Arxiv:0709.0813V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring Semester 2021 (F21) 1 January 2021 Until 30 June 2021

Centro Astronomico´ Hispano-Aleman´ (CAHA) Call for proposals at the Calar Alto 2.2 & 3.5 meter telescopes Spring semester 2021 (F21) 1 January 2021 until 30 June 2021 DEADLINE: October 15th, 2020 23h59m59s (CEST) at the latest Earliest date for submission: September 17th, 2020 Calar Alto, September 16th, 2020. Contact: [email protected] Contents 1 Applications for observing time at Calar Alto4 1.1 General information...........................4 1.2 Spanish open time at the CAHA 2.2- and 3.5-m telescopes......4 1.3 Proposals from PIs in Europe but out of Spain.............4 1.4 Proposals from non-European PIs...................4 1.5 Visitor and service observing modes..................5 1.5.1 Visitor mode..........................5 1.5.2 Service mode..........................5 1.6 Ongoing surveys............................6 1.6.1 On the 3.5-m telescope.....................6 1.6.2 On the 2.2-m telescope.....................6 2 Important to notice6 2.1 No visits during the COVID-19 pandemic...............6 2.2 CAFE´ ..................................7 2.3 PANIC..................................7 3 How to write a proposal7 3.1 Calar Alto instrument pages......................8 3.1.1 Instruments offered on the 3.5-m telescope..........8 3.1.2 Instruments offered on the 2.2-m telescope..........8 3.2 Science categories of proposals.....................9 3.3 Types of proposal............................9 3.3.1 Re-submitted applications...................9 3.3.2 PhD thesis projects....................... 10 3.3.3 Long term or large projects................... 10 3.3.4 Testing new instruments.................... 10 3.3.5 Visitor instruments....................... 11 3.3.6 Multiple-instrument proposals................ -

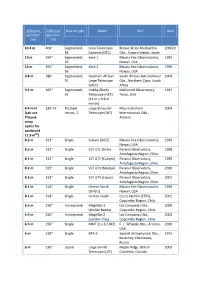

Effective Aperture 3.6–4.9 M) 4.7 M 186″ Segmented, MMT (6×1.8 M) F

Effective Effective Mirror type Name Site Built aperture aperture (m) (in) 10.4 m 409″ Segmented, Gran Telescopio Roque de los Muchachos 2006/9 36 Canarias (GTC) Obs., Canary Islands, Spain 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 1 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1993 36 Hawaii, USA 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 2 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1996 36 Hawaii, USA 9.8 m 386″ Segmented, Southern African South African Astronomical 2005 91 Large Telescope Obs., Northern Cape, South (SALT) Africa 9.2 m 362″ Segmented, Hobby-Eberly McDonald Observatory, 1997 91 Telescope (HET) Texas, USA (11 m × 9.8 m mirror) 8.4 m×2 330″×2 Multiple Large Binocular Mount Graham 2004 (can use mirror, 2 Telescope (LBT) Internationals Obs., Phased- Arizona array optics for combined 11.9 m[2]) 8.2 m 323″ Single Subaru (JNLT) Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 Hawaii, USA 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT1 (Antu) Paranal Observatory, 1998 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT2 (Kueyen) Paranal Observatory, 1999 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT3 (Melipal) Paranal Observatory, 2000 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT4 (Yepun) Paranal Observatory, 2001 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini North Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 (Gillett) Hawaii, USA 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini South Cerro Pachón (CTIO), 2001 Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 1 Las Campanas Obs., 2000 (Walter Baade) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 2 Las Campanas Obs., 2002 (Landon Clay) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Single MMT (1 x 6.5 M1) F. -

Distant Ekos: 2007 PS45, 2008 CS190 and 4 New Centaur/SDO Discoveries: 2008 FC76, 2004 VP112, 2005 UN524, 2008 CT190

