanticoke River Photo Credit: Tom Darby Written by Mike Pretl & Judith Stribling May 22 dawned as a normal though periodically rainy day for NWA’s Creekwatchers. Every other Monday from late March through early November – rain or shine -- our trained volunteers visit 36 sites on the river and its major tributaries, from Delaware down to Nanticoke. These citizen scientists collect water samples and partner labs analyze for total nitrogen, total phosphorus, chlorophyll a, and bacteria. Creekwatchers also measure dissolved oxygen, salinity, water temperature, water clarity, and total water depth directly. Lastly, Creekwatchers note and record on data sheets the temperature and weather conditions as well as any unusual phenomenon of the water or its surrounding habitat. That morning, our river waters displayed nothing abnormal, only an occasional, slight film of brownish algae, to be expected in the spring months. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

The Nanticoke Heritage Byway Corridor Management Plan Acknowledgements

The Nanticoke Heritage Byway Corridor Management Plan Acknowledgements Steering Committee Donna Angel – Woodland Kevin Phillips - Bethel Linda Allen – Woodland Doug Marvil – Laurel Don Allen - Woodland Deborah Mitchell - Laurel Jim Blackwell – Seaford Gigi Windley – Phillips Farms Karin D’Armi Hunt – Seaford (Hearn’s Pond) Sterling Street – Nanticoke Indian Tribe Brenda Stover - Seaford (Hearn’s Pond) Dan Parsons - Sussex County Dave Hillegas – Bethel Ann Gravatt - Delaware Department of Transportation The Nanticoke Heritage Byway would like to thank the following for their continued dedication, assistance and guidance: Bethel Historic Society Laurel Redevelopment Corporation Community of Concord Nanticoke Indian Tribe Community of Woodland Previous Western Sussex Byway Committee Concord Historic Society Seaford Historic Society Delaware Department of Transportation Southern Delaware Tourism Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sussex County Council - Sponsor Control Dr. David Ames, University of Delaware – Center for Todd Lawson and Staff of Sussex County – IT, Mapping Historic Architecture and Design & Addressing, Engineering, Administration Federal Highway Administration Town of Bethel Greater Seaford Chamber of Commerce Town of Laurel HAPPEN group (Hearn’s Pond) Town of Seaford John Smith National Water Trail Woodland Church Laurel Chamber of Commerce Woodland Ferry Association Laurel Historic Society Woodland Historic Society State Government - former State Representative Cliff ord Lee (deceased), State Representative -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Bringing Kids Back to Nature by Theresa Gawlas Medoff

Child’s Play Bringing Kids Back to Nature By Theresa Gawlas Medoff 24 / O UTDOOR D ELAWARE Winter 2012 the Kaiser Family Foundation, today’s to connect with nature, and to gain school-age children spend 6.5 hours a day a sense of stewardship,” says Rachael with electronic media — and just minutes Phillos, nature center manager at Killens playing outdoors in unstructured activi- Pond State Park. ties. That’s a statistic that the folks at DN- The Educational Side REC’s Division of Parks and Recreation State park naturalists say that they are are acutely aware of, and one they are astounded sometimes by the naivety of trying their best to turn around. The some of the children who come to the Participants in Bellevue major part of the mission of Delaware parks on school fi eld trips. “They step off State Park’s Youth Fishing Tournament State Parks has always been to get people the bus and see more than four trees to- show off their catch. outside and into nature, says Ray Bivens, gether and think they are in the jungle,” DNREC operations, maintenance and Phillos says. programming section administrator. But “We often have kids who’ve never at a time when children are increasingly been in a forest before,” adds Angel nature deprived, our parks are doing Burns, naturalist at White Clay Creek more than ever to attract families by add- State Park. “They’re very concerned ing new programs, making people aware about going into the woods and want to of existing offerings, and increasing the know if there are bears out there.” accessibility of the parks. -

Nanticoke River Explorers Brochure

he Nanticoke River is the wetland functions. Both Maryland and Delaware have Submerged aquatic largest Chesapeake Bay identified the Nanticoke watershed as a priority area vegetation (SAV) tributary on the lower for protecting and enhancing natural resources for is considered an SCALE SEAFORD River Towns and Delmarva Peninsula, Nanticoke River recreation and conservation and recognize the need indicator species for 0 1 2 3 Watershed NANTICOKE RIVER The Tmeandering gently through marshland, to develop a greater sense of stewardship among water quality and 1 Points of Interest forests and farmland, on its 50 mile journey from southern the growing population. provides important miles Delaware to Tangier Sound in Maryland. Navigable beyond habitat for many Present Day307 Access and313 Information Seaford Boat Ramp SEAFORD, DE 1 Seaford, Delaware, the river has played an important role in animal species. Living Resources HURLOCK 20 Seaford was once part of Dorchester Nanticoke commerce and trade throughout its history, providing a critical Historically, there NANTICOKE WILDLIFE AREA, DELAWARE County in the Province of Maryland. First were well-established water route for early Native American tribes, and later for European The interaction between land and water that takes place in the This wildlife area surrounds historic Broad Creek called “Hooper’s Landing”, Seaford was settlers. The Nanticoke watershed encompasses approximately Nanticoke watershed has created diverse natural conditions and an SAV beds in the lower just South of Seaford, DE on the Nanticoke. Visitors laid out in 1799, and incorporated in 1865, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Atmospheric National Oceanic and Woodland just three days prior to the end of the Civil 725,000 acres, including over 50,000 acres of tidal wetlands. -

Parks & Recreation Council

Parks & Recreation Council LOCATION: Deerfield Gulf Club 507 Thompson Station Road Newark, DE 19711 Thursday, May 4, 2017 9:30 a.m. Council Members Ron Mears, Chairperson Ron Breeding, Vice Chairperson Joe Smack Clyde Shipman Edith Mahoney Isaac Daniels Jim White Greg Johnson Staff Ray Bivens, Director Lea Dulin Matt Ritter Matt Chesser Greg Abbott Jamie Wagner Vinny Porcellini I. Introductions/Announcements A. Chairman Ron Mears called the Council meeting to order at 9:45 a.m. B. Recognition of Esther Knotts as “Employee of the Year”, Council wished Esther congratulations on a job well done and recognition that is deserved. C. Mentioned hearing Jim White on the WDEL radio. II. Official Business/Council Activities A. Approval of Meeting Minutes Ron Mears asked for Council approval of the February 2nd meeting minutes. Ron Breeding made a motion to approve the minutes. Clyde Shipman seconded the motion. The motion carried unanimously. B. Council Member Reports: 1. Fort Delaware Society – Edith Mahoney reported. Kids Fest is June 10th. The Society is working with the Division to provide activities and games. All activities are free but the Society will be selling water and pretzels. Beginning Memorial Day they begin their Outreach program with Mount Salem Church and Cemetery. The Society needs to begin fundraising. Edith asked if there is any staff that work in the Division who could provide “pointers” on fundraising. Dogus prints they would like to save, need cameras in the library and AV room, and need to replace carriage wheels on the island. They would like to get a grant to help cover the costs. -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 Delaware - 10 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District KENT 2 - XXX A MCGINNIS POND ACCESS DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $50,250.00 C 12/20/1966 12/20/1968 1 3 - XXX A KILLENS POND STATE PARK DIV. OF PARKS & RECREATION $251,515.00 C 8/19/1967 9/1/1968 1 7 - XXX A MILFORD NECK DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $115,450.00 C 4/22/1967 4/22/1969 1 8 - XXX A ANDREWS LAKE ACCESS DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $10,562.50 C 4/20/1967 4/20/1969 1 10 - XXX A WOODLAND BEACH DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $11,000.00 C 4/3/1967 4/3/1969 1 11 - XXX A WOODLAND BEACH ACCESS DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $7,500.00 C 4/3/1967 4/3/1969 1 13 - XXX A LITTLE CREEK WILDLIFE AREA DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $33,000.00 C 5/25/1967 5/25/1969 1 14 - XXX A BLACKISTON WILDLIFE AREA DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $55,000.00 C 6/1/1967 6/1/1969 1 16 - XXX A BLACKISTON WILDLIFE AREA DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $101,250.00 C 6/2/1967 11/1/1967 1 20 - XXX A PETERSBURG-WRIGHT PROPERTY DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $17,750.00 C 12/19/1967 12/19/1969 1 25 - XXX A PETERSBURG-RASH DIV. -

Defining the Nanticoke Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Indigenous Cultural Landscapes Study for the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail: Nanticoke River Watershed December 2013 Kristin M. Sullivan, M.A.A. - Co-Principal Investigator Erve Chambers, Ph.D. - Principal Investigator Ennis Barbery, M.A.A. - Research Assistant Prepared under cooperative agreement with The University of Maryland College Park, MD and The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, MD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Nanticoke River watershed indigenous cultural landscape study area is home to well over 100 sites, landscapes, and waterways meaningful to the history and present-day lives of the Nanticoke people. This report provides background and evidence for the inclusion of many of these locations within a high-probability indigenous cultural landscape boundary—a focus area provided to the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay and the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Advisory Council for the purposes of future conservation and interpretation as an indigenous cultural landscape, and to satisfy the Identification and Mapping portion of the Chesapeake Watershed Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Cooperative Agreement between the National Park Service and the University of Maryland, College Park. Herein we define indigenous cultural landscapes as areas that reflect “the contexts of the American Indian peoples in the Nanticoke River area and their interaction with the landscape.” The identification of indigenous cultural landscapes “ includes both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife therein associated with historic lifestyle and settlement patterns and exhibiting the cultural or esthetic values of American Indian peoples,” which fall under the purview of the National Park Service and its partner organizations for the purposes of conservation and development of recreation and interpretation (National Park Service 2010:4.22). -