Issue No. 58 May 2008 s DISTANT EKO di The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter r Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 10 Accepted Papers ........................ 3 Titles of 2 Submitted Papers ........................... 9 Conference Information .............................. ....9 Newsletter Information .............................. 10 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS There were 2 new TNO discoveries announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs: 2007 PS45, 2008 CS190 and 4 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2008 FC76, 2004 VP112, 2005 UN524, 2008 CT190 Objects recently assigned numbers: 1993 FW = (181708) 1998 WT31 = (181855) 1999 CG119 = (181868) 1999 CO153 = (181871) 1999 CV118 = (181867) 1999 HW11 = (181874) 1999 RD215 = (181902) 2000 YC2 = (182223) 2000 YU1 = (182222) 2001 KU76 = (182294) 2001 QW297 = (182397) 2002 FU6 = (182926) 2002 GJ32 = (182934) 2002 GZ31 = (182933) 2003 TG58 = (183595) 2004 DJ64 = (183963) 2004 DJ71 = (183964) 2004 PB112 = (184212) 2005 EO302 = (184314) Current number of TNOs: 1076 (including Pluto) Current number of Centaurs/SDOs: 227 Current number of Neptune Trojans: 6 Out of a total of 1309 objects: 557 have measurements from only one opposition 536 of those have had no measurements for more than a year 281 of those have arcs shorter than 10 days (for more details, see: http://www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews/objects/recov_stats.gif) 2 PAPERS ACCEPTED TO JOURNALS A Study of Photometric Variations on the Dwarf Planet (136199) Eris R. Duffard1, J.L. Ortiz1, P. Santos Sanz1, A. Mora2, P.J. Guti´errez1, N. Morales1, and D. Guirado1 1 Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, CSIC, Apt 3004, 18008 Granada, Spain 2 Universidad Aut´onoma de Madrid, Departamento de F´ısica Te´orica C-XI, 28049 Madrid, Spain Eris is the largest dwarf planet currently known in the solar system. -

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order Abe, H. 28 (8) 1993-1999 Bernstein, G. 1 1998 Abe, M. 1 (1) 1994 Bettelheim, E. 1 (1) 2000 Abraham, M. 3 (3) 1999 Bickel, W. 443 1995-2010 Aikman, G. C. L. 4 1994-1998 Biggs, J. 1 2001 Akiyama, M. 16 (10) 1989-1999 Bigourdan, G. 1 1894 Albitskij, V. A. 10 1923-1925 Billings, G. W. 6 1999 Aldering, G. 4 1982 Binzel, R. P. 3 1987-1990 Alikoski, H. 13 1938-1953 Birkle, K. 8 (8) 1989-1993 Allen, E. J. 1 2004 Birtwhistle, P. 56 2003-2009 Allen, L. 2 2004 Blasco, M. 5 (1) 1996-2000 Alu, J. 24 (13) 1987-1993 Block, A. 1 2000 Amburgey, L. L. 2 1997-2000 Boattini, A. 237 (224) 1977-2006 Andrews, A. D. 1 1965 Boehnhardt, H. 1 (1) 1993 Antal, M. 17 1971-1988 Boeker, A. 1 (1) 2002 Antolini, P. 4 (3) 1994-1996 Boeuf, M. 12 1998-2000 Antonini, P. 35 1997-1999 Boffin, H. M. J. 10 (2) 1999-2001 Aoki, M. 2 1996-1997 Bohrmann, A. 9 1936-1938 Apitzsch, R. 43 2004-2009 Boles, T. 1 2002 Arai, M. 45 (45) 1988-1991 Bonomi, R. 1 (1) 1995 Araki, H. 2 (2) 1994 Borgman, D. 1 (1) 2004 Arend, S. 51 1929-1961 B¨orngen, F. 535 (231) 1961-1995 Armstrong, C. 1 (1) 1997 Borrelly, A. 19 1866-1894 Armstrong, M. 2 (1) 1997-1998 Bourban, G. 1 (1) 2005 Asami, A. 7 1997-1999 Bourgeois, P. 1 1929 Asher, D. -

“Life in the Universe” Winners on La Silla and Paranal A

The Third NEON Observing School The Network of European Observatories in the North (NEON) is pleased to announce its third observing school, sponsored by the European Community, which will take place at Asiago Observatory (Italy) from September 9 to 22, 2002 The school is organised jointly and alternately by Asiago Observatory (Italy); Calar Alto Observatory (Germany-Spain) and Haute-Provence Observatory (France), with additional tutorial assistance from ESO. The purpose of the school is to provide opportunity to gain practical observational experience at the telescope, in observatories with state-of-the-art instrumentation. To this effect, the school proposes tutorial observations in small groups of 3 students, under the guidance of an experienced observer, centred around a small research project and going through all steps of a standard ob- serving programme. Introductory lectures are given by experts in the field. The list of topics includes telescope optics, photome- try, spectroscopy, data analysis, etc.… Special emphasis will be given this year on polarimetry. Additional topics cover VLT instru- mentation, virtual observatories, wide-field imaging, etc.… The school is open to students working on a PhD thesis in Astronomy, or young post-docs without previous observational ex- perience, and which are nationals of a member State or an associated State of the European Union. The working language is English. Up to fifteen participants will be selected by the organising committee and will have their travel and living expenses paid if they satisfy the EC rules (age limit of 35 years at the time of the Euro Summer School). Applicants are expected to fill in an application form (available on the Web site), with a CV and description of previous obser- vational experience, and to provide a letter of recommendation from a senior scientist familiar with the work of the applicant. -

![CASTLE: Performances and Science Cases Arxiv:2006.13956V1 [Astro-Ph.IM] 24 Jun 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9905/castle-performances-and-science-cases-arxiv-2006-13956v1-astro-ph-im-24-jun-2020-2009905.webp)

CASTLE: Performances and Science Cases Arxiv:2006.13956V1 [Astro-Ph.IM] 24 Jun 2020

CASTLE: performances and science cases S. Lombardo1, F. Prada2, E. Hugot1, S. Basa1, J. M. Bautista6, S. Boissier1, A. Boselli1, A. Bosma1, J. C. Cuillandre3, P. A. Duc4, M. Ferrari1, N. Grosso1, L. Izzo5, K. Joaquina1, Junais1, J. Koda6, A. Lamberts7, G. R. Lemaitre1, A. Longobardi1, D. Martínez-Delgado2, E. Muslimov1, J. L. Ortiz2, E. Perez2, D. Porquet1, B. Sicardy8, and P. Vola1 1Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS, CNES, LAM, Marseille, France. 2Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (CSIC), Glorieta de la Astronomía, E-18080 Granada, Spain. 3AIM, CEA, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cite, Observatoire de Paris, PSL University, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France. 4Observatoire Astronomique de Strasbourg, Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, 11 Rue de l’Université, F-67000 Strasbourg, France. 5DARK, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Lyngbyvej 2, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. 6Department of Physics and Astronomy, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-3800, USA. 7Université Cote d’Azur, Observatoire de la Cote d’Azur, CNRS, Laboratoire Lagrange, Laboratoire ARTEMIS, France. 8LESIA/Observatoire de Paris, univ. PSL, CNRS, Paris, France. June 26, 2020 Abstract We present here the Calar Alto Schmidt-Lemaitre Telescope (CASTLE) con- cept, a technology demonstrator for curved detectors, that will be installed at the Calar Alto Observatory (Spain). This telescope has a wide field of view (2◦.36×1◦.56) and a design, optimised to generate a Point Spread Function with very low level wings and reduced ghost features, which makes it considerably less susceptible to several systematic effects usually affecting similar systems. These characteristics are particularly suited to study the low surface brightness Universe. -

The 2017 May 20$^{\Rm Th} $ Stellar Occultation by the Elongated Centaur (95626) 2002 GZ $ {32} $

th The 2017 May 20 stellar occultation by 2002 GZ32 1 The 2017 May 20th stellar occultation by the elongated centaur (95626) 2002 GZ32 P. Santos-Sanz,1? J. L. Ortiz,1 B. Sicardy,2 G. Benedetti-Rossi,2;3;4 N. Morales,1 E. Fern´andez-Valenzuela,5 R. Duffard,1 R. Iglesias-Marzoa,6;7 J.L. Lamadrid,6 N. Ma´ıcas,6 L. P´erez,8 K. Gazeas,9 J.C. Guirado,10;11 V. Peris,10 F.J. Ballesteros,10 F. Organero,12 L. Ana-Hern´andez,12 F. Fonseca,12 A. Alvarez-Candal,3 Y. Jim´enez-Teja,3 M. Vara-Lubiano,1 F. Braga-Ribas,13;2;3;4 J.I.B. Camargo,3;4 J. Desmars,14;15 M. Assafin,4;16 R. Vieira-Martins,3;4 J. Alikakos,17 M. Boutet,18 M. Bretton,19 A. Carbognani,20 V. Charmandaris,21;22 F. Ciabattari,23 P. Delincak,24 A. Fuambuena Leiva,25 H. Gonz´alez,26 T. Haymes,27 S. Hellmich,28 J. Horbowicz,29 M. Jennings,30 B. Kattentidt,31 Cs. Kiss,32;33 R. Komˇz´ık,34 J. Lecacheux,2 A. Marciniak,29 S. Moindrot,35 S. Mottola,28 A. Pal,32 N. Paschalis,36 S. Pastor,37 C. Perello,38;39 T. Pribulla,34;40;41 C. Ratinaud,42 J.A. Reyes,37 J. Sanchez,18 C. Schnabel,38;39 A. Selva,38;39 F. Signoret,25 E. Sonbas,43 V. Al´ı-Lagoa44 1Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, IAA-CSIC, Glorieta de la Astronom´ıas/n, 18008 Granada, Spain 2LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, PSL Research University, CNRS, Sorbonne Universit´e, Univ. -