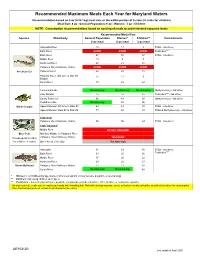

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Watersheds.Pdf

Watershed Code Watershed Name 02130705 Aberdeen Proving Ground 02140205 Anacostia River 02140502 Antietam Creek 02130102 Assawoman Bay 02130703 Atkisson Reservoir 02130101 Atlantic Ocean 02130604 Back Creek 02130901 Back River 02130903 Baltimore Harbor 02130207 Big Annemessex River 02130606 Big Elk Creek 02130803 Bird River 02130902 Bodkin Creek 02130602 Bohemia River 02140104 Breton Bay 02131108 Brighton Dam 02120205 Broad Creek 02130701 Bush River 02130704 Bynum Run 02140207 Cabin John Creek 05020204 Casselman River 02140305 Catoctin Creek 02130106 Chincoteague Bay 02130607 Christina River 02050301 Conewago Creek 02140504 Conococheague Creek 02120204 Conowingo Dam Susq R 02130507 Corsica River 05020203 Deep Creek Lake 02120202 Deer Creek 02130204 Dividing Creek 02140304 Double Pipe Creek 02130501 Eastern Bay 02141002 Evitts Creek 02140511 Fifteen Mile Creek 02130307 Fishing Bay 02130609 Furnace Bay 02141004 Georges Creek 02140107 Gilbert Swamp 02130801 Gunpowder River 02130905 Gwynns Falls 02130401 Honga River 02130103 Isle of Wight Bay 02130904 Jones Falls 02130511 Kent Island Bay 02130504 Kent Narrows 02120201 L Susquehanna River 02130506 Langford Creek 02130907 Liberty Reservoir 02140506 Licking Creek 02130402 Little Choptank 02140505 Little Conococheague 02130605 Little Elk Creek 02130804 Little Gunpowder Falls 02131105 Little Patuxent River 02140509 Little Tonoloway Creek 05020202 Little Youghiogheny R 02130805 Loch Raven Reservoir 02139998 Lower Chesapeake Bay 02130505 Lower Chester River 02130403 Lower Choptank 02130601 Lower -

Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Connecting

CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH CHESAPEAKE NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL CONNECTING TRAILS EVALUATION STUDY 410 Severn Avenue, Suite 405 Annapolis, MD 21403 CONTENTS Acknowledgments 2 Executive Summary 3 Statement of Study Findings 5 Introduction 9 Research Team Reports 10 Anacostia River 11 Chester River 15 Choptank River 19 Susquehanna River 23 Upper James River 27 Upper Nanticoke River 30 Appendix: Research Teams’ Executive Summaries and Bibliographies 34 Anacostia River 34 Chester River 37 Choptank River 40 Susquehanna River 44 Upper James River 54 Upper Nanticoke River 56 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are truly thankful to the research and project team, led by John S. Salmon, for the months of dedicated research, mapping, and analysis that led to the production of this important study. In all, more than 35 pro- fessionals, including professors and students representing six universities, American Indian representatives, consultants, public agency representatives, and community leaders contributed to this report. Each person brought an extraordinary depth of knowledge, keen insight and a personal devotion to the project. We are especially grateful for the generous financial support that we received from the following private foundations, organizations and corporate partners: The Morris & Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, The Clay- ton Fund, Inc., Colcom Foundation, The Conservation Fund, Lockheed Martin, the Richard King Mellon Foundation, The Merrill Foundation, the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, the Rauch Foundation, The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, Verizon, Virginia Environmental Endowment and the Wallace Genetic Foundation. Without their support this project would simply not have been possible. Finally, we would like to extend a special thank you to the board of directors of the Chesapeake Conser- vancy, and to John Maounis, Superintendent of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Office, for their leadership and unwavering commitment to the Captain John Smith Chesapeake Trail.