Appendix 1 897 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order

Appendix 1 897 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order Abe, H. 22 (7) 1993-1999 Bohrmann, A. 9 1936-1938 Abraham, M. 3 (3) 1999 Bonomi, R. 1 (1) 1995 Aikman, G. C. L. 3 1994-1997 B¨orngen, F. 437 (161) 1961-1995 Akiyama, M. 14 (10) 1989-1999 Borrelly, A. 19 1866-1894 Albitskij, V. A. 10 1923-1925 Bourgeois, P. 1 1929 Aldering, G. 3 1982 Bowell, E. 563 (6) 1977-1994 Alikoski, H. 13 1938-1953 Boyer, L. 40 1930-1952 Alu, J. 20 (11) 1987-1993 Brady, J. L. 1 1952 Amburgey, L. L. 1 1997 Brady, N. 1 2000 Andrews, A. D. 1 1965 Brady, S. 1 1999 Antal, M. 17 1971-1988 Brandeker, A. 1 2000 Antonini, P. 25 (1) 1996-1999 Brcic, V. 2 (2) 1995 Aoki, M. 1 1996 Broughton, J. 179 1997-2002 Arai, M. 43 (43) 1988-1991 Brown, J. A. 1 (1) 1990 Arend, S. 51 1929-1961 Brown, M. E. 1 (1) 2002 Armstrong, C. 1 (1) 1997 Broˇzek, L. 23 1979-1982 Armstrong, M. 2 (1) 1997-1998 Bruton, J. 1 1997 Asami, A. 5 1997-1999 Bruton, W. D. 2 (2) 1999-2000 Asher, D. J. 9 1994-1995 Bruwer, J. A. 4 1953-1970 Augustesen, K. 26 (26) 1982-1987 Buchar, E. 1 1925 Buie, M. W. 13 (1) 1997-2001 Baade, W. 10 1920-1949 Buil, C. 4 1997 Babiakov´a, U. 4 (4) 1998-2000 Burleigh, M. R. 1 (1) 1998 Bailey, S. I. 1 1902 Burnasheva, B. A. 13 1969-1971 Balam, D. -

Max-Planck-Institut Für Astronomie, Annual Report 1999

t für Astron titu om ns i -I e k H c e n id la e l P b - e x r a g M C a e i r n e t r o m l A A s t n ro a n m o le mi A co Hispano The Max Planck Society Max-Planck-Institut The Max Planck Society for the Promotion of Sciences was founded in 1948. In suc- cession to the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, which was founded in 1911, the Max Planck Society operates at present 78 Institutes and other facilities dedicated to basic and für Astronomie applied research. With an annual budget of around 2.3 billion DM in the year 2000, the Max Planck Society has about 11000 employees, of which one quarter are scien- tists. In addition, annually about 6900 junior and visiting scientists are working at the Institutes of the Max Planck Society. Heidelberg-Königstuhl The goal of the Max Planck Society is to promote centers of excellence at the fore- front of the international scientific research. To this end, the Institutes of the Society are equipped with adequate tools and put into the hands of outstanding scientists, who have a high degree of autonomy in their scientific work. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften Public Relations Office Annual Report 1999 Hofgartenstr. 8 D-80539 München Tel.: 0049-89-2108-1275 or -1277 Fax: 0049-89-2108-1207 Internet: http://www.mpg.de Cover Picture: In the hot intergalactic particle wind, dwarf galaxies loose their interstellar gas within few billion years. -

2008 OG19: a Highly Elongated Trans-Neptunian Object

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC MNRAS 456, 2354–2360 (2016) doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2739 2008 OG19: a highly elongated Trans-Neptunian object E. Fernandez-Valenzuela,´ ‹ J. L. Ortiz, R. Duffard, P. Santos-Sanz and N. Morales Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, IAA-CSIC, Glorieta de la Astronom´ıa s/n, 18008 Granada, Spain Accepted 2015 November 18. Received 2015 November 6; in original form 2015 July 16 ABSTRACT From two observing runs during the 2014 summer at the Calar Alto Observatory in Almer´ıa (Spain) and at the Sierra Nevada Observatory in Granada (Spain), we were able to derive CCD photometry of the Trans-Neptunian object 2008 OG19. We analysed the time series and obtained a double-peaked light curve with a peak-to-valley amplitude of 0.437 ± 0.011 mag and a rotational period of 8.727 ± 0.003 h. This implies that this object is very elongated, closely resembling the case of Varuna. The photometry also allowed us to obtain an absolute magnitude in the R band of 4.39 ± 0.07 mag. From this result, we estimated an equivalent +56 diameter of 2008 OG19 of 619−113 km using an average albedo for scattered disc objects. Finally, we interpreted the results under the assumption of hydrostatic equilibrium and found +42 −3 ± a lower limit for the density of 544−4 kg m . However, a more likely density is 609 4kg m−3 using an aspect angle of 60◦, which corresponds to the most likely configuration for the spin axis with respect to the observer assuming random orientations. -

Recent Grbs Observed with the 1.23 M CAHA Telescope and the Status of Its Upgrade

Recent GRBs observed with the 1.23m CAHA telescope and the status of its upgrade Javier Gorosabel1, Petr Kub´anek1,2, Martin Jel´ınek1, Alberto J. Castro-Tirado1, Antonio de Ugarte Postigo3, Sebasti´an Castillo Carri´on4, Sergey Guziy1, Ronan Cunniffe1, Matilde Fern´andez1, Nuria Hu´elamo5, V´ıctor Terr´on1, Nicol´as Morales1, Jos´eLuis Ortiz1, Stefano Mottola6, and Uri Carsenty6 1 Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa (IAA-CSIC), 18008 Granada, Spain. 2 Imaging Processing Laboratory (IPL), Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain. 3 INAF/Brera Astronomical Observatory, Via Bianchi 46, 23807, Merate(LC), Italy. 4 Universidad de M´alaga, M´alaga, Spain. 5 LAEX-CAB (INTA-CSIC); LAEFF, PO Box 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Ca˜nada, Madrid, Spain. 6 Institute of Planetary Research, DLR, Berlin, Germany. We report on optical observations of Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs) followed up by our collaboration with the 1.23m telescope located at the Calar Alto observatory. The 1.23m telescope is an old facility, currently undergoing up- grades to enable fully autonomous response to GRB alerts. We discuss the current status of the control system upgrade of the 1.23m telescope. The up- grade is being done by our group7 based on the Remote Telescope System, 2nd Version (RTS2), which controls the available instruments and interacts with the EPICS database of Calar Alto. Currently the telescope can run fully autonomously or under observer supervision using RTS2. The fast reaction re- sponse mode for GRB reaction (typically with response times below 3 minutes from the GRB onset) still needs some development and testing. -

Multiwavelength Observations of Fast Radio Bursts

universe Review Multiwavelength Observations of Fast Radio Bursts Luciano Nicastro 1,* , Cristiano Guidorzi 1,2,3 , Eliana Palazzi 1 , Luca Zampieri 4 , Massimo Turatto 4 and Angela Gardini 5 1 INAF—Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna, Via Piero Gobetti 93/3, I-40129 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (E.P.) 2 Department of Physics and Earth Science, University of Ferrara, Via Saragat 1, I-44122, Ferrara, Italy 3 INFN—Sezione di Ferrara, Via Saragat 1, I-44122 Ferrara, Italy 4 INAF—Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, I-35122 Padova, Italy; [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (M.T.) 5 Observatorio Astronómico Calar Alto s/n, Sierra de los Filabres, E-04550 Gergal, Almería, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-051-6398778 Abstract: The origin and phenomenology of the Fast Radio Burst (FRB) remains unknown despite more than a decade of efforts. Though several models have been proposed to explain the observed data, none is able to explain alone the variety of events so far recorded. The leading models consider magnetars as potential FRB sources. The recent detection of FRBs from the galactic magnetar SGR J1935+2154 seems to support them. Still, emission duration and energetic budget challenge all these models. Like for other classes of objects initially detected in a single band, it appeared clear that any solution to the FRB enigma could only come from a coordinated observational and theoretical effort in an as wide as possible energy band.